By late 1936, it seemed as though Beckett’s limbo might swallow him up. He had completed Murphy, but both Chatto & Windus and Heinemann had quickly rejected it. He was thirty, and his mother was nagging him about his future career. He considered taking up menial employment in the family business, which his brother Frank was now running, and indulged in one or two extravagantly unrealistic fantasies, writing to Eisenstein to ask whether he might not train with him at the State Institute of Cinematography in Moscow, and even entertaining the bizarre idea of becoming an aviator. At the same time, when, by a piece of mild good fortune, he was offered the editorship of the Dublin Magazine, he turned it down, though he seemed well suited to it. He had a brief affair with an old childhood friend, Mary Manning, now married and Boston-based. By the time she went back home, he himself had decided to run from his predicament, leaving Dublin for Germany.

Beckett was by no means unfamiliar with German culture and the German language, not least because of his relationship with Peggy Sinclair. In 1928, he had travelled to Laxenburg, just south of Vienna, where Peggy was taking a course, and spent several weeks there. Whilst prosecuting their affair in 1928–9, he had also made several trips to Kassel, where the Sinclairs lived. Though he and Peggy had broken up, he had returned to see the Sinclairs in Kassel at Christmas in 1931, after his abrupt departure from Trinity College. All this had left its mark on Dream of Fair to Middling Women, which has claims to being Beckett’s most Germanic literary work. Plentiful ‘scraps of German’ – and of Germany – were clearly already ‘play[ing] in his mind’ (DFMW, p. 191). In 1936, however, instead of central Hesse, for the first time, Beckett headed for northern Germany, where he knew no one. He started in Hamburg on 2 October 1936. In the long run, the trip would take in Lubeck, Luneburg, Hanover, Brunswick, Hildesheim, Berlin, Halle, Weimar, Erfurt, Naumburg, Leipzig, Dresden, Pillnitz, Meissen, Freiberg, Bamberg, Wurzburg, Nuremberg, Regensburg and Munich. He also kept a diary.

By 1936, Germany had transformed itself. Hitler and the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (the NSDAP or Nazi party) had been in power since 1933. They had immediately introduced press censorship and suspended civil liberties. By the end of the year, they had opened the first concentration camp at Dachau, dissolved the labour unions and organized public burnings of un-German books. The new Germany was stridently aggressive. To many, it was clear in which direction events were leading. In 1935, Erich Ludendorff, former chief of German staff, ex-member of the Reichstag and one-time Hitler ally, turned Clausewitz on his head in Total War. The same year saw Germany walk out of the League of Nations and the Disarmament Conference and introduce universal military training, in defiance of the Treaty of Versailles. The drives at stake were inexorable. In the first instance, they were leading towards Kristallnacht, the Anschluss and the German entry into the Sudetenland, all of which took place in 1938. Beckett was certainly aware of them.

Police round up Communists and undesirable aliens in a Jewish quarter of Berlin in the early days of Nazi rule, 1933.

The order of the day was Gleichshaltung: everyone had to ‘fall into line’. Germany was caught up in an immense drive to uniformity, and turned punitively on citizens deemed to be racially, mentally or physically defective. The NSDAP brought in a Sterilization Law for the disabled as early as 1933, and founded the Racial Policy Office in 1934. On 15 September 1935, it introduced the Nuremberg Laws. The first law, the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour, prohibited marriages and extramarital sex between Germans and Jews, whilst the second, the Reich Citizenship Law, stripped persons not considered of German blood of their German citizenship. In any case, from 1933 onwards, the Nazis had been eliminating the left-wing press and steadily purging Jews, Communists and sometimes liberal opponents from the civil service, medical profession, universities, municipal authorities, churches and other professional, social and cultural organizations. Most ominously of all, by 1936, head of the ss Heinrich Himmler had full control of all German police.

Deirdre Bair suggests that Beckett’s encounter with Nazi Germany came as a shock to him. But he was not ignorant of the political situation.1 The diaries repeatedly indicate that he was either wearily familiar with Nazism beforehand, or very rapidly became so.2 He had no doubt learnt a lot from his earlier experience of Germany; from the Sinclairs themselves, who had returned to Ireland, partly because of William Sinclair’s Jewishness; and from newspapers, of which he was an avid reader. He got the Irish Times regularly from home, and read a number of different German newspapers and magazines – the Reichszeitung der Deutschen Erzieher, Frankfurter Zeitung, Hamburger Tageblatt, Berliner Tageblatt, Lustige Blätter, Dresdner Nachrichten, Leipziger Nachrichten, Dresdner Anzeiger, Bamberger Volksblatt and even the Nazi Volkischer Beobachter – at different times. Certainly, by late February 1937, he was stressing how often he had heard the Party line (GD, 24.2.37).

