In its early days the Smithsonian Institution was a paradise for the scientist. Its first secretary, the great American physicist Joseph Henry, interpreted the Institution’s mission—the increase and diffusion of knowledge—in purely scientific terms. With its lecture rooms and laboratories, the Smithsonian provided a place for scientists to conduct research and present their findings to the professional community. Indeed, especially with the expansion of government science after the Civil War, the Smithsonian became a critical hub of scientific activity in Washington, D.C., with many distinguished scientists making use of its facilities and contributing to its collections.

Transportation exhibition, National Museum (now the Arts and Industries Building), about 1890. In the late nineteenth century, the National Museum’s technology collections included modes of transportation used by cultures around the world. Dog sledges from Alaska, wagons from New Mexico, elephant saddles from India, and a sled from Norway, complete with a reindeer, were displayed along with steam locomotives such as the John Bull (visible at the lower right). (photo credit 21.1)

But there was more to the Smithsonian than lecture rooms and laboratories. Its collections were not to be kept only in storage drawers for scientists to study, although Secretary Henry might have preferred it that way. The U.S. National Museum was established as a part of the Smithsonian in 1858 to organize collections and display them for the public. And during the second half of the nineteenth century plenty of collections were coming in. Objects brought back by government exploring expeditions—not just flora and fauna but also tools, weapons, and cultural artifacts of indigenous peoples—were transferred to the Smithsonian’s care. Anthropologists and naturalists went into the field and collected numerous specimens from the lands and cultures they studied, while amateur enthusiasts mailed in artifacts found in their own backyards. In 1876 thousands of artifacts left over from the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia were delivered to the Smithsonian.

Photophone invented by Alexander Graham Bell and Sumner Tainter, 1880. In 1880 Bell established the Volta Laboratory in Washington, D.C., to undertake inventions beyond the telephone. That year he and his associate Sumner Tainter deposited at the Smithsonian two sealed tin boxes containing models and documentation of a device they called a photophone, which transmitted sound over a beam of light, and other apparatus. The inventors hoped that the sealed boxes would prove their priority in invention; they did not want to file a patent for fear of giving away secrets that would help competitors. When the boxes were finally opened in 1937, long after Bell’s death, the inventions inside were historical relics, not technological breakthroughs. (photo credit 21.2)

For many years, however, the Smithsonian had precious little space to show off its collections. The exhibit galleries in the Castle were reserved mainly for natural history specimens, so most ethnological artifacts remained in storage, unorganized, because there was no room to display them. With the opening of the new National Museum Building in 1881 (known today as the Arts and Industries Building), curators finally had an opportunity to develop a comprehensive system for classifying and arranging human-made artifacts. They insisted that these artifacts, representing the technology and culture of humankind, should not be displayed in a random fashion but rather presented “in such a logical order that the great truths of human history may be told in the briefest and clearest way,” according to the National Museum’s 1898 annual report. Just what that “logical order” was proved a subject of endless debate among these early scientist-curators; it was “the all-important question.”

More than any other individual, George Brown Goode helped shape the National Museum. Although by training a biologist, he was also a historian of science, genealogist, and, most important, curator and museum philosopher. Twenty-two years old when he joined the Smithsonian in 1873, he was put in charge of the Smithsonian exhibits for the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia just three years later. He also organized the Smithsonian exhibitions at many other fairs and was responsible, as assistant director of the National Museum, for installing exhibits in the Smithsonian’s new National Museum Building in 1881. During the time he was at the Smithsonian, from 1873 until 1896, its collections grew from two hundred thousand items to more than three million. He was a true believer: “The degree of Civilization to which any nation, city, or province has attained,” he wrote,” is best shown by the Character of its public museums and the liberality with which they are maintained.”2

Goode and his associates believed there were two basic ways to organize the Smithsonian collections. The first was geographical or ethnographical—the European method. Collections were grouped according to their tribal, national, or ethnic origin, thus transforming the museum into a miniature world. Moving through the museum, the visitor could “make his studies pretty much as he would make them in traveling from country to country.” The second organizational scheme told the story “not of tribes or nations and their connection with particular environments” but rather the story of the “development of the race along the various lines of culture progress, each series beginning with the inceptive or lowest stages and extending to the highest.”3 Goode, as director of the National Museum in its new building, argued for this mode of display. Exhibits would be organized not by geography but by a functional or teleological approach, using classification schemes similar to the ones used in natural history. Like animals or plants, cultural artifacts would reflect evolution. Such was a biologist’s way of thinking about history.

