The gloom of What Where might have seemed appropriate enough in 1983, the climax of a little period that, from 1979, seemed to promise the resurgence of a brutal international politics. By 1986, however, as far at least as the Cold War was concerned, matters wore a different complexion. In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in the Soviet Union. The Soviet economy was heading for disaster. Gorbachev saw this, and sought to turn it in a different direction. His policy of perestroika directed funds away from military and towards civilian uses. The glasnost that accompanied it meant that the Communist regimes became more open and transparent, and admitted the justice of criticism from within. The Soviet bloc increasingly brought the abuses that Catastrophe and What Where had partly addressed to a halt.

Reagan and Thatcher scented justification and ideological victory, not least because the West was experiencing an economic boom. Reagan agreed to scale down the arms race, and, in a series of summits ending in Moscow in 1988, both sides drastically reduced their nuclear arsenal. By the late 1980s, a new breed of what Beckett had called the ‘hardened optimists’ (MU, p. 157) – brusquely self-cauterizing, impatient to forget the wounds of the world – were talking of the emergence of a ‘new world order’. The term first appeared in 1988. In 1989, Francis Fukuyama published an essay entitled ‘The End of History?’, anticipating his book of 1992, The End of History and the Last Man, in which he argued that humanity had arrived at the telos of its evolution as exemplified in Western democratic societies.1 Shortly after the essay appeared, Beckett died.

‘His era was over’: Beckett in Paris, late in life.

It was as though he knew that the era that had shaped him and determined the character of his art was over. However, he would certainly not have responded to the concept of ‘the end of history’ with anything other than hawk-eyed scepticism. So much is clear from that great work of his final years, Stirrings Still (1988):

So on unknowing and no end in sight. Unknowing and what is more no wish to know nor indeed any wish of any kind nor therefore any sorrow save that he would have wished the strokes to cease and the cries for good and was sorry they did not. (CSP, p. 263)

Just a month before his death, the Berlin Wall, of which he had been conscious for so long, finally came down. By then, Beckett’s own particular corner of the new world order was Le Tiers Temps, an old people’s home. Rather than rejoicing with the optimists, or indeed, celebrating at all, he appeared to be acutely anxious. Having watched some television footage from Berlin in his room, ‘he emerged very agitated’ and exclaimed to the directrice, Madame Jernand, ‘Ça va trop vite’.2 It is a luminous moment. To attribute Beckett’s ‘agitation’ simply to debility finally unstringing the nerves would be to diminish him. He had always nursed a sage and clear-eyed distrust of any solution ‘clapped on problem like a snuffer on a candle’ (DI, p. 92).3 ‘Ça va trop vite’ had formed part of his injunction to Ireland in the 1930s, and to France and the world immediately after the war.

‘They loaded me down with their trappings and stoned me through the carnival’ (TR, p. 327): Beckett did not survive to witness most of the developments after Gorbachev conceded victory to the Western way of life. There are few if any less Beckettian spectacles than the eudemonistic carnival of triumphant Capital – the champagne culture – that followed the end of the Cold War (at least, as far as 2008). It is hard to imagine him fitting in. Or is it? The irony in the Unnamable’s remark is very delicately judged. As a writer who claimed to have breathed deep of the vivifying air of failure all his life, Beckett hardly understood self-satisfaction. He was a faster not a feaster, as Coetzee says of Naipaul, in a modern world which offered ‘less and less of a home to the fasting temperament’.4 Yet, as he grew older, his modus vivendi was by no means radically at odds with post-war European, affluent middle-class norms. True, he told Barney Rosset in 1958 that he wanted to ‘put a stop to all this fucking élan acquis and get back down to the bottom of all the hills again, grimmer hills than in ’45 of cherished memory’. He was, he feared, in danger of finding himself ‘entangled in professionalism and self-exploitation’.5 Nonetheless, in many respects, he bore the ‘trappings’ of his success sedately if not comfortably.

Indeed, given that he intensely disliked celebrity – he shunned publicity, turned down most of the honorary degrees he was offered and, when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1969, did not attend – he might even seem to be an example of what Fukuyama called the ‘last man’, short on thymos, the will to win recognition, but much concerned with inconspicuous self-preservation. Knowlson comprehensively demonstrates how far the later Beckett was caught up in and reconciled to a conventional and even stolid version of the lifestyle of the post-war bourgeois professional. He had two residences, city and country, and discussed his commuting arrangements with friends. He quarrelled with others over building rights on neighbouring land. He was weighed down with correspondence, made and kept endless appointments, took jet flights and argued over contracts. In the rapidly consumerizing 1950s, he acquired the usual spoils: car, television, telephone. He had separate telephones for business and private life. He planted trees in his garden at Ussy, worried about the state of his lawn, took long recreational walks and listened to sport and classical music concerts on the radio. He married Suzanne. But they also led increasingly separate lives, and Beckett had affairs. He developed particular tastes in food and drink and worried about his heating and his addictions to alcohol and tobacco. He was sometimes worn out by rush and bother, and took holidays in sunny places, increasingly for reasons of health.