Nor did Beckett exactly ‘withdraw’ from what he saw of a monstrous society into art,3 though he certainly spent a very great deal of his trip steeping himself in painting and literature. At the same time, he emphatically declared his lack of interest in an art of explicit social or political criticism (GD, 28.12.36). To intellectuals hungry for a meditated Beckettian dissection of contemporary Germany, the diaries may seem frustrating. Beckett seldom comments at any length on the German scene.4 But anyone hopeful of finding an aesthetics thoughtfully and coherently elaborated in reaction to Germany will also be a little disappointed.5 The commentaries and theses on art and literature in the diaries appear here and there, in sporadic and disjointed fashion. The diaries themselves are concerned with a more particular and in some degree obscure experience than such terms suggest. Beckett’s responses to Nazi Germany were quite often visceral as much as intellectual, and frequently turbulent and intense, if in some ways contained.

Very occasionally, Beckett adopted some rather odd ideas about Germany. He agreed with Axel Kaun, for example, that Goebbels was really the malign genius of the Bewegung (the ‘Movement’), whilst Hitler and Goering were sentimentalists (GD, 19.1.37). But he was not at all ‘confused’ by Germany.6 He was hardly stupid. He was extremely conscious of the new German Lebensanschauung (view of life). He encountered it routinely: in waiters’ talk, for example (GD, 24.1.37, 28.1.37). He took the pulse of the new Germany through details. He was sensitive, for instance, to some of the more crassly masculine forms of the new culture: SA brass bands (GD, 14.2.37), groups of soldiers in public houses and churches (GD, 22.2.37, 4.3.37). He heard endless repetitions of the Hitlergruss (Heil Hitler!) in a Bierstube (GD, 5.12.36) and elsewhere. He listened to the carousings of the Hitlerjugend, just three weeks after membership of the organization had been made compulsory for all young German men (GD, 24.1.37).

He was not only aware of the general temper of what was going on in Germany. He knew or learnt a great deal about its particularities. He immediately understood that Germany was intent on war. He intuited this very soon after his arrival from a radio broadcast of Hitler and Goebbels haranguing the crowd at the inauguration of the Winterhilfswerk (GD, 6.10.36).7 The certainty of oncoming war hangs over the diaries like a pall: Beckett speculates, for example, on how war would be likely to affect a fellow-lodger in Hamburg (GD, 17.10.36). The goal of the Four-Year Plan, which was introduced at the annual NSDAP rally in 1936, and about which Beckett twice heard Hitler and Goering speaking on the radio (GD, 28.10.36, 30.1.37), was to prepare the German army and economy for war within a few years. The menace of Soviet Communism was the pretext for German rearmament. Beckett’s diaries note that Russian troops are supposedly massing on the Polish border (GD, 16.11.36) and remark, with varying degrees of irony, on the ‘threat from Moscow’ and film about it (GD, 11.10.36), and attacks on the Moscow ‘Judenklique’ (GD, 24.10.36). They also comment disapprovingly on anti-Bolshevist propaganda (GD, 1.11.36) and anti-Russian sentiments (GD, 7.11.36). Beckett even humorously claims to be keeping a list of items under the rubric ‘Moskau droht’ (‘Moscow is threatening’, GD, 1.11.36). In the Frankfurter Zeitung, he later read a justification of war as a catalytic accelerator of the historical process (GD, 14.3.37). That Germany signed the anti-Comintern Pact with Japan on 25 November – as Beckett knew from hearing Goebbels broadcasting on the subject on the radio (GD, 25.11.36) – must have made the ‘acceleration’ seem all the nearer.

Hitler had recently declared that the Germans required Lebensraum, more space, more sources of food and raw materials, and were aiming at Autarkie, economic self-sufficiency. Beckett heard some of the standard arguments for both: Germany lacked colonies, particularly after the Treaty of Versailles, as the other major European powers did not, and so could not feed its population; Germany needed to do without imports and establish a national currency independent of foreign ones (GD, 17.10.36). VoMi, the Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle, was founded in 1936 to coordinate policies towards German minorities outside Germany. Hitler had expanded the Weimar Republic’s definition of the Volksdeutsche to include German citizens of other countries as well as German residents in them. This would soon become a principal justification for invasions to the East. Beckett was aware of the theme, notably with regard to the racial composition of Czechoslovakia (GD, 19.1.37, 7.3.37).

