Hunkapi (hoon-KAH-pee)

I Am Related to Everyone

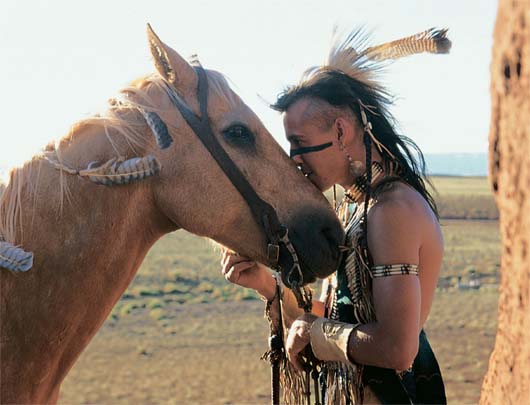

It is virtually impossible to understand horses from a Native American perspective without first understanding how Natives view their relationship to all animals.

Sometime after the mid-sixteenth century, a growing number of people in North America were introduced to two notions. These two notions were that humans and nature are not related, and that humans hold the highest position on earth according to Creator’s ladder. We Native Americans know this idea was brought to the New World by the Europeans.

Prior to this way of thinking, Native Americans viewed themselves as an integral part of nature, having an equal share—along with everything else in the universe—of the earth. Although Native Americans believed that they were charged with the stewardship of the earth and its animals, they did not believe that they were to rule, subdue, or preside over it.

ANIMALS ON THE MOST FUNDAMENTAL LEVEL ARE EITHER HUNTER OR HUNTED. THIS FACT, MORE THAN ANY OTHER SINGLE CHARACTERISTIC, DETERMINES THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN species, human beings included. If we are to develop a healthy working relationship with an animal, we must first understand how that animal views us. If the animal in question views us as a hunter, its natural fear and apprehension must be overcome for it to exhibit trust toward us. If the animal views us as hunted, there is a certain amount of respect we must earn before a relationship can be established.

Horses are hunted—humans are hunters. Humans look like hunters, act like hunters, move like hunters, sound like hunters, and even smell like hunters. Now imagine you are a rabbit. Along comes a wolf who wants to gain your trust. You know very well that wolves eat rabbits, and initially you avoid the wolf. Yet this wolf seems sincere in his efforts to build a relationship with you. The apprehension you would feel in that situation is the same apprehension your horse feels until he trusts you.

From your horse’s point of view, you could have him for dinner at any given moment. If you have ever become angry or frustrated with your horse and perhaps yelled or snapped, you may have witnessed your horse shifting his weight to his hindquarters, lifting his chin, looking down at you with fearful eyes, and trying to turn or back out of the situation. In that moment, your horse has exhibited his nature as a hunted animal.

Abenaki, Northeast Woodland

LONG AGO, GLUSCABI DECIDED HE WOULD DO SOME hunting. He took his bow and arrows and went into the woods. But all the animals saw him coming and hid from him.

Gluscabi could not find them. He was not pleased. He went home to the little lodge near the big water where he lived with Grandmother Woodchuck.

“Grandmother,” he said, “make a game bag for me.” So Grandmother Woodchuck took caribou hair and made him a game bag. She wove it together tight and strong, and it was a fine game bag. But when she gave it to Gluscabi, he threw it down.

“This is not good enough, Grandmother,” he said. So she used moose hair and wove him another game bag, large and strong. She flattened porcupine quills with her teeth and she wove a design into the game bag to make it even more attractive.

But Gluscabi threw it down. “Grandmother,” he said, “this is not good enough.”

“Eh, Gluscabi,” said Grandmother Woodchuck, “how can I please you? What kind of game bag do you want?” Gluscabi smiled. “Ah, Grandmother,” he said, “make one out of woodchuck hair.”

So Grandmother Woodchuck pulled all of the hair from her belly. (To this day, woodchucks have no hair there.) She wove it into a magic game bag. No matter how much was put into it, there was still room for more.

Gluscabi smiled. “Oleohneh, Grandmother,” he said. “I thank you.” He went back into the woods and came to a large clearing. He called out as loudly as he could, “All you animals, listen to me. A terrible thing is going to happen. The sun is going to go out. The world is going to end, and everything is going to be destroyed.”

The animals became frightened. They came to the clearing. “Gluscabi,” they said, “what can we do? The world is going to be destroyed. How can we survive?”

Gluscabi smiled. “My friends,” he said, “just climb into my game bag. You will be safe in there when the world is destroyed.”

