TWENTIES AND PHANTOMS

The motoring scene changed quite radically after the Great War ended. Sales of luxury models went into a decline, and at the same time the wealthy middle classes began to embrace car ownership. In recognition of this, Rolls-Royce embarked on a two-model policy, introducing a new and smaller model first alongside the existing and very grand 40/50.

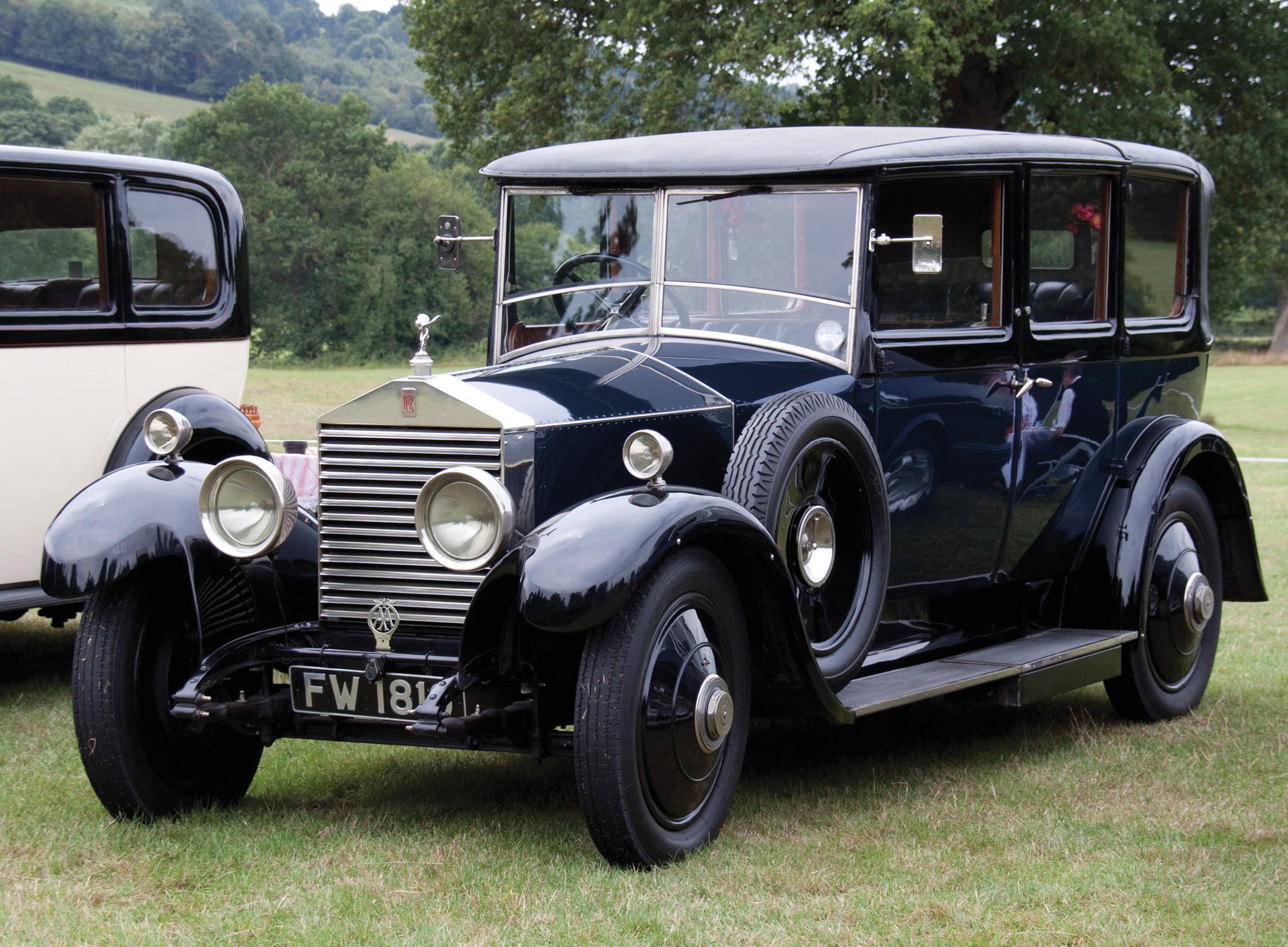

The Twenty was often burdened with quite heavy coachwork, and this drove Rolls-Royce to develop the more powerful 20/25 model. This is a 1928 example, with the horizontal radiator shutters typical of the Twenty and a Park Ward landaulette body.