Within three days of arriving in Hamburg, he was commenting ruefully on the Nazi purges of inconveniently nondescript humanity. Not a whore to be found on the Reeperbahn, he noted: they seemed to have been all locked up (GD, 5.10.36). The NSDAP had been interning ‘asocials’ or Gemeinschaftsunfähigen, those unfit for society, since 1933. They included beggars, vagrants, alcoholics and prostitutes. In 1936, they were particularly embarrassing. For 1936 saw that peculiarly grandiose celebration of Fähigkeit (capability), the Berlin Olympic Games. These ended just six weeks before Beckett arrived; he was unremittingly scornful of the values they represented, preferring ‘the fundamental unheroic’.8 His work would later defend and even revel in Unfähigkeit. The concept became key to his aesthetics, as for example in the famous discussion of ‘inability’, not being able, in Three Dialogues (DI, p. 145). The roots of Beckett’s feeling for incapacity were doubtless elsewhere. Nonetheless, his experience of Germany in1936–7 clearly provided a vital additional reason for his identification with hapless outsiders. Of the painters of the Hamburg Sezession, in whom he had a ‘special interest’ and whom he took to be ‘alert witnesses of Germany in 1936’,9 he was particularly drawn to Willem Grimm, because, in 1936, he appeared to be attracting so much personal abuse, and seemed verbummelt, dissolute, a man who was down on his luck (GD, 24–25.11.36).

Beckett knew about Nazi racial policies well before he reached Germany. It is clear from the diaries that, in Germany itself, he came to know about them in some detail. In 1933, Alfred Rosenberg had taken the Nordische Gesellschaft – the organization for German-Nordic cooperation – under Nazi protection, increasingly sweeping the Nordic peoples into a ‘greater German Reich’.10 On 13 September 1936, the NSDAP had announced the foundation of the Lebensborn agency to encourage young unmarried women to give birth to Nordic children. As George Orwell indicated on 17 October, by this time, the word ‘Nordic’ had a singular charge.11 Beckett’s dispassionate response, just ten days later, to a group of German-speaking Scandinavians at the Nordische Gesellschaft in Hamburg suggests a conscious distaste for the doctrine of Nordic racial superiority (GD, 27.10.36).

Above all, Beckett was extremely aware of the persecution of German Jews. He notes, for example, that art-historian Rosa Schapire could not publish or give public lectures because she was not of pure Aryan descent (GD, 15.11.36). He discovered that Gretchen Wohlwill, the Jewish ‘Mother’ of the Hamburg Sezession, was now regarded as an unsuitable custodian of German culture (GD, 21.11.36).12 He listened to stories about Jews (GD, 23.2.37) and ferocious anti-Semitic diatribes (GD, 22.2.37), heard Jews blamed for problems in trade (GD, 28.1.37), and saw photographers outside Jewish shops and ugly anti-Semitic slogans on walls (GD, 21.1.37, 16.2.37). Acquaintances openly expressed their hatred of Jews. In Berlin, for example, his landlord Kempt told him the history of his own personal anti-Semitism (GD, 6.1.37). Beckett knew the term Rassenschande, racial disgrace, knew what it meant in Hitler’s Germany – sex between Jews and non-Jews – and knew that the first Nuremberg Law forbade that non-Aryan households employ Aryan women under 45, for fear of it (GD, 24.11.36). The corollaries to the Reich Citizen Act of 14 November 1936 defined categories of Mischlinge, racial mixtures, and Beckett was aware of the issue of racial exclusivity and arguments made for it (GD, 29.3.37).

His responses to the monstrosities of Nazi Germany are various. For about two months, he thought of writing a work that might be ruefully appropriate to the Third Reich, what he referred to as his Journal of a Melancholic (GD, 31.10.36). No such work appears to have survived,13 but Beckett might have given the title to the diaries themselves. They are nothing if not a tale of protracted melancholy, as he himself was aware (GD, 18.10.36). Indeed, they are at times devoured by what Evelyne Grossman describes as a Beckettian ‘passion mélancolique’.14 As at other times in his life, however, Beckett’s melancholy did not preclude resistance. Indeed, the two went hand in hand. He illegally acquired Max Sauerlandt’s banned account of the art of the preceding thirty years. He got hold of Karl Heinemann’s German literary history precisely because it had appeared before the Machtübernahme (Nazi takeover).15 He was stiffly dismissive of historical narratives of the German nation (GD, 15.1.37). He was profoundly suspicious of anyone who appeared even faintly to believe in the Sonderweg, the special German way (ibid.). He was repelled by any conception of the uniqueness of the German Schicksal or fate, indeed, by German narratives as and of heroic journeys in general. This he made clear to Kaun on 15 January 1937:

