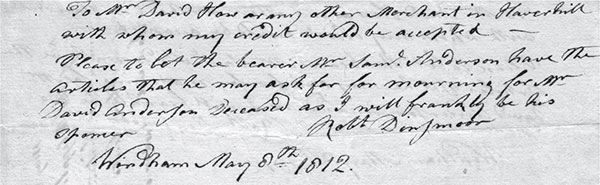

The promissory note signed by Deacon Robert Dinsmoor allowing Samuel Anderson to obtain any articles required for the mourning of his father, David Anderson. Author’s collection.

5

THE “RUSTIC BARD”

Windham range in flowery vest,

Was seen in robes of green, While Cobbet’s pond, from east to west,

Spread her bright waves between.

Cows lowing, cocks crowing, While frogs on Cobbet’s shore,

Lay croaking and mocking The bull’s tremendous roar.

The above is just one short excerpt from the work of Windham’s Deacon Robert Dinsmoor, a renowned Scotch-Irish poet better known as the “Rustic Bard.” Born in Windham on October 7, 1757, to one of the town’s founding families, Dinsmoor had a childhood typical of that of many young boys during the period. As was common in colonial America, especially in a newly settled rural town, Dinsmoor was not afforded the luxury of an education until he was nine years old. His earliest experience with education came from an old British soldier who came to the Nutfield area following his service in the French and Indian War. The elderly soldier taught young Dinsmoor biblical scriptures, which he would memorize regardless of length. Even at a young age, he was able to appreciate the benefits of the education he was receiving and is recorded as having written to a friend that he hoped he would never stray from this religious background.

Dinsmoor’s first experience with a formal education came several years later when he became a pupil of a man known as Master McKeen. Not only did McKeen instruct his pupils in the academic subjects of the day, but he also often took them squirrel hunting. If anyone can be credited with launching Dinsmoor’s poetical career, it might be McKeen, as it was under the direction of this teacher that the young man was first exposed to academic writing, as well as English. Although Dinsmoor excelled in both the former and latter subjects, he lamented later on in life that he had not performed well in arithmetic because he was too busy with his involvement in an early love interest.

With the advent of the Revolutionary War, Dinsmoor joined the army at the age of eighteen. Although he served only three months, one of the highlights of his military career was serving at the Battle of Saratoga. Dinsmoor later served in the army again for several short periods of time. With military life behind him by the time he was twenty-five, Dinsmoor married Mary Park of Windham and settled down to spend the rest of his life farming the open fields on the east side of Cobbett’s Pond, land that had belonged to his father. Serving as an elder in the Windham Presbyterian church for about fifty years, Dinsmoor certainly remained true to his faith and discharged his duties as a deacon with the utmost sincerity and devotion.

Dinsmoor had been a talented poet since relatively early in his life. It is during this period of his life that he adopted the nom de plume “Rustic Bard,” which he signed to his earliest newspaper contributions. His work was usually marked by a distinctive Scotch-Irish dialect that had ties to his ancestral roots. This nod toward his ancestry reflected his love for the Scotch-Irish customs, language and culture. Several of his poems do make a direct reference to his heritage. However, many of his other works were written for various reasons.

One, according to John Greenleaf Whittier, was written to relate a priest’s frustration as a dog “rattled and scraped” at the door while a sermon was being given. Whittier also noted that Dinsmoor wrote poems to “amuse his neighbors” and sometimes to ease tensions after a “domestic calamity.” The bard also wrote about farm life and ordinary events, usually writing using the common man’s dialect, describing things plainly and simply. A notable example of a poem based on his own life was written shortly after the death of his wife. An excerpt from the work is as follows:

The promissory note signed by Deacon Robert Dinsmoor allowing Samuel Anderson to obtain any articles required for the mourning of his father, David Anderson. Author’s collection.

No more may I the Spring Brook trace,

No more with sorrow view the place Where Mary’s wash-tub stood; No more may wander there alone,

And lean upon the mossy stone

Where once she piled her wood.

’Twas there she bleached her linen cloth,

By yonder bass-wood tree;

From that sweet stream she made her broth,

Her pudding and her tea.

That stream, whose waters running,

O’er mossy root and stone,

Made ringing and singing,

Her voice could match alone

Reflecting on his late wife doing the family’s laundry and retrieving water from a nearby stream for cooking, Dinsmoor wrote about the daily chores that represented some of his most cherished memories of his late wife, who passed away at the age of thirty-eight in 1799.

On December 31, 1801, Dinsmoor married Mary Anderson, the widow of Samuel Anderson of Londonderry. Marrying a father of twelve, Mary was forced to quickly adjust to the arduous task of being a stepmother to such a large family. Shortly after moving to the Dinsmoor homestead, she became a motherly figure not only to her own children, and eventually grandchildren, but also to the young children of the community, who affectionately gave her the nickname “Aunt Molly.”

It was after his marriage to Mary Anderson that Dinsmoor began to take his poetry more seriously, publishing many works in local periodicals. In 1828, a collection of the Bard’s poems were published in a small volume printed in Haverhill, Massachusetts. It was this publication that can be given much of the credit for cementing Dinsmoor in his place as one of history’s preeminent Scotch-Irish poets. Unbeknownst to the original audience of Dinsmoor’s Incidental Poems , a relatively unknown poet by the name of John Greenleaf Whittier who contributed a single poem to the book would become one of the greatest poets in the history of the nation. Whittier and Dinsmoor became friends, but the two seldom interacted with each other.

In about 1816, Dinsmoor was the victim of a “paralytic shock” that nearly claimed his life. He also suffered from severe rheumatism later in his life, which at times made it impossible for him to stand completely erect.

Nearing the end of his life, Dinsmoor is described by Whittier as:

chaffering in the market-place of my native village, swapping potatoes and onions and pumpkins, for tea, coffee, molasses, and, if the truth be told, New England rum…He still stood stoutly and sturdily in his thick shoes of cowhide, like one accustomed to tread independently the soil of his own acres,—his broad, honest face seamed by care and darkened by exposure to “all the airts that blow,” and his white hair flowing patriarchal glory beneath his felt hat. A genial, jovial, large-hearted old man, simple as a child.

The Rustic Bard died of pneumonia at the age of seventy-nine on March 16, 1836. His widow lived on to survive him by nearly two years, dying on January 19, 1838.