This new model was called the Twenty and was a 20hp chassis aimed at the new breed of owner-driver. With a 3127cc engine that was under half the size of that in the 40/50, the car was also two feet shorter and weighed about half a ton less. It was an immediate success on its introduction in 1922, attracting a new breed of customer to the Rolls-Royce fold but maintaining the marque’s reputation for extremely high standards of reliability and refinement.

The bigger-bore engine in the 20/25 was an overhead-valve six-cylinder of 3669cc. It had a cast-iron cylinder block and head on an aluminium crankcase and delivered the power needed for the heavy bodies that customers so often specified.

Many owners came from the professional classes – doctors, lawyers and the like – and they tended to avoid flamboyant bodywork in favour of more discreet and conventional styles. Many of these bodies were heavy by their very nature, and so the ‘small’ Rolls-Royce earned a reputation for being rather slow. The change to a four-speed gearbox in 1925 helped acceleration a little, and four-wheel brakes arrived at the same time. Horizontal radiator shutters were a distinguishing feature of those built up to 1928. Just 2,940 of these cars were built before they were replaced in 1929, by which time they looked almost embarrassingly slow against cheaper alternatives.

The ‘small’ Rolls-Royce also attracted lighter and more sporting bodywork, of course, like the Special Touring Saloon body by Park Ward on this 1934 example.

So the engine was bored out to give more power, and the Twenty gave way in 1929 to the 20/25 model. This one went down very well, and sold more than twice as strongly as the contemporary ‘big’ Rolls-Royce, the Phantom I; a total of 3,827 were sold to make this the most popular Rolls-Royce model of the inter-war years. It was noted for exceptional flexibility on the top gear of its four-speed gearbox, for better brakes than its predecessor (thanks to an improved servo), and for its remarkably silent running. Late examples were capable of as much as 75mph, depending of course on the type of body fitted.

Gurney Nutting created some of the most attractive bodies on Rolls-Royce chassis in the 1930s, and this sedanca de ville style was available on both the 20/25 and the Phantom chassis, as well as on other makes.

There were some delightful bodies on the 20/25 chassis, by coachbuilders such as HJ Mulliner and Freestone & Webb, who were at the height of their powers in the early 1930s. Hooper built some attractive close-coupled saloons, and Gurney Nutting some sublime sedanca coupés. But this was also a time when the coachbuilding industry was flirting with streamlining, which sometimes compromised the lines for the sake of fashion. Many buyers of the 20/25 also turned for their bodywork to smaller and less skilled coachbuilders, whose products may have been more affordable but sometimes let down the quality of the chassis.

Highly regarded coachbuilder Thrupp & Maberley was responsible for the drophead coupé body on this 1934 20/25 chassis.

