As the National Museum advertised the wonders of the modern age, it also commemorated the past that had supposedly made all this progress possible. In 1883, after receiving from the Patent Office extensive memorabilia of George Washington and other founders, the museum formally established a Section of Historical Relics. Expanding beyond its traditional focus on natural history, the National Museum was now also responsible for national history, charged with collecting new kinds of objects to honor key individuals and events and represent the cultural heritage of the American people.

Wooden mirror, probably 1700s. The letter that accompanied this mirror when it arrived at the Smithsonian in 1890 declared, “This looking glass came over in the May Flower.” Many other artifacts have come to the museum with similar stories connecting them to one of America’s founding families, but in this case curators have been unable to document the donor’s claims. Stylistic evidence—particularly the mirror’s shape, which is similar to that of so-called courting mirrors produced in northern Europe and imported to the colonies in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries—suggests the mirror may not have arrived in New England until more than a century after the Mayflower. (photo credit 28.1)

But the heritage represented at the National Museum at this time did not reflect that of all Americans, especially not the working-class people encouraged to come on Sundays. On the contrary, curators purposefully constructed a narrow view of the American past. The Hall of Period Costume, illustrating women’s fashions since colonial times, opened in the Arts and Industries Building in 1914 and soon became one of the most popular exhibits. Yet the costumes on display, curators were quick to point out, “do not include those of the lowly, but belong entirely to at least the well to do, and mainly to the wealthy and distinguished, the classes to which the term ‘fashion’ seems solely to appertain.” In addition to gowns, the hall also exhibited jewelry, combs, and “dainty lots of exquisite needlework and other family relics,” all of which, according to curators, demonstrated “the great taste with which our ancestors provided articles for their personal use.”5

At the National Museum, as in other museums at the turn of the twentieth century, American history was made available to all but truly belonged to only a few. Exclusive ownership of the national heritage was claimed by those who could trace their family roots back to the earliest days of the republic or, even better, the earliest days of English colonial settlement. Amid the influx of immigrants from countries outside western Europe, the impulse to draw ethnic, racial, and generational boundaries around American identity was strong among the native-born Anglo Americans.6

Silver shoe buckles, about 1779. These buckles, worn by Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Posey of the Seventh Virginia Regiment during the Revolutionary War, were donated to the Smithsonian by his granddaughter in 1921. In her letter to curators, she wrote that her grandfather “Danced at Stony Point in these buckles.” Stony Point, New York, was the site of a Continental Army victory in 1779. (photo credit 28.2)

To stake their claim on the American past, they donated family heirlooms to museums, formed preservation societies, and contributed funds to build monuments and save historic structures, ensuring that the individuals, events, and artifacts they valued would also be valued and remembered by the nation as a whole. The numerous heritage organizations that formed during this era, such as the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution (D.A.R) and the National Society of the Colonial Dames of America, defined their membership by colonial bloodlines. Members of these societies often donated heirlooms to the National Museum to pay tribute to their ancestors and demonstrate their patriotism. The D.A.R. and Colonial Dames also created historical collections of their own and occasionally staged special exhibits at the National Museum. Favored heirlooms ranged from jewelry, china, clothing (shoe buckles were especially popular), furniture, and needlework to military gear and church silver. The collection of Washburn family relics, donated by a Philadelphia woman in 1913, included a tile inscribed with the “Washbourne” coat of arms, salvaged from the ruins of an English abbey—tangible proof of the family’s Anglo-Saxon roots.7

In the National Museum’s historical exhibits, then, many visitors saw not themselves or their own ancestors but rather the ancestors of the white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant upper class—the people who, in the eyes of their descendants as well as museum curators, best represented America. In some cases curators themselves were descendants of these founding families. George Brown Goode, director of the National Museum from 1881 to 1896, was a scientist by training but also an amateur genealogist who was immensely proud of his Anglo-Saxon ancestry. Goode designed the logo for the Daughters of the American Revolution, which he based on his grandmother’s colonial spinning wheel; he also donated the heirloom itself to the D.A.R.

