Beckett and Suzanne returned to Paris in November 1944,1 and went back to their former apartment, which now bore traces of being searched by the Gestapo. Beckett described the Paris of the time as ‘grim’.2 He sent his brother an eminently Beckettian telegram informing him that it was ‘IMPOSSIBLE TO MOVE AT PRESENT’.3 It was logical that he should have thought so. If his personal circumstances were not encouraging, nor were political conditions in Paris. But Beckett wanted to get back to Ireland, so he did move, after all, on 8 April. England greeted him as warmly as it had in the past. Immigration officials confiscated his passport, and the War Office asked him to explain his wartime absence from Britain. In London, he wandered through bomb-shattered landscapes. When he reached Ireland, however, like a man who feels set apart by his recent history, he steered clear of his former acquaintance. His sense of his own distance from them only increased when he heard the news of the death of his normalien friend and fellow résistant Péron in the concentration camp at Mauthausen. Soon he was ready to leave the British Isles again.

Fascinatingly, however, in spite of his decisive turn to France, the circumstances of his departure once again expressed some of the ambivalences of an Anglo-Irishman after Independence. In Dublin, he was very conscious of what seemed like Irish abundance, as contrasted with French deprivation. ‘My friends’, he remarked, pointedly meaning Frenchmen and women, ‘eat sawdust and turnips while all of Ireland safely gorges’.4 It was as though he were repeating the declaration of allegiance he had made in 1939. He was clearly unimpressed by Ireland’s neutral position during the war.5 Yet, at the same time, his next move brought him into line with de Valera himself. In a speech he broadcasted on VE day, Winston Churchill referred contemptuously to Irish neutrality. De Valera was not about to let this stand. On 16 May 1945 he responded, in what many Irishmen and women took to be his finest moment on the radio. Ireland’s task came now. ‘As a community which has been mercifully spared from all the major sufferings’, said de Valera,

as well as from the blinding hates and rancours engendered by the present war, we shall endeavour to render thanks to God by playing a Christian part in helping, so far as a small nation can, to bind up the wounds of suffering humanity.6

Beckett would hardly have seen himself as an emissary of the Taoiseach. Still less would he have been inclined to render thanks to God. Nonetheless, in early August, he joined ‘the Irish bringing gifts’ (CSP, p. 276), enrolling with the Irish Red Cross, and setting off for Saint-Lô.

The French called Saint-Lô ‘the capital of ruins’. The new arrival confronted a mind-numbing panorama of wreckage. ‘No lodging of course of any kind’, wrote Beckett, in the clipped, sepulchral tone that so many of his characters would soon be speaking in.7 Yet human creatures were surviving amidst the debris, scuttling out from cellars and scavenging amidst the ubiquitous mud. If this called certain scenes from Irish history to mind, it would not have been surprising. Beckett no doubt witnessed other horrors, or at least, their consequences. In ‘The Capital of Ruins’, written for Radio Éireann in June 1946, he talked about the frequent accidents resulting from falling masonry and children playing with detonators. He told MacGreevy that one of the Red Cross priorities was a VD clinic. By 1945, the war had made sexually transmitted diseases a crucial issue, not least because of the incidence of prostitution and rape. At all events, Saint-Lô was a place to learn, or to know yet again, that ‘“provisional” is not the term it was, in this universe become provisional’ (CSP, p. 278).

‘All is dark’, says Moran in Molloy, ‘but with that simple darkness that follows like a balm upon the great dismemberings’ (TR, p. 111). If any balm was to hand in France in 1945, events soon dissipated it. Beckett stayed in Saint-Lô until December 1945. Then he returned to Paris. Paris was home. There was no question of feeling distant from it. Indeed, Beckett had kept on making trips to Paris from Normandy. Since its liberation, however, by Allied Operation Overlord, in August 1944, Paris had become a special kind of beast. So, for that matter, had France. The Liberation was quickly followed by the Purge.8 The Purge is most notorious for the shaving of the heads of Frenchwomen supposed to have consorted with the enemy. In actual fact, it was a far more protracted and complex phenomenon than a single image can suggest. There were at least three stages to it. In the first and most obviously shocking, the épuration sauvage, which included the shavings, outraged Frenchmen and women, some of whom had not been much less complicit with the Germans than their victims, nonetheless took revenge – on occasions, murderously – on those they deemed to have been collaborators. Some of the direst features of Vichy France – special courts, internments, denunciations, arbitrary arrests, atrocities as committed by Pétain’s paramilitary Milice, even torture – were duly maintained in the hands of its enemies. Improvised courts martial took place. Collaborators were held on the very sites where Vichy had detained French Jews. The widespread practice of ‘popular justice’ might mean execution without trial. Its victims died in the street, in their houses or at the hands of lynch mobs. Sartre thought that France was in danger of collapsing into ‘mediaeval sadism’.9

