The front of Indian Rock showing a plaque placed on the boulder in 1933. Author’s collection .

2

THE FOUNDING OF WINDHAM

THE NATIVE AMERICANS

The earliest inhabitants of Windham were Native Americans belonging to the Penacook tribe, commonly known as the Pawtuckets. While it is unknown how early the area was inhabited, it was certainly centuries before the first Europeans arrived. The earliest recorded interaction between Europeans and the local Pawtuckets occurred around 1653, when missionaries—namely, John Eliot—preached at the Pawtucket Falls in Lowell, Massachusetts. However, the importance of Pawtucket Falls in Windham’s Native American history reaches far beyond interactions with Christian missionaries. The falls, located a convenient twelve miles from Windham, were a valuable source of fish. It is recorded that up until 1818, when the water from the falls was redirected for Lowell’s burgeoning factories, the roar of the falls and rushing waters below could easily be heard in Windham.

The Pawtucket in Windham certainly camped along the shores of Cobbett’s Pond and Canobie Lake, as numerous arrowheads and Native American artifacts have been found over the last century at both locations. Such artifacts include the stone tools handcrafted by tribesmen for various uses, such as skinning animals. Arguably, the most prominent of the Pawtucket relics in town is Indian Rock. Located just a short distance from the north shore of Cobbett’s Pond, the large boulder stands around five feet high and is several feet wide. It is surrounded by several slightly smaller boulders, none of which bears any evidence of use by the Pawtucket tribe. On the top are several circular holes a few inches deep and several inches in diameter that were, at one time, used by the Native Americans for pounding corn and other grains. Those interested in the early history of Windham can still visit this rock, which is marked by a plaque placed on the front of the boulder in 1933. Windham is also home to another unusual Native American site, aptly named Deer Ledge; the Pawtuckets once chased a deer over the ledge, into the waters of Rock Pond below.

In the mid-seventeenth century, the tribe was headed by its last great chief, Passaconnaway. In the 1660s, Passaconnaway, at the advanced age of somewhere between 90 and 110 years old, believed he did not have many years of life left. A feast and dance were held, at which he warned his people to be peaceful with the Europeans, as this would be the only way to ensure the survival of the tribe. The tribe heeded his warning and had little contact with the Europeans of southern New Hampshire. The Pawtuckets did not remain in Windham long after Passaconnaway’s death around 1679. They relocated the headquarters of the tribe to Concord, New Hampshire, several years following the chief’s passing. However, for the next fifty years, the Pawtucket tribe continued to travel to Pawtucket Falls, undoubtedly traveling through the primitive settlement at Nutfield, which encompassed the modern towns of Londonderry, Derry and Windham and, to a lesser extent, portions of Hudson, Manchester and Salem.

The front of Indian Rock showing a plaque placed on the boulder in 1933. Author’s collection .

One of the only recorded interactions between the Pawtuckets and the settlers of Nutfield occurred in a tragic way in 1721. Just a couple years after the Scotch-Irish arrived in Nutfield, a party of men was traveling from Haverhill, Massachusetts, to the home of Daniel Gregg. On the way, the men spotted a small site near some rocks that would serve as an ideal location to stop and rest before continuing to their destination. After lighting a fire and eating their dinner, they continued on. In time, they realized they had forgotten something at the camp, though there is no record that indicates exactly what was left at their makeshift campsite. A young boy who was traveling with the group was sent back to retrieve it, but he would never again see his fellow travelers. When the boy had not returned to the group within a reasonable time, the men went back to the location they had camped and found his body. The boy had been killed by a member of the Pawtucket tribe on the banks of Golden Brook near the home of James Noyes. The boy’s body was buried on the banks of the brook with no marker to denote the place of the first death and burial in Windham.

Eventually, the tribe completely removed to Canada, leaving little trace of their existence in Windham. Only a few of the earliest settlers were aware of their presence. Leonard A. Morrison concluded his writing on the Native Americans in town with a poem, which is as fitting in his work as it is in this one:

I will go to my tent and lie down in despair,

I will paint me with black and sever my hair;

I will sit on the shore when the hurricane blows,

And reveal to the God of the tempest my woes.

I will weep for a season, on bitterness fed,

For my kindred are gone to the mounds of the dead.

THE SCOTCH -IRISH ARRIVE IN NUTFIELD

The earliest settlers of Nutfield were driven to the New World by the unrest in seventeenth-century Ireland. Many of those who left Ireland for America in 1718 were survivors of the 1689 siege of Londonderry. The siege on the walled city began shortly after King James II of England was deposed by his daughter and son-in-law, William. James fled to France, hoping to gain support in order to try to gain control of Ireland and eventually take back the throne in England. With aid he received from the French, James’s forces were able to capture Dublin, as well as the surrounding region. This forced many of the British supporters to flee to the north, with some going to the city of Londonderry. Those in the fortified city would prove to be the most formidable opponents James had ever, or would ever, face.

On April 20, 1689, James began his bombardment of the city; many lives were lost and countless buildings were destroyed by the resulting fires. James’s forces also blockaded any routes by which the city might receive supplies, leaving the survivors of the first attacks without the food needed to survive more than a couple months. Still, the people of Londonderry steadfastly refused to surrender. A clergyman of the town, George Walker, would routinely give strong sermons that instilled in the listeners enough courage and strength to continue their fight even as conditions worsened. Horse meat became a highly desired commodity, and when the meat ran out, even the hides of horses were consumed. When all the edible parts of the town’s horses, including the blood, had been consumed, the townspeople were forced to eat any remaining small animals, including dogs, rats, mice and cats.