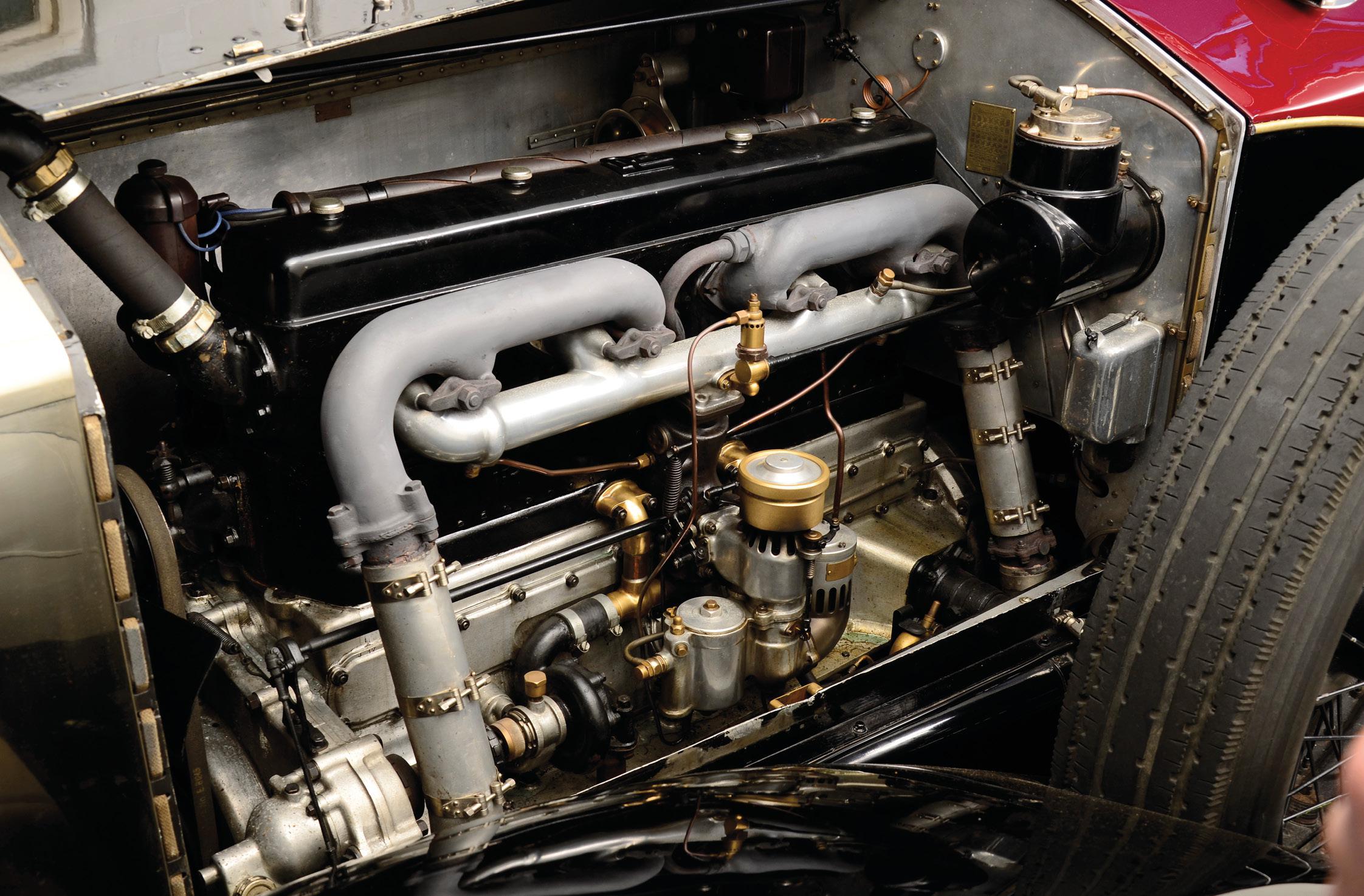

In the meantime, Royce had developed a replacement for the ageing 40/50 model. The new ‘large’ Rolls-Royce was introduced in 1925 with the name of Phantom, and in the early days was often described as the New Phantom. In practice, it turned out to be something of an interim design, because chassis, suspension, gearbox and brakes were more or less unchanged from the 40/50. What was new was the engine, now with modern overhead valves in place of the 40/50’s side valves, and with a longer stroke and narrower bore to reduce road tax liability under the RAC rating system that then obtained in Britain. Its capacity of 7668cc was also slightly greater than that of the 40/50.

Some customers had their chassis bodied by the best continental European coachbuilders, and this attractive cabriolet was by the Swiss master Graber, on a 1932 20/25.

The Phantom’s extra power was very welcome, but the downside was that the new chassis was much heavier than the old – by around 600lb. It still stood high off the ground on the cantilever springs of the 40/50, it had a taller radiator, and it entered production at a time when very large free-standing headlights were in vogue. All this did nothing for wind resistance, and Phantoms could rarely exceed 75–80mph, especially when fitted with the square-rigged formal bodywork that so many owners ordered. And many bodies were indeed rather dull, even though there were also some exotic creations for Indian princes in this period.

The ‘large’ Rolls-Royce was the Phantom from 1925, and this example bears the sporting drophead coupé bodywork that went so well with the chassis.

Phantoms were built at Springfield, too, adding 1,240 chassis to the 2,212 built at Derby. As some modifications were needed to create left-hand drive versions, their production did not begin until 1926, and the American chassis came with the benefit of a one-shot Bijur chassis lubrication system that Derby Phantoms did not have. By contrast with the British cars, the Springfield Phantoms often had very handsome coachwork, and some of the phaetons and town cars built by Brewster (still using their own name) were exceptional. Springfield chassis assembly ended in 1931, two years after that at Derby, although some chassis seem to have been built as late as 1933.

Now with nearly 7.7 litres, the six-cylinder engine of the Phantom boasted a modern overhead valve design, although the chassis was little changed from that of the 40/50.

Well aware of the Phantom’s performance shortcomings, Royce took care to redesign the large Rolls-Royce chassis comprehensively in the mid-1920s. In particular, he changed the suspension so that the cars sat lower to the ground – they were as much as 9 inches lower when formal closed bodies were fitted. The Phantom II was introduced in 1929 and was a very modern design that now incorporated the one-shot central lubrication system and could be had with short or long wheelbases. Although the engine was the same size as that of the older Phantom, it now boasted modern overhead valves and an efficient cross-flow cylinder head for greater power and performance. The gearbox, too, was now attached to the engine for the first time rather than mounted separately.

