Princess Margaret felt most at home in the company of the camp, the cultured and the waspish. It was to be her misfortune that such a high proportion of them kept diaries, and moreover, diaries written with a view to publication. To a man, they were mesmerised less by her image than by the cracks to be found in it. They were drawn to her like iron filings to a magnet, or, perhaps more accurately, cats to a canary.

Some were blessed with peculiar prescience. As early as June 1949, when Margaret was only eighteen, Chips Channon spotted her at a ball at Windsor Castle. ‘Already she is a public character. I wonder what will happen to her? There is already a Marie Antoinette aroma about her.’*

Seven years later, on 21 July 1956, the historian A.L. Rowse noticed the twenty-five-year-old Princess at a Buckingham Palace garden party. ‘Interesting to watch her face, bored, mécontente, ready to burst out against it all: a Duke of Windsor among the women of the Royal Family.’ She was also attracting opprobrium from other, less well-connected diarists, among them Anthony Heap, the local government officer who was writing his diary for Mass-Observation. ‘When is Princess Margaret going to be her age (which is 26) and behave like a member of the Royal Family instead of a half-baked jazz mad Teddy Girl?’ he asked. ‘For what should be reported in this morning’s papers but that last night she went to see the latest trashy “rock ’n’ roll” film [The Girl Can’t Help It] at the Carlton – she never goes to an intelligent play or film – and, taking off her shoes, put her feet up on the rail round the front of the circle and waved them in time with the “hot rhythm”.’

A few days after Channon’s sighting of her at Windsor, the Princess merited her first mention in the diaries of the camp, waspish, etc. James Lees-Milne, after his friend, the camp, waspish, etc. James Pope-Hennessy, told him that the Princess was ‘high-spirited to the verge of indiscretion. She mimics Lord Mayors welcoming her on platforms and crooners on the wireless, in fact anyone you care to mention.’

By the 1960s there were at least two more diarists biting at her heels: first Cecil Beaton, and then, towards the end of the decade, the up-and-coming young museum director Roy Strong. Beaton tended to zero in on her face and her clothes, on red alert for mishaps in both departments. On 4 May 1968, he went with his friend Dicky Buckle to watch the Danish Ballet at Covent Garden. He found the performance ‘agony’, but there was amusement provided by having ‘a good gawk’ at the Royal Box: ‘Princess Margaret with an outrageous, enormous Roman matron head-do, much too important for such a squat little figure’,* and ‘the common little Lord Snowdon, who was wearing his hair in a dyed quiff’.

Ten days later, on 14 May, Princess Margaret spent the evening with yet another closet diarist, Lady Cynthia Gladwyn. We have already seen how Lady Gladwyn recorded with icy precision the Princess’s wayward misbehaviour in Paris in the spring of 1959. Nine years on, at a party at St James’s Palace, she noticed that Lord Snowdon’s hair was ‘tinted in a curious new colour. Sachy Sitwell afterwards described it as peach, but I would say apricot.’ Six months later, she was invited to see a pair of Italian plays, Naples by Day and Naples by Night. Though she found them ‘a little slow in places’, her interest was again quickened by the recently refurbished hair of Lord Snowdon, who was sitting immediately in front of her. Against his fashionable white polo-necked jersey, it now seemed ‘auburn coloured … dressed in two handsome waves, the perfection of which seemed to preoccupy him very much’.

After the theatre, the group went on to the Italian embassy for dinner. Sadly, they found themselves trapped there, unable to leave before Princess Margaret, who clearly had another late night in mind. ‘She kept on approaching the door, and just as we were encouraged to think she was really about to take her departure, she suddenly went back into the centre of the room and became engaged in animated conversation – all just to tease and annoy.’

Inevitably, the Princess’s performance set tongues a-wagging. Diana Cooper told Lady Gladwyn of the time she had stayed at Hatfield. After dinner, there had been calls for the Princess to play the piano or to sing, but she had refused right up until everyone wanted to go to bed, at which point she had beetled over to the piano and played it until four in the morning. Needless to say, even the sleepiest guests had bowed to royal protocol, listening until the bitter end.