I say I am not interested in a ‘unification’ of the historical chaos any more than I am in the ‘clarification’ of the individual chaos, + still less in the anthropomorphisation of the inhuman necessities that provoke the chaos. What I want is the straws, flotsam, etc., names, dates, births & deaths, because that is all I can know.16

Not the wave, but the corks upon it: after all, as he adds, drily, later in the diaries (GD, 20.1.37), the twentieth is the century of God’s aboulia, a pathological failure of divine will and powers of decisive action.

If the young Beckett’s nature included any will seriously to conform to iron norms, it was at best exiguous. He was ill-adapted to the culture of Gleichshaltung, and temperamentally at odds with it.17 This made for irreverence and disrespect. He suggested, for example, that the Nazis might create a cadre of HH, Hitlerhuren, Hitler Whores, to match the ss (GD, 6.2.37). He referred to Mein Kampf as Sein Krampf, and the Vierjahresplan as the Bierjahresplan.18 When he went to a talk by Werner Lorenz, ss Gruppen-and shortly to be Obergruppenführer, General of the Waffen-ss and police and, from January 1937, chief of VoMi, he gave the fascist salute with the wrong arm (GD, 11.10.36). The fact that he describes himself as partly saluting Horst Wessel makes it the more piquant. Wessel was the official martyr of the Nazi movement (killed by Communists after a dispute with his landlady). The Horst Wessel song had been the Nazi anthem since 1931. Wessel’s name had recently been in the news, because Hitler had commissioned the ship that bore it as a Schulschiff.19 Beckett clearly felt a particular distaste for Wessel (a maniacally violent creature, whose animality he deftly indicates, GD, 19.12.36). He remarks in Berlin that, ironically enough, Wessel was raised in Judenstrasse (GD, 18.12.36).

Beckett could not be wooed: urged by Claudia Asher – apparently Nazi-inclined and anti-Semitic20 – to surrender his Abstand (detachment) for the Abgrund (abyss), he doggedly replied that he intended to buy the complete works of Schopenhauer (GD, 24.10.36). He knew of the Nazi Kraft durch Freude division, which organized cultural and leisure activities for the working classes, and stated that he preferred his own KDF, Kaspar [sic] David Friedrich (GD, 1.11.36, 9.2.37; German graffiti artists still play with the initials today).21 He wilfully refused to associate the Verfassung der Ehe (marriage bond) with anything more than sex (GD, 1.11.36), which takes on a particular significance in the light of the Nuremberg Laws. In 1933, Hitler had declared Munich to be ‘the city of German art’.22 Beckett views fascist architecture like Paul Ludwig Troost’s monumental new Haus der deutschen Kunst in Munich with scrupulous disfavour. It lacks imagination, he declares, and smells of Furcht vor Schmuck, fear of ornament (GD, 10.3.37).

Otherwise, firstly: he walks. David Addyman has recently brilliantly argued that Beckett’s work is characterized both by its topophobia, its resistance to all thought of ‘emplacement’, and a sober recognition that one is never truly out of place.23 This might be the case with much of it. But it isn’t really the case with the German Diaries. In the Hamburg section in particular, but also elsewhere, Beckett is intent on noting down street names, place-names, names of buildings, usually without further comment. He tells us where he went, where he went next, where he went after that … One explanation, clearly, is that, contra Addyman in this case, he is concerned to feel at home in a new town.24 But this is to forget an obvious precursor. Beckett’s assemblages of names recall Joyce’s. Joyce, of course, famously declared that if Dublin were destroyed it could be rebuilt with Ulysses as guide. His art was, in this respect, a work of conservation or memorialization. So, too, in a world where, as he already knew, Hitler and Goebbels were heading for war, haphazardly, without Joyce’s sense of coherent purpose, Beckett recorded places simply as having been there.