The short-coupled saloon body on this 1929 Phantom II chassis was built by Weymann, and has the fashionable faux-cabriolet look.

This athletic-looking short-chassis Phantom II Continental has a drophead coupé body by Freestone & Webb and dates from 1932. The car has a dickey seat, a rare feature on the Continentals.

The new low-slung chassis combined with the long bonnet gave the coachbuilders an ideal basis for their creations. The best of them delivered some beautiful coupés, sedancas and drophead coupés, but perhaps the most elegant were seen on the special Continental chassis that accounted for about 17 per cent of those built. This had taller gearing that allowed for more relaxed high-speed cruising, and was designed for exactly that on the long clear roads of the European continent. A maximum of more than 90mph was possible on late models, by which time engine power had been increased and the gearbox had been given synchromesh on all but bottom gear.

Sadly, the Phantom II was the last car that Royce himself would design. In 1933, he fell ill and died at West Wittering; he was seventy years old. Shortly afterwards, the double-R emblem on Rolls-Royce radiator grilles changed from red to black, and understandably this was long assumed to be a mark of respect or mourning. The reality, however, was more prosaic: the company had planned the change for some time, as the red had clashed with some of the more extravagant colours that customers were ordering in increasing numbers.

The Phantom II was also a natural choice for those who wanted a grand chauffeur-driven vehicle, and this is a sedanca de ville body by Park Ward on a 1930 chassis. It was delivered to an American lady when new.

Meanwhile, Rolls-Royce had been able to remove one of its competitors from the market, when it bought the ailing Bentley company in 1931. Bentley was a maker of high-quality chassis with a more sporting nature than those of Rolls-Royce, and the Phantom II Continental had been a nod in their direction. Most worrying to Rolls-Royce was the magnificent 8-litre model introduced in 1930, although the 4-litre derived from it in a hurry to compete with the 20/25 as financial trouble began to bite was less of a problem. Both these cars were removed from the market in 1931 (although a few lingered on unsold), but Rolls-Royce would use the Bentley name on a new and very successful range of sporting chassis from 1933.

HJ Mulliner built the elegant sedanca de ville body on this 1937 Phantom III. The chassis had its radiator over the front axle rather than behind, as on earlier Phantoms, giving a characteristic long-bonnet look.

Rolls-Royce, too, suffered from the effects of the Depression, and one result was that only 1,680 Phantom II chassis were sold before the model was replaced in 1935. Replaced it had to be, too, because developments by rival makers were making it uncompetitive. The early 1930s brought a rash of V12 engines from makers such as Packard in America and Hispano-Suiza in Europe, and even a V16 from Cadillac. As even medium-priced American cars began to appear with independent front suspension, the ride quality of the Phantom II lost its superiority.