Roy Strong first encountered Princess Margaret on 27 November 1969, at a dinner thrown by the soon-to-be Lady Harlech to celebrate the opening of his exhibition ‘The Elizabethan Image’ at the Tate Gallery. In his diary, the thirty-four-year-old Strong noted that the Princess, ‘wearing a cream sheath dress with a bolero in pink’, refused to sit down for three quarters of an hour, ‘thus obliging the pregnant Ingrid Channon to remain standing for all that time’.

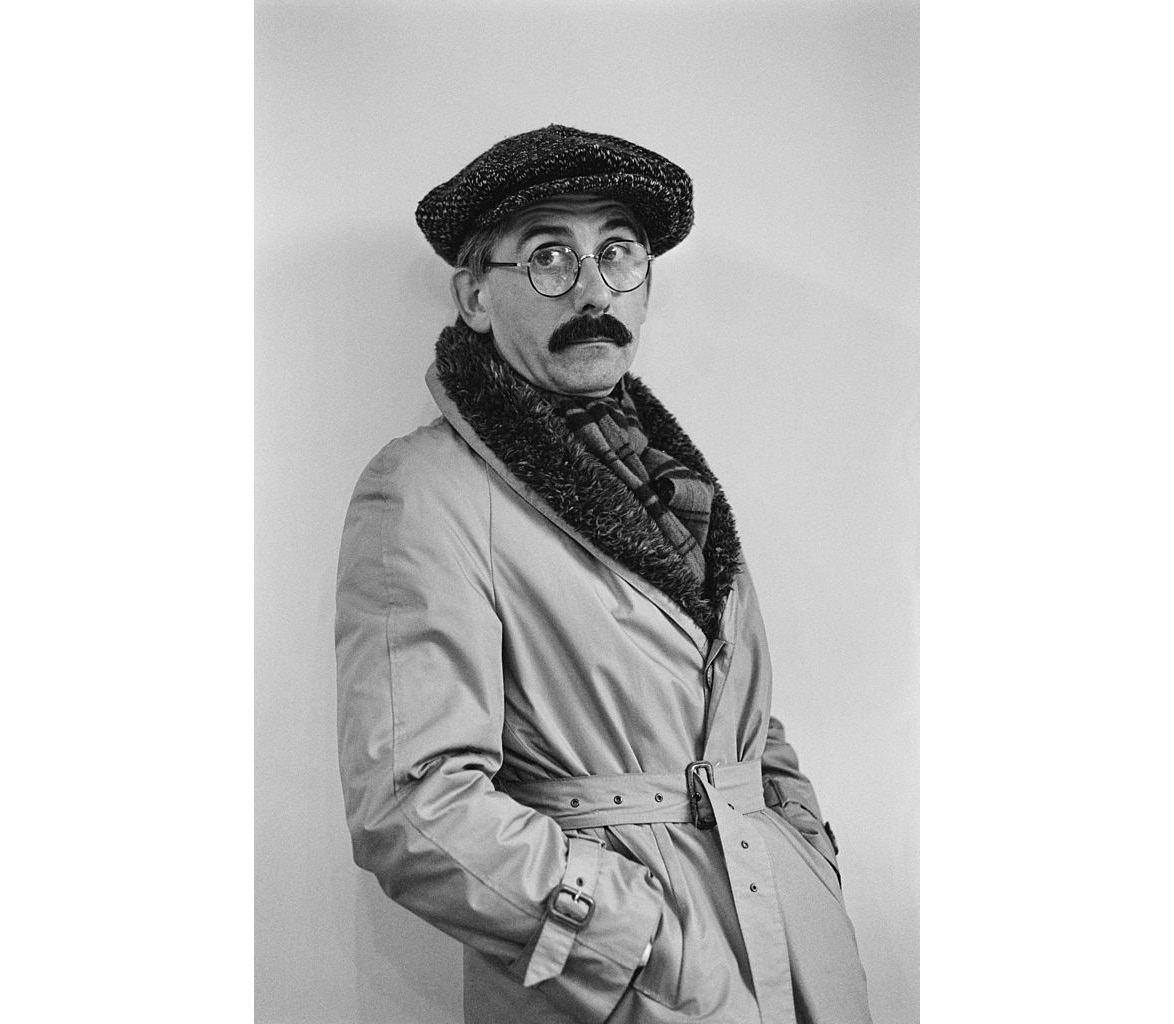

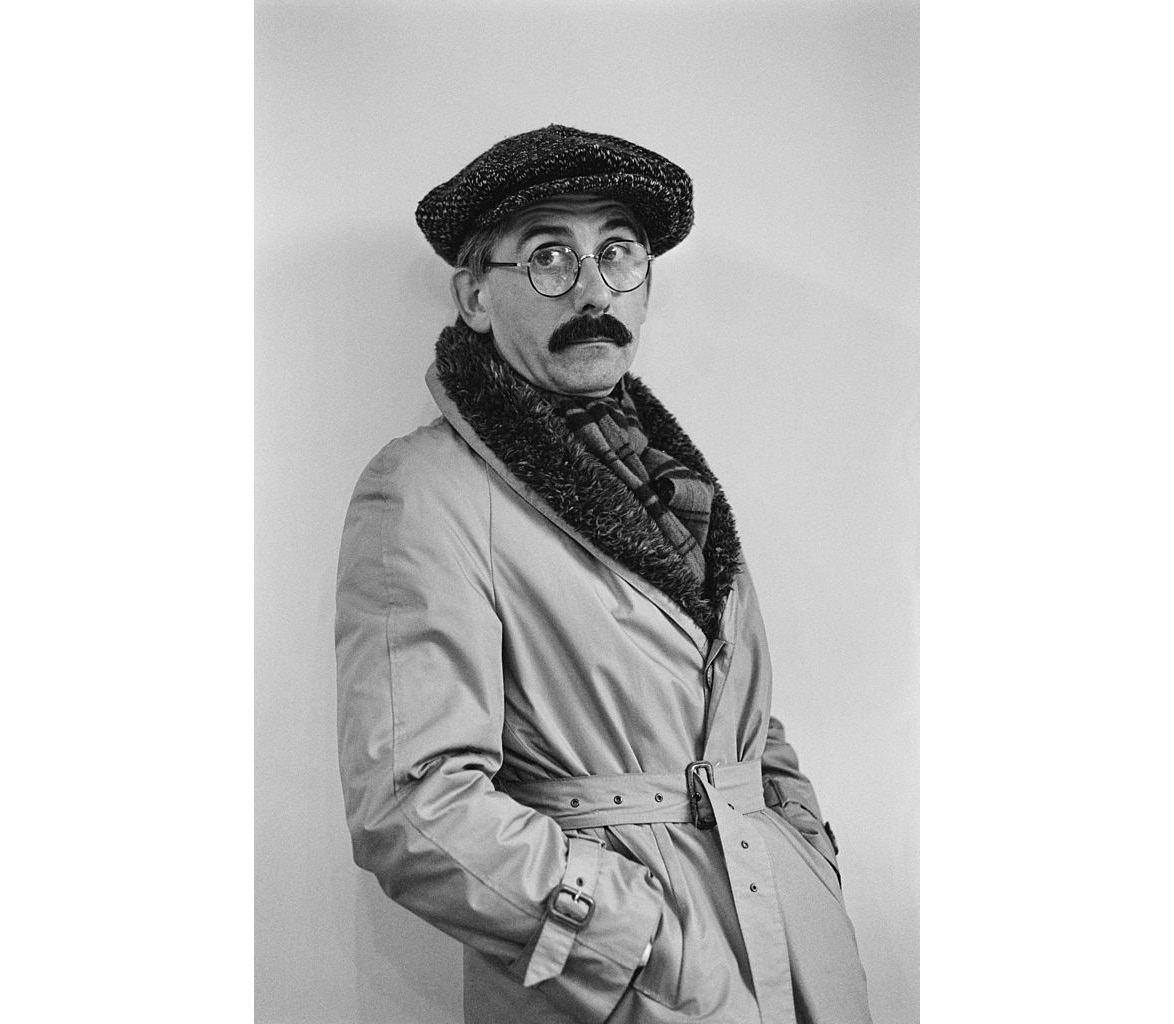

(John Downing/Getty Images)

Placed next to Strong, the Princess made her dissatisfaction obvious, ignoring him until the pudding course. ‘Then she wiped her plate slowly with her napkin, at which point Beatrix* leaned over and said, “The food here’s great but let’s face it the washing-up’s rotten.”’ After escorting the Princess around the exhibition, Strong concluded that ‘Princess Margaret is a strange lady, pretty, tough, disillusioned and spoilt. To cope with her I decided one had to slap back which I did and survived.’