Secondly: he talks. From the start of his trip, he showed himself to be quite unusually avid for conversation with comparative strangers. He was determined to find useful German conversation partners (GD, 13.10.36), paying for language with beer if necessary (GD, 2.11.36). But the German that Beckett heard in conversation was a particular German. Early on in the diaries, he speculated on the German translation of ‘bilge’ (a word he used in connection with Smyllie and Oliver St John Gogarty among others, GD, 1.11.36, 7.1.37). He quickly recalled one: Quatsch.25 It recurs throughout the diaries. He increasingly heard ordinary Germans’ ‘emissions’ (GD, 22.11.36) as a discourse, or a set of related discourses. These discourses were stuffed with contemporary German notions: the Führer, the Bewegung, Rassenschande, Blut und Boden (blood and soil). Furthermore, apparently more neutral words – Energie, Wollen (will), Ehre (honour), Helden (heroes), Verhetzung (instigation), Schwärmerei (enthusiasm), Reinheit (purity) – had taken on disquieting new implications.

Beckett genuinely listened to Nazi Germany. He listened attentively.26 He was acutely conscious of voices and what they could tell him about his circumstances. In Berlin, for example, he heard Kempt’s and others’ adoration of Hitler in their voices (GD, 19.1.37, 5.3.37). Individuals repeatedly spoke fervently of the Bewegung. He heard the effects of propaganda in others’ voices, whether it was for the new autobahns or the wonders of the Schorfheide (GD, 5.1.37; Goering owned a mansion there, and planned to establish it as a National Socialist nature reserve). But he also heard equivocation. Whilst the mass of German people had rallied behind Hitler well before 1936 – on 29 March of that year, 99 per cent of Germans voted for the Nazis – in practice, many people compromised, colluded, practised doublethink, adopted the role of the Mitläufer or fellow traveller. The historian Pierre Ayçoberry describes this as the period in which the German middle classes in particular took ‘Continue to function’ as their maxim.27 Beckett’s German milieu tended to be fairly bourgeois and respectable, notably in Hamburg, and, however fitfully, he was aware that others were sometimes playing a double game.

His response to this doubleness is striking. He repeatedly distinguishes people from their historically and culturally determined language, the discourses of the day in which they are caught up. Thus talking to a man called Power prompts him to observe that people’s relative likeability and the views they hold frequently have little to do with each other (GD, 16.11.36). Here and there, he adopts a practice of double notation. The Wirt he encounters at a Gasthaus on 16 February 1937, for example, spouts the usual rubbish; but he is also, Beckett adds, a nice man and a faintly touching figure. Ida Bienert recites the Nazi litany but is very amiable (GD, 11.2.37, 15.2.37). Decent individuals take up appalling positions (GD, 20.12.36). Of course, it is hard to know just where this kind of perception tips over into irony; part of what Beckett saw very clearly in Germany is that niceness does not save nice people from complicity. On the contrary: it may be precisely a conviction of the one that protects them from a consciousness of the other. But he certainly exercised, and would continue to exercise, a fine capacity for distinguishing between individuals and their platitudes or Quatsch.

Hence, as far as talking German is concerned, a different Beckettian project emerges in the shadow of the autodidactic one, a characteristically ironical project. However ‘absurd and inconsequential’ the logic, Beckett remarks that his drive to master another language is in fact a struggle ‘to be master of another silence’.28 Learning a language that he encountered in a historically specific and deeply rebarbative manifestation gave fresh impetus to his emerging concept of an art that might redeem the silence beyond language, not least, because, at a time when language is afflicted with historical disaster, silence must guard the principle of its possible renewal. Already, in Dream of Fair to Middling Women, he had written of Beethoven’s ‘vespertine compositions eaten away with terrible silences’, and of his music as a whole as ‘pitted with dire stroms of silence’ (DFMW, pp. 138–39). On 9 July 1937, not long after leaving Germany, Beckett wrote a famous German letter to Kaun which protests against the ‘terrible materiality of the word surface’ (DI, p. 172), and asks whether it cannot be dissolved into silence, ‘like for instance the sound surface, torn by enormous pauses, of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony’ (ibid.).

Thirdly: he immerses himself in art. Once again, however, those who approach the diaries expecting a sumptuous feast of criticism may possibly feel a bit cheated. In late 1936, Goebbels had declared the end of art criticism. Since the NSDAP was going to see to it that only good German art was displayed, there was no need for critics any longer. If he was aware of Goebbels’ directive, however, Beckett shows little inclination to resist it very spiritedly. The diaries include a few exquisite comments on individual works of art, notably regarding three great paintings, Giorgione’s Self-portrait, which Beckett saw in Brunswick, and Antonello da Messina’s St Sebastian and Vermeer’s The Procuress, which he saw in Dresden. Quite often, however, the moments of appreciation amount merely to brief expressions of taste. When Beckett likes paintings, he may note that they are marvellous, wonderful, magnificent, charming or lovely. He gives reasons for doing so only comparatively seldom.

