Beckett returned from Paris to Dublin in September 1930, and started work as a Lecturer in French at Trinity College. In certain respects, it was rather as though he had returned to England. He told MacGreevy that suburban Foxrock was capable of inducing an ‘ideally stupid’ mood in which he would read ‘the Strand magazine until it is time for tea and the Illustrated Morning News until it is time for bed’.1 He felt more and more at odds with Englishness in Ireland. He found himself increasingly estranged from Rudmose-Brown and his Anglo-Irish preoccupations and manners, partly because of the fuss about Le Kid. He was equally estranged from the academic scene and his own genteel background. Here his mother played the hapless and unwitting role of cultural antagonist. This led to rows, in particular, one over a piece of his writing which clearly grated on her Protestant nerve-ends. The young Beckett’s estrangement also expressed itself in a horror of his post. He repeatedly and famously said that ‘he could not bear teaching to others what he did not know himself’.2 This fastidious reluctance to dispense knowledge from on high had a historical dimension. What distressed Beckett was the assumption of the voice of Anglo-Irish superiority. Whilst Trinity still made it possible for him to speak in that voice, it was not one with which he felt able to identify.

This was by no means surprising. Ireland was moving in a direction that promised less and less scope to such voices. Between 1927 and 1932, two Irelands were locked in conflict, with one progressively superseding the other. Cosgrave and the ‘Free Staters’ were steadily losing power, whilst de Valera and Fianna Fáil were steadily gaining it. This meant a decisive shift towards a hardline Catholic, anti-British, agrarian nationalism. We get an exact sense of where this left Beckett if we compare his progress during these years to that of an older Anglo-Irish writer, W. B. Yeats. In the late 1920s, Yeats campaigned against the new legislation on censorship, divorce and the compulsory teaching of Gaelic. As Beckett’s essay ‘Censorship in the Saorstat’ (1935) makes abundantly clear, his sympathies were with this party (which consisted very largely of ‘a coterie of literary men’).3 The essay is withering about the Catholic Truth Society, the Irish as ‘a characteristic agricultural community’ and the pathetic ‘snuffles’ of ‘infant industries’ in Ireland (DI, p. 86). The sardonic last reference is to nationalist hopes for serious industrial development. These had by then effectively been dashed.

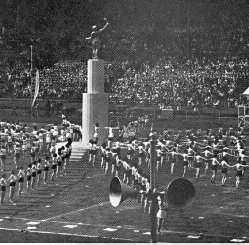

‘Ireland governed by Catholic ideas alone’: the Eucharistic Congress in O’Connell Street, Dublin, 1932.

After the 1932 elections, Ireland abolished the Anglo-Irish Treaty, gave itself a new constitution and cut all ties with the Commonwealth. In 1933, it abolished the Senate and the oath of allegiance. Thereafter, Yeats increasingly opposed ‘an Ireland governed by Catholic ideas and Catholic ideas alone’.4 Fearing for the place and role of Protestants in Ireland, he more and more withdrew his sympathies from Catholic nationalism. By 1934, however, he was also becoming anti-democratic and promoting a nostalgic concept of an aristocratic society governed by heroic figures. Beckett was not about to take this turn. In ‘Recent Irish Poetry’ (1934), whilst admitting that Yeats wove ‘the best embroideries’, he excoriated the ‘leading [Celtic] twilighters’ (DI, p. 71), their backward-looking antiquarianism and – derisively alluding to Yeats’s ‘Coole Park and Ballylee’ – their production of ‘segment after segment of cut-and-dried sanctity and loveliness’ (ibid.).5 He took issue with what he called ‘the entire Celtic drill of extraversion’ (DI, p. 73). Ireland had its scattered modern minds: MacGreevy, Denis Devlin, Brian Coffey. But the major cultural choices it offered were finally and equally cul-de-sacs.

Not surprisingly, therefore, in late 1931, Beckett gave up his post at Trinity. He fled to the Sinclairs in Germany, went back to Paris, lodged in the Gray’s Inn Road in London, then returned to Dublin, where he was soon rowing with his mother again. His life during this time was indecisive, aimless and spotted with misery, tension and disaster. In December 1931, he crashed a car with Ethna MacCarthy on board, hurting her more than he did himself. In May 1933, Peggy Sinclair died. Then, in June 1933, so did his father. Beckett had loved his father, not least for his decency and warm-heartedness. His death snapped already fraying ties. Beckett soon decamped to London, where he lived from 1933 to 1935.

