The stories that visitors took home from the new Museum of History and Technology were not all that different from those that Carl Mitman had wanted to tell or, for that matter, those that visitors took away from the synoptic series. Visitors saw technological objects arranged with similar objects. They saw chronological order. They saw progress, either explicit or implicit. Because there was little historical context, it would be difficult for them to see anything other than technological change: progress, improvement, evolution. And technological progress implied social, political, and economic progress. Museum exhibits showed—at least they implied—that everything was getting better for everyone.

After all, the artifacts were still, for the most part, arranged to emphasize the technological story. Artifacts organized in technological categories do that. Each machine is more powerful, more productive, or simply newer and shinier than those before. They tell a story of progress. John Staudenmaier, a historian and philosopher of technology, makes the distinction between “clean exhibits” and “messy exhibits.” Clean exhibits, with their “sanitised aesthetic,” he argues, define contemporary technical museum practice. They avoid the messy political side of technology, suggesting a “vision wherein all victims are temporary down payments for future blessings and all critics those who fear to face the future.” And they ignore “the essential ambiguity of every technical endeavor” by avoiding “questions of power and exclusion, of who wins and who loses.” Staudenmaier calls for exhibits that leave visitors “with a deeper sense of the essential humanity of the technological endeavour, aware that technological choices reflect the full range of humanity, intelligence and stupidity, nobility and venality.”73

Roadside billboard mock-up produced by the Cunningham and Walsh advertising company for Texaco, mid-1950s. Cunningham and Walsh, now a subsidiary of N. W. Ayer, was one of the first American advertising agencies. The Smithsonian began collecting material from N. W. Ayer and related firms in 1975 and continues to receive donations, such as this mock-up, acquired in 1996. An inside glimpse into the world of advertising since 1849, the N. W. Ayer Advertising Agency Collection shows how the mass media has marketed technology as a consumer product. (photo credit 26.1)

To tell this messy story would mean looking at more than firsts, improvements, progress. It would require that curators ask different kinds of questions. In recent years curators have argued that the only way to overcome the obvious messages of the machinery is to focus on other stories. Exhibits should use technology to tell stories about politics or people first and technology second. Artifacts must be placed in a human rather than a technological context.

To tell historical stories, curators had to go beyond simply collecting the object. They had to collect a complex story around the object. And in recent years curators have been doing just that. They have filmed machines in action. They have interviewed designers, managers, and workers. They have collected production drawings, prototypes, work records, and even financial information about the companies where the machines were used. All help tell a more complicated story. It might still be, in technological terms, a story of progress. But it is a much more complex and interesting story of progress than simply one machine following another. It is a human story of social and cultural as well as technological change.

Auto plant worker’s badge, hat, and notebook, 1989. Identification badges and hats were standard for workers at the New United Motor Manufacturing (NUMMI) plant in Fremont, California, one of the first factories in the United States to adopt Japanese mass-production techniques. In 1989 Smithsonian curators traveled to the plant to collect artifacts for an exhibit on the history of work and management. To decide whose uniforms would be donated to the Smithsonian, the company held an employee essay contest on the topic of teamwork; the winners were Judy Weaver, from the engineering department, and Rick Madrid, from the quality control department. These artifacts were donated by Madrid. (photo credit 26.2)

Delegate’s badge from American Federation of Labor convention in Kansas City, Missouri, 1898. Telling the story of work means telling the story of unions too. in 1989 the son of the labor union leader John Brown Lennon donated more than one hundred badges and other memorabilia from labor organizations to the National Museum of American History. This collection joined several large collections of labor memorabilia acquired in the late 1980s. (photo credit 26.3)

In the 1980s a new wave of exhibit ideas swept the museum community. The new social history—history “from the bottom up”—had found a favorable reception in history departments in the 1970s and eventually in history museums, especially in exhibits about everyday life. Industrial, scientific, and technological exhibits resisted a bit longer, but in the 1980s and 1990s these collections and exhibits began to reflect a more historical, less technological view. They began to address, in Staudenmaier’s terms, a messier story.

