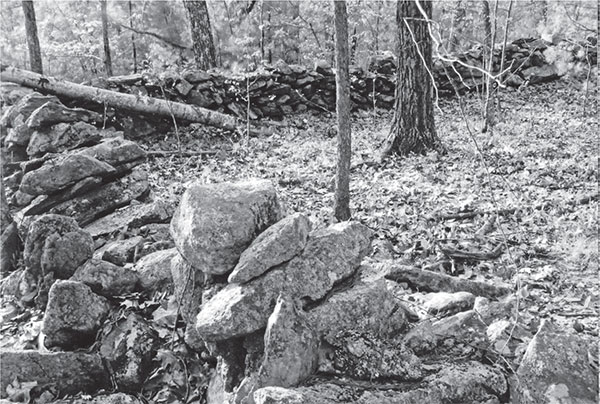

The wall of the sheep pen on the former pastureland of David Gregg. Windham Historic District/Heritage Commission.

4

THE GREAT MERINO SHEEP CRAZE

Before the discovery of gold in California and Alaska, Americans were caught up in a craze unlike any the nation has ever seen before or since. Up until the early nineteenth century, the export of Merino sheep from their native land of Spain was banned. The breed of sheep was desired throughout Europe and North America for its high-quality wool, which was known for its water-repellant qualities. At that time, almost every flock of Merino sheep was owned by either the Catholic Church or the Spanish royal family, with a few rare exceptions of flocks of the sheep being given as gifts to Spanish nobility. Merino sheep were so prized by Spain’s ruling family that the penalty for taking even one sheep beyond the borders of the nation was death.

Much like the Chinese porcelain and silk of centuries ago, the government saw the sheep as an asset to their nation, which they were able to control. For centuries, Spain controlled the Merino sheep market with an iron fist. However, William Jarvis, the U.S. consul to Lisbon, Portugal, arrived in the nation at an opportune time, just as Napoleon Bonaparte was beginning to break Spain’s monopoly on the sheep. Jarvis was successful in purchasing a flock of Merino sheep from the royal family. The exportation of the four thousand sheep he purchased would signal the crumbling of Spain’s sheep empire. Thus, Jarvis was forced to smuggle the sheep out of Spain and onto the ship awaiting to bring him, and the flock, back to the United States. Since he was still on official duty from the U.S. government, Jarvis ensured his superiors were notified throughout the smuggling operation.

The sheep were brought back to Jarvis’s farm in Weathersfield, Vermont. Eight sheep were gifted to Thomas Jefferson, as it was Jefferson who appointed Jarvis to his post, and several sheep were also given to then president James Madison. However, Jarvis did not want to keep the valuable sheep in the hands of the aristocratic class as they had been in Europe. Instead, he set out on a nationwide tour to publicize the Merino sheep. As farmers and entrepreneurs began to see the foundations of profitable businesses in the sheep market, Jarvis began to breed and sell flocks of the once rare sheep to anyone who was interested. He eventually branched out into selling Merino wool throughout Europe and America.

Jarvis owed a great deal of his success in the sheep business to fortunate timing with world politics, not only when he obtained the sheep but also when he began to sell the sheep. When blockades during the War of 1812 prevented British wool from reaching America, the demand for domestically produced wool soared. Americans were now able to purchase some of the finest-quality wool in the world. Farmers all over the eastern states, especially those of New England, clamored at Jarvis’s door wanting to buy as many Merino sheep as they could raise.

There were undoubtedly at least a few farmers in Windham who could not resist the allure of the exotic sheep. One of these was David Gregg, whose pasture on a hill just happened to be the perfect grazing grounds for his newly acquired Merino sheep. So enamored of this new business, Gregg constructed a stone wall by hand to enclose about thirty-four acres of pastureland for his sheep. One can imagine the time spent as Gregg, and very likely some hired hands, toiled away day after day to build stone walls a couple feet high in a near perfect square that measured about 1,200 feet on each side. Gregg was not alone in constructing stone walls, as almost a quarter million miles of them were constructed across New England to serve as enclosed meadows for sheep.

While Gregg went about his new operation with determination and a strong work ethic, not everyone anxious to get into the sheep business was so honest. Although his surname has been lost to history, there is a record of a man by the name of Joseph, who, not wanting to construct time- and labor-intensive stone walls, decided to build a small pen out of large pine branches in the woods near his home. Next, he absconded with several sheep from his neighbor’s pens, having in mind an unusual scheme to keep his stolen property undetected. As sheep were an important part of a farmer’s livelihood, each animal was marked on the ear in a distinctive way to indicate the owner. To remedy this problem, Joseph cut off the ears of the sheep he stole close enough to their heads so that it would be impossible to determine their rightful owner. Whether Joseph succeeded in his scheme might never be known, but it is certainly a telling story of what desperate measures a man will go to when he becomes obsessed with a financially lucrative craze.