Beckett’s London is a curious and striking thing. To some extent, as so often with writers and cities, one has to piece it together out of disparate bits. At the same time, it is important to draw out some of its more representative features. After 1922, southern Irish Protestants made up the great bulk of Irish emigrants. Irish Protestant culture had reached the end of a historical line. Protestants in Ireland now faced a dramatic loss of political and cultural power which spelt job discrimination and intolerance. Donald Akenson has shown that one-third of Southern Ireland’s Protestant population left between 1911 and 1926.6 Beckett grew up in an affluent but thinning Protestant suburb of Dublin. He could hardly have been unaware of the phenomenon of Protestant emigration. In 1933, he became part of the exodus specifically to Britain.

There was nothing at all strange about that. After 1922, Protestants were more likely to leave Ireland for Britain than anywhere else. Under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, the Irish retained their historical rights of free entry into the old colonial country without visa or work permit. Their destinations of choice, however, were no longer Scotland and the industrial north of England, as they had been in the nineteenth century, but one or other of the two locations in Murphy, London and the Home Counties. Not only were these the most affluent parts of England; the common perception of them was that they were bastions of conservative and middle-class English tradition, and were therefore the more likely to suit the refugees of a colon class. In the nineteenth century, Irish migrants to Britain had chiefly been poor and working-class. In the 1920s and ’30s, by contrast, ‘“a better class of emigrant” became more visible’,7 an emigrant of higher social standing and educational level.

If, however, Irish Protestant migrants arrived in the host country with expectations deriving from their social and cultural status in Ireland, these expectations were likely to be more or less rudely disappointed. Irish Protestants had long identified with English culture in Ireland. But that hardly meant that English culture itself was likely to welcome them with open arms or as kindred spirits. Protestants arriving in England who regarded themselves as British on arrival discovered that they were, after all, very Irish. Furthermore, in England, anyone Irish was likely to be viewed through the lens of time-honoured stereotypes, and there was a pervasive and casual contempt for ‘the Paddy’. According to Ultan Crowley, anti-Irish sentiment was particularly rife in England from 1922 to the 1940s, a legacy of the Anglo-Irish War and independence.8 For the Irish, Protestants and Catholics alike, their identity became a problematic matter as soon as they opened their mouths, and no new English identity was readily available to them. Such attitudes did not distinguish between Protestants and Catholics: the English remained largely immune to any plea for differentiation. To them, the Irish were all Murphies: that may partly be why Beckett gives his very uncommon protagonist such a very common Irish Catholic name.9

Beckett shared both aspects of the Protestant migrant’s experience of London. On the one hand, he had comparatively if modestly privileged connections. MacGreevy found a room for him in Paulton’s Square, off the King’s Road. This in itself is a less surprising setting for Beckett than it might seem: the 1931 census recorded heavy concentrations of Irish in Chelsea.10 At the same time, he was not far away from a respectable if not distinguished social scene. MacGreevy himself, for example, was lodging just round the corner with Hester Dowden, daughter of Edward Dowden, one-time secretary of the Irish Liberal Union, vice-president of the Irish Unionist Alliance and, by the time of his death in 1913, the most eminent of all the literary professors at Trinity. Beckett occasionally played piano duets with Hester in Cheyne Walk Gardens, amidst the teacups, Pekinese dogs and Siamese cats. The image is worth pondering. Equally, he was in London partly to benefit from the new middle-class panacea, psychoanalysis, for which his mother was paying. His analyst was Wilfred Bion, another idiosyncratic and intellectually fascinating gentleman with a colonial background and a good English education – though Bion also had a distinguished war record. They met at the Tavistock clinic, then in cultivated Bloomsbury. Their relationship became friendly and informal, and they spent time in each other’s company. Like Rudmose-Brown, Bion even had a nickname.

There was thus a sense in which Beckett’s social environment in London was not very far removed from the one he had enjoyed (or failed to enjoy) in Dublin. Yet a great deal of his experience in London also pushed him closer to the typical predicament of the migrant. On his trip to London in 1932, for example, he had run up against the problem of finding rented accommodation in insalubrious parts of the city. This could be bewildering for Irish migrants, not least because furnished rooms were not a standard feature of Dublin life. To some extent, the Beckett of 1932 also shared the migrant’s economic priorities and behaved accordingly, visiting agencies and, in his own phrase, ‘creeping and crawling’ for work with editors and publishers, notably resident Irishmen. He also repeatedly met with brusque rejection, or what he called ‘glib cockney regrets’.11