Earlier that year, Cecil Beaton had been unimpressed by the television documentary The Royal Family, finding Princess Margaret ‘mature and vulgar’, and her husband, his professional rival Lord Snowdon, ‘common beyond belief’.* He encountered the royal couple in the flesh at a party held at Windsor Castle in April 1972 for bigwigs in the arts, including Flora Robson, ‘in a terrible wig’, and Lord and Lady Olivier, who were ‘cheap and second rate’. Beaton was, however, rather more forgiving towards Princess Margaret, who at least ‘managed to create a solid, clean, well-sculpted simplicity of line and colour’, though this pleasing effect was offset by the way in which ‘she wore harsh white and hair scraped back like a wealthy seaside landlady’. But at least she fared better beneath his unforgiving gaze than Queen Juliana of the Netherlands, who, said Beaton, ‘looked nice and cosy and sympathetic in spite of her ugly little face with unseeing small eyes and pig snout …’*

On Wednesday, 28 June 1972, James Lees-Milne and his wife Alvilde ‘motored’ to London for a private screening of John Betjeman’s television documentary about Australia. They didn’t know who else was going to be there, but Lord Snowdon arrived, ‘full of vitality and cheer’, and started talking to them about Bath, where they lived. Next came Princess Margaret, followed by the Prince of Wales. ‘I was taken aback,’ wrote Lees-Milne in his diary, ‘not having expected such.’

After the screening, they all went for dinner in a private room at Rules restaurant. The party consisted of Patrick Garland (director of the documentary), James Lees-Milne, John Drummond (producer of the documentary), Princess Margaret, John Betjeman, Alvilde Lees-Milne, Lord Snowdon, Elizabeth Cavendish (Betjeman’s girlfriend), the Prince of Wales, Jenny Agutter (actress girlfriend of Patrick Garland), and Mary, Duchess of Devonshire.

By his own account, Lees-Milne ‘hardly spoke a word to the royals but watched them closely’. He found Prince Charles ‘very charming and polite’, but considered Princess Margaret ‘far from charming … cross, exacting, too sophisticated, and sharp’. On the other hand, she was ‘physically attractive in a bun-like way, with trussed up bosom, and hair like two cottage loaves, one balancing on the other’. In a letter to Betjeman he elaborated on this description, saying he found her ‘very very very frightening but beautiful and succulent like Belgian buns’. He noticed that the Princess never spoke to Betjeman, but ‘smoked continuously from a long holder’.

Prince Charles had to leave the dinner early in order to drive to Portsmouth. Elizabeth Cavendish had removed her shoes, so to see the Prince off she went downstairs and into the street without them, saying ‘Mind you drive carefully’ to the driver.

While she was out in the street, Princess Margaret leaned down to pick up the abandoned shoes, and placed them on her plate. This irritated Lord Snowdon. ‘It’s unlucky, I don’t like it!’ he snapped. In response, Princess Margaret removed the shoes from the plate, put them on her chair, and walked to the window in a sulk. Twice she said she wanted to leave; twice Snowdon insisted on waiting another five minutes. Eventually, Patrick Garland agreed to drive the Princess home in his Mini.

Snowdon then extracted promises from the rest of them to come back to Kensington Palace. Once he had left, they debated whether or not to join him, as he had asked. ‘I did not want to go because I thought Princess M. would not be pleased,’ reflected Lees-Milne. But in the end they decided to go; they were giving the Duchess of Devonshire a lift home, and were sure she would not want to linger.

On entering Kensington Palace, Lees-Milne found Princess Margaret ‘more gracious to me … but I did not find conversation very easy or agreeable’. As fate would have it, another writer was also there that night, jotting it all down, this time for an auto-biography. From John Drummond we learn that they all remained at the palace until two in the morning, ‘since the Princess never seemed to tire’.

Once home, Lees-Milne mentioned to his wife that after sitting down in a chair which Prince Charles had just vacated, he had drunk some water out of the Prince’s glass, ‘which I enjoyed doing’, adding that ‘I would not have drunk out of PM’s.’ Alvilde agreed with this judgement, and told him that she had gone into the loo with Princess Margaret and sat on the same seat after her, ‘but would rather have sat on the one Prince Charles had just sat on’. Such are the more recondite pleasures of proximity to royalty.

