The history museum—place of last resort for orphaned legacies, the unwanted things people cannot keep and cannot sell. At least that is the image conjured up by a popular name for the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History: the nation’s attic. No one knows for sure who coined the phrase, but it has haunted history curators for decades. Despite its familiar and affectionate overtones, the nickname implies mustiness and cobwebs, oddities and castoffs, forgotten and obsolete gadgets, useless junk.

And while that description may apply to a few of the millions of objects acquired over the years, the crucial fact is that the vast majority of artifacts in the National Museum of American History are not here by accident. They are here because someone at some time passionately believed they were worth saving. People have offered things to the museum because they deliberately wanted those objects, their stories, and their meanings to be remembered. They wanted to create a legacy, and they wanted that legacy to be preserved and passed on. Most important, people chose the Smithsonian as the repository for their cherished objects because they wanted to share them with the nation. They believed those objects had value not just as personal or even local or regional legacies but as part of a collective American legacy.

Over the years these objects have been cared for by different curators, transferred to different departments, and exhibited in different buildings as the Smithsonian itself expanded and changed. Originally housed in a single building on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., the Smithsonian Institution now encompasses more than a dozen museums, galleries, parks, and research facilities, extending from New York City to Panama.2

In the beginning, however, there was only the U.S. National Museum. Its roots lay in the collections of natural history, ethnological, industrial, and historical objects owned by the U.S. government and exhibited in the Patent Office building in Washington. After the Smithsonian Institution was established in 1846, Congress designated it the official caretaker of these collections. In 1858 the bulk of the collections was moved into the Smithsonian Castle, despite protests by Secretary Joseph Henry, who wanted the Institution to retain its independence and focus on scientific research. To relieve the Smithsonian of having to use funds from its endowment, Congress established an annual appropriation to support the National Museum.

Spencer Baird, assistant secretary of the Smithsonian (he succeeded Henry as secretary in 1878), presided over the National Museum. A naturalist who had devoted most of his life to collecting, Baird had arrived at the Smithsonian in 1850 with an extensive bird collection and a strong desire to develop a museum of natural history in Washington. As head of the National Museum, he set about creating a network of scientists, explorers, and traders who would supply the museum with specimens of flora and fauna collected from all corners of the earth and especially from North America. Under Baird’s leadership, the National Museum expanded from an assortment of curios to a comprehensive and systematically arranged collection, one that delighted scholars and the public alike.

Up until the late nineteenth century the National Museum remained focused on scientific collections as curators labored to document the natural history of the continent and the ethnology of American Indians. That focus began to expand, however, after the Smithsonian acquired a vast collection of cultural material from the Centennial Exhibition of 1876. The arrival of these artifacts, which filled several dozen railroad cars, prompted Smithsonian officials to ask Congress for more space to accommodate them. In 1881 a new National Museum Building (known today as the Arts and Industries Building) opened next door to the Castle. It became a showcase for new collections that included decorative arts, technology, and historical relics. In 1883 the museum acquired a collection of George Washington’s relics and other historical memorabilia that had remained at the Patent Office during the 1858 transfer, back when only scientific material was deemed appropriate for the Smithsonian. With this acquisition the National Museum formally began collecting and exhibiting artifacts related to national history.

Over the next eight decades the museum expanded its national history collections by accumulating political and military relics, costumes, inventions, decorative arts, scientific instruments, and other cultural objects. These objects were exhibited in the National Museum Building and also in special areas in the Natural History Building, which opened across the National Mall in 1910, but they lacked a building to call their own.

Such an opportunity finally arose after World War II. With Cold War tensions running high, many officials keenly felt the need for a museum that would illustrate the “American way of life” and celebrate the nation’s cultural, scientific, and technological achievements. In 1955 President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed a bill authorizing construction of a new Museum of History and Technology as part of the Smithsonian Institution. In 1957 the existing National Museum was officially split into two museums: the Museum of Natural History and the Museum of History and Technology. Curators identified existing collections that would form the basis for the new Museum of History and Technology—armed forces, science and technology, European and American culture, arts and industries, and civil history—and set about collecting more artifacts in these areas to develop exhibitions for the new museum.

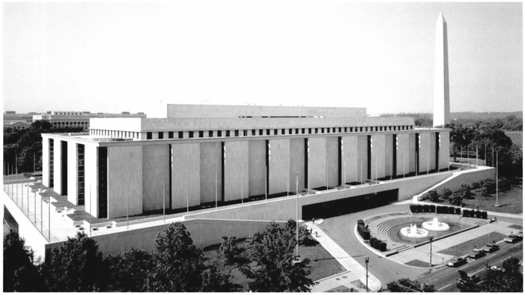

The Museum of History and Technology opened on the National Mall in 1964. In 1980 it was renamed the National Museum of American History to underscore and reinforce its emphasis on collecting, preserving, and exhibiting the material culture of the American people.

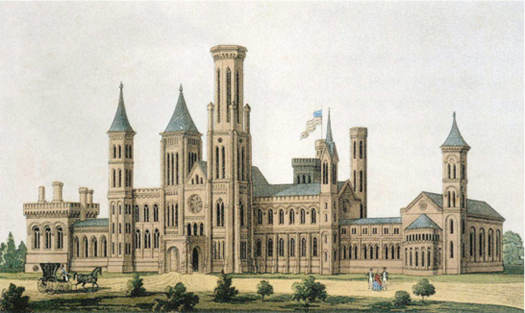

Drawing of the Smithsonian Institution, 1855 (opposite top, left). Designed by the architect James Renwick Jr. and completed in 1855, the building now known as the Castle housed all Smithsonian operations, including the National Museum, until 1881. In addition to exhibit galleries and collections storage, the Castle also contained a library, lecture halls, laboratories, and offices, as well as living quarters for Secretary Joseph Henry and his family. (photo credit 1.1)

A Handbook to the National Museum, 1886 (opposite top, right). By the 1880s, under the leadership of the Smithsonian’s second secretary, Spencer Baird, the National Museum had evolved from an assortment of curios into a comprehensive, systematically arranged collection of anthropological artifacts, natural history specimens, art works, and historical relics. (photo credit 1.2)

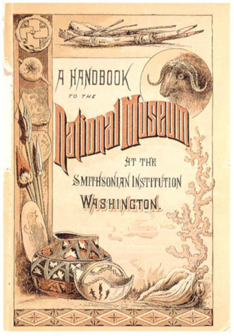

Conceptual drawing of the National Museum, 1878 (opposite center). Opened to the public in 1881, this building contained eighty thousand square feet of exhibitions dedicated to natural history, geology, anthropology, art, technology, and history. It served as the main National Museum building until 1910, when the Natural History Building opened across the National Mall. (photo credit 1.3)

National Museum of History and Technology (now the National Museum of American History), 1972. On its opening weekend in January 1964, the Smithsonian’s new Museum of History and Technology drew fifty-four thousand visitors. Originally planned as a series of fifty exhibition halls dedicated to such topics as farm machinery, railroads, electricity, textiles, period costume, armed forces history, and domestic arts and furnishings, the museum has since undergone many changes in the way it organizes and presents American history to the public. (photo credit 1.4)