This portrait, by William Williams and his apprentice, the soon-to-be-famous Benjamin West, depicted Lay in front of his cave but made no reference to his deep commitment to the cause of abolitionism.

This portrait, by William Williams and his apprentice, the soon-to-be-famous Benjamin West, depicted Lay in front of his cave but made no reference to his deep commitment to the cause of abolitionism.

These details of the Williams-West portrait show Lay’s distinctive appearance, his vegetarian habits, and his love of Thomas Tryon’s book The Way to Health, Long Life and Happiness, or, A Discourse of Temperance and the Particular Nature of all Things Requisit for the Life of Man (1683).

After the British parliament abolished the slave trade in 1808, Thomas Clarkson created this riverine genealogy of the triumphant antislavery movement, giving great credit to American Quakers. Clarkson labeled one of the tributaries in his map “Benjamin Lay.”

Lay lived in London and worked along the Thames as a sailor for a dozen years in the early 1700s.

Lay's wife, Sarah, also came from a maritime background, living in Deptford, England, site of the British Royal Navy’s first shipyard, where vessels such as the Cambridge were launched.

Two views of the Philadelphia waterfront, where Benjamin and Sarah arrived in 1732. Peter Cooper shows (above, 1720) Anthony Morris’s brewery at left (#4); below an artist named G. Wood provides a view across the Delaware River, 1735.

This image of a Quaker meeting, painted by an unknown artist most likely in the late eighteenth century, shows a man standing and addressing his fellow Quakers, men and women with covered heads, as the spirit of the “inward light” moved him. Lay thundered his denunciation of slavery at such meetings dozens of times.

The Quaker meetinghouse in Burlington, New Jersey, where Lay used a sword to pierce an animal bladder full of bright-red pokeberry juice, spattering the symbolic blood on the bodies of Quaker slave owners.

A book from Lay’s library by the English revolutionary William Dell, with a handwritten marginal comment about his past as a “common sailer.”

Benjamin Franklin was a friend of Lay and, in 1738, published his book, All Slave-Keepers That Keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates. Franklin himself had an ambivalent attitude about slavery, but later in life he took pride in having published Lay’s early, uncompromising attack on the institution and those who upheld it.

Benjamin Rush—Philadelphia physician, abolitionist, social reformer, and signer of the Declaration of Independence—was Lay’s first biographer. He wrote an admiring account of the life of the controversial antislavery activist in 1790, just as the abolitionist movement was gaining strength.

The oil portrait of Lay standing in front of his cave, commissioned by Benjamin and Deborah Franklin, c. 1758, was painted by William Williams (above) and Benjamin West (below) almost certainly without Lay’s permission.

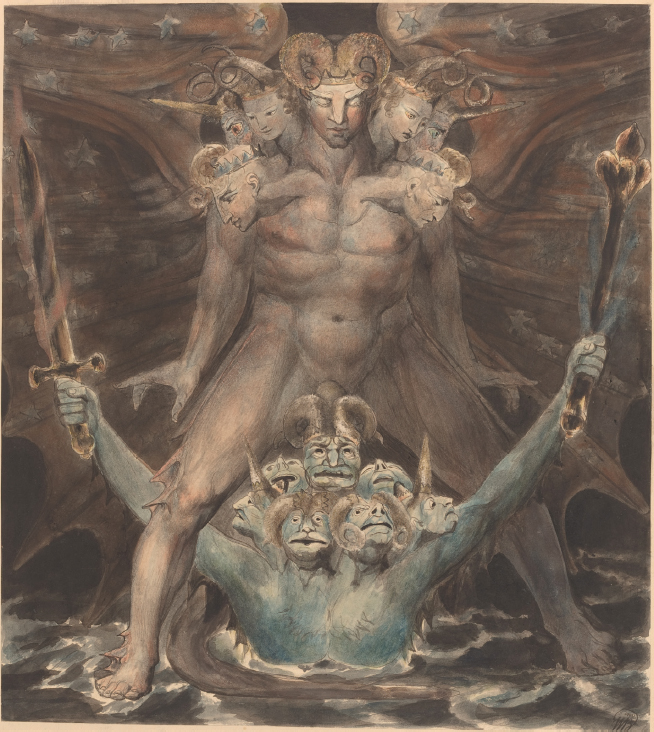

The great English poet and artist William Blake shared with Lay a fascination with the Book of Revelation. The “Great Red Dragon” depicted here represented the satanic forces of oppression militantly opposed by Lay and Blake.

Commissioned by Lay’s friends to create a memorial soon after his death, Henry Dawkins engraved this portrait, based on the Williams-West portrait, c. 1760. The print circulated widely among abolitionists on both sides of the Atlantic.