So all the animals went into his game bag. The rabbits and the squirrels went in, and the game bag stretched to hold them. The raccoons and the foxes went in, and the game bag stretched larger still. The deer and the caribou went in. The bears went in and the moose went in, and the game bag stretched to hold them all. Soon, all the animals in the world were in the bag. Gluscabi tied the top of the game bag, laughed, and slung it over his shoulder and went home.

“Grandmother,” he said, “now we no longer have to look for food. Whenever we want anything to eat, we can just reach into my game bag.”

Grandmother Woodchuck opened Gluscabi’s game bag and looked inside. There were all the game animals in the world. “Oh, Gluscabi,” she said, “you cannot keep all these animals in a bag. They will sicken and die. There will be none left for our children and our children’s children. It is right that it should be difficult to hunt them. It makes you stronger by trying to find them, and the animals grow stronger and wiser trying to avoid being caught. This is the right balance.”

“Kaamoji, Grandmother,” said Gluscabi, “that is so.” So he picked up his game bag and went back to the clearing. He opened it up. “All you animals,” he called out, “you can come out now. Everything is all right. The world was destroyed, but I put it back together again.”

All the animals came out of the magic game bag. They went back into the woods, and they are still there today because Gluscabi heard what his Grandmother Woodchuck had to say.

One would think that it would be easier to establish a relationship with a hunted animal. Trust is easily gained in prey animals simply by letting the animals know we are not going to harm them. There is another hurdle we must overcome with the hunted animal.

Many hunted animals are also herd animals and spend most of their lives defending their position within the herd. Behavior of a herd animal, especially an animal who is in a position to reprimand, can easily be confused by humans as predator behavior. Vicious attacks, including biting, kicking, chasing, and stomping, occur often. In the herd, an ongoing pecking order is enforced and reinforced. It is the herd members’ responsibility to constantly challenge the leadership abilities of other herd members with higher rank. This constant insubordination insures that the most qualified are given the higher positions in the herd.

Along comes the human.

In an attempt to develop a relationship with a hunted herd animal such as the horse, the human must not only give the animal a reason to feel secure, but must maintain the status of leader, alpha, or itancan, in the herd—a herd of two, rider and horse. This can become tricky, and the scales are not balanced in the human’s favor.

If you have ever felt while training or riding that your horse is getting the better of you, acting spoiled, or just not paying attention, you are probably losing your status as itancan of your two-member herd. This behavior is usually nothing more than your horse getting comfortable with, and enjoying, his new status.

In the very beginning of relationship development, it is important for you to be the leader your horse is looking for. When you and your horse are standing in a training arena, your horse will usually first exhibit his leadership qualities by walking or trotting, high headed, around you. When you do not follow as he expects you to, he may begin to question his own position in the herd. He will begin to pay more attention to you by pivoting an ear toward you, looking at you, or possibly turning to face you. At this moment, take the leadership position by physically putting yourself in a position of leadership. Walk in front of your horse expecting him to follow, and he will.

Cherokee, North Carolina

BACK WHEN THE WORLD WAS YOUNG, THE HUMANS AND the animal people could speak to each other. At first they lived in peace. The humans hunted the animals only when they needed food or skins to make clothing. Then the humans discovered the bow and arrow. With this new weapon, they could kill many animals quickly and with great ease. They began to kill animals when they did not need them for food or clothing. It seemed as if all the animals in the world would soon be exterminated.

The animals met in council. The bears decided they would have to fight back. “How can we do that?” said one of the bear warriors. “The humans will shoot us with their arrows before we come close to them.” Old Bear, their chief, agreed. “That is true,” he said. “We must learn how to use the same weapons they use.” The bears made a very strong bow and fashioned arrows for it. But whenever they tried to use the bow, their long claws got in the way. “I will cut off my claws,” said one of the bear warriors. He did so, and he was able to use the bow and arrow. His aim was good and he hit his mark every time.

“That is good,” said Old Bear. “Now can you climb this tree?” The bear tried to climb the tree, but he failed. Old Bear shook his head. “This will not do. Without our claws, we cannot climb trees or hunt or dig for food. We must give up this idea of using the same weapons the humans use.”

One by one, each of the animal groups met. One by one, they came to no conclusion. It seemed there was no way to fight back. But the last group to meet were the deer. Awi Usdi, Little Deer, was their leader. “I see what we must do,” he said. “We cannot stop the humans from hunting animals. That is the way it was meant to be. However, the humans are not doing things in the right way. If they do not respect us and hunt us when there is no real need, they may kill us all. I shall go now and tell the hunters what they must do. Whenever they wish to kill a deer, they must prepare a ceremony. They must ask me for permission to kill one of us. After they kill a deer, they must show respect to its spirit and ask for pardon. If they do not do this, I shall track them down, and with my magic I will make their limbs crippled. Then they will no longer be able to walk or shoot a bow and arrow.”