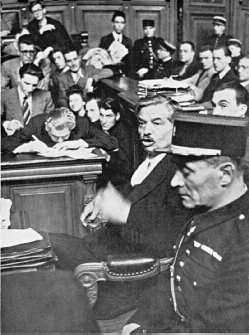

The épuration sauvage: Frenchmen take their revenge on perceived collaborators with the German occupiers.

The épuration legale that followed the initial barbarisms, however, was scarcely a paradigm of justice restored. De Gaulle was now the President of the Provisional Government of the French Republic. The Gaullists had established a purge committee as early as 1943, to provide a legal system for the trial of collaborators. In 1944, before France had a new constitution or the French had elected a new parliament, they instituted new courts of justice. The new juridical formulations were extremely severe. ‘Rarely have such authoritarian provisions been instituted by a regime founded under the sign of liberty’, wrote the distinguished historian Robert Aron.10 Those responsible for the provisions in question were particularly concerned to simplify the arrangements and procedures of previous French court systems, with one judge as opposed to the traditional three, and six jurors as opposed to twelve. At the same time, Gaullists, Communists and socialists all used the courts for political ends. Travesties of justice were bound to result, the most egregious instance being the Laval trial. Laval’s conduct was hardly defensible. At the same time, his trial was a charade. Witnesses went unheard in the pre-trial interrogation. Crates of evidence were left unopened. Some of the statements read out did not even concern Laval. Jurors bawled at him: ‘Bastard!’ ‘You’ll get a dozen bullets!’ ‘You’ll yell less loudly in a fortnight!’.11 So unedifying was the spectacle that it prompted at least one Jewish journalist to take Laval’s side.12

The trial of Vichy Prime Minister Pierre Laval, October 1945.

The Gaullists also invented a new concept, indignité nationale. They wanted it to cover acts of collaboration not previously specified as crimes. It did not imply collusion with the enemy, or even the breaking of a law. In certain circumstances, the guilty party needed only to have made ‘scandalous’ remarks.13 The concept of indignité nationale declared that what mattered was not what one had done under Vichy, but what one was supposed to have been. The punishment was dégradation nationale: shame, loss of status, the proclamation of one’s ‘unworthiness’. Unfortunately, at the time, French political and judicial praxis and the attitudes of many Frenchmen and women markedly lacked the sense of principle that might have ensured the moral credibility of such concepts. Local people and press frequently influenced courtroom proceedings. Juries were blatantly packed. Judges passed sentences that were harsh and undiscriminating to the point of being dismayingly unjust. Even the battle-hardened General Eisenhower was genuinely shocked. It was hard to tell where ‘national degradation’ began and ended. Apart from appalled crusaders like Jean Paulhan, few seemed truly to rise above it. France itself was writhing in agony at its own recent indignity.

Certainly, in a third phase, the Purge became less draconian. By 1949, the Court of Justice was less in evidence, and judges were more likely to suspend sentences or make them more lenient. De Gaulle and others distributed pardons and amnesties. Increasingly, people agreed that the Gaullists had not constituted the courts with due care and forethought. Thus Pétain himself, whose trial came later, did not meet with the same fate as Laval. Purge victims started telling their stories. The authorities discreetly rehabilitated some of them. In 1950, the Union pour la Restauration et la Défense du Service Public formally condemned the postwar French government, declaring that it had created a repressive apparatus without precedent in history which had attacked free speech, punished political error, stifled freedom of thought and assembly, accepted retroactive legislation and rejected the principle of criminal intent. This was both a soberingly clear-eyed assessment of recent malpractice, and a token in itself that matters were on the mend. When the Amnesty Bills of 1951 and 1953 came into effect, the process of relaxation was in some respects complete.