But the reasons of course are self-evident. In Nazi Germany, loveliness was uniquely threatened. Beckett refused to accept the priorities that were making that possible, and the consequences of which he was hearing all around him. He brusquely dismissed both the Nazi taste in kitsch and art that stank of National Socialist propaganda (GD, 6.1.36, 4.1.37, 19.3.37). The day after an interminable harangue from Kempt on the Beer Hall putsch (1923) and the Night of the Long Knives (1934), he promptly sought refuge in the Kronprinzenpalais and bathed himself in De Chirico, Modigliani, Kokoschka, Feininger, Munch and Van Gogh. This was typical: he scathingly dismissed all talk of ‘politics’ (by which he meant Nazi talk), and concentrated on museums and paintings with a dedication which would seem almost obsessive, were it not so clearly an act of defiance.

This was particularly the case with modern art. From 1933, Alfred Rosenberg’s NS-Kulturgemeinde (National Socialist Cultural Community) and Goebbels’ rival Culture Chamber (the Reichskulturkammer) increasingly controlled art and culture in Germany.29 (Beckett heard others accuse Rosenberg, quite rightly, of being the principal foe of modern art in Germany, GD, 23.11.36). The new institutions proclaimed a new German art, and waged war on modernism. Beckett arrived in Germany at the end of a three-year period in which the Nazis had progressed from marginalizing modern art to banning it. The NSDAP increasingly instructed painters as to what, how much and where they could exhibit. Finally, on 5 November 1936, it ordered gallery directors to remove examples of decadent modern art from their walls. The purge would reach its climax in Munich in July 1937, with the Great German Art Exhibition on the one hand and the Degenerate Art show on the other.

Beckett was extremely conscious of how painters and paintings were affected by Nazi proscriptions. He knew very well, for example, how far, from 1933, the Machtübernahme had affected the painters of the Hamburg Sezession. Their working conditions had deteriorated, and opportunities for showing their work had dwindled. Some of them had been intimidated and denounced. Beckett specifically grasped the ‘inconsequence’ of National Socialist cultural politics, the result, not least, of disagreements between Goebbels and Rosenberg as to what actually constituted degenerate art.30 He found modern paintings still on display in some locations, in others not. He knew that certain museum catalogues had suddenly become inaccurate (GD, 30.10.36). He knew of painters who had disappeared or fled, like Campendonck and Klee (GD, 12.11.36), and those who were in disgrace (Marc, Werfel, Nolde, Feininger, Kirschner, Pechstein, Heckel, Grosz, Dix, Kandinsky, Schmidt-Rottluff, Baumeister, Bargheer, Barlach, GD, 10.11.36, 3.2.37). Beckett knew, too, that writers were suffering a similar fate. He learnt in October that the works of Heinrich Mann were no longer obtainable; then, in January, that Heinrich’s brother Thomas’s had also been banned (GD, 28.10.36, 11.1.37). He heard that other authors were also on the blacklist: Sauerlandt, Werner Mahrholz, Stefan and Anton Zweig (GD, 28.10.36, 2.11.36). He was advised not to read expelled authors (GD, 22.10.36) or certain histories of art and literature.

He knew that, whilst paintings were disappearing from gallery walls and being stuffed in cellars (GD, 30.10.36), it was sometimes possible to make a clandestine arrangement to see them. This, when he could, he did. He got the British Consulate in Hamburg to produce a letter supporting him in his efforts to see ‘forbidden’ art in the Kunsthalle and the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe. (The letter arrived too late to be of use.)31 He also visited private collections. He sought out painters and art historians, talked and listened to them. Quite a lot of the diary entries consist to some extent of lists: painters’ full names (underlined), often with their dates, their nationalities or places of origin, the schools to which they belonged. Sometimes the lists include titles of pictures. Beckett briefly describes certain pictures but not others. On occasions, he repeats details from one entry to another. He himself seems at one point depressed and exasperated by how far his diaries consist of such lists, and takes it to be a sign of obsessional neurosis (GD, 2.2.37). They served no purpose, he thought. Yet he also drew elaborate plans of floors in museums (the Kaiser Friedrich Museum and the Altes Museum in Berlin, the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, GD, 2.1.37, 27.12.36, 8.3.37), sometimes numbering the rooms. He sketched the screen of the western choir in the cathedral at Naumburg and the Goldene Pforte at the Freiberg cathedral, carefully noting the position of the figures (GD, 19.2.37). He drew a ground-plan of the Wallfahrtskirche at Staffestein (GD, 22.2.37). Once again, at such moments, he seems less concerned with art criticism than simply recording what is there, as though fearful it might soon be proscribed, or simply cease to be.