Awi Usdi, Little Deer, did as he said. At night, he whispered into the ears of the hunters, telling them what they must do. When they awoke, some of the hunters thought they had been dreaming and they were not sure that the dream was a true one. Others, though, realized that Awi Usdi, Little Deer, had spoken to them. They did as he told them. They hunted for the deer and other animals only when they needed food and clothing. They remembered to prepare in a ceremonial way, to ask permission before killing an animal, and to ask pardon when an animal was killed.

The others continued to kill animals for no reason. Awi Usdi, Little Deer, came to them and, using his magic, crippled them with rheumatism. Before long, all of the hunters began to treat the animals with respect and followed Awi Usdi, Little Deer’s, teachings.

So it is that the animals have survived to this day. Because of Awi Usdi, Little Deer, the Indian people show respect. To this day, even though the animals and people no longer can speak to each other as in the old days, the people still show respect and give thanks to the animals they must hunt.

Through oral tradition, wisdom among Native Americans was a cumulative process. Wisdom of the elders was passed down to the next generation so that it could be added to the experiences of those people. Native American wisdom about animals and our relationship to them was above and beyond that of many cultures. From this wisdom we can learn many things.

Beyond hunter-hunted relationships are complex understandings that are made clear by the Native American view of animals. All animals, living on, in, or above Mother Earth, have always been viewed by Native Americans as brothers and sisters. The words “brothers and sisters” are used here in a very literal sense and should not be confused as esoteric niceties. Animals were viewed, treated, and respected by Native Americans in the same way as they treated their genetic brothers and sisters.

The brothers and sisters of the animal kingdom were viewed by most tribal members in one of three ways—as guides, companions, or creatures needing protection. Just as you would respect and seek guidance from an older sibling or relative, so did most Native tribes seek wisdom from animals viewed as guides. The friendship found in a relative of like age is the same friendship found in animals viewed as companions. The responsibility felt toward a younger sibling is the same as the sense of responsibility for providing shelter to those species called the ones to be protected.

If you have ever experienced a long-term relationship with a dog, cat, horse, or other animal, you probably know the brotherly love and rapport that accompanies this relationship. Native Americans see all living things with the same intensity as you see your special pet. Every bird, fish, rock, or plant is given the same respect and admiration as you would give a very close family member. This philosophy was commonplace and taken for granted—an understanding that supported the core beliefs of the indigenous peoples in North America.

Although horses were viewed by Native Americans as companions and animals to be cared for, more often than not the horse was more of a messenger, teacher, or guide than it was a student. Too often, modern-day riders view their animals as students and can’t seem to understand why those animals don’t “get it,” when in fact, their horses already know it. Believe it or not, many horse owners have said, “my horse does not know how to go right,” or “my horse won’t stop.”Think about these statements for a moment. Horses know how to do everything that is possible for them to do from the day that they are born. It is the rider who has the deficiency in communicating requests. Horses do not need to be taught how to stop, turn, or spin around in a circle. Riders must be taught how to communicate these requests to their horses in an understandable way.

Native American riders, who only had access to horses for one hundred fifty to two hundred years, did one thing better than most, thereby becoming the greatest horsemen this continent has ever seen—they viewed their horses as guides and they listened to their horses.

Among many of the tribes and Nations there is a common custom that trains an individual from a young age to listen. This custom takes on different forms in different tribes, but it is exemplified by what’s called the talking stick, a short stick of twelve to eighteen inches, usually decorated with carvings. The person holding the stick is the only person permitted to talk. Once that person has finished, the stick is passed to the next person to talk. In the unlikely event that someone should interrupt the person holding the stick, the speaker would point at the violator. The embarrassment associated with this infraction was usually enough to make the offender get up and leave the room.

It is said that the reason Creator gave two-leggeds two ears and one mouth was so that we could listen twice as much as we talk. Start listening.

Listen! Or your tongue will make you deaf.

—CHEROKEE SAYING

Nioeye Weksuye [nee-OH-yay week-soo-yay]

YOUR WORDS I WILL REMEMBER

There is only one thing that stands between a horse and a rider performing as one creature. Only one hurdle separates the perfect combination of two-and four-legged. One stumbling block awaiting the horse and rider who wish to act as one. It is communication. A horse and rider who can communicate successfully can do anything. Anything!