But reprieves can be unjust, too. Perhaps the most obvious example of this in post-war France was Papon. During the war, Papon had regularly collaborated with the ss in its persecution of the Jews in the Gironde. De Gaulle apparently knew this. Nonetheless, though Papon was censured after the war, he bounced back, eventually rising as high as Minister of the Budget under Giscard d’Estaing. His recovery was quite typical of the later stages of the Purge. Falsifications of recent history became common. Petainists quietly re-installed themselves in French society. Neo-Vichyites increasingly thrived. Former Vichy officials claimed they had been trying to protect France and French civilians from the Occupation and Nazi policies. They even asserted that, by not promptly handing French Jews over to the Nazis, Vichy had actually done what it could to protect them.

In any case, collaborators were not the only ones who were busily rewriting contemporary history. It was de Gaulle above all who was responsible for the post-war myth of heroic France. In a famous speech of 25 August 194414 he played down Allied involvement in the Liberation. He spoke rather of a Paris freed by its own people ‘with help from the armies of France, with the help and support of the whole of France, of France which is fighting, of the only France, the real France, eternal France’. He minimized the evils of Vichy, even though the regime itself had condemned him to death for treason. De Gaulle admitted that ‘a few unhappy traitors’ had given themselves over to the enemy. He could hardly do otherwise. But the Resistance had been heroic, and the majority of the French had conducted themselves as ‘bons français’. They had liberated themselves by their own sterling efforts. According to historian Robert Gildea, the ‘mythic power’ of this gospel was extraordinary.15 It persisted far beyond de Gaulle’s resignation (in 1946). Nearly four decades later, Marguerite Duras could still quote in anger de Gaulle’s eminently un-Beckettian message: ‘“The time for tears is over, the time of glory has returned”’.16

For Duras, these words were ‘criminal’. ‘We will never forgive him’, she wrote. De Gaulle declared that ‘in the moral realm, seeds of dissension exist and must be eliminated at all costs’.17 His primary concern was the unity of France, even at the expense of historical truth. It was the cause of unity that the Gaullist mythology served. But de Gaulle’s purposes were self-defeating. Initially, at least, before it triumphed as the official story, the mythical narrative was bound to produce yet more of the very dissension it was supposed to quash. Questions of justice, guilt and punishment were widely raised and debated in both the national and the provincial press. It is inconceivable that Beckett, a reader of newspapers, was not aware of this. Other versions of recent history soon started competing with the Gaullist narrative, sometimes splitting communities as they did so. But above all, it was the literary world that called the Gaullist project into question. Writers were unlikely to smother dissent. They were much more likely to express and breed it. De Gaulle however, had seen this coming. He was well aware of how crucial the interventions of writers could be. He roundly declared that two kinds of collaborator deserved neither pity nor commutation of the death-sentence: army officers and talented writers.18

Not surprisingly, thus, whilst collaborationist lawyers, businessmen and newspaper magnates frequently passed unnoticed or got off scot-free, Gaullist France repeatedly put writers on trial. The blacklist included the names of Montherlant, Céline and Drieu la Rochelle. It also included Jean Giono, though he had helped both Jews and Resistance fighters. That the inspirational publisher Bernard Grasset had brought Proust, Malraux and Mauriac to the attention of the world did not save him from the charge of collaboration on the basis of an anonymous denunciation. The relevant court found Grasset guilty in 1944: he returned to directing his publishing house only in 1950. At the same time, collaborationism also provoked controversy among writers, including Sartre, de Beauvoir, Camus, Cocteau, Valéry and François Mauriac. Here, again, the ‘seeds of dissension’ flourished and spread. Novels like Jean-Louis Curtis’s Les forêts de la nuit (1947) and Jean Dutourd’s Au bon beurre (1952) examined the question of personal morality under Vichy, whilst others like Marcel Aymé’s Uranus (1948) turned a critical or satirical eye on French Communists and Resistance heroes. If Beckett had been indifferent to French literary politics between 1944 and 1949 – and therefore to the country at whose ‘disposition’ he had emphatically placed himself in April 1939, to which, on 4 September of the same year, he so decisively returned, and for whose cause he then chose to work – he would have been very unusual among Francophone novelists.