The wall of the sheep pen on the former pastureland of David Gregg. Windham Historic District/Heritage Commission.

One of the corners of the Gregg sheep pen. Windham Historic District/Heritage Commission.

stole close enough to their heads so that it would be impossible to determine their rightful owner. Whether Joseph succeeded in his scheme might never be known, but it is certainly a telling story of what desperate measures a man will go to when he becomes obsessed with a financially lucrative craze.

As there were no woolen mills located in Windham at the time, the Merino wool produced in town was likely either sold to local woolen mills or merchants. Not only did the Merino wool reach the price of fifty-seven cents per pound during the craze, but the specific breed of sheep was also more productive than the other two breeds that were previously popular. Merino sheep were able to produce wool to a ratio of about 15 percent of its total body weight. The other breeds of sheep usually yielded wool equivalent to about 6 percent of body weight.

However, Windham farmers, such as David Gregg, were eventually forced out of the Merino sheep business due to changing economic conditions, including the introduction of tariffs. During the 1820s and 1830s, the U.S. government was continually changing tariff laws, sometimes favoring the domestic producers of wool and other times favoring imported wool. As Europe was also a large player in the Merino wool market, they proved to be cutthroat competition for the small-time farmers and larger merchants of the Northeast. Jarvis worked hard to save the market he had created, spending tens of thousands of dollars trying to convince legislators, and the public, to support measures to protect American wool producers.

However, Jarvis was unsuccessful, and the wool market continued to deteriorate. As a result, the pasture on the high hills of the Gregg family’s farm fell out of use, and the land was sold to Asa Buttrick of Pelham, New Hampshire, just as the Merino sheep craze was winding down. While prior to the Industrial Revolution the typical Windham family might have kept a small flock of sheep for personal use, this tradition faded out along with the Merino sheep craze. With the advent of mills in Lowell and Lawrence, Massachusetts, woolen goods could be more easily mass produced. Purchasing manufactured woolen goods, or even wool itself, became easier and more affordable than raising sheep.

By 1840, the price of Merino wool had dropped to only twenty-five cents per pound. Although the farmers of Windham and southern New Hampshire were affected by the downturn of the wool market, the farmers of Vermont were hit especially hard. The relatively low cost of wide expanses of land in the new western territories made it much more affordable to compete with the farmers in the East. While those willing to make the arduous journey to the West were rewarded with competitive advantages in the wool market, some East Coast farmers were forced to slaughter their flocks rather than spending the money to feed them.

The downturn in the sheep market also came at a time when the new factory jobs being created in Lowell and Lawrence began to look more attractive to the younger generation of Windham than a life of farming. Most of the young men lured away from Windham by mill jobs were interested in the money they could make; many of them had helped to construct the dam and canals of Lowell and realized how lucrative that line of work could be. Almost all young boys over the age of fourteen left Windham for one of the mill cities, with some as young as twelve preferring millwork to work on the family farm. Not only was the pay better, but there were also many other benefits to working in the mills.

The millworkers were provided housing in recently built boardinghouses that were much more attractive to young boys than a room at the family homestead. Also, there were many young women working at the mills, and this arrangement proved to be quite enticing to teenage boys. There were certainly many more young ladies at the mills than in a small, rural town. In fact, many of the young men remained in Lowell for the rest of their lives, leaving Windham nearly void of an entire generation. This also contributed to a large decline in the population of Windham, a problem compounded even further when the older residents of Windham left town in order to join their children in Lowell or elsewhere in the country.

The trend of younger generations leaving Windham with the advent of new technology, such as that which led to the development of the railroad or that which spawned the Industrial Revolution, became unfortunately all too common in rural New Hampshire towns, where idyllic ponds and woods proved to be no match for the promise of new, exciting industries. Even more unfortunate for the agriculture industry in general, wool production was one of the largest sectors of New England’s economy, and many farmers struggled to feed their families, with the luckier farmers simply moving into another line of business. As with the Dutch tulip craze, gold rushes and many other crazes and fads of the past, the story of the Merino sheep craze remains a testament to the disadvantages of risking it all when jumping on the bandwagon of the latest moneymaking scheme.