Otis Mason’s Origins of Invention concluded with a paean to the primitive inventors who built the foundation for modern technological society: “The whole earth is full of monuments to nameless inventors.”23 But by 1895, when the book was published, the argument over display by synoptic series or by race or region was pretty much over, partly because of the triumph of Franz Boas’s ideas and partly because the public was demanding livelier exhibits, especially dioramas. But for the story of the history of science and technology at the National Museum, another reason was even more important. Inventors and engineers had begun to gain prominence in American society, and curators were not interested in nameless inventors. Instead, they wanted to celebrate the “men of progress” who were transforming America.

Electromagnetic telegraph exhibit, Arts and Industries Building, 1930s. Although Samuel F. B. Morse and Joseph Henry, the first secretary of the Smithsonian, both claimed to have invented the telegraph, by the 1860s Morse was generally given credit and installed in the pantheon of American inventors. This exhibit included the first telegraph receiver, donated by Western Union to the Smithsonian in the 1890s; a portrait; and some of the many medals Morse received for his invention. (photo credit 22.1)

J. Elfreth Watkins was one of these men of progress. An 1873 graduate of Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania, with a degree in civil engineering, he had gone to work as a construction engineer for the Pennsylvania Railroad. After an industrial accident cost him a leg, the railroad gave him a desk job. Becoming interested in the railroad’s history, he published a history of one of its early lines on its fiftieth anniversary in 1884. Later that year the railroad allowed Watkins to work part-time at the Smithsonian as an honorary—that is, unpaid—curator of steam transportation. One of his first actions was to convince the Pennsylvania Railroad to transfer to the Smithsonian the John Bull, the “oldest complete locomotive in America.”

The John Bull locomotive on its way to the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, 1893. The Smithsonian agreed to loan the John Bull, which it had acquired from the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1884 (see this page), back to the railroad for display at the World’s Columbian Exposition. The trip from Washington, D.C., to Chicago was a great public relations success; brass bands greeted the locomotive and its train at stops ail along the way. At the fair thousands of visitors rode in cars pulled by the antique engine. (photo credit 22.2)

The railroad industry liked seeing its history alongside the other national treasures at the Smithsonian. In the 1880s the railroads were the most powerful—and the most hated—corporations in the country. Watkins encouraged them to see the museum as a valuable public relations opportunity, a place to preserve and honor “the history of the Railway and Steamboat, the greatest civilizers of the century.” In 1886 more than nine hundred railway officials petitioned Congress to add funds to the Smithsonian’s budget for organizing a “Section of Steam Transportation” at the National Museum.24 And railroad officials, used to flexing their muscles on Capitol Hill, knew how to get their way: “Under our system of Government, our representatives sometimes need a little pushing,” is how one railroader put it.25 Push they did, and Congress granted the extra funds to put Watkins on the Smithsonian payroll.

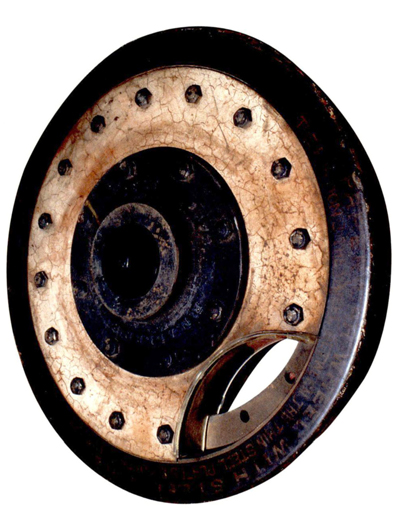

Wheel from the DeWitt Clinton locomotive, 1831. In 1891 Smithsonian curators collected this early American railroad relic—a wheel from, according to the National Museum’s 1891 annual report, the “first engine placed into service on … the oldest railway in the state of New York.” On the wheel is inscribed “First Trip, August 9th 1831.” (photo credit 22.3)

As curator, Watkins did the railroad industry proud. He sought out and brought to the National Museum both the relics of early American steam transportation and the latest technological advancements of the railroad industry. He wrote articles and books, including a history of railway track and a history of the Pennsylvania Railroad. He organized transportation displays at national and international fairs, such as the Ohio Valley Centennial Exposition in 1888 and the World’s Columbian Exposition five years later, displays that in turn served as a basis for Smithsonian exhibits. Moreover, he continued to work on contemporary issues of interest to the railroad industry.