Beckett knew of much of the worst of what took place in France in the immediately post-war years. He returned to Paris at a time when the atmosphere was one of terror.19 Under the heading ARRESTS AND PURGINGS, Figaro was publishing daily lists and accounts of summary justice and executions. Readers could get similar information in Combat and elsewhere. Beckett clearly knew that, ironically enough, others were claiming that the horrors were taking place so that the Nation could ‘proceed calmly to heal [its] wounds and rebuild’.20 In ‘La peinture des van Velde ou le Monde et le Pantalon’, for example, written soon after the end of the war, he scathingly declared that, though seemingly lacking the humanity mandatory after a cataclysm, the van Veldes’ painting in fact contains more of it than ‘toutes leurs processions vers un bonheur de mouton sacré’. He clearly did so with the French context and specifically the excesses of the Purge in mind, not least because he added a reference to the painting being stoned (‘Je suppose qu’elle sera lapidée’, DI, pp. 131–2). He was also conscious of the new cult of heroism. As one of those deemed to have contributed most to liberation through participation in the Resistance, he had himself received the Croix de Guerre, in 1945. The citation, signed by de Gaulle, described him as ‘[a] man of great courage’ who ‘carried out his work with extreme bravery’.21 It was not the way he would have seen himself. In any case, the very France that now abounded in heroes and was busily feting returned political deportees was also slighting or ignoring its labour deportees, returning prisoners of war and Jews.

Beckett had already come across one version of the new French chauvinism in Saint-Lô, where the local French wanted Irish supplies but not the Irish.22 In ‘The Capital of Ruins’, he stoutly resisted Gaullist Francocentrism, insisting on a kind of part-mutuality. It was ‘the combined energies of the home and visiting temperaments’ that really mattered, ‘the establishing of a relation’ between the Irish and ‘the rare and famous ways of spirit that are the French ways’. For the ‘proposition’ underlying the pains the Irish took was that ‘their way of being we, was not our way and that our way of being they, was not their way’ (CSP, p. 277). Liberation, however, did not put a speedy end to the privations and constraints from which the French had suffered, and which Beckett and Suzanne shared. The Paris to which Beckett returned from Saint-Lô was a sombre city of darkened buildings and chronic shortages. What he called his poverty had never distressed him before, and would not unduly do so now. But the moral crisis that France itself was undergoing was a different matter. ‘The news of France is very depressing, depresses me anyhow’, he wrote to MacGreevy, in 1948, just before beginning the Trilogy. ‘All the wrong things, all the wrong way. It is hard sometimes to feel the France that one clung to, that I still cling to. I don’t mean material conditions’, he added, with emphasis.23 If the France Beckett loved seemed in danger of vanishing, this was partly because Vichy cast such a long shadow. Many of the restrictions for which the Vichy government had been responsible simply remained in place after liberation. But it was not merely in the political sphere that ‘all the wrong things’ were taking place. The rot had entered the most intimate, inward and private spheres of French life. Suspicion was pervasive, and would remain so for some time to come, as the novels of Nathalie Sarraute so powerfully demonstrate. There was widespread corruption, and callous indifference to the recent sufferings of others.

These, then, were the features of Beckett’s world as, between early 1946 and January 1950, he immured himself and wrote Mercier and Camier, his four Stories (‘First Love’, ‘The Expelled’, ‘The Calmative’ and ‘The End’) and, above all, from May 1947, his great masterpiece, the Trilogy. He called this the period of his ‘siege in the room’.24 He would resort to metaphors of the battlefield later, too, as, for example, when he owned a house near the Marne, he described himself as ‘struggling’ with work in progress in his ‘hole in the Marne mud,’ or ‘crawling up’ on it from ‘a ditch somewhere near the last stretch’.25 In the German Diaries, he calls his inner world his ‘no man’s land’ and refers to ‘phrases rattling like mashinegun [sic] fire in my skull’.26 Such images are obviously significant, above all, for the Trilogy. The Trilogy is everywhere haunted by a vocabulary and images that call modern warfare and its consequences to mind: combustion, detonation, upheaval, crawling, scavenging, ambulances, boots, crutches, rations, ramparts, observation posts, guardrooms, hospitalization, annihilation, loss of limbs, amputation, lightlessness, sheltering in holes, violent encounters in forests, battle-cries, cries in the night, murder, immolation, blackouts, amnesias, extermination, regiments, returnees, war pensions, mutilation, enlistment, puttees, disfiguration, dust-clouds, festered wounds, tyrants, craters, mass burial, cenotaphs, greatcoats, memoirs, mud, decomposing flesh, bodies becoming shapeless heaps or living torches, uprooting, dislocation, and above all, ruins, ‘leaning things, forever lapsing and crumbling away’ (TR, p. 40). The protagonists of the Trilogy all make halting progress over featureless or shattered terrain.