If London seemed unamiable (as it had to Joyce),12 Beckett responded in kind. He was unimpressed by historic London, finding the Tower uninteresting and the pompous nationalism of the interior of St Paul’s hideous. He invested Pope’s lines describing ‘London’s column’ – the Monument, in Epistle III of the ‘Moral Essays’ – as a tall bully lifting its head with a significance Pope had not intended. It was not the only time Beckett would associate London with power and intimidation. He hated the city, particularly its pervasive and automatic racism, and the condescension routinely meted out to him as an Irishman.13 Later in life, he called it ‘Muttonfatville’, and thought of it as singularly indifferent to human misery.14 Not surprisingly, the London Irish tended to close in on themselves, to become small communities within the larger one. These communities defined themselves in isolation from the English around them. Beckett’s friends in London, both male and female, were Irish.

As might be expected, in London Beckett was not only a solitary figure, but also given to nostalgia. He arrived in the metropolis in 1932, and quickly got involved in conversations about de Valera, who was in town at the same time.15 Throughout 1934, Ireland remained the focus of much of Beckett’s interest and attention.16 This, too, was quite typical of Irish migrants to Britain. For reasons both geographic and historical, they did not see themselves as making the same kind of decisive break as migrants to the USA or Australasia. They were much more likely to move back and forth between source and host cultures, finding plenty of opportunities ‘for continuing interactions with the homeland’.17 The tendency to gravitate back to Ireland, in spirit if not in person, was only exacerbated by the graceless prejudices so frequently in evidence around them.

Return in mind as he might, however, Beckett was not inclined to do it decisively or fully. His analysis with Bion was gradually allowing him to detach himself from his mother, and all the issues that were at stake in his quarrels with her. Interestingly, when his mother arrived for a visit in 1935, he was able to give her something that suited her but was remote from his England, a motorized tour of ‘pretty market-towns and cathedral cities’.18 But the process (of detachment) was as yet incomplete. This is expressed in the circumstances of composition of Beckett’s first major novel, Murphy. He began it in his lodgings in London, in August 1935. By Christmas of the same year, however, he was back in Dublin, where he caught pleurisy, was nursed by his mother and ended up fitting out a bedroom in Cooldrinagh as a study, in which he assembled his books from both Dublin and London and duly completed his novel.

If the Beckett of 1933 to 1935 remained suspended in a limbo that was cultural, intellectual and geographical all at once, this is exactly the condition dramatized in Murphy itself. It is an exercise in migrant writing. Murphy wants to be ‘sovereign and free’ (MU, p. 65), as did Ireland before 1922, though many Irish thought their country had properly been neither until 1933. Murphy, however, cannot identify with the versions of ‘freedom’ on offer in either Ireland or the Imperial capital. He therefore seeks his own peculiar form of Irish liberty ‘in the dark, in the will-lessness, [as] a mote in its absolute freedom’ (MU, p. 66). His pursuit of a distinctive freedom may ultimately be tragicomic. The novel nonetheless tells us a lot about what London meant to Beckett.

Murphy is a migrant. He has been in London for six or seven months, and Miss Counihan supposes him to be getting on with the migrant’s task, ‘sweating his soul out in the East End, so that I may have all the little luxuries to which I am accustomed’ (MU, p. 126). All the considerations involved in Murphy’s short-term future focus on London. Beckett endows him with some knowledge of Paris, but apparently not his own experience of having lived there. Murphy’s Parisian references are to the right bank (the Gare St-Lazare, Rue d’Amsterdam and the Boulevard de Clichy) rather than Beckett’s favourite rive gauche. The area around St-Lazare was even associated with London, not only because of the rail link, but via Huysmans, Mallarmé and Monet; though it seems probable that, given a taste which he shares with the Beckett of the period, Murphy is heading in the direction of the Place de Clichy for less cultivated reasons. As Henry Miller abundantly informs us, Clichy was well-known for its prostitutes.

