From Artifacts to America

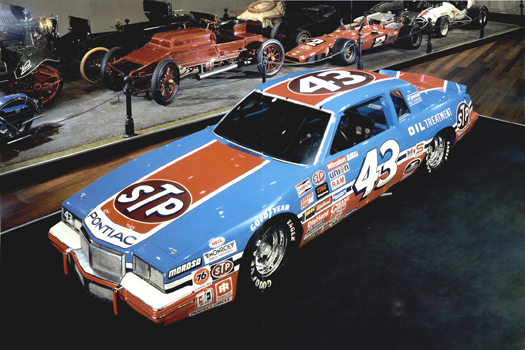

NASCAR stock car driven by Richard Petty during his 200th Grand National victory, July 4, 1984. The title for this Pontiac racing car was transferred to the National Museum of American History at the Talladega Speedway in Alabama, several weeks after Petty won his 200th Grand National race. The first NASCAR stock car to enter the museum collections, the Petty car is one of several vehicles curators have collected to represent the popular sport of automobile racing. (photo credit p06.1)

When objects come into the museum, they are transformed in many ways. But they also have the power to transform us. By revealing new truths and telling new stories, they can enrich, challenge, and change our understanding of American history. And in changing our view of the past, they can also change our view of ourselves.

THIS BOOK HAS FOCUSED on how various artifacts have come to be in the National Museum of American History, recounting the ideas and circumstances—and sometimes struggles and debates—that brought them into the collections. The museum’s artifacts reflect changes in what we Americans have valued, whom we have honored, how we have related the past to the present, and how we have seen ourselves as a nation. They document the ways individuals and groups have used the Smithsonian to lay claim to the American heritage, to insert themselves into the national story, and to promote, defend, or challenge traditional notions of American identity.

As focal points for debates and declarations about what is important and who is included in American history, museum objects embody struggles for power, authority, and recognition. In seeking a place for their cherished objects in the nation’s museum, diverse individuals and communities have sought to contribute to the Smithsonian’s national legacy their own beliefs about what it means to be American. The museum’s artifacts therefore represent more than just “the past”: they capture particular ideas about the past and about American identity. Their collective story tells a history of American history.

Of course, as far as the museum is concerned, deciding what to collect is just the beginning. Once artifacts arrive, they present curators with a host of new challenges. As new additions to the collection, they must be identified, numbered, and catalogued. As physical objects, they need space to be stored. And as old and fragile things, they require special care and treatment to survive. But most of all, artifacts in the museum demand to be put back into history. They want to tell their stories, to be made meaningful again.

Shoes worn during the voting rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, 1965. Juanita T. Williams, a civil rights activist, wore these shoes when she and twenty-five thousand other protesters marched the fifty-four miles from Selma to Montgomery to demand equal voting rights for African Americans in March 1965. Since 1975 Williams’s shoes and other mementos of the Selma march have been displayed in the National Museum of American History to help tell the story of African Americans’ struggle for freedom and citizenship. (photo credit p06.2)

This final chapter is about how the museum puts artifacts back into history. It explores the vital process of interpretation, through which old artifacts take on new meanings as part of larger historical stories In looking at the way the museum has interpreted its collections over time, one fact is especially worth noting: the same object is never put back into history in exactly the same way. While an object may have been collected to tell one story, eventually it will be analyzed from a different perspective or placed in a different context; it will tell a new story. Through this ongoing process of interpretation and reinterpretation, the museum reveals the fundamental value of artifacts as links to the American past. More than a place where artifacts are preserved, the museum is a place to discover why artifacts matter.