The diarists hovered around her like hornets. In November 1972 Cecil Beaton took a good long look at her during the service of thanksgiving for the silver wedding of the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh at Westminster Abbey, noting in his diary her ‘set smile on a well-enamelled face’, but condemning her ‘fatal choice of putting on a black coal heaver’s hat with a dark red dress’. But at least she did better than ‘that awful John Colville,* his mouth now turning down like a croquet hoop’.

The following year, on Wednesday, 20 June 1973, James Lees-Milne attended (‘honoured to be asked, but reluctant to go’) a concert party at Windsor Castle. The ensuing dinner went on well past midnight. ‘I avoided Tony Snowdon and Princess Margaret. In passing close to her I overheard her saying to Angus Ogilvy, who happened to brush her arm in passing, “Must you do that?” in her snappish voice.’

The presence of royalty in a room acts as a magnet: some are attracted, others repelled. The diarists generally tended to experience both sensations at once, but on this particular evening Lees-Milne placed himself firmly in the camp of the repelled. ‘I didn’t want to get into conversation … how obsequious most people look on talking to royalty, bowing and scraping ingratiatingly. How impossible to be natural. I am sure one must try to be. Yet when it came to saying goodbye to the Queen at the head of the staircase, all I could murmur was, “It has been the greatest treat, Ma’am.” Really, how could I?’

Cecil Beaton came away similarly despondent from a ball at Buckingham Palace to celebrate the wedding of Princess Anne in November 1973. He had gone with ‘high expectations’ to the preceding dinner at Clarence House, but ‘unfortunately I was disappointed … It is a hideous house & the mixture of furniture makes for a rather sordid ensemble. Some of the pictures are so bad … that it gives the appearance of a pretentious hotel.’ Finding the women of the party ‘unbelievably drab’, he was also put off by the food: ‘all too creamy’.

At the ball itself, he was surprised to find that Princess Anne had turned into ‘an Aubrey Beardsley beauty. Never more was I astonished.’ After all, when he had photographed her at the age of thirteen, ‘she was a bossy, unattractive, galumphing girl’, and ‘the pictures were revolting’. Others at the ball included Begum Aga Khan, ‘a common model, with too long fingernails’; Debo Devonshire with ‘her ordinary farmwork hairdo’; Prince Charles, ‘getting very red in the face and rather butch with huge butch feet and legs’; the Kent family, looking ‘cretinous, ghoulish, a bit Addams cartoonish’; and the then prime minister, Edward Heath (‘may I not be damned for saying tonight he exuded a certain sex appeal’).

On his way out, Beaton spotted Princess Margaret, now aged forty-three. He did not like what he saw. ‘Gosh the shock! She has become a little pocket monster – Queen Victoria. The flesh is solid and I don’t think dieting can reduce a marble statue. The weighty body was encased in sequin fargets, of turquoise and shrimp, her hair scraped back and a high tiara-crown … placed on top. But the hairdresser had foolishly given her a vast teapot handle of hair jutting out at the back. This triple-compacted chignon was a target for all passers-by to hit first from one side, then another. The poor midgety brute was knocked like a top, sometimes almost into a complete circle.’

This diary entry goes on at almost manic length about the Princess’s appearance, its malice all the more wounding for being coated with pity. ‘As I talked, a waiter passed with a tray of champagne and once more a biff sent the diminutive princess flying. Poor brute, I do feel sorry for her. She was not very nice in the days when she was so pretty and attractive. She snubbed and ignored friends. But my God has she been paid out! Her appearance has gone to pot. Her eyes seem to have lost their vigour, her complexion is now a dirty negligee pink satin. The sort of thing one sees in a disbanded dyer’s shop window.’

Nor does he miss the opportunity to take a poke at his real bête noire. ‘The horrid husband was nowhere to be seen. It is said that the Queen would be willing to let Pss M get rid of him but Tony won’t go.’

Beaton, Strong and Lees-Milne lapped up all the gossip about Margaret and Tony, particularly when it involved marital turmoil.†† In his diary entry for Thursday, 11 July 1974, Lees-Milne noted that the Duchess of Devonshire had passed on a little gem she had originally heard from Snowdon’s old friend Jeremy Fry, who had himself heard it from someone who had heard it directly from the Princess. ‘P.M. told a friend the other day that she so hates her husband now she can hardly bear to be in the same room as him.’