Watkins’s collecting had far-reaching impact. He collected some of railroading’s most precious relics: bits and pieces of pioneer locomotives. In addition to the John Bull, he found an original wheel of the DeWitt Clinton, a cylinder from the Pride of Newcastle, and the bell from the Rahway. He sent one of his assistants to explore the area around Honesdale, Pennsylvania, where the Stourbridge Lion had operated, and acquired the boiler and walking beam of that “first locomotive in the Western Hemisphere to run on a railroad built for traffic.” (The Stourbridge Lion had little technological significance and was a practical failure, but as an American “first” it was enormously important to Watkins and the railroad history enthusiasts of his day.) In the 1880s, when Watkins began collecting, the first generation of railroaders was still alive. Watkins sought out people like Isaac Dripps, the mechanic who had assembled the John Bull, and pumped him for details about the early days of railroading.

Allen Company paper car wheel, 1884. Invented by Richard Allen, a locomotive engineer, this railroad wheel featured a compressed paper disk that supposedly provided a smoother and quieter ride than cast-iron wheels. It was first displayed at the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition in New Orleans in 1884–85 and collected by the Smithsonian four years later as an example of contemporary railroad technology. (photo credit 22.4)

In addition to historical relics, Watkins also collected the cutting-edge technology of his day. In 1889 David G. Weems, a Washington, D.C., inventor, built an electric locomotive that set a speed record; within a few years Watkins had acquired it for the Smithsonian. Some of Watkins’s contemporary collections looked a lot like advertising. In 1888 the Allen Paper Car Wheel Company donated a cut-away version of its paper car wheel, originally built for the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exhibition, held in New Orleans in 1884–85. The Pullman Palace Car Company, operators of a fleet of luxurious sleeping cars, were the largest users of the Allen wheel and great promoters. “Early notices of Pullman cars,” writes the historian John White, “always seem to mention the wonderful paper wheels which silently and securely transported the car and its occupants across the country.” And now they were on display at the Smithsonian.26

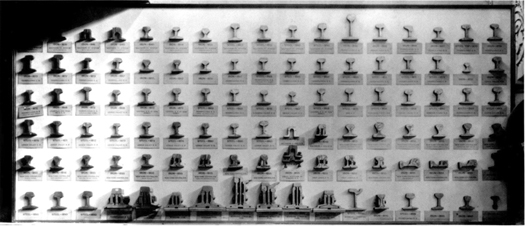

Rail track cross sections, National Museum, about 1905. Curator Watkins turned the anthropologist’s synoptic series into a history of engineering. Rather than a progression from the most primitive type to the most advanced, his version of a synoptic series showed variations of modern types. (photo credit 22.5)

Although Watkins adopted some of the theories of invention that Goode and Mason had developed, especially in the “study series” he created to illustrate aspects of the technological evolution of the locomotive, he applied these theories in a very practical way. He collected like an engineer, not an ethnologist. He celebrated particular inventors, not anonymous invention. And he went beyond invention to celebrate the engineers, innovators, businessmen, and entrepreneurs who applied invention in the real world. Watkins was not a philosopher of collections, although he was a true believer. “I believe it true,” he wrote, “that history perpetuated by things is more authentic, more valuable, than history recorded in words.”27 In his eyes railroad relics were as valuable in their own way as George Washington’s sword or Ulysses Grant’s medals. And early railroaders were national heroes, technological counterparts to the presidents and politicians enshrined in the Smithsonian’s history collections.