In the scientific jargon of the day, these exhibits were called synoptic series. (A synopsis is a table, chart, or exhibit that gives a general overview of a subject.) Each synoptic series “progressed” from the most “primitive” device to a recent example of a machine that performed that function. Techniques for making a fire, for example, ranged from a fire saw from Borneo and a lens for focusing sunlight from “Ancient Greece” (as the exhibit label read) to contemporary phosphorus matches and an electric gas lighter. A series of spoons included shells used as spoons in Mexico to a carved horn spoon from Alaska to a modern pewter spoon from England. Musical instruments progressed from a conch shell to a cornet. In 1898 the National Museum had on display eighty-one different synoptic series.

The focus on progress was apparent in every aspect of the collections. The instructions that Samuel Langley, Smithsonian secretary from 1887 to 1906, sent to his British agent in 1890 outlined the goal: “Make a collection of watch-movements calculated to show the principal steps in watch making from the beginning to comparatively recent times.… Only such are wanted as … are typical of the history of the watch, and calculated to instruct the public rather than to be of curious or professional interest.”4 Sylvester Koehler, curator of graphic arts from 1886 to 1900, wrote that “the technical process employed in the representation becomes the first thing to be considered, and the history of engraving consists in the record of the steps by which the various processes approached perfection.”5

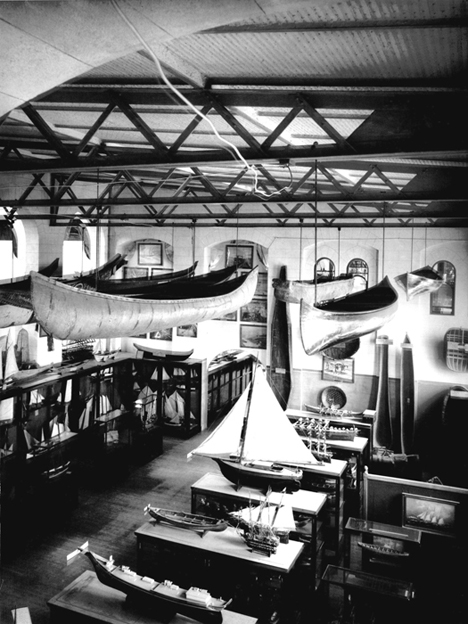

Boat Hall, National Museum, about 1890. Early National Museum collections combined technology and ethnology, documenting the inventions of various cultures and countries. The story of water transportation was presented through a comprehensive display that included Native American canoes, fishing boats from the West Indies and other parts of the world, and a series of models illustrating the evolution of nineteenth-century American fishing vessels. (photo credit 21.3)

Synoptic series representing the invention of spindles, shuttles, and looms, National Museum, about 1890. This exhibit case depicting the history of textile manufacture is a typical synoptic series. On the far left in each of the three horizontal series is the most “primitive” example of the type. On the far right is a recent invention in the field from contemporary American industry. Looking from left to right, museum visitors could see each of the major advances, with examples drawn from China, Central America, Peru, Tibet, Finland, Germany, and the United States. Smithsonian curators believed that this kind of arrangement showed a fundamental truth about the progressive nature of technology while bringing together related artifacts in one case. (photo credit 21.4)

Goode, trained as a biologist but an ardent amateur genealogist immensely proud of the “purity” of his Anglo-Saxon ancestors, thought this scheme made good sense. It presented an evolutionary, almost genealogical, notion of progress: “Objects of a similar nature being placed side by side, musical instruments together, weapons together, &c., [are] arranged in such a manner as to show the progress of each idea from the most primitive type.”6 Each specimen in the synoptic series stood “not as an isolated product of activity, but for an idea—a step in human progress … and the order is such as to suggest to the mind the broader truths of human history.” In a glance a visitor could capture “the development of human thought and the gradual expansion of human interests.”7 The historian Arthur Molella calls this scheme a “progressivist vision of technical evolution.”8

Tools for working leather and making shoes, manufactured by Wm. H. Horn and Brother of Philadelphia, 1884. World’s fairs and expositions gave companies an opportunity to advertise their latest products and technologies, and the Smithsonian often helped collect and arrange objects to represent U.S. industries at these events. The Horn company sent a complete line of brand-new leather-working tools to the Smithsonian for inclusion in an exhibition at the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition, held in New Orleans in 1884–85. (photo credit 21.5)

Not all of the National Museum’s exhibits were in the synoptic style, however. Where there were duplicates of material for display, the museum created exhibits arranged by geography as well. By 1889, in fact, Goode described the museum as arranged by “a double system.”9 Otis Mason, the first curator of the museum’s ethnology department, described his way of presenting both schemes: “Now, in a museum properly constructed it is possible to arrange the cases in the form of a checkerboard, so that by going in a certain direction the parallels of cases represent races or tribes or locations. By inspecting the same cases in a direction at right angles to the former, the visitor may study all the products of human activity in classes according to human wants.”10 Goode eventually decided that all of the museum’s cases should be designed so that they could be easily moved from one organizational scheme to another. (This approach was not only ideologically useful but also practical: it allowed the cases to be rolled into the lecture room for lectures and squeezed more tightly together when space was needed for new collections.)

