In 1968, when Secretary Ripley urged curators to “tell it like it is,” he wanted the Smithsonian to include the traditions and contributions of diverse ethnic and racial groups. Since then the Smithsonian has collected many artifacts to construct a multicultural image of America, one that celebrates diversity as an enduring and defining characteristic of national life. Regarded together and from a distance, these objects suggest a variegated tapestry, a common national fabric woven of many colorful strands. And in 1976, a year intended to symbolize the reuniting of a country fractured by a decade of conflict and dissent, such pluralistic unity was the overwhelming message of A Nation of Nations. Yet objects are more than just emblems of diversity; they offer more than just stylistic evidence of ethnic origins. They are connected to people’s lives, to their experiences, values, and beliefs. And when history is examined from the point of view of the people who made and used these artifacts, to include not only their faces but also their own voices and stories, American history—and America itself—begins to look very different. New kinds of stories emerge—stories not of national unity and prosperity but of conflict and inequality, of injustice and discrimination, of a nation that did not always live up to its promises.

Button from March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, 1963. One of the first artifacts of the civil rights movement collected by the Smithsonian, this button was brought in by an employee who participated in the march. (photo credit 32.1)

On August 28, 1963, more than a quarter of a million Americans, black and white, came together in Washington, D.C., to march for racial equality. They gathered at the Lincoln Memorial and listened to a speech by the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., which would forever echo through the nation’s conscience. King described his dream of what America should be, contrasting that vision with the current reality of a nation plagued by racism, poverty, and inequality, a nation where blacks and whites inhabited separate and unequal worlds, where children of different races were educated in separate and unequal schools, where black workers were kept out of better jobs and paid unequal wages. They listened as he urged all Americans to close the gap between dream and reality, to hold the nation to its highest ideals.

While his “I Have a Dream” speech focused on the future, the backdrop for King’s message, the giant marble statue of Abraham Lincoln, symbolically cast the civil rights movement as a historic struggle and the March on Washington as a historic moment. The march was one more step in a long series of steps toward racial equality; the journey was not yet complete, but by participating the marchers claimed their place in line, their place in history. Indeed, many wore this sense of historic importance on their sleeves in literal form: metal buttons emblazoned with the date of the march.

Anti-Vietnam War poster by Sarah Beach, 1970s. When Beach, an artist and activist, visited the National Museum of American History in 1976 to see We the People, an exhibition on American politics, she was surprised to find herself part of the show. A Smithsonian photographer had snapped her picture at an antiwar rally, and curators had turned the image into a life-size figure for a display about political protest. Although pleased to be included in the exhibition, Beach did not agree with the slogan on the sign attached to her mannequin. Curators agreed to change the sign, and in 1977 they also collected two posters Beach had made and used in antiwar demonstrations, including this newsprint collage. (photo credit 32.2)

One woman who participated, a Smithsonian employee, believed so strongly she had helped make history that she brought her buttons into work and presented them to a curator, hoping the meaning and message of that day would be preserved in the museum’s historical collections. But the message of these buttons was far different from the message presented by the Smithsonian in 1963. The new Museum of History and Technology, then under construction on the National Mall, promised to be a place where visitors to the nation’s capital would find “a stimulating permanent exposition that commemorates our heritage of freedom and highlights the basic elements of our way of life.”45 Yet as civil rights activists pointed out, the nation’s heritage also included the struggle of African Americans and other groups for the freedom that had been granted to others but denied to them. Would this story also have a place in the museum of American history? Did it belong there?

Traditionally, as shown here, the answer had been no. The Smithsonian did not tell those kinds of stories. In the aftermath of the Civil War, amid the influx of immigrants at the turn of the century, and during the patriotic fervor of the two world wars, many Americans had looked to history as an escape from present-day problems and a way to promote patriotism and national unity. And the Smithsonian had responded by furnishing a celebratory, homogeneous, and conflict-free view of the American past. Now, at the height of the Cold War, many Americans wanted a national history museum that would encourage consensus at home and project a unified and prosperous national image abroad. As long as consensus remained the museum’s goal, its view of American history would have to exclude certain groups—African Americans, Native Americans, immigrants, the working class—whose experiences raised troubling issues of social inequalities and cultural differences.

