Of course, once objects enter a museum, they are not in the real world anymore. Removed from their natural habitat, so to speak, preserved in drawers or placed on pedestals under spotlights, objects are no longer held to the same rules. They become artifacts, specimens to be catalogued and classified. They are no longer useful, at least not as they once were. A hammer in a museum is no longer used to drive nails. A bed is no longer slept in. Shoes are no longer worn or clicked together three times. Their story of use comes to an end. In Eccentric Spaces (1977), the architecture critic Robert Harbison writes, “The result museums seek is an end to change, a perfect stasis or stillness; they are the final buildings on the earth.… In order to enter, an object must die.”9

An object may have to die to enter a museum, but—to continue Harbison’s metaphor—when it dies and becomes part of the collection, it begins an afterlife. One is tempted to say it dies and goes to heaven. From a conservation standpoint this is certainly true. With its specially tailored environmental conditions and attentive physical care, a museum must seem like heaven to an artifact. But in fact it is more purgatory than heaven, for in this afterlife artifacts find a new life—not in use or activity but in meaning. The value of a museum artifact is measured not by how well it does what it was originally made to do or how much money it is worth to a collector but by the stories it can help tell about the American past.

One type of story centers around the object’s own history. When was it made? What is it made of? Who made it? How was it used? These kinds of questions establish basic information about the object; they help identify and locate it in time and place. A related issue is that of provenance: Who owned the object? Whose hands did it pass through between the day it was made and the day it came into a museum? Provenance is very important for curators and collectors alike, both of whom are concerned with verifying the authenticity of artifacts. Technological marvels of virtual exhibits aside, visitors still come to museums expecting to see the real thing; the powerful appeal of actual pieces of history, of encountering the past in person, draws millions of tourists to the Smithsonian and other museums and historic sites every year.10

Silver peace medal, 1801. The practice of giving medals to Native American tribes to promote diplomatic relations began during the early colonial era and continued up to the late nineteenth century. Presented by explorers, military officers, and government officials, the U.S. medals bore the likeness of the current president and various symbols of peace and friendship. To the chiefs and delegates who received them, the medals were prized possessions, badges of power and status that were often buried with them. This silver peace medal, issued under President Thomas Jefferson, was given to an Osage chieftain and passed down to Chief Henry Lookout, the last hereditary chief of the Oklahoma Osage tribe. In 1952 Lookout loaned the medal to the Smithsonian, and in 1990 his heirs allowed it to become a permanent part of the numismatics collection at the National Museum of American History. Of the many peace medals in the museum’s collection, this is the only one known to have been presented to a Native American. (photo credit 35.1)

While it is possible in some cases to document a chain of ownership dating to the object’s original owner, more often than not curators must rely on their own knowledge and judgment to determine whether an object is authentic. But in a museum, authenticity is itself a tricky concept. Does restoring an object to its original appearance—patching up holes, removing extra layers of paint, scrubbing off the patina—make it more authentic or less authentic? If the object is missing a piece, should the piece be reproduced or left missing? Which object—the restored, polished, and complete one or the decayed and tarnished one—provides a more accurate picture of life in the past? Curators continue to wrestle with these questions as they try to balance the demands of historical accuracy with visitor expectations of an authentic museum experience.

Examining an object under a microscope—literally or figuratively—can reveal many fascinating facts about the object’s own history. But when museumgoers start to imagine the artifact not in a spotlight by itself but against a variegated backdrop of people, places, and events, many more interesting stories emerge. They begin to understand the role an object played in people’s lives, the meanings it held to different individuals and communities, the way it reflected the knowledge, values, and tastes of a particular era. In short, they see the object as part of American history.

When placed in context, artifacts become passageways into history. Through a single object, viewers can connect to a moment in time, a person’s life, a set of values and beliefs. To take advantage of the opportunities artifacts offer, one must first be aware of their nature: how they function in people’s lives and how they become invested with meaning. Consider these four statements: Artifacts connect people. Artifacts capture moments. Artifacts reflect changes. Artifacts mean many things. These are simple phrases, but they suggest the enormously complex relationships that exist between people, artifacts, and history. By keeping these ideas in mind when looking at an artifact—whether found in a museum case, an attic trunk, or a store window—viewers open themselves up to new meanings, new stories, and new perspectives on the past. They discover new reasons why artifacts are worth saving.