The debate over the proper arrangement of the cases, by technological evolution or by region, was more than a matter of personal whim or academic concern. Institutional politics played a role, as with all museum exhibits, but there were bigger issues at stake. In this instance, exhibit organization was a direct reflection of beliefs about the nature of civilization—beliefs about invention, technology, progress, and humanity. Smithsonian exhibits reflected widely held ideas. “Many intellectuals,” writes the historian Steven Conn, “regarded museums as a primary place where new knowledge about the world could be created and given order.” The world outside the museum might seem “increasingly chaotic and incomprehensible.” But within its walls, “rationality and order could be maintained.” Walking down the aisle of brightly-lit glass cases, museum visitors would learn that nature had an essential order, that technology evolved from simple to complex, and “that design could be revealed, understood, and controlled by rational science and scientists.”11 Americans were accustomed to “reading” the “language” of the artifacts around them and would find the rhetoric of the displays easily understandable.12

The foremost proponent of organizing the National Museum’s exhibits by synoptic series and the curator who offered the fullest explanation of the idea was Otis Mason. A scholar of Mediterranean archaeology, he had taught anthropology and other subjects at Columbian Academy (now George Washington University) in Washington, D.C. In 1869 Mason came to work at the Smithsonian, becoming the full-time curator of ethnology in 1884. Here he developed his theories about the importance of invention, building a series of exhibits that showed the steps each civilization passed through as it rose “from savagery to barbarism to civilization.” He believed that inventions should be classified, like natural creatures, along lines of evolution. “Anthropology,” he wrote in 1899, “is the application of all the methods of natural history to the study of man.”13 This dependence on biological models made good sense at the Smithsonian of the 1880s and 1890s, when scientists were in charge and set the museum’s tone—and its budgets.

Invention, as Mason saw it, was the story of the progress of the human race. He defined invention broadly, as a new implement, improvement, substance, or method in almost any field: “not only mechanical devices … but in the processes of life, language, fine art, social structures and functions, philosophies, formulated creeds and cults.”14 If the history of humankind was the history of invention, the inventor was the most important force in civilization. Inventors of a more “primitive” race might be inventing something already invented elsewhere, as they moved along the common path of progress and civilization, but they were nonetheless among the heroes of humankind. Mason rejected the myth of a few heroic inventors; to him all inventors were heroic.

A frequent subject of debate among nineteenth-century scientists was the creation of the human races, whether they descended from one common ancestor or were created separately. Mason believed the synoptic series demonstrated that the human mind everywhere produced the same inventions, that all races adhered to the same path of progress. The story of invention, Mason believed, traced all cultures back to a single source.

At the same time Mason thought it important to rank cultures on the basis of their inventiveness. Synoptic series could be read to show not just the overall progress of the human race but also the relative progress of the races. Indeed, synoptic series inevitably reinforced notions of racial hierarchy. “The Mediterranean race,” Mason wrote, “is the most mechanical of all.… The Semite is much less so. The Mongolian is, perhaps, more ingenious with his hands. The Africans and the Papuans are more mechanical than the brown Polynesians; the Eskimo than the red Indians; and the Australians are the least clever of all.” Yet even the Australians, Mason was quick to proclaim, had inventors among them. The boomerang, although an invention “of a humbler sort,” had a history just as the rifle or the locomotive did. “And there is not a patent office in the world,” he added, “that would refuse to grant them” a patent on it.15

Howe pin-making machine, about 1840. In 1910, when the son of a founder of the Howe Manufacturing Company offered the Smithsonian the first practical machine for making pins, curators jumped at the opportunity. The machine would “add a most interesting feature to the industrial collection,” they noted, and would be a good first step in the “effort to build up a creditable collection to illustrate [the arts and industries], bringing out more strongly the practical side of the Museum.” (photo credit 21.6)

Gender, like race, was a key element in Mason’s scheme of “culture progress.” Women played a role not unlike the primitive races: they laid the foundations on which others built. “In that continental struggle called Progress or Culture,” Mason wrote, “men have played the militant part, women the industrial [that is, productive] part.” Mason studied “modern savagery” to understand “the activities of our own race in primitive times.” “This teaches us,” he wrote, “that women were always the first house builders and furnishers … the first clothiers.… They invented all sorts of … things employed in the serving [cooking] and consuming of food.…”16 Woman’s primitive work made possible man’s more advanced work.