Equal Rights Amendment charm bracelet, 1972–74. Alice Paul, a feminist who spent her life campaigning for women’s rights, originally proposed the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) in 1923 as the leader of the National Woman’s Party. In 1972 the ERA was reintroduced, and Paul, now in her eighties, again actively campaigned for its passage and ratification. The charms on her bracelet represent states that ratified the amendment; however, not enough states did so, and the ERA never became law. In 1987 the Alice Paul Centennial Foundation donated a large collection of memorabilia, including this bracelet, to honor the 100th anniversary of her birth. (photo credit 32.3)

But by the 1960s these troubling issues were becoming increasingly visible and difficult to ignore. Television broadcast into American living rooms jarring images of protest and violence, of civil rights demonstrators being attacked by dogs and sprayed with fire hoses; of assassinations, strikes, and riots; of the war in Vietnam and the war over Vietnam. Everywhere Americans looked there seemed to be chaos, discord, rebellion. And when they came to the Smithsonian and saw visions of a prosperous, harmonious national past, a people sharing common values and traditions, many wondered what was happening to their country, what had gone wrong.

Antislavery medallion, about 1787. This jasperware cameo, made at Josiah Wedgwood’s factory in Staffordshire, England, features the motto adopted by the British Committee to Abolish the Slave Trade in 1787: “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” An active abolitionist, Wedgwood sent one of these cameos to Benjamin Franklin in 1788, hoping to promote American support for the antislavery cause. This medallion originally came to the Smithsonian in 1968 as part of a large loan from Lloyd Hawes, a prominent collector of English ceramics. The medallion was featured in a major exhibition, After the Revolution, and in 1987 the loan was converted to a gift. (photo credit 32.4)

Confronted with this disparity, a handful of curators in the late 1960s decided that the answer was not to retreat further from conflict and protest but to embrace it. In 1968, as the Poor People’s Campaign set up tents on the National Mall, Keith Melder, a curator in the political history division—which up to this point had consisted mostly of presidential relics, first ladies’ gowns, and campaign memorabilia—ventured out and collected banners, placards, even a plywood shelter painted with slogans. From then on, whenever civil rights and antiwar protesters flooded the streets of Washington, curators often followed, picking up flags, posters, and other mementos of the demonstrations. And as the women’s liberation movement got under way in the early 1970s, Edith Mayo, curator, attended rallies and political caucuses to collect material. It was the first serious attempt to document contemporary women’s issues since 1920, when the National American Woman Suffrage Association had donated relics of Susan B. Anthony to commemorate the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment.

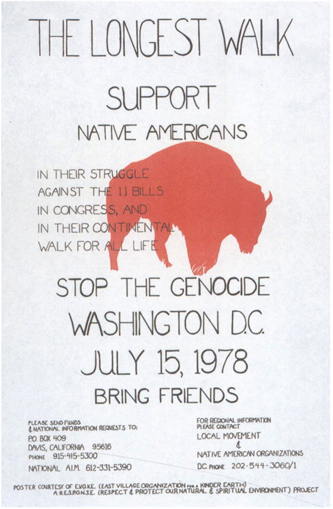

“Longest Walk” poster, 1978. In the 1970s, as Native Americans mobilized to demand tribal rights, protest treaty violations, and call attention to economic devastation on the reservations, the Smithsonian documented their activities by collecting buttons, pamphlets, posters, T-shirts, and other material. This poster from the Longest Walk, a pan-Indian civil rights march from California to Washington, D.C., was acquired from the march’s Washington headquarters in 1978. (photo credit 32.5)

Curators did more than simply document what was going on outside the museum’s front door; they also began to seek out artifacts that spoke to the presence of similar conflicts in the nation’s past. Contrary to what the conventional picture of American history suggested, political protest was not a modern invention. Racism, poverty, and inequality were not just current problems; they had roots stretching back to the earliest days of the republic and beyond. In the 1960s and 1970s a new crop of historians, many of them women and minorities, started to probe the depths of racial, ethnic, class, and gender divisions in American society, to make connections between past and present struggles. Their discoveries in turn shaped the museum’s work, giving rise to new ideas about what was worth saving from the nation’s past and what stories were important to tell.