‘Histoire banale’, as he said of Play,6 a work which, in its own fashion, is about modern life, or at least, modern adultery. There are two key aspects of the later Beckett, however, which run counter to this description of him. The first, of course, is his later writing, which explores zones of experience and sensibility quite beyond the usual horizons of middle-class life, and posits a concept of ‘last men’ (and women) extremely remote from Fukuyama’s thesis. The second is his attitude to money and possessions. During his time in London, Beckett had lent Tom MacGreevy money, at the same time urging him that there should ‘never be any talk of debts and loans and all the other lousinesses of give and take entre ennemis between us. When it’s there it’s there and when it’s not it’s not and basta’.7 This was to prove characteristic of him. He was an admirably, casually, prolifically and almost alarmingly generous man. He gave spontaneously, with no thought of getting back. He was seemingly quite indifferent to what Marx called exchange value and Murphy thinks of as the rule of the quid pro quo. It was a feature he shared with some of his contemporaries at the École Normale, who were mindful of the normalien code of heedlessness of self. Sartre, for example, had little or no interest in creature comforts, did not have a bank account and gave money away to friends throughout his life.8

Thus when Ethna MacCarthy fell ill, Beckett offered to help her with money ‘up to the limit’.9 He waived all fees for Rick Cluchey’s production of Endgame, and gave money to Cluchey and his family. He gave away the Jack Yeats painting he owned and loved (to Jack MacGowran). He paid the tax bill of his friends the Haydens, helped the MacGowran family when Jack died, and paid money into the trust fund for the children of Jean-Marie Serreau, a man he did not like, just as, years earlier, in Germany, he had made the acquaintance of Arnold Mrowietz, a part-time tailor who repelled him, and then ordered a suit from him. He supported the insignificant young writer Jean Demélier, and bought him ‘an entire wardrobe’.10 He frequently gave cash to charities and family members. He paid for friends’ holidays. He gave away his Nobel prize money (to some very good causes, like B. S. Johnson and Djuna Barnes). At the same time, he himself showed a ‘total lack of interest in any kind of luxury or display’,11 and his apartment and house in Ussy were furnished with Spartan simplicity. He was even remarkably cavalier about parking fines. Cronin tells a fine story of Beckett’s kindness to two porters from Dublin’s National Gallery who decided to holiday in Paris. (He took them everywhere from the Louvre to a brothel in Montparnasse.)12 But if one story particularly illustrates Beckett’s disdain for ‘give and take entre ennemis’, it is Claude Jamet’s account of the night when a tramp approached him in a Montparnasse bar and complimented him on his jacket. Beckett promptly took the jacket off and gave it to him. ‘Without emptying the pockets either’.13

Put Beckett’s profligacy together with his minimalism, the wilful self-destitutions of his art, and it might seem logical to conclude that his aesthetic is levelling, and even egalitarian. He insisted, after all, on the fact and the importance of ‘being without’, in more senses than one (DI, p. 143). He stated that ‘my own way was in impoverishment’ and spoke of his ‘desire to make myself still poorer’.14 He dreamt, he said, ‘of an art unresentful of its insuperable indigence’ (DI, p. 141). Troublesomely, however, he seems dismissive of egalitarians themselves. Take, for example, his satirical account of the political agitator in The End:

He was bellowing so loud that snatches of his discourse reached my ears. Union … brothers … Marx … Capital … bread and butter … love. It was all so much Greek to me. (CSP, p. 94)

‘He had a nice face’, adds the narrator, ‘a little on the red side’ (CSP, p. 95); but this abrupt cluck of liking hardly encourages more respect for the man’s views. That Beckett worked a deliberate reference to the ‘Marx Cork Bath Mat Manufactory’ (MU, p. 46), whose existence he had noted in London, into Murphy confirms the impression of a detachment from political radicalism that bordered on flippancy, and even derision.