Phrenology model, 1860s. For much of the nineteenth century, Americans looked to the pseudo-science of phrenology to decipher the mysteries of human behavior and personality. As this model illustrates, phrenologists believed the brain was divided into thirty-seven distinct physical organs, each responsible for a different trait such as acquisitiveness, benevolence, or spirituality. By “reading” the bumps on a person’s head, a phrenologist could determine which characteristics were most prominent. While emphasizing the link between biology and behavior, phrenology also held that, through intellectual and moral exercise, individuals could alter the size and shape of their brain and thus improve their character. This bust, created by Lorenzo Niles Fowler, a leading manufacturer of phrenological paraphernalia, was purchased in 1961 for the medical history exhibition in the new Museum of History and Technology. (photo credit 35.2)

The life of an object and the way it came to be in a museum is a story of provenance. Its afterlife, though, is a story of possibility. In the real world an object’s meaning is fixed to a particular time and place. But once the object enters a museum, it can be inserted into a variety of stories, examined from diverse points of view—it can become, in essence, many different objects. “By emphasizing the narrative possibilities of artifacts rather than their specific provenance,” write Spencer Crew, director of the National Museum of American History, and James Sims, exhibit designer, “exhibitions can encourage visitors to think more broadly about things and their meanings. They can help to demystify objects.… Artifacts so framed make an immediate claim on the visitor’s time and can turn a museum visit into an encounter with past lives.”11 In a museum, artifacts move beyond provenance to possibility. There are opportunities for new interpretations, new contexts, new stories. An object can transcend its own history; it can become a symbol of common experiences or cultural beliefs, or it can become an icon of an era or event; it can highlight important themes in history or personify an individual, a community, even a nation. The artifact sitting in a museum storage cabinet is not dead; it is a story waiting to be revealed.12

Silver teapot, 1752. Artifacts connect people. As artifacts are made, used, and passed on, they create a web of relationships. This silver teapot, centerpiece of the social ritual of taking tea, also linked family members across generations. It was made by the silversmith Samuel Casey, assisted by his apprentices, for Abigail Robinson, the daughter of a wealthy Rhode Island planter, on her marriage in 1752. Seventeen months later Abigail died, childless, at age twenty-two. Her husband remarried and had a daughter, Mary Wanton, to whom he gave the teapot as a wedding gift in 1782. The teapot was passed down in the family until 1979, when the Smithsonian purchased it at auction. (photo credit 35.3)

Kodak Brownie camera, about 1910. Artifacts capture moments. They preserve memories and embody the tastes, lifestyles, and technical knowledge of their times. On April 15, 1912, seventeen-year-old Bernice Palmer, a passenger aboard the Carpathia, used this camera to document the ship’s rescue of survivors of the Titanic. In 1986, when she donated her camera and photographs to the National Museum of American History, she recalled the tragic moments she had captured on film: “After all the survivors were safe on board our ship, the Carpathia, it sailed all around the area where the Titanic struck and sank. It was then when I saw the floating deck chairs … did I realize the terrible disaster which had happened.… There is much more which I will never forget.” (photo credit 35.4)

Remington typewriter, about 1875. Artifacts reflect changes. They provide opportunities to compare past and present, to consider how and why change occurs. At the time it was produced, this typewriter, manufactured by E. Remington and Sons about 1875, reflected changes in the workplace that accompanied the rapid growth of corporations during the late nineteenth century. By opening up white-collar employment for women, the typewriter also became an agent of social change. In 1912, when the Remington Typewriter Company donated this one to the Smithsonian, it illustrated progress. Described as “one of the very first models of the writing machine ever manufactured,” it suggested how far technology and design had advanced since the 1870s. (photo credit 35.5)

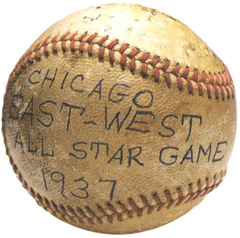

Negro Leagues baseball, 1937. Artifacts mean many things. More than just material things, they communicate ideas, symbolize values, and convey emotions. Consider the changing meanings invested in this baseball from the Negro Leagues East-West all-star game of 1937 Buck Leonard, first baseman for the Homestead Grays, hit a home run to help the East win, 7–2, and kept this baseball as a souvenir of the game. In 1947, when racial integration of major-league baseball effectively ended the need for the Negro Leagues, this baseball became a piece of history. In 1972 the ball became a collector’s item when Leonard was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Leonard saved this ball for nearly forty-five years before finally donating it to the Smithsonian in 1981. (photo credit 35.6)