In 1980 the Museum of History and Technology was officially renamed the National Museum of American History. In the decade that followed, the museum opened a series of new exhibitions focusing on the historical experiences of women and minorities. Field to Factory, curated by Spencer Crew—one of the museum’s first African American curators and in 1994 its first African American director—opened in 1987 and told the story of the migration of African Americans from the rural South to the industrial North during the first decades of the twentieth century. Among the featured artifacts were a sharecropper’s cabin, a Ku Klux Klan robe, and a set of doors marked “White” and “Colored,” symbols of the racism and segregation African Americans confronted in their daily lives. The same year the museum unveiled A More Perfect Union, an exhibition about the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. Sponsored by Congress to commemorate the bicentennial of the U.S. Constitution, the exhibition focused on a time when constitutional guarantees were denied to some Americans because of their ethnic ancestry. Curators collected numerous artifacts for the exhibition from former internees and their descendants in collaboration with the Japanese American Historical Society. A third exhibition, From Parlor to Politics, which opened in 1990, traced women’s involvement in the reform and suffrage movements of the Progressive Era. It featured artifacts acquired for the women’s history collection, ranging from a wagon painted with suffragist slogans to a tiny pin commemorating the jailing of suffragists who picketed the White House in 1917 as well as artifacts documenting women’s work in settlement houses, education, labor reform, nursing, and the antiwar movement.

“Acid Test” signboard, about 1964. The adventures of the Merry Pranksters—a band of artists, writers, and students who embraced free expression, defined a lifestyle opposed to mainstream American values, and traveled the country in a psychedelic schoolbus—were popularized in Tom Wolfe’s 1968 book The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Led by the novelist Ken Kesey, the group became a symbol for the counterculture based in San Francisco during the 1960s. In the early 1990s Smithsonian curators contacted Kesey hoping to acquire the famous bus, named Furthur, but it was badly deteriorated. In 1992 they collected archival material and this colorful plywood panel, which the Pranksters used to advertise concerts and poetry readings. Fittingly, Kesey signed the deed of gift with a Day-Glo marker. (photo credit 32.6)

These new exhibitions aimed to tell the story of America from a new point of view, to give new perspectives on familiar events, and to raise awareness of social inequalities, past and present. This effort continued with the 1992 exhibition American Encounters, which took as its inspiration the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in the New World and explored the centuries of encounters between Native Americans, Hispanics, and Europeans that shaped the history of modern-day New Mexico. The curators undertook extensive field research, conducting oral history interviews and collecting both contemporary and historical artifacts. Through these artifacts the exhibition challenged traditional interpretations of encounters between Indians and Europeans; for example, the exhibition described not only the conversion of Native Americans to Catholicism but also the adaptation of Catholicism to accommodate Indian customs and beliefs—what curators described as the “Indianizing” of Christianity.46 Many objects collected for American Encounters, such as a beaded doll depicting a white tourist made by a Zuni Pueblo artist, symbolize the Native American point of view that has traditionally been excluded from collections and exhibitions.

Jar made by David Drake, a slave artisan, 1862. The poem inscribed on this glazed stoneware reads “I made this jar all of cross/If you don’t repent, you will be lost” and is signed “Dave.” David Drake worked at the pottery operated by his owner, Lewis Miles, at Stoney Bluff Plantation in Edgefield, South Carolina, from the 1830s to the 1860s. He is the only slave potter known to sign and date his work, defiantly proclaiming his education in a state that outlawed literacy among slaves. In 1996 the Smithsonian purchased two of Dave’s “poem jars,” highly valued as artistic works and material evidence of the skills, beliefs, and daily lives of enslaved African Americans. (photo credit 32.7)

Barracks sign from Manzanar relocation center, California, 1942–45. During World War II thousands of Japanese immigrants and Japanese American citizens were evacuated from their homes on the West Coast and relocated to internment camps because the U.S. government considered them a threat to national security. This wooden sign identified the residence of Michibiku Ozamoto in the Manzanar camp; the numbers stand for block 24, barracks 4, apartment 3. The Smithsonian collected this sign and other artifacts from former internees and their families for its 1987 exhibition A More Perfect Union. In 1988 Congress formally apologized to Japanese Americans and granted cash reparations to surviving internees. (photo credit 32.8)

“Jailed for Freedom” pin, 1917. Between 1917 and 1919 suffragists, demanding votes for women, picketed the White House, and many were arrested and jailed. The women later wore pins representing a prison cell door to commemorate their imprisonment and call attention to the injustice of being “jailed for freedom.” The National Museum of American History has collected several of these pins. The first was donated in 1963 by Lucille Agniel Calmes, a government secretary who served a five-day term in the District of Columbia workhouse for picketing in 1919. This pin belonged to Alice Paul of the National Woman’s Party, who led the first picket in 1917; it was acquired in 1987 from the Alice Paul Centennial Foundation. (photo credit 32.9)

Another point of view the museum has worked to address in recent years is that of workers, the people who made and used the machines and tools that have long been part of the technology collections. In 1989 these efforts were given a tremendous push forward by Scott Molloy, a labor activist and historian at the University of Rhode Island, who offered to the museum his vast collection of artifacts documenting the history of organized labor. In arguing for the acceptance of the Molloy Collection, curators noted that “the inclusion of labor materials, and the inclusion of working-class history, in our collection is vital if we are to fulfill our responsibility as a museum for all the American people.”47 Since then, the museum has continued to add to its labor history collection, particularly artifacts that represent crucial intersections of race, ethnicity, class, and gender issues.