Still more problematically, Steven Connor has shown that the difficulty with reading Beckett in terms of economics is that, in his work, less keeps on turning out to mean more. On the surface of things, Beckett’s ‘poetics of poverty’ reflects a determination ‘to resist not only the values of the commodity and the market-place, but the value of value itself’. Alas, however, negativity itself insidiously keeps metamorphosing ‘into different varieties of positive value’.15 Publishing houses, the institutions of the performing arts and academic scholarship and criticism all unceasingly convert Beckettian minimalism into profit. The Beckett industry has become one of the largest and most distinctive multinational corporations in the literary world. Furthermore, with Worstward Ho as his example, Connor shows how far Beckett himself was aware of this problem of recuperation, and dramatized and explored the necessity of living with the reversibility, not only of value, but of non-value into value, of diminished resources into increase.

Connor’s argument is incontrovertible, the more so because he sees Worstward Ho as finally exploring ways in which the doublebind in question might be resisted if not cancelled out. Rather than trying to wobble along the same tightrope, I’d suggest that another element also needs to be introduced into the equation which, if it does not allay the irony on which Connor insists, makes its bonds less harsh. The point is best demonstrated if we turn from money to that quintessential feature of the culture that surrounded the later Beckett, consumerism. No one who knows anything about Beckett would expect his writings to be crammed with references to consumer durables. In this respect, his work appears to occupy the opposite end of the aesthetic spectrum to, say, Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho – which, though it first appeared only two years after his death, belonged to a different world to Beckett’s, and is another token of the end of his era – thus expressing its austere elevation above historical particulars.

Yet, at the same time, many Beckett texts include a brand name or two. More strikingly still, the consumer items in question are often notably significant and even precious to the narrator or character concerned. In Waiting for Godot, for example, Pozzo is dismayed by the loss of his ‘Kapp and Peterson’ (CDW, p. 35). The reference is to a select manufacturer of tobacco pipes in Dublin, and has the interesting effect of making Pozzo seem much more clearly Irish than he does elsewhere. In Molloy, Moran congratulates himself ‘as usual on the resilience of my Wilton’ (TR, p. 109). Beckett clearly knew that Wilton carpets were supposed to last: they had long been associated with good wear and advertised accordingly. The Unnamable speaks of rubbing itself with ‘Elliman’s Embrocation’ (TR, p. 323), though this well-known contemporary remedy for a variety of physical aches and pains seems unlikely to be much use for some of its more outlandish afflictions, like lack of limbs. In Endgame, Clov supplies Nagg with a ‘Spratt’s medium’ (CDW, p. 97), thus treating him like an animal (since the reference is to a popular English dog biscuit) but also quite a classy one (since Spratt’s were originally associated with the English country gentry). Coinciden-tally, Spratt’s was playing out its own endgame at the time, and closed down not long after the play was first performed.

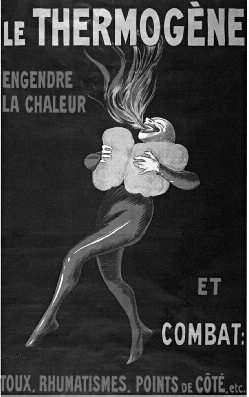

A pretension to class, or at least gentility, seems very much at stake in some of Beckett’s references to products. His narrators and characters often speak of the most humdrum consumables as if they were savouring exotic delicacies or lifting fine wines to the light. But other pretensions may also be on show. When Murphy and Ticklepenny contemplate the question of warming Murphy’s garret, for instance, the narrator behaves as though he has suddenly become a heating expert, interjecting that ‘It seems strange that neither of them thought of an oilstove, say a small Valor Perfection’ (MU, p. 94). The connoisseur and the specialist come together in Beckett’s choicest consumerist allusion: in Molloy, Moran promises himself ‘to procure a packet of thermogene wool, with the pretty demon on the outside’ (TR, p. 139). Thermogene wool was supposed to warm the body and cure coughs, rheumatisms, chest ailments and pains in the side. The reference to the demon places the product in question as specifically the French Le thermogène, not Beecham’s Thermogene Wool. Beckett’s taste is unerring: it was indeed a pretty demon, with very nice legs. The Thermogene demon was the invention of Leonetto Cappiello, whose innovative and often beautiful advertising posters were sufficiently well-known for him to have achieved canonical status by the 1940s.