The Copp Collection, National Museum, about 1900. The collection of clothing, textiles, and household items used by the Copp family of Stonington, Connecticut, from about 1650 to 1850 is one of the museum’s largest family-based collections. Displayed at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago, the collection was later donated by John Brenton Copp to the National Museum, where it was exhibited to represent life in colonial times. (photo credit 28.3)

During his tenure as director, Goode eagerly solicited relics of historic American families for the National Museum. His most impressive acquisition was the Copp Collection, a large assortment of housewares, textiles, and furniture used by the Copp family of Stonington, Connecticut, from the mid-seventeenth to mid-nineteenth centuries. Like other members of the cultural elite, Goode believed that he was entrusted with a sacred responsibility to impart the true meaning of the American heritage to the public, to guard and celebrate his ancestors’ values and tastes as the core of a national culture. At Goode’s memorial service in 1896, William Lyne Wilson, U.S. postmaster general, eulogized him thus:

The study of the past, the study of the lives of those who have been eminent and useful men in the past, is a potent influence … [and an] intelligent, patriotic effort in the present. The noblesse oblige of a patriotic and substantial ancestry, not only for the individual but for the country itself, is a power whose influence we can scarcely exaggerate.8

Silver wine cup belonging to William Bradford, first governor of Plymouth Colony, 1634. Although the Smithsonian has widened its scope to include a diversity of American ancestors, the Pilgrim fascination persists. This cup remained in the Bradford family until the 1980s, when it came up at auction. Encouraged by S. Dillon Ripley, secretary of the Smithsonian and himself a Bradford descendant, curators moved to bid on the relic. Because of the cup’s rarity and expense, the National Museum of American History formed a partnership with the Pilgrim Society of Massachusetts to purchase it in 1985. The museums now share ownership of the cup and take turns displaying it. (photo credit 28.4)

When the National Museum first began collecting from founding families in the 1880s and 1890s, artifacts were valued mainly for their historical associations. If they happened to be visually attractive too, so much the better. But even tarnished shoe buckles or a glassless wooden mirror, as long as it was connected to an old and prominent American family, was generally accorded as much respect as jewelry and silver. By the early twentieth century, however, curators and collectors alike were looking for something more from the past: style. As the United States began to claim its place on the world stage through war and diplomacy, nationalist feelings compelled many to search for evidence of a unique American culture, distinct from European cultures. As contemporary artists cultivated styles that were self-consciously American, they looked to early American artifacts for inspiration. What was it in the design of a Paul Revere teapot or a Philadelphia tea table that reflected American tastes, values, and traditions?

Gunboat Philadelphia, 1776. The Philadelphia was one of a fleet of Continental gunboats that stopped the advance of British forces on Lake Champlain during the Battle of Valcour Island in 1776. Sunk during the battle, it was discovered and raised in 1935 by Lorenzo F. Hagglund, a civil engineer who for many years exhibited it as a tourist attraction. In 1939 a Smithsonian curator proposed buying the Philadelphia, citing a naval historian who called it “the most amazing thing of the sort that he has seen.” But the idea was rejected by museum officials, who balked at the price and thought the gunboat better off in its “original surroundings.” Twenty years later the curator, Frank Taylor, had become the director of the new Museum of History and Technology, and he still wanted the Revolutionary War relic for the collections. In 1961 the Smithsonian acquired the gunboat and brought it to Washington, D.C., where it was displayed along with other naval artifacts salvaged from the lake bottom. In 1991 detailed drawings of the gunboat were used to make a replica, the Philadelphia II. (photo credit 28.5)

Meanwhile, many Americans not only wanted to preserve their colonial heritage; they also wanted to furnish their homes with it. Antique collecting became a passion among the upper and middle classes alike, and for those who could not afford the real thing or find antiques that matched their décor, furniture factories began reviving colonial styles for their new product lines. Museums presented colonial objects as decorative arts, emphasizing their beautiful design and craftsmanship over their purely historic value, and used them to define an “American” style—as opposed to the styles of immigrant cultures—that the public was encouraged to appreciate and emulate. Thus, in 1914 the National Museum’s Hall of Period Costume offered not just relics of founding families but also evidence that the nation’s founders had “great taste.”9

A new type of museum exhibit, the period room, evolved to meet the demand for artistic antiques and provided an opportunity for Americans with colonial pedigrees to showcase their inheritance. Pioneered in 1907 at the Essex Institute in Salem, Massachusetts, the nation’s oldest historical society, the period room made its biggest public splash in November 1924 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Mew York. The Metropolitan’s new American Wing exhibited a lavish array of decorative arts and furnishings within “authentic” room settings, constructed from the salvaged architectural details of historic houses; many of the period rooms and their contents had been donated by wealthy patrons as a tribute to their own patriotism and good taste.10 Here American history was framed as art, and the value of artifacts derived from their aesthetic rather than associational qualities.