Beckett also grants Murphy some of the reasons specifically for Protestant migration to England after 1922.19 Like Beckett in ‘Censorship in the Saorstaat’, Murphy is repeatedly scathing about the ‘new’ Ireland. He shares Neary’s dislike of falling ‘among Gaels’ (MU, p. 6). He is aided and abetted in his distaste by the novel itself, if in a succession of little touches, from the narrator’s disparagement of the ‘filthy censors’ (MU, p. 47) and alleged Irish nepotism (MU, p. 95) to the fact that Ramaswami Suk’s card distinguishes the Irish Free State from the Civilized World, to the image of Neary hilariously banging his head against Cuchulain’s ‘Red Branch bum’ in the General Post Office. This last image, of course, desecrates not just republican and nationalist but equally Revivalist ‘holy ground’ (MU, p. 28, 30), fusing two objects of Beckettian distaste, as does taking the name of Cathleen ni Houlihan in vain (in the reference to Dublin waitress Cathleen na Hennessey). Revivalism again becomes the principal target in Murphy’s memories of Irish writing as belches ‘wet and foul from the green old days’ (MU, p. 62), and his desire to have his ashes flushed down the lavatory at the Abbey Theatre, ‘if possible during the performance of a piece’ (MU, p. 151).

Oliver Sheppard’s 1911–12 statue of The Death of Cuchulain in the General Post Office, Dublin, ‘Red Branch bum’ invisible.

But if the novel makes Ireland seem backward and uninviting, it also makes London seem alienating. For Irish migrants, arriving in England spelled culture shock. London in particular was vast, its scale almost inconceivable to a Dubliner used to a manageable city that, in many ways, did not function or even look like a modern metropolis. From John O’Donoghue’s In A Strange Land to Paddy Fahey’s The Irish in London to Donal Foley’s Three Villages, Irish migrant memoirs return to certain themes: amazement at the vastness of London, including its miles of indifferent housing; the speed of life, the predominance of clock time, the sense of time as a commodity, sharply divided between work and leisure; the lack of any feeling of immediate community; the simple absence of the colour green. Most of these themes appear in Beckett’s novel, as in Murphy’s reference to ‘the sense of time as money … highly prized in business circles’ (MU, p. 43), or his evocation of his ‘medium-sized cage of north-western aspect commanding an unbroken view of medium-sized cages of southeastern aspect’ (MU, p. 5, 48). It is worth noting, too, that his ‘mew’ has been ‘condemned’ because it falls within a ‘clearance area’ (MU, p. 5, 15), reflecting the patterns of rapid construction and destruction of housing in the London of the period. This was yet another source of bewilderment to the migrant, whose disorientation was intensified by the sense that the metropolis was not only a Leviathan, but a protean one. It is therefore not surprising that the novel as a whole should have its occasional strains of pastoral wistfulness, as in Celia’s feeling for an Irish sky that is ‘cool, bright, full of movement’ and ‘anoint[s] the eyes’ (MU, p. 27).

Life in England was not invariably unrewarding. Murphy himself finds certain liberations in the migrant experience. Nonetheless, for the Irish migrant, the encounter with the host culture was likely to be problematic if not traumatic. Beckett’s novel underlines Murphy’s difficulty with questions of his position. In fact, independent Irishmen promptly lost their independent political status in England, since, in British eyes at least, Irish citizens were still viewed ‘as subjects’.20 At the level of daily life, this attitude was reproduced as the racism I noted earlier. Murphy runs right up against it, notably in the scene with the chandlers on the Gray’s Inn Road, where he is derided as not looking ‘rightly human’, that is, jeered at as the familiar type of the anthropoid Irishman from whom he has earlier sought to distinguish himself (MU, p. 47).

If Beckett gives him some of the migrant’s reasons for being in England, however, Murphy also stoutly resists the migrant’s logic. He is indifferent to Miss Counihan’s agenda. He plays the role of migrant with a mixture of intellectual bouffonnerie and ironical désinvolture, and thereby struggles to rise superior to its tribulations, oppressions and disempowerments. Indeed, in many ways, he is not only an untypical but an antitypical migrant. For he rejects the migrant’s internalized self-image, the former colonizer’s conception of the migrant as an eminently usable resource. He ostentatiously resists some of the preoccupations in the surrounding national culture, conceptions of life that the good, obedient migrant labourer was supposedly the better for absorbing. This is notably the case with health and diet. In 1930s England, health was becoming something of a national fixation. It even became an election issue. Every popular magazine had its regular feature on health. This was by no means simply a concern of the right’s. On the left, too, ‘there was a whole literature on nutrition, on the class-incidence of health’.21 Behind all this, of course, was an uneasy awareness that Germany was massively training young Germans in physical fitness: hence the British Physical Fitness Bill of 1936. Murphy, however, is categorically indifferent to this drive, and it is an object of parody in the well-known account of his lunch: ‘Murphy’s fourpenny lunch was a ritual vitiated by no base thoughts of nutrition…. “A cup of tea and a packet of assorted biscuits.” Twopence the tea, twopence the biscuits, a perfectly balanced meal’ (MU, p. 49).