Indeed, so pretty was Cappiello’s demon that it actually figured in not just one but two great post-war novels. George Perec’s Life: A User’s Manual refers to ‘boxes of thermogene wool with the fire-spitting devil drawn by Cappiello’.16 But this makes the image seem fiercer and less sexy. It also lacks the sense of Moran’s discernment. Beckett’s oddballs, tramps, vagabonds, destitutes and down-and-outs turn out to be remarkably pernickety about consumer goods. When they talk about them, they sound like fastidious aesthetes; this in striking contrast to their lack of discrimination in other spheres of their lives, whether gross or despairing. If products appear only rarely in Beckett’s works, his narrators and characters like to convey the impression that that is because they can take them or leave them. Beckett himself occasionally replicates this attitude with a loftiness that is all his own. In Molloy, for example, Moran and Gaber drink Wallenstein’s lager. This sounds plausible enough to be real, and Beckett’s German Diaries show a considerable knowledge of kinds of German beer. But these do not include Wallenstein; not surprisingly, because no such beer existed. Beckett got the name from Schiller’s (not very funny) trilogy Wallenstein, the first part of which is called Wallensteins Lager, meaning Wallenstein’s Camp.

Leonetto Cappiello’s ‘pretty demon’ in an advertisement for Thermogène wool.

Beckett’s insertions of consumer items are invariably playful. They sound a little like what (in the German Diaries) he called ‘precise placings of preposterous Tatsachen [facts]’.17 But the irony involved is by no means footling. On the one hand, the allusions suggest a limited but necessary resignation to the historical world in which he lived: after all, as Molloy so justly remarks, ‘you cannot go on buying the same thing forever … there are other needs, than that of rotting in peace’ (TR, p. 75). Indeed, he even goes so far as to consider combining meditational and commercial practices: ‘If I go on long enough calling that my life, I’ll end up by believing it. It’s the principle of advertising’ (TR, p. 53). This, of course, is as ludicrous an idea as the Unnamable’s momentary supposition that it might smother in ‘the crush and bustle of a bargain sale’ (TR, p. 294). In all three cases, nonetheless, the character’s ironical tone wryly acknowledges his historical situatedness. On the other hand, from Murphy onwards, even in the direst straits, Beckett’s characters display a reverse (or perverse) version of the aristocratic hauteur which, however impoverished, refuses to grant any significant status to the world of commerce. However profound one’s forlornness – or so the argument apparently goes – there are certain depths to which one does not sink.

Murphy quotes Arnold Geulincx: ‘Ubi nihil vales, ibi nihil velis’: ‘Where you are worth nothing, want nothing’ (MU, p. 101). From time to time, consumer items may come Beckett’s characters’ way, and please them. But his characters do not want them, in Geulincx’s sense. They do not hunger for them, or insatiably pursue them. ‘And things,’ asks the Unnamable, ‘what is the correct attitude to adopt towards things? And, to begin with, are they necessary?’ Strictly speaking, no: ‘if a thing turns up’, it tells itself, ‘for some reason or another, take it into consideration’. But finally, ‘People with things, people without things, things without people, what does it matter’ (TR, p. 294). When it’s there it’s there and when it’s not it’s not: Beckett knew very well that the culture of advanced capital was no more capable of expressing a whole than cash was likely to stay in the hand. The conviction of the contingency and historicity of that culture generates some robust shoulder-shrugging. Both he and his characters give the impression of being quite simply indifferent; indifferent to the imperatives of capitalism, indifferent to the politics that opposes it. This was equally the case in life and art. In his very last sentence, Molloy decides that ‘Molloy could stay, where he happened to be’ (TR, p. 91). Beckett clearly learnt this, too. He presents the culture of advanced capital as where he happens to be, like a wanderer who, one evening, finds he has strayed on to a not entirely featureless but not very interesting plateau.

This, however, is less true of Beckett’s writings in the eighties than it is of his earlier work. As Capital announced its imminent triumph, Beckett held it at an even greater distance. As it promised to fill every space and make every void substantial, his work ever more insistently emptied the world out, becoming more and more phantasmal and wraith-ridden. Where so many of the dominant discourses of the decade were raspingly ugly and assertive, Beckett’s work was poignantly shot through with strains of an exquisite, poignant gentleness, with ‘patience till the one true end of time and grief and self’ (CSP, p. 261). Ohio Impromptu (1981), Ill Seen Ill Said (1982), Nacht und Träume (1984), Stirrings Still (1988): these works brought to fruition an aspect of Beckett’s artistic practice beginning with ‘… but the clouds …’ (1976). They remain rooted in the familiar Beckettian profession of unknowing, as in the case of the figure in Stirrings Still,

resigned to not knowing where he was or how he got there or where he was going or how to get back or to whence he knew not how he came. (CSP, p. 263)

The tone, however, is subtly different to that of similar moments in earlier works. In Beckett’s last writings, not knowing becomes, not only an instance of the desolation of self, but also inextricable from sadness for others. He was partly fulfilling an obligation he had enjoined upon himself almost fifty years previously, when, in an entry in the German Diaries (GD, 4.1.37), he had exhorted himself to Zärtlichkeit not Leidenschaft, the use of tenderness, not passion.