Many people are awed at the things that great trainers can do with their horses. One Mexican charro can make his horse lie down and stay down for over five minutes without ever touching the horse. Some horses can make hairpin turns at breakneck speed around barrels. Reining horses slide over twenty feet on packed soil to a stop. Some horses can jump over fences that are over seven feet tall.

Great trainers are great communicators. Horses know how to jump. They know how to stop, run, turn, sidepass, piaffe, go backward, and lie down. If a horse knows how to stop, and if you want the horse to stop, all you have to do is effectively communicate this. The horse will stop (considering that pain or fear is not involved) only if a healthy working relationship has been established between horse and rider.

Modern riders use a variety of training methods that aren’t always the best way of communicating with a horse. Two popular methods are “telling” and “asking.”

Telling is the most widespread way riders communicate to their horses. Most of us have been conditioned to understand that telling is what animals understand best. We say sit, stay, giddyap, whoa, roll over, come, heel, back up. This is the way most people train their animals; they tell them what to do and expect them to obey. When you do what you are told, you are rewarded. When you disobey, you are punished. Within this situation, there is no room for opinion, judgment, intuition, expression, or instinct. You are merely performing a task because someone is telling you to do it. How do you feel when you are around someone who is always telling you what to do?

The problem with telling as communication is that the only two options given for performance are reward and punishment. The reward is not necessarily something you want, but rather something the teller wishes to give you. The negative support of punishment is nothing more than do this or you will suffer in some way. Have you ever raised your hand in anger as if you were about to hit your horse? You may find that in the future just the raising of your hand will cause a shying away.

Horses have incredible memories. If intelligence were purely graded on the ability to recall and utilize information, I believe horses would be considered far more intelligent than humans. It is very important to be aware of the memory power of the horse when training, especially when communicating your requests.

More often than not, the reward for obedience is nothing more than not being punished. For example, you kick your horse to get him moving. If your horse begins to walk, the reward is that life goes on without reprimand. If your horse does not begin to walk, he gets kicked harder. In effect, the only reason your horse moves at all is to avoid being kicked more severely.

Telling does not make for a very good relationship with your horse. As a matter of fact, it makes for no type of relationship whatsoever.

Asking has its place in communication, but asking can be a trap. Although asking is a nice way to try to get your horse to do something, most riders, unfortunately, ask in the wrong way and for the wrong reasons. The asking technique is used primarily in two situations both of which are usually ineffective.

In one situation, you are very attached to your horse or view your horse as a pet much like a house cat. You believe that because you and the horse are such good friends, a mere verbal request will result in the horse doing what you ask. Because the horse does not understand the human language, and because you may not know what the horse does comprehend, your efforts are futile at best. Although this asking technique is well intentioned, horses need more than just a cosmic connection with their riders to understand what is being asked.

The other situation is the when-all-else-fails exercise. It goes something like this. You nudge your horse’s sides with your heel and your horse doesn’t respond. You then give the horse a good stiff kick in the ribs (the telling method of communication). Still, your horse stands and up goes the head. You then decide that in order to get this animal moving, you must convey the message more intensely. By lifting your boot, you are able to land a good solid jab to the horse’s side. You probably end up on the ground as the dust settles. You climb back onto the horse’s back realizing that a new technique must be utilized. After a few deep breaths, you begin the when-all-else-fails asking technique. Giddyap girl? Come on!? You can do it!? Giddyap!? Walk? Pleeeeeeease?? Your horse has a good chuckle at your expense.

The “wishing” and “hoping” techniques are offshoots of the asking technique. Asking your horse nicely, even with the best intentions, cannot be relied on to produce results. A relationship must exist and you must know how to communicate effectively with your horse.

You must so that your words may go as sunlight speak straight to our hearts.

—COCHISE, CHIRICAHUA APACHE

Itancan [ee-TAHN-chun] and Waunca [wah-OON-chah]

LEADER AND IMITATOR

Native American riders knew the nature of the medicine dog. Most of the horse’s nature stems from the horse being a herd animal. In a herd, the itancan leads and all other members of the herd follow. The herd knows their itancan has their best interests in mind. You are the itancan of your two-member herd. It is only natural that your horse will follow your lead for he knows you have his best interests in mind.

It is important you understand the psychology behind waunca. It is the responsibility of waunca to follow itancan without regard to the outcome of itancan’s actions. If waunca did not blindly follow itancan, the purpose of the herd would be defeated and eventually the species would die out.