‘British Physical Fitness’: the ‘Festival of Youth’ in Wembley Stadium, London, 1937.

Murphy also repudiates the Irish migrants’ habit of sticking together on the one hand, and oscillating between England and Ireland on the other. Wylie, Miss Counihan and Cooper both lead an existence split between Ireland and England, and cling together as a self-contained group. By contrast, Murphy has no interest at all in any expatriate Irish community and does not shuttle back and forth between cultures. Beckett’s ironical migrant novel even rethinks the geography of the imperial capital and redefines its spaces. In effect, it resists an official topography. Take Lincoln’s Inn Fields, for example. The London County Council had acquired it in 1895, and opened it up to the public. Lutyens had recently remodelled its most eminent building, Newcastle House. Murphy, however, strips it of its new appearance of modern benignity and reawakens its historical identity, a world of cozeners and cozened, of ‘crossbiting and conycatching and sacking and figging’, of ‘pillory and gallows’ (MU, p. 48).

This is very much in line with Beckett’s overriding conception of the brutality and rapacity of London. For in a novel which ends with the hero dying in a lunatic asylum, London is a city dominated by ‘the ruthless cunning of the sane’ (MU, p. 50). This was clearly how Beckett saw it. Lois Gordon emphasizes the importance of the effects of the Depression on the Britain that Beckett encountered when he arrived, in 1933.22 But Beckett’s England is hardly that of the Jarrow march. Indeed, there is no sense at all in Murphy of the politics of London in the 1930s, its strongly Labour culture, its Fascists and their attacks on Jews, its Communist groups, its conspicuous Left intellectuals.23 The Beckett of Murphy may seem strikingly melancholic. But he shares none of the specific melancholy that animates, say, the W. H. Auden of Look, Stranger (1936), with its haunting awareness of imminent historical catastrophe. In the 1930s, even the British Conservative Prime Minister-to-be Harold Macmillan thought that ‘the structure of capitalist society in its old form had broken down’.24 This does not appear to have occurred to Beckett. Indeed, he seems to present us with a very different if not actually opposed perception of economic circumstances.

However, by the years during which Beckett was actually living in London, 1933–5, the British economy was to some extent recovering from the Depression and even experiencing a miniboom. No doubt this was little felt in Jarrow. But London and the Home Counties were particularly undepressed. London supported ‘the country’s most affluent community’ and was ‘confident and expanding’ as never before, offering a dazzling choice of occupations and pastimes.25 It remained the financial capital of the world. This is the London Beckett sees; in other words, he sees the Imperial capital from the point of view of a colonial migrant. London is a ‘mercantile gehenna’ (MU, p. 26), the wealthy metropolitan centre of an imperial economic power. Its law is that of the ‘Quid pro quo!’ (MU, p. 5), the law of exchange, the market. Nor is ‘the ruthless cunning of the sane’ merely that of the plutomaniacs against whose deadly weaponry a ‘seedy solipsist’ is doomed to pit himself in vain (MU, p. 50). The primacy of cunning in the metropolis appears repeatedly in social relations both significant and trivial. Whether with Miss Carridge and her preoccupation with ‘domestic economy’ (MU, p. 43), the chandlers, Vera the waitress or Rosie Dew, again and again, Murphy’s relationships are repeatedly inflected by commerce and the economic interests of others.

This is above all what is at stake in his relationship with Celia. The issue on which the whole novel in fact hinges is whether, by insisting on the laws of exchange – love for financial security – Celia can convert the ironical migrant Murphy to the economism of the host country and the economic logic of the typical Irish migrant. Of course, she fails. Murphy is very interested in making love in England – his principal experience of migration as liberating – but remains entirely uninterested in making money there. True, this is not altogether remote from Irish migrant experience: one of the worries, for the Irish back home and, above all, the Irish Catholic church, was that Irishmen and women were likely to become much more relaxed about sexual morality as a result of living in decadent, modern, materialist England. At the same time, if the rot did set in, it was hardly as the result of a bohemian rejection of economic considerations. Its breeding-ground was much more likely to be (for example) the Irish dance-halls, to which hard-working Irish people in England increasingly turned for entertainment, companionship and consolation.

