By 1870 there was, as described by the historian Michael Kammen, a “new hunger for history” among Americans.15 Popular interest in the past intensified as the country moved away from the war and toward a major milestone, the centennial of its independence. At the Centennial Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia, the celebration of present-day achievements was mixed with a dose of retrospection. Exhibit cases glittered with modern machinery and consumer products and bulged with samples of the land’s bounty—fish, livestock, timber, agriculture, minerals. But fairgoers could also inspect a colonial-style New England cottage, furnished with antiques and costumed interpreters. Nearby, an array of George Washington relics also provided a tangible connection to the Revolutionary War past.

With the public clamoring for more history, the U.S. government stepped in to meet the demand, taking a series of unprecedented steps to define, preserve, and promote a national collective memory. In 1878 Congress appropriated money to complete the Washington Monument, which had languished as a pitiful stump since the original funds ran out in 1855. In 1880 the U.S. State Department removed Washington’s sword and Franklin’s cane from their dusty, crowded case at the Patent Office and enshrined them in its library, along with the original Declaration of Independence and the desk on which Jefferson drafted it. Meanwhile, next to the Smithsonian Castle, construction of the new National Museum Building (known today as the Arts and Industries Building) was nearly finished. Designed to house the carloads of specimens the Smithsonian had inherited from the 1876 Centennial Exhibition, the spacious new building also paved the way for another acquisition that would change the Institution forever. In 1883 Congress authorized the transfer of the final batch of “curiosities” from the Patent Office to the Smithsonian: the relics of George Washington and his fellow founding fathers.

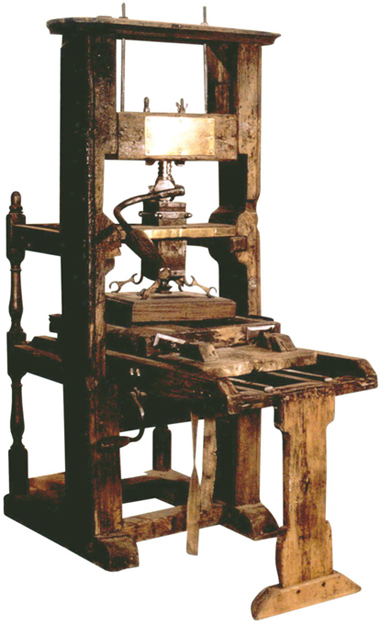

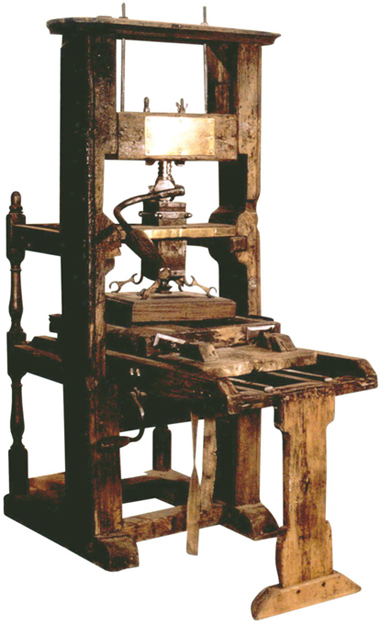

Franklin press, about 1725. The brass label affixed to this printing press in 1833 tells an intriguing story. In 1768 Benjamin Franklin, then the American envoy to England, visited a London printing shop, saw this press, and identified it as the one on which he had worked as an English printer’s apprentice in 1725–26. Although these claims have been difficult to prove, they convinced John B. Murray, an American working in London, to purchase the “Franklin” press in 1842 and ship it to the United States, where for forty years it was exhibited at the Patent Office. In 1847 Murray, looking for a buyer, offered the press to the Smithsonian for $5,000 but was turned down; in 1848 he attempted to raffle it off but could not sell enough lottery tickets. In 1883 the Franklin press, still on loan from Murray, was transferred to the Smithsonian with the Patent Office collection. In 1892, after Murray’s death, his widow offered to sell the press to the Smithsonian for $750. After nearly ten years of bureaucratic wrangling, the Franklin press was officially added to the Smithsonian collections in 1901. (photo credit 11.1)

With this transfer the scope of the National Museum officially expanded beyond natural history and anthropology to encompass the political and cultural history of the United States. The Patent Office memorabilia formed the nucleus of a new curatorial unit, Historical Relics, featuring “personal relics of representative men” and “memorials of events or places of historic importance.”16 Although these were not the first historical artifacts to enter the Smithsonian collections—miscellaneous relics had trickled in since the Institution’s founding—beginning in the 1880s these kinds of objects were accorded new prominence and actively sought by curators. This new interest in history at the museum was accompanied and informed by the rise of history as an academic profession in the late nineteenth century. During this era the first doctoral degrees in history were awarded by American universities, beginning with Johns Hopkins and Yale in 1882. New professional organizations, such as the American Historical Association and the Organization of American Historians (founded in 1907 as the Mississippi Valley Historical Association), were created to promote historical scholarship and set standards for research. The American Historical Association, founded in 1884 and incorporated by Congress in 1889, held its annual meetings at the Smithsonian and deposited its records and publications in the collections.

Samuel S. Cox memorial vase, 1891. Cox, a congressman from New York, headed legislative efforts to create, organize, and expand the U.S. Life-Saving Service. A predecessor of the Coast Guard, it was established in 1871 to rescue victims of shipwrecks by maintaining patrol stations along American shores. In 1891, in honor of Cox’s support, members of the Life-Saving Service presented his widow with this elaborate silver vase, decorated with mermaids, seashells, a life buoy, a portrait of Cox, and a scene of lifesavers rescuing people from the sea. Mrs. Cox presented the vase to the Smithsonian the following year. (photo credit 11.2)

Enshrined in the National Museum, the Washington relics were soon joined by those of other presidents and statesmen as well as soldiers, scientists, inventors, and explorers. In 1922 the State Department gave custody of its most sacred treasures—Washington’s sword, Franklin’s cane, and Jefferson’s desk—to the Smithsonian. By that time the National Museum had become the repository for, in Representative Summers’s words, “the proudest trophies and most honored memorials of our national achievements.”

Curators have continued to cultivate this role up through the present day by collecting and exhibiting the relics of famous Americans. These artifacts tell stories not just about the individuals themselves but also about fame in America. They reflect changing ideas about who is worth remembering and why. Many figures honored by the Smithsonian have remained familiar over the years; their tales have been told and retold, and their possessions retain a magical allure. Others, however, have faded from public memory. Their articles have passed from spotlighted cases into storage drawers, and their stories are all but forgotten, gone with the era that celebrated them.17

Fame may be fleeting, but it can also be recaptured. Once-forgotten individuals may be rediscovered and resurrected by a new generation looking for historical role models whose lives resonate with contemporary concerns and values. Even those who never left the public stage, who have remained permanent fixtures of the national narrative, find themselves reinvented by different groups and new generations. Indeed, such reinvention is key to their survival in popular memory. As Charles Horton Cooley observed in his 1918 essay, “Fame,” a famous figure must appeal “not one time only, but again and again, and to many persons, until it has become a tradition.”18 The image of a famous person must therefore be both constant and flexible; it must be rooted in the past and remain relatively intact over time, but it must also adjust to match the social conditions and tastes of the present.19 The Smithsonian collections thus document not just the fact of fame but also the processes of memory making and remaking, the modification of an individual’s image and story to suit the needs and tastes of the times.