The first organized movement dedicated to the technologization of art and humanity was called Futurism, and it was articulated in a 1909 manifesto by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti.* The Futurists were a group mostly of Italian artists who were disgusted with representational art’s limits and its clichés—right angles, landscapes, the nude. Marinetti and the Futurists were determined to “destroy the cult of the past, the obsession with the ancients, pedantry and academic formalism. Totally invalidate all kinds of imitation. Elevate all attempts at originality, however daring, however violent.”1 Beyond severing all ties with the morality and forms of the past, Futurism’s determination to explore the new was intolerant even of the present (hence the movement’s name). Instead, it focused on the impact of the present against the future: the eternal, instantaneous cutting edge. Futurists were artistically obsessed with swift, explosive action as an aesthetic: sounds, images, and forms that perpetually propelled into newness. Struggle and penetration were central themes in Futurist art, which sometimes took on a violent guise; the movement’s admiration of war and brutality, tied in with its peculiar Italian nationalism, led many of its adherents ultimately to Fascism. Futurists even reveled in the antagonism between themselves and their audiences: “We will … bear bravely and proudly the smear of ‘madness’ with which they try to gag all innovators.”2

This longing for confrontation, novelty, and speed found a potent metaphor in technology. Marinetti called Futurism “the aesthetics of the machine,” and indeed, the signification of the machine as an idea resonated with Futurist thinking on at least two important levels. First, machines were themselves capable, in theory anyway, of the ceaseless motion that so fascinated Marinetti and his followers—the “eternal, omnipresent speed.”3 Machines could unsentimentally enact a combustion that bespoke vitality itself. Second, in the early twentieth century, the machine was an ever-evolving, ever-improving symbol of modernity. Progress—without regard to Old World aesthetics or morality—drove mankind’s development of the machine, and as workers organized into systematic assembly lines to weld metal on metal, they mimicked the very technology they built. And so it was that mechanization was central to Futurism. By embracing the art made possible by machines, these brash Italian artists were themselves at the vanguard of new human sensory experience.

Perhaps the most famous document of twentieth-century technophilia is Luigi Russolo’s 1913 Futurist manifesto The Art of Noises. Enamored with the musical possibilities inherent in recorded sound, Russolo envisions a symphony of clanging metal, creaking wood, scraped dishes, howling animals, and running water. He bellows that

by selecting, coordinating and dominating all noises we will enrich men with a new and unexpected sensual pleasure. Although it is characteristic of noise to recall us brutally to real life, the art of noise must not limit itself to imitative reproduction. It will achieve its most emotive power in the acoustic enjoyment, in its own right, that the artist’s inspiration will extract from combined noises.4

Russolo’s conceptual attempt to separate pure sounds from the connotations of their sources was what differentiated his “Futurist orchestra” from earlier incorporations of noise into music, which had been mere novel amusements.

Russolo not only laid the theoretical foundation for sampling as both an associative practice and a purely sonic listening experience—what the French pioneer of musique concrète Pierre Schaeffer called “reduced hearing”—but he enacted it too. For the year or two that followed “The Art of Noises,” Russolo and fellow Futurist Ugo Piatti constructed hand-cranked musical instruments called Intonarumori, building up a large ensemble with which they hissed, cracked, and clattered for dubiously receptive audiences. In the grand tradition of Igor Stravinsky’s brutal The Rite of Spring, Russolo and Marinetti incited a riot at their debut performance in Rome, April 1914. Crowds in London begged the musicians to stop playing, leading Marinetti, ever confrontational and sensationalistic, to consider the exhibitions a tremendous success.5

The image of high-concept artists terrorizing British audiences with noise music is eerily prescient of the legendary early performances of Throbbing Gristle, who in the mid-1970s took the same scandalous glee in confounding popular aesthetics and morality. This contrarian streak isn’t merely incidental in Futurism and industrial music alike. Just as Marinetti asserts, “Except in struggle, there is no more beauty. No work without an aggressive character can be a masterpiece. Poetry must be conceived as a violent attack,”6 industrial music too has inherent themes of physical exertion, struggle, and war.