At a dinner in celebration of the ‘Scythian Gold’ exhibition in Paris on Tuesday, 25 November 1975, Roy Strong observed the Princess ‘in beaming mood, slimmer and wearing quite a weight of make-up, her thin hair heavily back-combed’. She looked, he thought, ‘rather marvellous’, though he felt that ‘she addresses rather than speaks to you, but she revels in tough conversation and anecdotes. She is, as we all know, tiresome, spoilt, idle and irritating.’

Her escort for that particular evening, Colin Tennant, told Strong how the Princess had hated her recent trip to Australia. ‘The traffic lights were not even cancelled any more to let her car through, nor was there a police escort, and no crowds cheering. Imagine the effect of their disappearance, said Tennant, on someone who had come to expect all those things. What did she have to fall back on? She had been brought up as the younger sister, not to offer competition, and was “taught only to dance and sing and that was that”.’

‘She has no direction, no overriding interest,’ concluded Strong in his diary entry for that evening. ‘All she likes now is la jeunesse doré and Young Men.’

The following evening Strong bumped into her again, at a ‘crashingly dull’ dinner at which ‘HRH slugged through the whisky and sodas’. But she cheered up when telling him all about her house on Mustique. Strong said he thought she had a cottage in West Sussex, but she told him it belonged to her husband. At this point, she started raving on and on against Snowdon: how he had upset both the nanny and the chauffeur when she was away in Australia, and how he ‘went away for weekends she didn’t know where and she didn’t know his friends or anything’. Before Strong went to bed that night, he concluded that she was ‘bitter and sad. She looked lonely and soured by it all.’

On 11 April 1976, James Lees-Milne was able to enjoy another ‘good stare’ at the Royal Family from his prime position in the middle of the nave in the church at Badminton, where they were all staying for a three-day event. He had a good view of the Prince of Wales, ‘sporting a beastly beard’, and the forty-five-year-old Princess Margaret, looking ‘miserable, trussed up like a broody hen, pigeon-breasted and discontented’. Once again he reflected on his instinctive aversion to direct contact with royalty. ‘I like the Royal Family to exist, but I don’t want to know or be known by them.’

Six months later, on 25 October, Roy Strong had a correspondingly good view of the Queen, in ‘floating apricot chiffon, quite hideous’, as she arrived at the new National Theatre building for its official opening. While Her Majesty watched Goldoni’s Il Campiello in the Olivier Theatre, Strong went with Princess Margaret to see Tom Stoppard’s Jumpers (‘a play of utter boredom’) in the Lyttelton. The entire evening was, he complained, ‘a washout in every sense of the word’ – and this, he added, was the view of Princess Margaret too. She had, he said, ‘been bored by the play but more by the fact that when she sat down the wall in front of her in the circle was so high that she couldn’t see over it’.*

By the age of forty-two, Strong could claim to be on the inside of Princess Margaret’s outer circle, and steadily inching closer to the centre. On Monday, 13 February 1978 he was invited to a dinner at Kensington Palace in honour of the Marchioness of Cholmondeley. The meal was lavish, ‘starting with lobster and on through the usual game birds, the table heavy with silver and glass’. The Princess was less well covered: she was wearing a ‘virtually topless’ dress, ‘apart from two thin shoulder-straps’. She had placed her young friend Roddy Llewellyn opposite her, ‘in the role of host’. Strong considered Roddy ‘a pretty young blond man but, unlike Tony, not bright. She seems to have thrown all discretion to the winds … It is all rather sad and pathetic and deeply embarrassing for the Queen, surely?’

On Tuesday, 4 April 1978, James Lees-Milne dropped in on Lord Snowdon’s stepfather, the Earl of Rosse,* who was to die the following year. Rosse proved as keen to gossip about the royal couple as anybody. ‘Talked of Princess Margaret and Tony, the latter having been to see Michael the evening before. Michael said the tragedy was that both of them only liked second-rate people. Their friends were awful.’