Of course, none of this comes easy. But the note of compassion is the stronger for having to fight its way through other and more familiar Beckettian idioms. Thus, in Ill Seen Ill Said, the usual wrestle with language, the poverty of language, the insufficient poverty of language – ‘Resume the – what is the word? What the wrong word?’ – resolves itself by cracking open:

Riveted to some detail in the desert the eye fills with tears. Imagination at wit’s end spreads its sad wings … Tears. Last example the flagstone before her door that by dint by dint her little weight has grooved. Tears. (IS, p. 17)

‘And here he named the dear name’: Ohio Impromptu at the Barbican Pit, London, 2006.

At the same time, almost for the first time, serious images of comfort in suffering appear in Beckett’s work. In the wordless Nacht und Träume (a play for television), two hands appear, successively offering drink to a painfully solitary figure, wiping his brow and resting gently on his head, as though in benediction. Most hauntingly of all, Ohio Impromptu tells the story of a man who, having lost a ‘dear face’, quits the residence they had shared for another, then recognizes too late that he cannot return, since ‘Nothing he had ever done alone could ever be undone. By him alone’ (CDW, p. 446). In this extremity ‘his old terror of night’ lays hold on him. Then succour arrives:

One night as he sat trembling head in hands from head to foot a man appeared to him and said, I have been sent by – and here he named the dear name – to comfort you. Then drawing a worn volume from the pocket of his long black coat he sat and read till dawn. Then disappeared without a word. (CDW, p. 447)

As so often, Beckett speaks by piling up obstacles. Even the tone of this short passage is not immune to an insidious tonal ambivalence (particularly in the little play on ‘head in hands’ and ‘head to foot’). The mood of the play almost collapses under the weight of its distancing devices (the story is not enacted, but itself narrated by one figure to another. The listener repeatedly interrupts it with knocks on the table. The two figures have curious, identical appearances, with long black coats and long white hair). Nonetheless, an extraordinary consolatory language glints in the dark. Its power is inseparable from its melancholy:

So the sad tale a last time told they sat on as though turned to stone. Through the single window dawn shed no light. From the street no sound of reawakening. Or was it that buried in who knows what thoughts they paid no heed? To light of day. To sound of reawakening. What thoughts who knows. Thoughts, no, not thoughts. Profounds of mind. Buried in who knows what profounds of mind. Of mindlessness. Whither no light can reach. No sound. So sat on as though turned to stone. The sad tale a last time told. (CDW, p. 448)

Fleetingly, here and there, insistently if intermittently, the late Beckett breathes a new, secular life into a concept that, as his last works themselves tell us, has come to seem virtually inarticulable: misericordia.

It is hard to imagine references to the culture of consumption in Ohio Impromptu. But the attitude to possessions perceptible in Beckett’s late writings is nonetheless an extension or extreme version of his earlier attitude. Money and consumer items feature here and there in Beckett’s work, much as do animals, vegetables and philosophers, and are casually treasured or (on occasions) lightly passed over in the same way. This points in two directions. Even as Beckett settles for the world of advanced capital as where he ‘happens to be’, however minimally, whatever the moments of collusion, he also holds open another space for thought to those that characterized the dominant ideologies of his era. This is what Simon Critchley means when he writes of Beckett’s ‘weak messianic power’.18 Beckett is scrupulous, almost beyond comparison, in his repudiation of suspect positivities. He is adamantine in his refusal to conspire ‘with all extant meanness and finally with the destructive principle’ (to quote Adorno).19 He therefore chooses a via negativa. If ‘the task of thinking is to keep open the slightest difference between things as they are and things as they might otherwise be’, then that task is supremely exemplified in Beckett.20 As Connor says of Worstward Ho, Beckett will not surrender the idea of another sphere or possibility of value, however apparently absurd, minimal or purely negative its form. This negative space is the space of art; or rather, Beckett takes the preservation of the negative space to be integral to art’s task.

Thus a historical life of Beckett, even when it is as shrunkenly conceived as this one, logically requires an epilogue that turns its focus on historically specific forms of human life inside out. That is what my last little chapter tries to do.