This amounts to a (by no means exhaustive) draft inventory of one aspect of Beckett’s fantasmagoric stock-in-trade in the late 1940s. Indeed, juggle the pieces, and the Trilogy supplies one with a clutch of phrases for a hauntingly vivid and wastefully well-told war story. Malone’s ‘black unforgettable cohorts’ that sweep away the blue (TR, p. 198); the Unnamable’s ‘lights gleaming low afar, then rearing up in a blaze and sweeping down on me’ (TR, p. 352); its ‘small rotunda, windowless, but well furnished with loopholes’ (TR, p. 320): all could be adjusted to such a purpose. The condition of war victims is repeatedly perceptible in the background of the Trilogy: the ‘burnt alive’, rushing about ‘in every direction’ (TR, p. 370); Malone’s ‘incandescent migraine’ (‘My head. On fire, full of boiling oil’, TR, p. 275); the Unnamable’s ‘nerves torn from the heart of insentience, with the appertaining terror and the cerebellum on fire’ (TR, p. 352). Malone’s reference to the ‘noises of the world’ having become ‘one vast continuous buzzing’ (TR, p. 207) calls sufferers from shell-shock to mind. If Molloy, Moran, Malone and the Unnamable’s world is one beleaguered by ‘the inummerable spirits of darkness’ (TR, p. 12), in which ‘everything is going badly, so abominably badly’ (TR, p. 375), as such, it is clearly conditioned by recent historical and Beckett’s own personal experience, if not directly identifiable with them.

So, too, the shadowy world of the Resistance and the Gestapo also leaves its traces in the Trilogy. Ciphers, reports, safe places, objectives, missions, garrotting, the rack, interrogators, secrets, agents, false names, beatings, surveillance, betrayal, provisions, prison cells, night patrols, mutual wariness, terrified neighbours, ‘deeds of vengeance’ (TR, p. 131), concealment of relatives, torture by rats, ‘peeping and prying’ (TR, p. 94), furtive whisperings, surreptitious poisonings, instructions from a chief, ‘gaffs, hooks, barbs’ and ‘grapnels’ (TR, p. 362), gloves worn ‘with all the hard hitting’ (TR, p. 350), confession, especially of names, or ‘piping up’ (TR, p. 378), auditors who ‘listen for the moan that never comes’ (TR, p. 371), writing to order and for collection (as Beckett did for Gloria): all make their appearance, in some form or another. Moran declares himself to be ‘the faithful servant … of a cause that is not mine’ (TR, p. 132), as Beckett was himself.

More remarkably still, there is much in the Trilogy that calls the climate of the Purge to mind. The parallels between the Trilogy and the literature and journalism that, from the mid-to late 1940s, increasingly drew widespread public attention to the brutal practices in the Purge prisons have yet to be properly examined, but undoubtedly exist. More generally, the Unnamable inhabits a world where ‘you must accuse someone, a culprit is indispensable’ (TR, p. 415). Here one must look innocent at all costs, like the ‘bloodthirsty mob’ in Molloy with ‘white beards and little, almost angel faces’ (TR, p. 33). The Unnamable sees through this world with shattering lucidity:

We were foolish to accuse one another, the master me, them, himself, they me, the master, themselves, I them, the master, myself … this innocence we have fallen to, it covers everything, all faults, all questions, it puts an end to questions. (TR, p. 379)

There are few passages with more resonance in the Trilogy as a whole. In less sophisticated vein, Molloy excoriates the ‘righteous ones’, the ‘guardians of the peace’, with their ‘bawling mouths that never bawl out of season’ (TR, p. 35). Malone’s world is one of pursuits and ‘reprisals’, haunted by the the threat of being ‘hounded’ by ‘the just’ (TR, p. 195, 276). Moran links rage with ‘the court of assizes’ (TR, p. 127). The Unnamable associates persecution with an assembly of ‘deputies’ (TR, 315).

It is Molloy, however, who most vividly evokes both the violence and the habit of doublethink that plagued France for at least a decade:

Morning is the time to hide. They wake up, hale and hearty, their tongues hanging out for order, beauty and justice, baying for their due…. It may begin again in the afternoon, after the banquet, the celebrations, the congratulations, the orations … the night purge is in the hands of technicians, for the most part. They do nothing else, the bulk of the population have no part in it, preferring their warm beds, all things considered. Day is the time for lynching, for sleep is sacred. (TR, p. 67)

Self-evidently, this is not a direct evocation or historical representation. As with the references to the War and the Resistance, however, what is at stake is not only dispersed images and scattered words and phrases, but images whose historical content has been displaced, language whose allusion to historical realities is characteristically oblique.27 The obliquity is crucial, as is the sporadic and unreliable Irishness of the characters, in holding the historical material at a remove. But the point par excellence, of course, is that history in the Trilogy exists as rubble, as debris strewn across its pages. The historical deposits in question constitute much of Beckett’s imaginative raw material during this period. The Trilogy presents us with a (suitably distant) mode of treating and transmuting them. The question, finally, is what exactly that treatment involves.