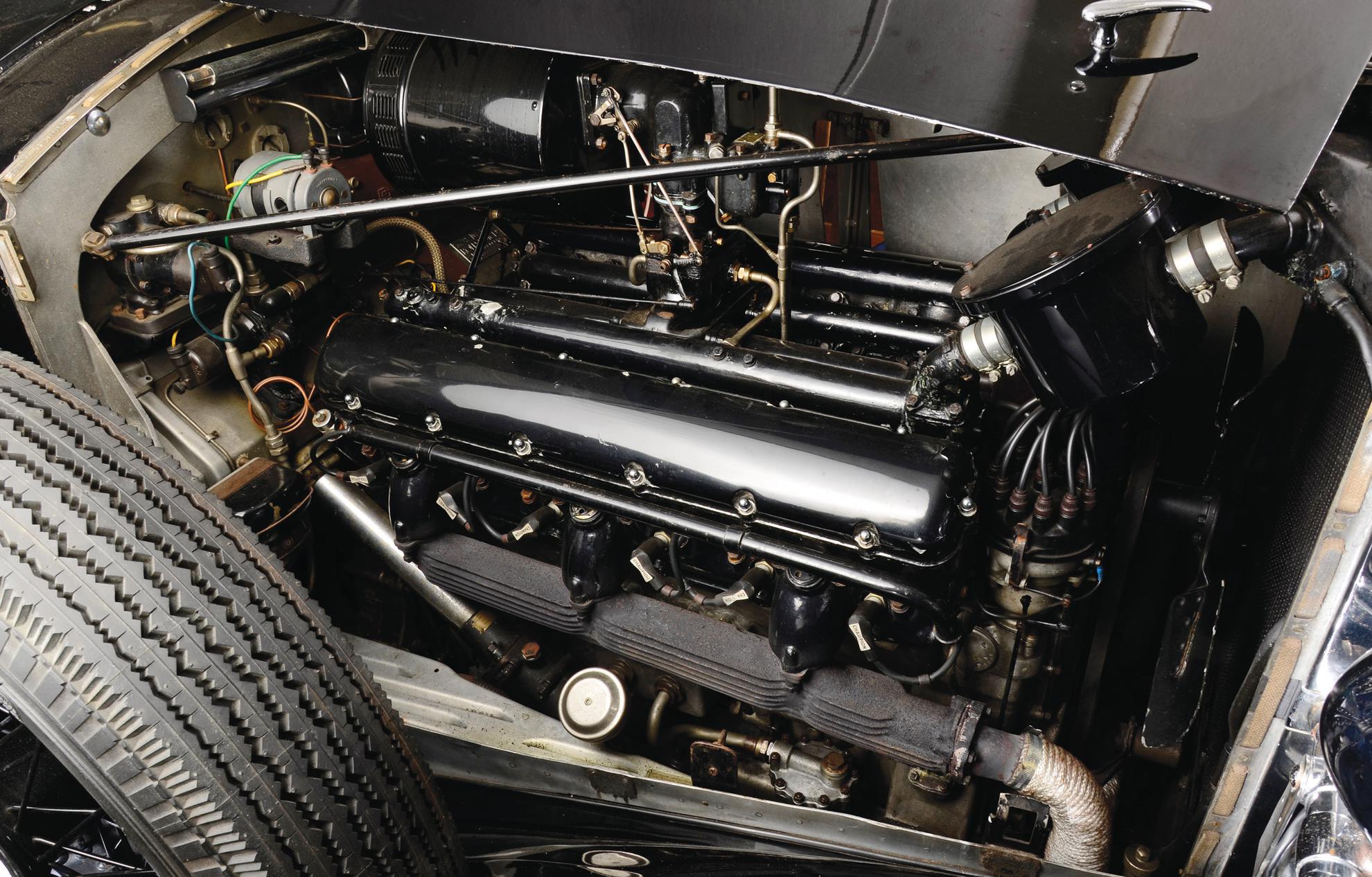

So when the replacement Phantom III was designed, it had a magnificent and complicated 7.3-litre V12 engine and a Rolls-Royce modified independent front suspension licensed from General Motors in the USA. The chassis was rigidly braced to allow the suspension to work at its best, the top three speeds in the gearbox had synchromesh, and there was a further improved central chassis lubrication system. Power was increased by 12 per cent over the Phantom II’s six-cylinder engine, and then again by a further 10 per cent later in production.

This was the magnificent V12 engine in the Phantom III. As always, the presentation mattered just as much as the performance and reliability.

A car this ambitious and complicated, and built to Rolls-Royce standards, was inevitably also formidably expensive. Its cost had two main results: first, many would-be owners shied away and chose the smaller Rolls-Royce instead; and second, very few owners bought such a chassis to have it fitted with frivolous or lightweight sporting bodywork. Most Phantom IIIs had deliberately grand (and therefore heavy) bodies, not all of them wholly successful. Changed front-end proportions, with the radiator now firmly ahead of the front wheels rather than above the axle centre-line, provided new challenges for the body designers. Just 727 of these superb machines were built before the outbreak of war in 1939 brought production to an end (although assembly in fact continued until orders had been fulfilled).

Luxury in the rear seat of a Phantom III – which was where most owners sat. Note the contemporary fashion for a pleated backrest combined with plain cushions.

The 25/30 chassis brought a larger engine, and this 1938 example was bodied as an elegant sports saloon by Hooper, which had held a Royal Warrant since 1830. The two-tone claret and black is very subtle, and cleverly lightens the car’s appearance.

The small Rolls-Royce was also updated in the middle of the decade, as the 20/25 model gave way to the more powerful 20/30. This car shared its new 4¼-litre engine with the sporting Bentley, although its chassis was essentially a longer-wheelbase version of that on the 20/25. Maximum speed and acceleration both benefited on cars with appropriately light bodywork, but a consequence of the Phantom III’s high cost was that many buyers had the heavy, formal coachwork they wanted built onto a 20/30 chassis instead. Yet there were some undeniably attractive creations on many of the 1,201 chassis built between 1936 and 1938.