The connection across sixty-five years of artistic movements from Futurism to the dawn of industrial music is far from academic speculation; Futurism is explicitly cited in the music of bands like Spahn Ranch, Nurse With Wound, and Pornotanz, among others. First-wave industrialist Monte Cazazza took part in a 1975 performance in San Francisco, A Futurist Sintesi, that attempted to revive the movement’s spirit, and German industrial legends Einstürzende Neubauten not only pay lyrical tribute to Marinetti in their 2007 song “Let’s Do It Dada,” but their 1993 video for “Blume” uses a physical replica of Russolo’s Intonarumori as both set and props. Brian Williams, the man behind ambient industrial act Lustmord and a musician with collaborations in the scene ranging from SPK to Chris & Cosey to Clock DVA to Monte Cazazza, wrote in 1996, “Over the last two decades terms such as ‘industrial’ … have been applied to an ever increasing and ever more bewildering array of musicians. … It is appropriate to attribute the actual origin of modern sonic experimentation to the writing of the Futurist manifesto ‘The Art of Noises’ by Luigi Russolo.”7

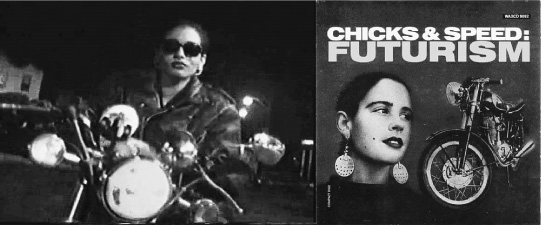

More than just a point of explicit reference, Futurism pervades industrial music symbolically. Consider the music video for Revolting Cocks’ 1988 “Stainless Steel Providers.” The clip begins with a montage of industrial tools machining parts for a motorcycle, and then a leather-clad young woman drives the motorcycle in dizzyingly sped up motion through night traffic. The band members then douse the motorcycle in gasoline, set it ablaze with a blowtorch, and throw it off a building.

Marinetti begins his original manifesto with a rhapsodic worship of “the famished roar of automobiles”: “And on we raced, hurling watchdogs against doorsteps, curling them under our burning tires like collars under a flatiron. Death, domesticated, met me at every turn, gracefully holding out a paw, or once in a while hunkering down, making velvety caressing eyes at me from every puddle.”8 Shortly after in his narrative, Marinetti crashes his car while swerving to avoid two bicyclists—symbols of outdated ignorance. We might read this as an illustration that sympathy for the outmoded destroys progress, but Marinetti, in crashing, also experiences a new Futurist joy: the revelation of the collision, the violent thrill that comes when speed, technology, and motion outgrow the surrounding world. Thus the high-velocity crash—the explosion—is a means of expanding the constraints against which art, in the eyes of the Futurists, must struggle, regardless of how self-destructive its effects. This was a powerful idea that resurfaced in the work of the Vienna Aktionists in the 1960s and most famously in J. G. Ballard’s 1973 novel Crash, where car wrecks literally become the subject of sexual fetish.

This helps us better understand the progress throughout the “Stainless Steel Providers” video, where Futurism’s tropes are presented in progressively radical forms: the band builds the technology, tests and enjoys its speed, and then destroys it redundantly, with the gasoline dousing shot repeated, suggesting a perpetual violence through fire and its crash off the rooftop. All of this is set to the backdrop of singer Chris Connelly’s feverish chanting:

It bleeds efficiency

The way I feel on stainless steel,

And all it does to me

Stainless steel providers

Another tire

Let it catch on fire

A metal motor mantra

Makes you waste the time of day

You’ll sit on a timebomb, forever and ever

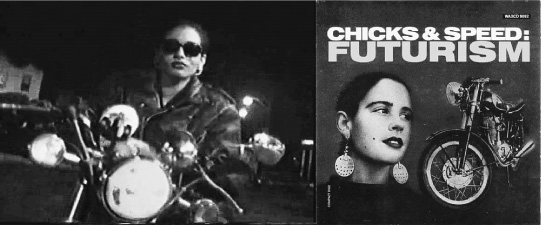

The Futurist compatibilities of the song become more striking when we see the reappearance of the fishnet-clad woman and her motorcycle a year and a half later, emblazoning the cover of an EP by Lead Into Gold, a band whose every last member (Al Jourgensen, Paul Barker, and William Rieflin) also played in Revolting Cocks. The name of this EP is Chicks & Speed: Futurism, and its lead single was called “Faster Than Light.”

Figure 1.1: A video still from “Stainless Steel Providers” by Revolting Cocks and the album cover of Chicks & Speed: Futurism by Lead Into Gold starkly echo Futurist themes. Video directed by Eric Zimmerman and photographed by Eric S. Koziol; album cover photograph by Brian Shanley; model/driver: Judy Pokonosky.

Drawing so many explicit connections between industrial music and Futurism may belabor the point of their connectedness, but it serves another significant purpose: it demonstrates that the individuals making this music were not merely tapping into a mind-set that was incidentally similar to an important artistic movement in the past, but were themselves literarily aware of Futurism, of artistic philosophy, of critical theory. One reason, then, why it’s important to consider industrial music so high-mindedly is that the genre itself is at least on occasion consciously engaged in literary discourse. This can happen even at its trashiest moments, of which more than a few belong to Revolting Cocks.