Beckett was obviously drawn into sympathy with German Jews, a sympathy he expressed in different ways, some more conscious or direct than others. He remarks on the desolation of the Jüdischer Friedhof in Hamburg (GD, 15.10.37). He notes his particular liking for a casual Jewish acquaintance, Professor Benno Diederich, and for another he remarks is married to a Jew, a stage decorator called Porep (GD, 25.10.36, 23.1.37). He made special efforts to meet and talk to Jews like Schapire and Will Grohmann, sacked director of the Zwinger Gallery in Dresden (a man sufficiently intellectual and brave to think, and tell Beckett, that it was more interesting to stay in Germany than to leave it, GD, 2.2.37). He took a particular interest in Jewish artists and art critics, like Wohlwill (GD, 24.11.36). He even sold what he had started to call his Hitlermantel, his leather coat (GD, 4.12.36, 13.2.37), and had a new suit made from materials supplied by Jewish dealers (GD, 23.2.37). At times, his disquiet emerges obliquely, as when he notes of Jacob van Ruisdael’s hauntingly beautiful painting The Jewish Cemetery that it may have been burnt by now (GD, 15.10.36). Whilst neither Jewish nor immediately concerned with Jews, Helene Fera, Chair of the University’s International Relations Office, the Akademische Auslandstelle, refused to be bullied by the Nazis and served as a crucial nexus for international student contacts in Hamburg. The most beguiling photograph in Roswitha Quadflieg’s account of Beckett’s weeks in Hamburg shows Fera, in 1936, pointedly surrounded by students of different races, notably Asians. Beckett thought of her as ‘the best of her generation, that I have met and will meet in this or almost any other land’.32

‘A haunting beauty’: Jacob von Ruisdael’s 17th-century The Jewish Cemetery.

Beyond all this, however, an intention hidden from Beckett also draws him into a different and more complex expression of sympathy. From the start of his trip, he conceives of Germany as bursting with poisons, thick with waste matter. When he heard Hitler and Goebbels’ speeches at the opening of the Winterhilfswerk, just four days after his arrival, he wrote that they would have to fight, ‘or burst’ (GD, 6.10.36).33 Wherever he turns, he runs into shit. The German press is full of it (GD, 3.1.37). Strangely, compulsively, his fastidiously sensitive body responds in kind. When he dismisses the notion of the German Schicksal, he adds that ‘the expressions “historical necessity” and “Germanic destiny” start the vomit moving upwards’.34 Attacks on modernist art in the press make him want to puke (GD, 15.1.37).

The theme of purging oneself of noxious waste is only partly metaphorical. It is also literal, physical. Beckett’s body starts to mimic the disorder he perceives around him. Thus ‘bursting’ is a word that recurs throughout the diaries. He repeatedly describes himself as bursting with wind or bursting for a piss or a shit. He suffers from diarrhoea, he fouls himself, he vomits. To anyone familiar with foreign travel on a limited budget, this may not seem very remarkable. What is remarkable is the repetitiveness of the details, their variety and the pains that Beckett takes to note them. That he pays them such sedulous attention suggests that he sees them as integral to his German experience as a whole. He has a pus-filled finger and thumb which he has to lance himself. He discovers lumps and boils under his scrotum and in his anus which seem eerily like fungoid growths. They also burst. His gorge rises. He experiences nausea. In Hitler’s Munich, not long before his departure, he abruptly declares that German food is awful, and, having eaten in Germany for several months, repeatedly wonders where one could possibly find food that one might stomach (GD, 9.3.37), eventually abbreviating the question, What can one eat? to the acronym w.c.o.e. (10.3.37).

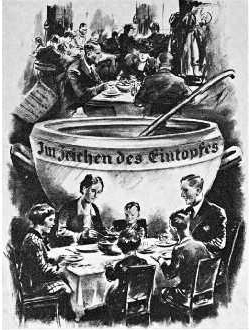

Eating well was an integral part of Nazi self-congratulation, as in this drawing in a February 1937 issue of the ss weekly paper Das Schwarze Korps. At the same time, Beckett was finding himself increasingly revolted by German food.

