A Palace of Progress

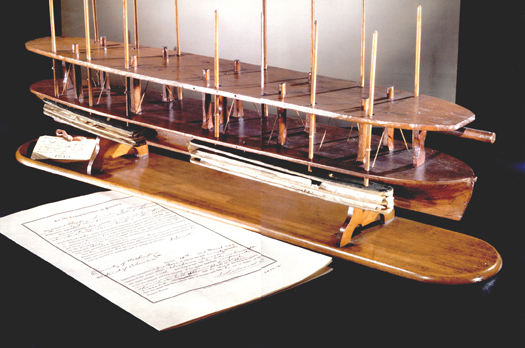

Patent model and application submitted by Abraham Lincoln, “Method of Buoying Vessels over Shoals,” 1849. The only American president to receive a patent, Lincoln came up with this idea in 1848, a result of being stranded on sandbars during his boat travels. Although his device was never manufactured, Lincoln held a life-long interest in technology and the inventive process. The Smithsonian acquired this model from the Patent Office in 1908. (photo credit p04.1)

Since its founding, the Smithsonian has reflected and promoted a gospel of progress. Its collections and exhibits have celebrated the material advances of modern society and honored the scientists and inventors who made these advances possible. Yet the Smithsonian has also long been a place where the nature of invention, innovation, and technological change has been debated.

IN MAY 1963 THE WASHINGTON EVENING STAR PULLED OUT ALL the stops for a full-page article on the newest Smithsonian building under construction on the National Mall: the Museum of History and Technology, Hailing the wonders of this “Museum with Widest Scope,” the headlines announced that the “Big Marble ‘Shrine’ Is Coming Alive with First Exhibits,” including the “Latest in Electronics,” Splashed over the whole page, in the biggest type, was the bold proclamation: “New Smithsonian Unit to Be a Palace of Progress.”1

At the helm of this monumental enterprise was the museum’s director, Frank Taylor, described by the reporter as “a gentle, soft-spoken and modest man.” Asked to comment on the significance of this “shrine of American pioneering and progress,” Taylor replied that the new Smithsonian museum was a unique creation, “for under one roof it combines the history and technology of a Nation. In a country such as ours, we think these are inseparable because of the tremendous influence science has had on our way of living and our development.”

The excitement surrounding the construction of the Museum of History and Technology invoked American attitudes toward science and technology that date back to at least the early nineteenth century. As a young nation founded on new ideas, the United States developed a national identity oriented toward the future, toward establishing, as the Constitution phrased it, “a more perfect Union.” This willingness to experiment, to break with tradition and create new solutions to old problems, combined with an intense regard for individual freedoms, created a climate favorable to scientific and technological innovation, America gained a reputation as a land of invention, the home of Yankee ingenuity. Meanwhile, as industrial growth and new inventions began to revolutionize how Americans lived, worked, and played, many linked material progress to social progress, believing that advances in science and technology would in turn foster improvements in society.

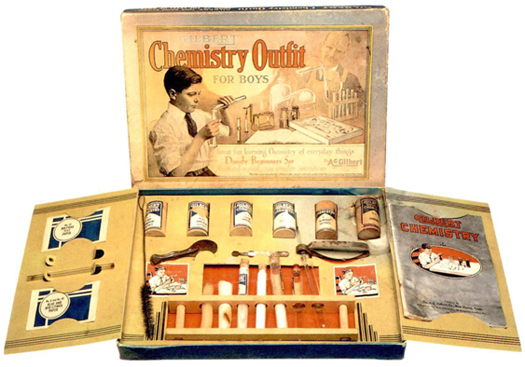

Gilbert Chemistry Outfit for Boys, 1936. Children’s toys often reflect widely held beliefs more clearly than the adult models on which they are based. The National Museum of American History’s many science and technology toys, such as this chemistry set, collected in 1992, capture the essence of American beliefs about Yankee ingenuity. (photo credit p04.2)

Since its founding in 1846, the Smithsonian Institution has reflected and promoted this gospel of progress. Its collections and exhibits have celebrated the material advances of modern society and honored the scientists and inventors who made these advances possible. The museum has been a place to see how things improve over time, to compare the “primitive” devices of ancient days to the sleek, efficient modern designs of today. And, especially since the early twentieth century, it has been a place where American innovations and innovators take center stage, where progress is displayed to inspire patriotism and national pride.

Yet as a place dedicated to research in anthropology, the history of science and technology, and social and cultural history, the Smithsonian has also long been a place where the nature of invention, innovation, and technological change has been debated. In bringing artifacts into the collections and deciding how to display them, curators—among them scientists, anthropologists, engineers, and historians—have thought long and hard about the complex relationship of science and technology to people’s lives and to American history. Their beliefs, scholarly research, and professional interests have shaped how the Smithsonian has collected and exhibited science and technology. In the 1880s scientists and anthropologists set the terms of the debate. By the early twentieth century, engineers made many of the decisions. In more recent years historians have had a larger say.

Spinning frame from Slater Mill, Pawtucket, Rhode Island, 1790. This spinning frame, designed by Samuel Slater using an English model, was installed in Slater’s Pawtucket mill, the first successful industrial mechanized textile mill in America. Preserved by the Rhode Island Society for the Encouragement of Domestic Industry, it was donated to the Smithsonian in 1883. “This relic,” read the accompanying letter, “is most valuable—the first spinning frame ever started in America (1790)—the rude beginning of all that vast New England industry—cotton spinning and weaving.” Although the society hesitated to let the spinning frame leave the state, it believed that the Smithsonian was the place “where the citizens of our Common Country may view it and learn of its history. No place offers a superior claim to your Department for the preservation of this valuable historical relic.” (photo credit p04.3)

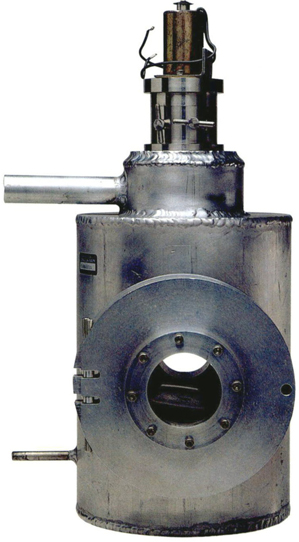

Gene gun, 1987. Devised by John Sanford at Cornell University, the gene gun made it easier to introduce new genetic material into a cell. Genetic engineering, like so many other breakthroughs, raises important ethical and political questions. In recent years the National Museum of American History has tried to show both the technical and social side of scientific advance. (photo credit p04.4)

This chapter focuses on how the Smithsonian came to build a “palace of progress” on the National Mall. Politics and personalities shaped the way the National Museum told the story of science and technology. So too did changes in American culture: the conquering of the West and the related popular fascination with “vanishing” Native Americans; enthusiasm for technology at the turn of the twentieth century, when electricity and the telephone were changing American lives; world war concerns and Cold War fears; the questioning of technology in the 1960s and 1970s; and the fascination with electronics and computers in the 1990s. As a result of these social and cultural changes, the meaning of progress itself has changed, gaining new inflections and evoking different ideas. All along, the Smithsonian has reflected and helped shape the way Americans thought about science and technology.