But Murphy unrelentingly refuses to adopt the economic rationale of the Irish migrant. His mind is never ‘on the correct cash-register lines’ (MU, p. 101). Perhaps his most crucial form of resistance lies in his struggle to overturn the structure of the English morality of work. Here, again, Murphy confronts and challenges stereotypes. English employers often thought of Irish employees as unusually hardworking. There were obvious reasons for this: economic migrancy meant that diligence was at a premium. Since migrant workers were frequently sending money home, it made sense for them to show an unusual degree of commitment to their jobs. Yet, contradictorily, some of the dominant English stereotypes were also of the Irish as slovenly and indolent. Even J. B. Priestley, writing in the 1930s, presented the Irish as not given to effort and natural slum-dwellers.26 Beckett and Murphy do not seek to challenge this stereotype. They rather seek to overturn the system of value that subtends both it and the English valuation of the industrious migrant labourer. It is not work, but indolence, the avoidance of work, that Murphy turns into an almost philosophical principle. In so doing, again, he challenges both the triumphant mercantilism of the old colonial power and the economic logic of Irish migration.

Finally, Murphy also redefines another important aspect of the Irish migrant’s historical experience: his or her relationship to the British asylum. For Irish migrants, life in England could also mean psychological distress. The admission rates of Irish-born patients into English asylums were exceptionally high. Liam Greenslade suggests that this was due to the problem of objecti-fication within the host culture. Since his national identity became a problematic object of attention as soon as he spoke, but no new English identity was immediately available to him, the Irish migrant endured a ‘pathological double-bind’ which prevented the formation of ‘a stable cultural identity’.27 For the most part, he was condemned to internalize the pathological projection of the colonizer, and therefore to be always at odds with his own image.

Murphy emphatically repudiates this projection. Irish patients in asylums had usually been working-class and Catholic, whilst the medical staff were predominantly English, middle-class and Protestant.28 Murphy goes voluntarily into an asylum, but on the side of the dominant power. He even refers to the inmates as another ‘race’ (MU, p. 97). Yet at the same time, he identifies with them and wishes to learn from them. He thus radically dissociates himself from the common position of the Irish migrant within the asylum, whilst also climbing down from his own relatively superior position. In the end, however, his efforts fail him. He seeks to subvert and ironize the role of the migrant from a migrant position. But the ironical space into which he moves finally turns out to be a dead-end. The experience of the ironical or antitypical migrant is just like the experience of the typical one, in being, in the end, an experience of definitive failure and loss.

Interestingly, in the years 1932–8, for Irishmen and women, the Depression was not in fact the principal economic concern. They were more preoccupied with the so-called Anglo-Irish ‘economic war’. This began with a British imposition of an import tax on Irish goods. De Valera and Fianna Fáil saw it as an attempt to browbeat Ireland on the Anglo-Irish Treaty by other than military or political means. It endangered the cause of Irish freedom, and had to be resisted at all costs. So Ireland imposed its own duties in turn. It claimed to be aspiring to (a Murphy-like) self-sufficiency. This cost it very dearly, where the British imposition cost Britain little or nothing. Indeed, Sean Lemass, Minister for Industry and Commerce, feared the return of famine conditions in Ireland.29 De Valera remained resolute, however, telling Ireland that it must accept deprivation as its lot if necessary, shoulder the burden of poverty, and agree to a diet of ‘frugal fare’.30

There is a sense in which one might think of Murphy as conducting his own private version of an economic war with England, on de Valera’s terms. Furthermore, he does so on the basis of unworldly terms that sound very Beckettian, but are also strikingly close to de Valera’s, not least in that Murphy accepts that ‘frugal fare’ is the necessary consequence of the struggle. By a strange and wonderfully paradoxical logic so characteristic of Beckett, the antitypical, deeply ironical migrant apparently so disdainful of Ireland, Irish independence and the Irish is finally identifiable, not only with the Irish migrant per se, but with the historical cause of Ireland itself.

Here we can finally come back to Yeats. If, in the 1930s, Yeats became ever more distant from Catholic Ireland, this did not mean that he gave up on his own nationalism or its anti-Imperial and anti-British dimensions. He remained proud of the Irish fight for freedom, not least what it achieved by means of the Statute of Westminster in 1931, which granted Ireland legislative sovereignty, and finally allowed it to declare itself a fully-fledged republic. He continued to attack British imperialist politics in the 1930s and was still inclined to see English culture as plagued by racism, hypocrisy, materialism and blind economism. ‘I hate certain characteristics of modern England’, he wrote.31 Beckett would have said the same. For all its paradoxical identification with Ireland, however, Murphy also remains marooned between two finally unacceptable cultures, just as Yeats was in old age, and Beckett was between 1933 and 1935. It soon became clear, however, that in Beckett’s case, unlike Yeats’s, other options were available.