In 1998 a groundbreaking exhibition exploring these issues opened at the museum. Between a Rock and a Hard Place: A History of American Sweatshops originated when curators, already planning an exhibition on low-paid labor, learned of a police raid on a sweatshop on El Monte, California, in 1995 and decided to collect artifacts documenting the incident. In the exhibition Peter Liebhold and Harry Rubenstein, curators, used the El Monte raid as an opportunity to trace the history of sweatshops in America and raise questions about why these illegal and abusive labor practices have persisted despite extensive reform efforts. In addition to relating the historic stories of immigrants, mostly women, who have worked in sweatshops, the exhibition also included the contemporary voices of El Monte workers, local authorities, manufacturers, and labor unions.48

Since A Nation of Nations, the National Museum of American History has approached history not only from the bottom up but also from the outside in. It has collected artifacts that show America from the perspectives of individuals and communities who were not always included or accepted by society at large. From a carved sun stone that was part of the first Mormon Temple to a panel from the AIDS Memorial Quilt, these objects preserve experiences and beliefs that were at one time regarded as outside the mainstream. Some groups fought for social acceptance; others, like the 1960s counterculture group the Merry Pranksters, preferred to drop out and create their own society. Yet they all defended their right to be themselves, to be Americans on their own terms. In the process of defining their place in the nation, they challenged, adapted, and redefined ideas about what place the nation occupies in people’s lives.

Re-creation of El Monte sweatshop, National Museum of American History, 1998. On August 2, 1995, authorities raided a sweatshop in El Monte, California. Inside the fenced-in compound they found seventy illegal Thai immigrants who had been forced to work sixteen hours a day, seven days a week, sewing garments that would eventually be sold in major chain stores around the country. Smithsonian curators saw the incident as “an iconic event in American work history” and collected material from former workers and agencies involved in the raid. (photo credit 32.10)

Mormon sun stone, 1844. Drawn from a dream vision of Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism, sun stones and other celestial carvings adorned the Mormon Temple built at Nauvoo, Illinois, in 1844. But the elaborate temple was destroyed soon after by people opposed to Mormons and their religious beliefs. To escape further persecution, the Mormon community moved west and settled in Utah. This sun stone, salvaged from the ruined Nauvoo temple and preserved by a local historical society since 1913, was offered to the Smithsonian in 1989. To Richard Ahlborn, the Smithsonian’s religious history curator, it represented a chance to explore “the complexity of our nation’s spiritual origins.” (photo credit 32.11)

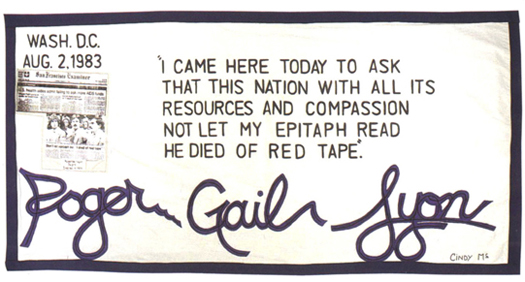

Panel from the AIDS Memorial Quilt, 1987. This panel, one of more than forty thousand made since 1987 to memorialize people who have died of AIDS, is dedicated to Roger Lyon, an AIDS activist who testified before Congress in 1983. A new interpretation of a traditional American craft, the quilt aims to change Americans’ view of the AIDS epidemic—not as a moral or lifestyle issue but as a global health crisis. This panel was sent to the Smithsonian in 1990 by The NAMES Project, which maintains and displays the quilt. At the time many considered AIDS too politically sensitive a topic for the Smithsonian to address. However, as the quilt was displayed several times on the National Mall and grew ever bigger, public concern also increased. In 1998 the panel became a permanent part of the museum’s medical sciences collection, which in recent years has tried to document not just medical technology but also the political, social, and cultural aspects of health and medicine. (photo credit 32.12)