The characters in the Trilogy themselves bear many of the marks – indignity, degradation, shame, suspicion, cruelty, voluntary anaesthesia, a tainted past, a bitter knowledge of repression and injustice – that had disfigured France after its defeat. So, too, up to a precisely delimited point, in their rage, their outbursts and recriminations, their lapses into furious incoherence, they are close in tone to the atmosphere of post-war France as crystallized, for example, in the transcripts of the Laval trial. This is above all the case with The Unnamable. The theme of the relationship between justice and speech looms large in both novel and trial. Unlike the Unnamable, however, Laval decided not to go on, choosing silence before the process had ground to its inevitable conclusion. Above all, the impassioned self-torment in which the characters of the Trilogy are caught up, their tumultuous, anguished quarrels with themselves, both internalize something of the condition of France itself, and function as a metaphor for and analogy to it.

In all of these respects, the Trilogy seems to insist on a cultural temper whose memory de Gaulle, his allies and successors were concerned briskly to expunge. Here Beckett seems very close indeed to Duras, of whom we know he approved.28 The intransigent anti-heroism of the Trilogy represents a fierce repudiation of the ethos of post-1944 Gaullist France, its insistence on renewal and purification, its rewriting of the recent past. If the ‘people’ in Molloy ‘so need to be encouraged, in their bitter toil, and to have before their eyes manifestations of strength only, of courage and of joy’ (TR, 25), neither Molloy nor Beckett himself will pander to that need. Deliberately, and at times derisively, Beckett toys with the language and symbols of the Gaullists. Malone’s automatized profession of loyalty is strictly ironical:

Yes, that’s what I like about me, at least one of the things, that I can say, Up the Republic!, for example, or, Sweetheart!, for example, without having to wonder if I should not rather have cut my tongue out, or said something else. Yes, no reflection is needed, before or after, I have only to open my mouth for it to testify to the old story. (TR, p. 236)

When Moran whimsically imagines being left trailing ‘like a burgess of Calais’ by his son (TR, p. 129), he is indexing a classic point of reference for heroic French nationalism. It is even not inconceivable that Molloy’s object resembling ‘a tiny sawing-horse’ (TR, p. 63) is a trivially distorted, absurdly ironical version of the Cross of Lorraine,‡, the symbol of Joan of Arc, another such point. After 1944, in a slightly different form, as the symbol of the Free French Forces and the United Resistance Movement, it was visible everywhere in France, from flags to helmets.29 French humourist Pierre Dac promised collaborators that, by the time the Purge was ended, they would be ‘nothing more than a small heap of garbage’.30 ‘Tout est dit. A la poubelle’ (DI, p. 131): with the declaration that someone is less than properly human, everything seems said, and one can consign the entity in question to the dustbin. By contrast, Beckett himself stubbornly constitutes his characters as (and sometimes literally in) Dac’s heaps. His interest is in human rubbish per se, not as the antitype of regenerate man.

The Unnamable, above all, is the character in Beckett’s writings in the 1940s who seems most determined to resist the rousing tones of Gaullism, or at least, the specious exhortations to positivity of which Gaullist France no doubt enhanced his sense. The Unnamable hears a lot of stirring talk: ‘They have told me, explained to me, described to me, what it all is, what it looks like. And man, the lectures they gave me on man, before they even began trying to assimilate me to him’ (TR, p. 326). The voices in question want to elevate the Unnamable above itself, to ‘decoy’ it into a superior ‘condition’ (TR, p. 363). They therefore alternately assure it that ‘the big words must out’, and ‘plaster’ it with their bilge or Quatsch (TR, p. 341). They try to convince it of eternal truths. But there is nothing timeless about these voices. Their grandiosely humanistic rhetoric is historically specific: it was common currency in the smashed cultures of the former belligerents during the first two or three decades of the postwar recovery. This would hardly have surprised Beckett, who thought there was an intimate relation between ‘pestilence or Lisbon or a major religious butchery’ and the birth of noble sentiments (DI, p. 131). The deep Voltairean streak in him is unmistakeable here. His principal experience of the kind of voices with which the Unnamable struggles was through Gaullism. He understood their humanism as a failure of sensibility and intellectual courage. He also knew that they incessantly created or reproduced the very problems they aimed to solve, threatening a return of ‘the incriminated scenes’ (TR, p. 318):