Machinist’s tool chest, about 1949. John Emile Lovret, who went to work at age fourteen to support his family, became a skilled machinist and inventor, working for various companies before setting up his own shop in New York. He decorated his tool chest with family photos and a playing card he considered his good-luck charm. In 1998, when ill health forced him to close his shop, his daughter contacted the Smithsonian. Curators chose to collect this chest because “for a machinist the tool chest is the embodiment of the person.… Mr. Lovret is important not because he is the first, the only, or the best but because he provides us anecdotes to tell the common, the usual, and the ordinary.” (photo credit 26.4)

Augusta Clawson’s welding mask, 1943. In 1943 Augusta Clawson, a recent Vassar graduate and specialist with the U.S. Office of Education, was given an undercover assignment at the Swan Island Shipyard in Portland, Oregon, to learn why women recruited as welders were quitting as soon as they finished their training. Her two months’ experience as a welder became the basis of her book Shipyard Diary (1944). In 1988 Clawson donated her welder’s face mask, photographs, and copies of her reports to the Smithsonian, where they have been used to help tell the story of women war workers. (photo credit 26.5)

One way the new exhibits did this was to look at the story of a single machine in great detail. The object’s story was told on its own, not as a representative of a type or as part of a story of technology. So a sawmill would not be shown with other sawmills but rather with other artifacts that told the story of that particular sawmill. Where was it located? Who owned it? Who worked there? What did it produce? Who bought the product? The artifact becomes its own story, not a bit player in the story of technological advance. It is surrounded by the messy details that tell a social story.

Furnace salesman’s kit, 1920s. Walter G. Bennett used this demonstration kit to sell Holland warm-air furnaces to homeowners during the 1920s. In 1981 Bennett’s son offered his father’s kit to the Smithsonian. Appropriately, his letter began with a sales pitch: “Has the Museum ever commemorated that great American institution, the salesman?… I hope you can use this kit; it would please me to know that some part of my father’s life was made a part of this country’s history.” (photo credit 26.6)

A related way that the new breed of exhibits got beyond the machines was to examine not the technology or even the effects of technology but rather the shaping of the technology. How did the machines get to be the way they were? Asking this question—and answering it with information about labor, politics, and work—meant that the machines were no longer being taken for granted. Instead of machines begetting machines, machines develop within a social and cultural setting. Society and culture, not machines, were granted the privileged position. In recent years technological collections have begun to tell stories of work and management, business, and economics.

Work is a topic that has always been closely related to technology, but for many decades it was rarely addressed at the Smithsonian. The stories of people who actually used the machines received less attention than stories about the machines themselves. Yet machines are shaped by the work that people perform with them and by ideas about the nature of work. Industrial machinery in particular takes on political and cultural significance when considered from the perspective of the workers who used it on the factory floor. As curators became more interested in the stories of workers, objects in the collection acquired new meanings. Tools told the story not only about new technology but also about the development of occupational skills and identity. Industrial machines invited questions about worker health and safety, the rules and culture of the workplace, and the relationship between human and machine. The National Museum of American History’s role as a palace of progress began to mesh with its role as a mirror of America.

Vials of polio vaccine, 1954. Contemporary medical advances have always been of interest to the curators of the Smithsonian’s medical collections. These vials of poliomyelitis vaccine were produced for the first national trials in 1954. On April 12, 1955, the new vaccine was declared safe and effective, and its developer, Dr. Jonas E. Salk, became an international hero. Twelve vials of the trial polio vaccine were donated to the Smithsonian between 1956 and 1958 by the National Infantile Paralysis Foundation and the laboratories that manufactured the vaccine. (photo credit 26.7)

Business and economics also became an explicit part of the technological story. Traditionally, business history was written from business archives—letter books, corporate minutes, payroll accounts—and the National Museum of American History began to collect these. But business has a material culture too. Marketing and advertising, the materials that link technology and business to consumers, became a strength of the museum’s collections with the acquisition of the Warshaw Collection of Business Americana and the N. W. Ayer Advertising Agency Collection.

Jarvik-7 artificial heart, 1985. In August 1985 at the University Medical Center of the University of Arizona, Dr. Jack G. Copeland implanted this Jarvik-7 artificial heart in Michael Drummond, a patient awaiting a heart transplant. The Jarvik-7 kept Drummond alive until a donor organ became available one week later. Within months of the surgery, the medical center offered this artifact to the Smithsonian, which accepted it as a successful example of “spare parts”—devices or machines designed to function in place of a body part or organ—and an illustration of one of the controversies accompanying advanced medical technology. (photo credit 26.8)

Technology had other than business contexts; it also had a larger political story to tell. The last quarter of the twentieth century saw a recognition that technology had politics, that it did not proceed simply on its own technological logic. The National Museum of American History collected artifacts about immigration and the consumer movements, material protesting the nuclear arms race, and material documenting the environmental movement, macrobiotics, and alternative medicine.