Months passed, and the food supply had been diminished to just one pint of food per person. It was estimated that most individuals would be able to survive for only another two days with the supplies on hand. Despite the circumstances, those still alive refused to surrender. After 103 days under siege, the British finally managed to break through the blockades and bring much-needed supplies to Londonderry. With more strength than ever to fight to hold the city, Londonderry was held by British supporters until July 31, when the enemy finally withdrew, without much of a fight. Just under a year later, the armies of James were finally defeated by William, his successor.

The government of England felt that the heroic acts of the people of Londonderry were so important to the nation that all who fought in the siege were exempted from taxation. When a group of these people came to Nutfield seeking religious freedom, they were given the same tax-exempt status until the American Revolution. Along with these men came families and other members of their community, all led by Reverend James MacGregor. When the group reached America in 1718, some chose to settle in the Casco Bay area while others went to such towns as Andover and Dracut, Massachusetts. By April 13, 1719, a group of the immigrants had arrived in Haverhill, where they heard of an unsettled tract of land referred to as “Chestnut Country”; the name was derived from the abundance of chestnut trees in the area. Thus, the land was christened Nutfield by the first settlers.

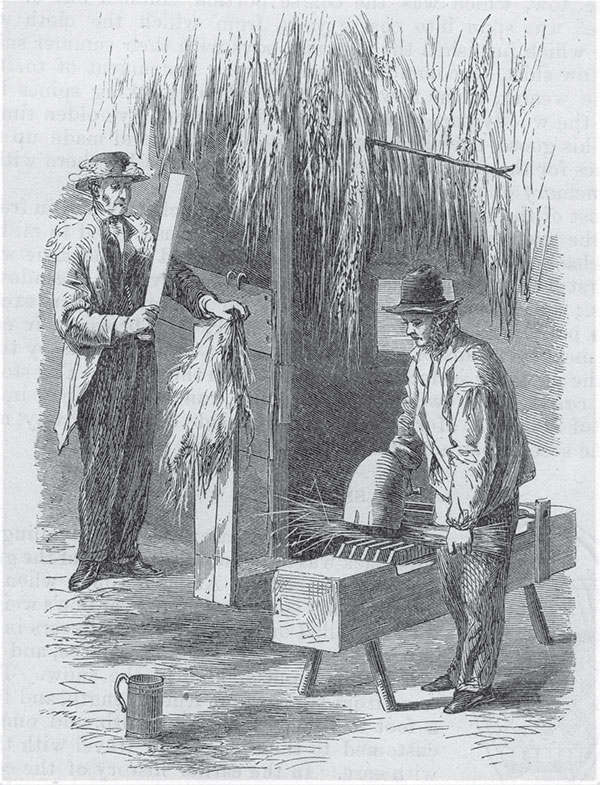

A nineteenth-century engraving depicting how early settlers would have processed their flax into linen. From History of Windham in New Hampshire (Rockingham County), 1719–1883.

A nineteenth-century engraving depicting an early eighteenth-century home scene similar to what would have been found in the homes of early settlers. From History of Windham in New Hampshire (Rockingham County), 1719–1883.

Many of the men of the group left their families in order to make their way to Nutfield to see if it would be suitable for a small community. Finding promise in the land, they received a grant for twelve square miles from the royal governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. After building a few temporary huts, the men returned to Haverhill to bring their families and possessions back to Nutfield. The party stopped in Dracut allowing Reverend MacGregor to join them; the entire group arrived in Nutfield on April 22, 1719.

Although the community started small, it grew to include seventy families within the first five months. One month later, it had grown to around 105 families. The rapid growth of the settlement necessitated the incorporation of Nutfield as a town, but it would be almost three years before Londonderry was finally incorporated on June 21, 1722. The town continued to grow, and running a town of that size eventually became cumbersome. Such was at least part of the reason why Windham split from Londonderry and was incorporated on February 23, 1742, by Governor Benning Wentworth.

REVEREND THOMAS COBBET

Thomas Cobbet was born in Newbury, England, in 1608 to a financially poor family. He studied at Oxford as a young man but decided to immigrate to America to alleviate his fear of being stricken with the plague. Cobbet arrived in America on June 26, 1637, and became a colleague of Reverend Samuel Whiting of Lynn, Massachusetts; even though Lynn had been settled just eight years before, the population had already grown enough to warrant the services of two ministers. He was known for being a very serious man who was both revered and feared by many who attended his services. On one occasion, it was recorded that a few of his neighbors, all women, were practicing some sort of witchery. Before they had finished, Reverend Cobbet was spotted walking toward them. The women stopped immediately, and one verbalized her disdain for Cobbet by yelling that “crooked-back Cobbet” was coming.

After only one year of service, Cobbet was granted two hundred acres of land in Lynn. In 1654, he was appointed as an overseer of Harvard College by the General Court of Massachusetts. He served as a minister in Lynn until 1656, when he became pastor of a church in Ipswich, Massachusetts. Cobbet was also an author and published several books on the subject of religion during his lifetime, one of which was well received by Cotton Mather. He became a prominent member of his community and was eventually able to secure the first grant for land in the area that became Windham. The land, surrounding the pond that would one day bear his name, was surveyed in October 1662 and approved by the General Court of Boston on May 27, 1663. The land composing Windham was under the control of Massachusetts until a separate government was established to form New Hampshire in 1680.

It is unknown if Cobbet ever visited his land in Windham, as there were no apparent improvements made on it, nor were there any European settlers on it before 1719. Cobbet did remain at his post in Ipswich until his death on November 5, 1685. His mourners consumed a barrel of wine and two barrels of cider at his funeral; spice and ginger were added to the cider as the day was quite cold. He was survived by his wife, Elizabeth, and four children: Samuel, John, Thomas and Elizabeth. His wife passed away one year later.