Two days later, the Strongs clocked up an overnight stay in Windsor Castle. Other guests included the prime minister, James Callaghan, the Turkish ambassador, the Australian high commissioner, and Kurt Waldheim, the secretary-general of the United Nations.* Never backward in coming forward, Strong thought Princess Margaret, suntanned in green, was ‘obviously pleased to see us’ amidst ‘a bevy of people she probably regarded as “heavies”’.

The high point came when Strong found himself in a circle consisting of the prime minister, Princess Margaret and her son, the sixteen-year-old Lord Linley (‘as tiny as his parents’). The avuncular Callaghan asked Linley what he wanted to be when he grew up. ‘A carpenter,’ replied the Princess on his behalf, adding, ‘Christ was a carpenter.’

At 8 o’clock the following morning, the Strongs took breakfast in their private sitting room at the Castle, ‘with flunkeys in attendance’. Alas, all was not as it should have been: ‘the three-minute egg arrived hard-boiled as no one had bothered to tap the top’.

* ‘I wonder what he meant by that?’ the Princess asked her authorised biographer, Christopher Warwick, when he mentioned this remark. There was something of the clairvoyant about Chips Channon. In 1991, when Tim Heald was interviewing Prince Philip for a biography, he was surprised by the way any mention of Channon’s name met with a gruff response. ‘So you’ve hit the Channon nerve,’ said the Duke’s old friend, Mike Parker. It emerged that fifty years earlier, in 1941, Channon happened to meet the young Philip in Athens. ‘He is to be our Prince Consort and that is why he is serving in our navy,’ he wrote in his diary. At that time, Princess Elizabeth was only fifteen years old.

* When her biographer Theo Aronson visited her some years later, in 1982, he nursed similar concerns about her appearance, which he expressed in diaries first published in 2000: ‘Her hair is dyed a deep, glossy auburn; her lipstick is very bright. She is small, with a big bust that gives her a top-heavy look. She is badly dressed, in a black dress patterned in yellow and green squares and is wearing white, high-heeled, platform-soled sandals which, because her legs are so thin, give her a Minnie Mouse look.’

* Beatrix Miller (1923–2014), editor of Vogue 1964–85.

* Princess Margaret was always in two minds about Beaton. She used to tell friends that as he was such a nightmare in company she felt obliged to have him to dinner à deux. He, in turn, would always be thrilled by such exclusive access, imagining he must occupy a special place in her heart.

* Beaton’s pen-portraits are particularly spiteful towards women. At different times in his diaries he calls the Queen Mother ‘fatter than ever, but yet wrinkled’; Joan Plowright ‘like a deficient house-parlour-maid’; Katharine Hepburn successively ‘a complete egomaniac’, ‘a goddamned bore’ and ‘a rotten ingrained viper’; and Elizabeth Taylor ‘this monster’. He then goes on to single out for particular displeasure Taylor’s ‘breasts, hanging and huge, like those of a peasant woman suckling her young in Peru. They were seen in their full shape, blotched and mauve, plum … on her fat, coarse hands more of the biggest diamonds and emeralds.’

* Private secretary to HM the Queen when she was still Princess Elizabeth, and before that to Winston Churchill.

* The diarists were no more loyal to each other than they were to the Princess. Both Lees-Milne and Strong turned on Beaton soon after his death on 18 January 1980. Hearing of ‘appalling and brutal’ caricatures Beaton had once drawn of Violet Trefusis and Vita Sackville-West, Lees-Milne wrote in his diary, ‘Cecil was a bitch really.’ On the day Beaton died, Strong wrote a glowing appreciation of him for Vogue (‘I shall always recall him as he had no wish to be, a marvellous old man, gentle and warm …’), but seventeen years later he inserted an addendum into his diary: ‘What one couldn’t say then but can now is that I remember him too as a great hater … Snobbery, untold ambition, together with envy, were sad defects which marred this remarkable man.’

* Twenty-five years later, a heavyweight biography of Stoppard by an American academic called Ira Nadel paints an altogether sunnier picture of the Princess’s reaction to Jumpers: ‘Her presence and delight in the play prompted a long fascination with Stoppard’s work, which grew into a friendship,’ she writes optimistically.

* Michael Parsons, 6th Earl of Rosse (1906–79). Irish peer, second husband of Anne Messel, whose first marriage, to Ronald Armstrong-Jones, had produced Tony Armstrong-Jones.

* And later discovered to have been a member of Hitler’s SA.