There is a lot more than most people realize to the saying “you can lead a horse to water but you can’t make him drink.” It is possible, though, to lead a horse to drink. When a herd of horses approaches a watering hole, the itancan always approaches the water in front of the herd. The itancan checks for danger and then takes a few sips. Only then will the rest of the herd take its fill, as the itancan backs off and watches for predators. After the herd has finished drinking and the itancan feels all is safe, then—and only then—will he go back to the water and drink until his thirst is quenched. The itancan has led horses to water and led them to drink.

By being the itancan of your herd, you can achieve the same result in any number of training exercises. Once you are established as the itancan, your horse will always look to you for guidance and direction.

Iyuptala [ee-yoo-P’TAH-lah]

ONE WITH

Being “one with” was integral to Native American life. Life was lived in the understanding that the people were one with their environment. They were one with Mother Earth. They were one with the elements, and, above all, one with Creator. So basic was this way of being in the world that certain words such as trust, integrity, belief, faith, and promise simply did not exist. The concepts behind them were meaningless. As every action reflected the Native American’s total trust in the environment, a breech in that trust was regarded as unthinkable. Trust and integrity were not the exception but the rule.

Native Americans exhibited the same type of trust that was shown to them by natural things. Never will you touch a fire that will not burn you. Never will you see rain that is not wet, and never will you see a wolf who is really a sheep. Natural things do not lie.

The type of trust that is exhibited by natural things is entirely different from human trust. We must understand both types of trust before we embark on a relationship with our horses.

Unfortunately, the experience of being “one with” has been lost by the majority of people living in the twentieth century. Far from feeling at one with our environment, one with Mother Earth, or even one with Creator, we learn from a very young age to trust nothing that has not first earned our trust. Most animals, on the other hand, are born with the understanding to trust everything until there is a reason not to trust. Native Americans learned to trust in the “animal” way. Once they were given very good reasons not to trust, it was too late.

In May of 1966, an expedition to the Galápagos Islands revealed evidence that animals trust humans until they are given a reason not to. Scientists were amazed at how the animals of the islands showed no intimidation to their presence. Birds landed on their shoulders, and the scientists could sunbathe alongside the sea lions. Any species, even those with young, could be approached without difficulty. It was not until the scientists began collecting, tagging, and trapping the animals that their behavior changed dramatically. After the animals were given a reason not to trust, they began treating humans as predators rather than cohabitants.

The scientists on that expedition discovered that the apprehension shown to them after they had breached trust was not hereditary. A newborn animal’s tendency to flee from a human is not due to its ancestry or genes, but to observing its parents fleeing. Newborn animals found away from their parents could be approached, touched, and held. They exhibited trusting behavior toward the scientists.

Another example of this natural trust is evident in the relationships turtles have with most animals. Most turtles and tortoises have managed somehow to retain the trust of much of the animal kingdom. Because they have never breached this trust, they are generally treated with indifference. If for some reason turtles and tortoises across the globe started biting the toes and legs and fins of passers-by, the animal kingdom’s attitude toward turtles and tortoises would change. Animals exhibiting predator behavior, in this case the turtles and tortoises, experience an immediate and violent response to their behavior.

The horse, when weighed on a trust scale (if there were such a thing), would fall somewhere between a dog and cow. Most horses are very trusting, yet it does not take much for them to lose that trust. This concept must be in the forefront of your mind whenever you are in the presence of your horse.

Your horse’s trust in you can be lost in any number of ways. Lose your temper and hit your horse on the head, and you are well on your way to creating a head-shy horse who will not trust you to touch his head again. Trust can be lost when you load your horse into an unsafe trailer with a jagged piece of metal on which he cuts his leg. It can be lost when your horse strains a tendon after you’ve urged him down a hill he is not able to safely or confidently negotiate. In each of these examples, the trust between horse and rider was breached by the rider.

Remember, you are the itancan. You have chosen and earned that title with the stipulation that you will lead the herd safely. If you begin to breach that trust by not acting responsibly and in the itancan manner, you will be replaced. Who will replace you? The other member of your herd, your horse.

To understand what it means to be “one with,” reflect for a moment on an eagle soaring with the currents. The eagle does not glide on top of or below or alongside those currents, but is actually enveloped within them. Every shift in the wind affects the eagle and every beat of the eagle’s wings moves the currents around him. Every move that one makes affects the other. The eagle becomes a small part of the winds. His movements reflect the movements of the ever shifting winds of which he has become a part. The soaring eagle knows what it means to be one with the wind.