Technology exhibits at the Smithsonian reflected not only ideas about race and gender but also the politics of the day: the specter of communism and working-class radicalism. Mason and his colleagues assumed that invention and individualism went hand in hand, that inventors invented because they were rewarded for their inventions. In The Origins of Invention: A Study of Industry among Primitive Peoples (1895), Mason argued that “primitive” tribes were “kept behind in the march of civilization” because their cultures were not individualistic enough: “One of the greatest hindrances to more rapid progress among savages through the multiplication of inventions is their communistic system, their tribal intelligence and volition.”17 Mason saw individualism and self-interest as essential elements of invention and invention as the essential element in the progress of civilization. Visitors to the museum would certainly have gotten that message.

Fear of radicalism was also implicit in another way. General Pitt Rivers—founder of the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, England, which was also organized by synoptic series and was a major influence on the Smithsonian—was explicit about the meaning of evolution in technology. According to Rivers, the sequential arrangement of a vast variety of artifacts proved that nature changes by slow evolution rather than by radical “jumps.” An ignorance of this history meant that the working class was “open to the designs of demagogues and agitators.” Visiting his museum and seeing the slow, evolutionary nature of change in civilization—proof through objects of the “law that Nature makes no jumps”—would encourage the working class to be wary of “scatter-brained revolutionary suggestions.” The Smithsonian curators never ascribed such political power to their synoptic exhibits, which nevertheless carried the same message.18

Although Goode and Mason believed strongly in the synoptic style, the fruitfulness of analogies from evolution, and the universality of invention, their anthropological theory would not win out in natural history museums. The simpler style of organizing things by where they came from—generally by nation or tribe—was to triumph, partly because it provided the types of exhibits visitors most wanted to see.

Unlike Otis Mason, Franz Boas is still a well-known figure to anthropologists. Considered the founder of professional American anthropology, Boas worked at the Smithsonian as a consultant in 1894 and 1895 and then for several years at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City before abandoning museums for an academic career. He was a primary proponent of organizing ethnographic materials by tribe to emphasize the effects of the environment. Mason’s model was basically biological; Boas argued for a historical and environmental model. In 1887 Mason and Boas exchanged views in a series of articles in the journal Science. Boas stressed uniqueness and individuality; Mason, system and unity. Mason saw the work of evolution everywhere, while Boas believed in cultural relativism and pluralism. Whereas Mason looked at generalities, Boas argued that each specimen needed to be studied in its own historical and environmental context. “Classification,” Boas insisted, “is not explanation.”19

Boas effectively demolished Mason’s argument on logical grounds. Just because different cultures produced similar artifacts does not mean they had the same causes; analogy was not proof. Synoptic series, Boas argued, revealed more about the mind of the curator than the mind of the people being studied. For Boas, there was a larger principle at stake, too:

It is my opinion that the main object of ethnological collections should be the dissemination of the fact that civilization is not something absolute, but that it is relative, and that our ideas and conceptions are true only so far as our civilization goes. I believe that this object can be accomplished only by the tribal arrangement of collections. The second object, which is subordinate to the other, is to show how far each and every civilization is the outcome of its geographical and historical surroundings.20

Boas was primarily concerned not with general principles of technological or cultural development but with showing that cultures were different and that different cultures developed differently. He hoped to explain why those cultures developed—not by looking for general rules but by understanding each individual culture.

Although Mason never abandoned his theoretical arguments—and his protégé Walter Hough, who succeeded Mason as head curator of the anthropology department in 1908, continued to add to the synoptic series through the 1920s—Boas’s arguments won the day. The Smithsonian started to add exhibits showing individual tribes. Life groups, or dioramas, were immensely popular, especially in the exhibits staged by the Smithsonian at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893.21 Concern for the visitor, the historian Ira Jacknis suggests, helped push both Mason, at the National Museum, and Boas, at the American Museum in New York City, away from their theoretical positions and toward a similar attitude toward display. Mason included life groups, while Boas, realizing that his audience was the general public, not anthropologists, added exhibits of “interest to the tradesman … showing the development of the trades of the carpenter, the blacksmith, the weaver, etc. in different cultural areas.”22

While academic anthropology would leave Mason’s naive evolutionary notions behind, aspects of his ideas would continue to shape Smithsonian exhibits for the next century. Exhibits can support only a fairly simple, straightforward narrative, and the concept of progress provides just that simple story. The myth of the autonomous progress of technology—proceeding according to its own evolutionary logic, shaping human culture but unshaped by it—would continue to provide the story line in Smithsonian displays. The theoretical base that Goode and Mason had built would disappear, but their ideology of progress would remain.

Smithsonian exhibit, Louisiana Purchase Exposition, St. Louis, 1904. At most of the major world’s fairs held in the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Smithsonian coordinated the U.S. government’s exhibits and prepared displays of its activities and collections. In these exhibits the whole world was put in order, with ethnography, religion, and technology displayed according to carefully thought-out ideas about progress. The Smithsonian’s exhibit at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition included the Langley aerodome, a model of a whale suspended from the ceiling, natural history exhibits, archaeological artifacts, and industrial machines. (photo credit 21.7)