They gave me courses on love, on intelligence, most precious, most precious. They also taught me to count, and even to reason. Some of this rubbish has come in handy on occasions, I don’t deny it, on occasions which would never have arisen had they left me in peace. (TR, p. 300)

Underlying the mood of ‘recovery’ was drastic and irreparable loss. Beckett’s post-war work is steeped in it. The Unnamable speaks out of an awareness of historical damage not readily to be mended, if at all. Its situation may be irredeemable.

Irredeemable, certainly, in the terms of Charles de Gaulle: the voices want the Unnamable to forget its pain, or be at worst modestly pained. They want it to proclaim its ‘fellowship’ with them and ‘swallow’ its ‘fellow creatures’ in general (TR, pp. 300, 327). In the spirit of the times, they want above all to see it reconciled. That is, they want it ‘loving [its] neighbour and blessed with reason’ (TR, p. 338). They want it to acknowledge the prevalence of justice and harmony. But the Unnamable adamantly refuses to be dragged out into the light of the true, the good and the right. It is inveterately and invigoratingly hostile to any form of uplift:

Ah but the little murmur of unconsenting man, to murmur what it is their humanity stifles, the little gasp of the condemned to life, rotting in his dungeon garrotted and racked, to gasp what it is to have to celebrate banishment, beware. (TR, p. 328)

In this, it is faithful to one of Beckett’s deepest inspirations, whilst also repudiating the mode and tone of the historical rescue packages so relentlessly doled out to modern man.

Like Molloy, Moran and Malone, again, the Unnamable is, in its way, a scapegoat, loaded down with a consciousness of the sins that others are anxious to shrug off. If Girard is the great theorist of the scapegoat, its great archivist is Sir James Frazer. In two volumes of The Golden Bough, The Dying God and, in particular, The Scapegoat, above all 4.3, ‘The Periodic Expulsion of Evils in a Material Vehicle’, Frazer tells us of the attempts made by many communities ‘to dismiss at once the accumulated sorrows of a people’ by draping figures in the baleful tokens of recent historical evils.31 Amongst the Iroquois, the men of the village actually went about collecting these tokens. Scapegoats were sometimes holy ascetics, as in the Jataka. But they often cut a more melancholy figure than that. The scapegoat could be sick, diseased, debilitated, grotesque or sinful, ‘broken down by debauchery’.32 Certain communities specifically laid ‘the painful but necessary duty’ on ‘some poor devil, some social outcast, some wretch with whom the world had gone hard’.33 Significantly for the Trilogy, men and women might choose the role of scapegoat voluntarily, ‘diverting evils threatening others to themselves’.34

The characters in the Trilogy bear the burden of contemporary history like scapegoats. But as scapegoats, they do not just suffer. Beckett puts them to work. ‘How [can we] live without bitterness and without hatred in the vicinity of criminals and traitors, even if they are well locked up?’ asked an outraged French correspondent of La résistance savoyarde soon after the war.35 The Trilogy responds to this kind of question with a concept of ‘living with’ that is also one of ‘working through’. Beckett had always been interested in the idea of ‘continuous purgatorial process’ (DI, p. 33), associating it with Joyce’s treatment of ‘the vicious cycle of humanity’ (ibid.). The Trilogy rejects any quick solution, notably in narrative terms. As a response to contemporary France, it counters purges with purgatorial labour. ‘They loaded me down with their trappings’, says The Unnamable, ‘and stoned me through the carnival’ (TR, p. 327). He calls to mind many pharmakoi stoned before him, like Eumolpus in the Satyricon. Eumolpus is impoverished, intellectual, inept, ‘a tattered thing’ and ‘cold scarecrow’. He is stoned in the temple for caring about language and ‘the loveliest of the arts’, and reciting good poetry in an inimical world (in his case, Nero’s Rome).36 The Unnamable’s sentence may possibly derive partly from 9 February 1937 in Dresden, where Beckett prudently avoided being out on Faschingsnacht (GD, 9.2.37). We shall hear more of him stumbling through the postwar carnival shortly.