However obscurely, Beckett knew very well that Germany was caught up in convulsions, and about to convulse the world, with unpredictable but fearful consequences. He endured convulsions of his own. In London, he had gone to Bion partly because of physical symptoms which analysis seemed to alleviate, if not partially cure. However, Germany subjected him to physical upheaval all over again. His body became an inert cadaver that he had to drag out on to the streets in the morning. He frequently describes himself as crawling. He suffered repeated outbreaks of herpes on his lip. A raw wound on his back made him fear he might have VD (GD, 7.2.37). He was troubled by pains in his penis (GD, 5.3.37). The German Diaries make it harder to see Beckett’s physical condition in common-sense terms, as psychosomatic. His symptoms begin to seem more like manifestations of an almost terrifying susceptibility to the world around him. But he holds this exposure at one remove; hence his occasional professions of deadened feeling. All the same, he suffers. He suffers hopelessly, involuntarily and abjectly, because any other response would spell his own derogation. He suffers stoically, but with an agonized and almost spiritual intensity. His pain and wretchedness are at times appalling, and very moving.

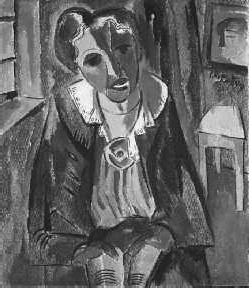

Just five days before he left Germany (GD, 28.3.37), he bought a great novel, Grimmelshausen’s Simplicissimus, remarkable for its magnificent, sombre if richly comic treatment of a Germany shattered (by the Thirty Years War). In ‘The Calmative’ (1946), Beckett would later also read ‘the contemporary landscape’ with reference to that particular European cataclysm.35 In early 1937, he wanders cheerlessly through a morally devastated landscape, one that would in due course of time be literally laid waste. He foresaw the likelihood of this, writing to MacGreevy of the possible destruction of Europe as early as October, 1936.36 At one particular moment in the diaries, so powerful as to seem almost vatic, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff’s portrait of Rosa Schapire leads him to a conception of art as prayer; prayer, that is, which ‘sets up prayer’, releasing prayer in another. As he himself succinctly explains: ‘Priest: Lord have mercy upon us. People: Christ have mercy upon us’.37

The Beckett astray in Nazi Germany, however, assumed the role less of priest than scapegoat, the ‘escape-goat’, the goat that, on the Day of Atonement, leaves the city, burdened with the sins of the people.38 To assimilate Beckett, here, however, in this precise context, to the Jewish scapegoat is to run the risk of a trivialization that he would himself have scrupulously deplored. In any case, it is not the Jewish scapegoat that Beckett in Germany most calls to mind, but the ancient Greek pharmakos.39 The pharmakos was often associated with poetry (Aesop, Hipponax, Tyrtaeus). He was ‘that which is thrown away in cleansing’. He was polluted, and bore ‘the plague of shame’ in a time of communal disaster.40 He might do so voluntarily (whatever will means, in this context). According to the most famous theorist of the scapegoat, René Girard, the pharmakos particularly appeared in times of violent conflict.41 He might be a foreigner (like the Cretan Androgeus in Athens) and have suffered a peripety from best to worst. The pharmakoi were rejecta: ugly, misshapen, foul. But they might also be the best of men, sacred figures, supreme (like Aesop) at intellectual pursuits. They were bearers of poison, but also the remedy for it.

‘Christ have mercy upon us’: Karl Schmidt-Rottluff’s Rosa Schapire, 1919.

It is the Irish equivalent of the pharmakos, however, that supplies the most arresting analogy to Beckett’s plight in Germany.42 Like other pharmakoi, though he might draw close to it and seek to exploit it, the Irish blame poet was implacably contemptuous of power. He was irreducibly at odds with it, in all its dispersed and winding ways, not least, when it was the power of a community united. Hence, sooner or later, he necessarily became an exile or outlaw. But he was also a histrion. His body mimed out what he saw. The shame, blemish and disgrace he perceived returned upon him. He might be leprous or otherwise diseased. He was often physically loathsome. At all events, the one invariable feature of the stories of the pharmakoi is their eventual departure from the city or fatherland. The German Diaries close as soon as Beckett leaves Germany. But according to Leviticus (16.22) the goat ‘shall bear upon him all their iniquities unto a land not inhabited’, that is, into the wilderness. For many years to come, artistically at least, the wilderness was to be Beckett’s home.