Through Watkins’s efforts, the story of technological progress told at the Smithsonian became primarily a story of national progress. Unlike his scientist predecessors, Watkins focused on the American story, using the English locomotives on which American ones were based as a preamble and paying little attention to primitive forebears. Watkins quite consciously tied technological progress to the progress of American democracy. Technology, he wrote, not only improved the “world’s material progress” but especially benefited America: “Nowhere upon the face of the globe does mankind partake of the benefits of personal liberty to as great an extent as in free America. Without the railway and the telegraph … this enviable condition could not have been reached.” The railroad in particular was responsible for bringing the country together: “We have become one people—speaking one language, actuated by a common impulse ‘with malice toward none and charity for all.’ ” Watkins exalted the democratic power of technology, declaring that “the birth of the steamboat and locomotive were coeval with the establishment and first growth of this great Republic, and that by them were secured eternal Liberty! Union!! Peace!!!”28

Steam engine and boiler designed by John Stevens, 1804. John Fitch, James Rumsey, Robert Fulton, and John Stevens all claimed credit for the first successful American steamboat, and material relating to each of their boats has been saved as relics at the Smithsonian. This engine and boiler, from Stevens’s Little Juliana, represent the first successful use of a screw propeller. The “oldest surviving steam power plant built in America,” according to its exhibit label, Stevens’s engine was displayed at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 and then sent to the Smithsonian. (photo credit 22.6)

Watkins was only one of the new breed of technology specialists at the National Museum. Joseph William Collins, a former Gloucester fishing-schooner master, applied his knowledge of fishing boats to build the National Watercraft Collection, begun in 1884. He had helped set up exhibits on American fisheries at international expositions and believed that half-hull models were a good way to illustrate “the progress of ideas and enterprise.”29 Thomas W. Smillie, hired as the Smithsonian’s first official photographer in 1870, began to document photographic history and contemporary photography in the 1880s by collecting images and equipment. In 1888 he acquired Samuel F. B. Morse’s daguerreotype camera, the first used in America. In 1917 Frederick Lewton, a curator of textiles who had temporary charge of the medical collections, urged the American Pharmaceutical Association to preserve at the Smithsonian the “many unique and irreplaceable objects” illustrating the early history of American pharmacy.30 George Colton Maynard, curator of the electricity collections from 1885 to 1918, had been chief operator for Western Union in Washington, D.C., and had organized the city’s first telephone exchange system. He used his connections to obtain material from Western Union, American Telephone and Telegraph, and inventors and engineers.

Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone prototypes, 1876. Prototypes—working models that allow an inventor to think through the problems of bringing an idea to life—document the inventive process. In 1908 Bell presented to the Smithsonian a collection of his early telephone apparatus. Included were the 1876 liquid transmitter that relayed Bell’s famous command to “Mr. Watson,” and these devices, made a few months later, which he showed off at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. (photo credit 22.7)

This next generation of curators had even less interest in the inventions of “uncivilized” peoples than did Watkins. Maynard proclaimed himself uninterested in “man the handicrafter” and focused instead on the artifacts of “civilized man,” “man the mechanic.”31 For these new curators, the step from historic inventions to contemporary industry was a small one. As industry increased in importance and complexity and as technology became more removed from everyday experience, it seemed appropriate to provide more space for contemporary industrial displays.

Indeed, companies and trade associations provided the Smithsonian with numerous industrial exhibits during the early twentieth century. In 1905, for instance, the Libbey Glass Company of Toledo, Ohio, donated a display showing off its latest industrial techniques and products. Examples of modern American ceramics and glass, representing the application of industry to artistic pursuits, were eagerly sought by curators who considered it their mission “to educate the public taste, and to … forward the growth of the arts of design.”32 By 1924 the Smithsonian’s annual report noted with pleasure that national trade associations “are becoming more appreciative of the National Museum as a means of informing the American public of the importance and scope of great American industries.” The Rubber Association of America donated specimens to show rubber production, rubber manufacturing operations, and the role of rubber in communications, transportation, power, firefighting, clothing, health, home, toys and sports, and warfare. The American Brush Manufacturers’ Association donated a representative series of animal fibers and specimens of brushes made from them. The National Boot and Shoe Manufacturers’ Association and the United Shoe Machinery Corporation donated 119 specimens illustrating the production of woman’s shoes. Displayed at the National Museum, these collections celebrated the achievements of modern American industry.33