Prototype for a LED (light emitting diode) electronic watch, about 1972. During the 1960s research teams from watch companies around the world raced to develop an electronic watch. This LED assembly was acquired in 1994 from John Bergey, a Hamilton Watch Company engineer. (photo credit 26.9)

Superconducting Super Collider electromagnet prototype on exhibit in Science in American Life, 1994. The SSC, which would have been the world’s largest particle accelerator, was cancelled because of costs. In this exhibition the prototype is shown with material from communities fighting both for and against the project. (photo credit 26.10)

In 1994 the National Museum of American History opened its first new exhibition on the history of science in many years. Science in American Life. The exhibition’s main label announced the curators’ intentions to portray science and technology as “right in the thick of American history,” an integral part of people’s daily lives, and a subject of political controversy and debate.

Not everyone was happy with the new exhibition. Scientists, used to their work being lauded as progress, as the driving force of positive social change, were upset to see science considered simply an aspect of culture. But by capturing science in its social and cultural context, Science in American Life in fact helped explain science in a way that an exhibition that isolated science never could. It helped visitors recognize science and technology as something shaped by people’s ideas, beliefs, and political agendas, not as an independent and impersonal force. It emphasized that society shapes and controls science and technology, not the other way around. And it encouraged visitors to understand progress, not simply celebrate it.74

Back in 1963 the Washington Evening Star introduced the Museum of History and Technology as “A Palace of Progress.” Today progress is still central to many of the stories the National Museum of American History tells, but science and technology are no longer isolated in a separate part of the palace. The palace now holds many kinds of stories, and more thoughtful, complex—and, yes, messy—understandings of science and technology are presented as components of the whole story of American history.

“Industrial Progress” poster, 1945. In the 1980s, as the National Museum of American History began to expand its collections beyond technology to include labor, it also began to collect artifacts representing business and management, including work incentive posters common in factories from World War I to the present. The museum had collected similar posters during World War II to illustrate industry’s contribution to the war effort and as graphic art. In the 1960s it acquired some ten thousand World War I and II posters from Princeton University Library. Posters like these portray corporate and government attitudes toward workers, technology, and industry. (photo credit 26.11)

DDT samples, 1940s and 1950s. Since the invention of DDT in 1939, the Smithsonian has acquired various samples of this controversial pesticide. Its collections include the first pound of DDT manufactured in the United States as well examples of farm and garden products containing DDT. (photo credit 26.12)

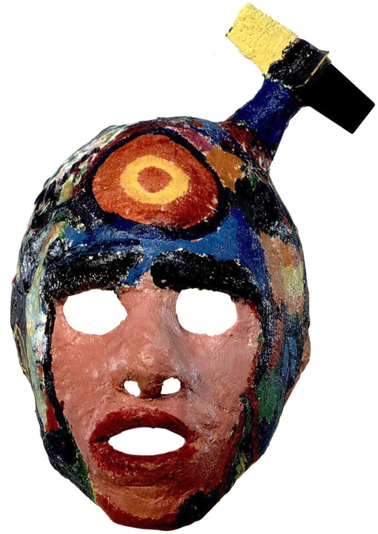

Nuclear arms protester’s mask, 1985. This mask was made and worn by sixteen-year-old Justin Martino for the Peace Ribbon March on the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., a 1985 demonstration for nuclear disarmament and world peace. Decorated with peace signs and a nuclear warhead that has missed its target. the mask symbolized Martino’s belief that “the arms race has no end except the end of life.” As a teenager concerned about the proliferation of nuclear weapons, Martino participated in several protests during the 1980s. After the Pentagon march, he and his father offered this mask to the Smithsonian to represent a young activist’s perspective. (photo credit 26.13)

“Ecology Now” poster, 1970s. By calling attention to pollution, destruction of wildlife habitats, and declining natural resources, the environmental movement has challenged conventional American ideas about science, technology, and progress. Curators collected this poster and other environmental materials for the Science in American Life exhibition in 1994. (photo credit 26.14)

Macrobiotic food, 1990s. In 1997 curators collected organic food samples from Michio Kushi, a founder of the American macrobiotic movement, as part of efforts to document alternative health and medical practices of the late twentieth century. (photo credit 26.15)