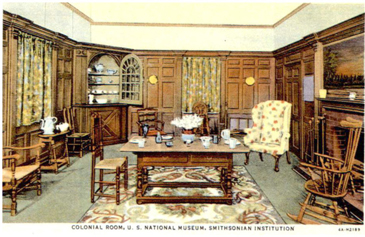

That same year another wealthy antique lover selected the National Museum as the repository for her tasteful legacy. Gertrude D. Hitter presented curators with the pine paneling from the parlor of a mid-eighteenth-century Springfield, Massachusetts, house she had purchased in 1923, along with a collection of colonial artifacts to furnish the room. It was the first period room acquired by the museum, and curators were quite excited to receive it. Ritter intended the room as the first step in her grand plan to assemble a “complete Early American House” at the National Museum. After the colonial parlor was installed, Ritter herself took an active role in managing the exhibit. As a condition of her gift, she reserved “the right to replace any articles of furniture or furnishing in said room with other similar articles which may seem to me to improve the quality of the collection for museum purposes.” She selected objects for the room from an extensive antique collection stored at her Vermont home, Yester House. In 1930 Ritter visited the National Museum and was very upset with the condition of “her” room; she spent four hours cleaning the furnishings and demanded that a wood expert be brought in to repair the deteriorating paneling. By the 1930s officials were balking at Ritter’s original plan for a complete house to be erected in the museum, citing cost and space concerns. Disappointed, Ritter changed her will and left her Yester House collection to her alma mater, the University of Michigan.11

By the 1920s some Americans were openly challenging the founding families’ exclusive claim on the nation’s heritage. They criticized the worship of Puritan ancestors and the textbooks that granted New England a privileged place in national history while downplaying the contributions of other regions.12 With the onset of the Great Depression, the elite literally lost their grip on the past as many once-wealthy collectors were forced to sell off their antiques; as prices dropped, more Americans could afford their own piece of history.13

The Colonial Room as exhibited in the Natural History Building in the 1930s, in the Museum of History and Technology in the 1970s, and in the National Museum of American History in the 1980s (above, opposite top, and opposite bottom). Since it was acquired in 1924, this pine-paneled room has been exhibited in a variety of contexts, reflecting changing interpretations of American history and new historical evidence. The room was originally believed to be the parlor from the house of Reuben Bliss, a joiner who lived in Springfield, Massachusetts. In 1981 Edward F. Zimmer, an architectural historian, discovered that the room did not match the dimensions and design of the Bliss house. He speculated that the room came instead from the house of the merchant Samuel Colton, constructed in Long-meadow, Massachusetts, in the 1750s and demolished in 1916. These findings shaped the new display of the room in the 1985 exhibition After the Revolution. (photo credit 28.8)

In this and many other ways throughout the 1930s, history was gradually becoming more accessible to and reflective of the people. Automobiles brought museums and historic sites within reach of more Americans, and more sprouted up to serve the tourists who rolled into town on the new highways. Meanwhile, as the federal government expanded to contend with the nation’s economic crisis, it also assumed an unprecedented responsibility for the nation’s history. In 1934 the National Archives was created to house and preserve government records and historic documents of national significance, including the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. The National Park Service, established in 1916 to protect the country’s natural treasures, now turned its attention to cultural treasures as well by acquiring, surveying, and preserving historic sites and buildings. Through New Deal work-relief agencies such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the government hired writers and photographers to document the histories of people not ordinarily showcased in museums, such as former slaves and migrant workers. For the Index of American Design, part of the WPA’s federal art project, artists produced detailed watercolor images of thousands of antique arts and crafts—not famous objects associated with founding families but the creations of largely anonymous artisans and folk artists whose work represented the varied craft traditions of the United States.14

The Smithsonian lent its support to many of the federal government’s historic preservation programs during the 1930s. With the WPA, it codirected the Historic American Merchant Marine Survey, whereby numerous models, plans, photographs, and drawings of historic watercraft were produced and deposited in the National Museum collections. The museum also hosted WPA exhibits, featuring the Index of American Design and state guidebooks produced by the Federal Writers’ Project. Yet within its own historical collections, little evidence of this movement toward a more democratic, inclusive view of the American past could be detected. National history at the National Museum still consisted mainly of political relics and antiquarian treasures. After World War II, however, things began to change, slowly but surely, and the changes started in Gertrude Ritter’s period room.