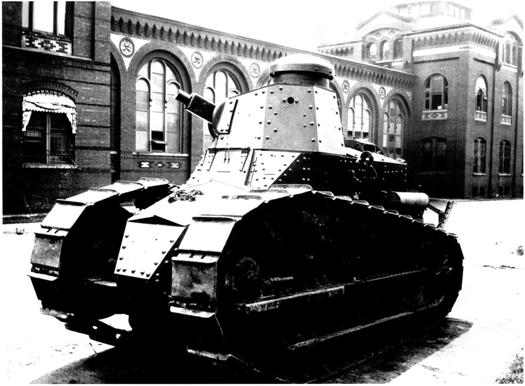

During World War I, the National Museum created a number of exhibits at the request of the U.S. War Department, Red Cross, and U.S. Food Administration. Visitors could learn how to knit and crochet articles of clothing for soldiers, discover new ways to use fats and oils, and get advice on conserving food. Experts from the U.S. Department of Agriculture built a model kitchen and gave demonstrations for housekeepers and war workers. Lectures included “Food for the Family on $2 per Day,” “What Becomes of the Consumer’s Dollar?” “What Do You Give Your Children to Eat?” and other equally pragmatic topics.34 Meanwhile, the lobby and exterior grounds of the new Natural History Building were filled with a large collection of World War I artifacts, including weapons, uniforms, and captured enemy equipment—an immensely popular exhibit. (At the start of World War II, some of the captured German weapons were melted down for the war effort, yielding one hundred tons of steel.)

Glass platter, Libbey Glass Company, about 1904. From an exhibit illustrating the manufacture of glass, this platter depicts the process of glass cutting and engraving. The exhibit demonstrated the links between art and industry as well as “national pride,” noted the Libbey Glass Company of Toledo, Ohio, which presented the platter to the Smithsonian in 1905. (photo credit 22.8)

The National Museum of the 1910s and 1920s was, in many respects, a place dedicated to progress. It educated the public not only about the history of science and technology but also about how modern inventions and industries could benefit Americans in their own lives. Its exhibits embodied the spirit of the Progressive Era, a time of widespread education and reform efforts aimed at improving how Americans lived, worked, and played. By applying the lessons of science and technology to daily life, many reformers believed that the social problems of crime, poverty, disease, overcrowded cities, and unsafe working conditions could be alleviated, thus enabling the nation to progress to a new level of health, wealth, and happiness. Consider this 1925 display, a model village to “illustrate in allegory the never-ceasing struggle of health against disease”:

Allied tank outside the Arts and Industries Building, about 1920. After World War I the Smithsonian collected war artifacts and exhibited them in and around the Arts and industries Building and in the rotunda of the Natural History Building. The Smithsonian’s 1919 annual report underscored the importance of “graphically illustrating the military, naval, and aerial activities not only of our own side of the conflict but of that of our opponents as well.” (photo credit 22.9)

A section of a village is shown with a wall obstructing the entrance of diseases represented as beasts, from a dark and gloomy forest. This model emphasizes the fact that disease prevention is everybody’s work, and that each individual owes it to himself and the community to render active assistance in this struggle to increase the life span and make the world a better place in which to live by complying strictly with all health laws and regulations.35

By dispensing advice on hygiene, housekeeping, and nutrition, demonstrating new and improved industrial machinery, or illustrating the arsenal of modern weapons developed to fight America’s enemies—be they germs or Germans—the Smithsonian offered visitors abundant evidence that technological progress was indeed making the world a better place.