We spend most of our waking hours at work and, in many workplaces, the majority of that time is spent staring at screens. One particular medium has come to dominate office communication: email. It’s probably the first thing you check when you start your work day, and the last thing you do before you leave. It is the bane of the modern condition, and on that basis it is here that we shall begin our study of digital etiquette.

Things weren’t always like this. Email has its roots way back before the internet as we know it, when American programmer Ray Tomlinson wrote some code that allowed users to send messages between computers on the ARPANET system (the precursor to today’s internet) in the early 1970s. Tomlinson, who died in 2016, said he developed the system because it ‘seemed like a neat idea’ and maintained that the first emails he sent were so insignificant he had forgotten them.1 I’m sure we can all relate.

It’s undeniable that email has had a transformative effect on work culture. Without it, we’d never know the joy of working remotely, sharing ideas across continents, or passive-aggressively CCing the boss when dealing with an annoying colleague. But I think we can all agree that email is completely out of control. It no longer helps us do work; it is work. It may have freed us from the physical confines of the office, but mentally we can never leave. Email is distracting, time-consuming and intensely stressful.

This is where etiquette can help. The majority of the stress around email can be attributed to a lack of consensus on how to use it. How quickly must you respond to an email? How do you strike the right tone? And is there a law somewhere that says every message must begin ‘Sorry for the late response’?

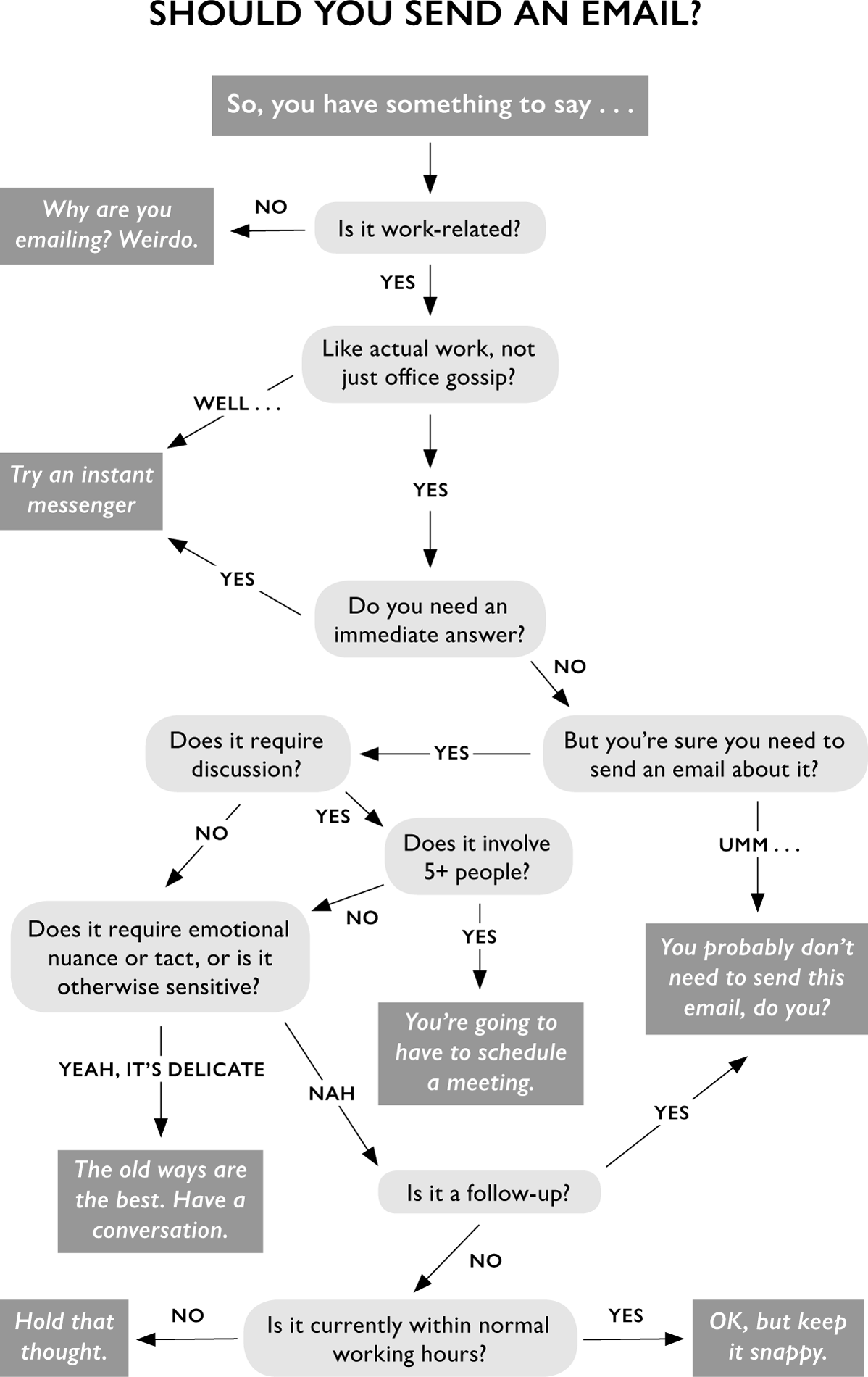

Together we shall dissect the ins-and-outs of proper email protocol, from subject line to sign-off. We shall resolve once and for all when email is the correct medium to use and consider alternative workplace communications such as conference calls, instant messaging tools and (steel yourself) LinkedIn. Once you’re done with this chapter, just leave it lying conveniently open on the desk of that one person in the office who still hasn’t got their head around the unwritten rules of reply-all.

Office email

The paradox of email is that it’s simultaneously very convenient and utterly exhausting. It’s often the most expedient way of getting things done, and yet it just seems to take up so much time.

If you’re feeling the crunch, you’re not alone. In one study presented at a conference in 2016, researchers asked 40 office workers to wear a heart rate monitor for 12 days and log their computer use during this time. The workers checked their email an average of 77 times a day and spent almost an hour and a half dealing with it. Sure enough, their heart data showed that the longer they spent on email within a given hour, the more stressed they were during that time. And the longer they spent on email each day, the less productive they felt they had been.2

Given that email is such a universal horror, good email etiquette really revolves around one thing: reducing it as much as possible. A considerate emailer strives to take up as little of their recipient’s time and energy as they can. They email only when strictly necessary and take pains to make their messages as easy to deal with as possible. A considerate emailer understands that the best email is the one they don’t actually send.

THE LIFE-CHANGING MAGIC OF TIDYING UP (YOUR INBOX)

Before you can even think about sending emails to other people, you need to get your own house in order. After all, you can’t hope to reduce the greater burden of email on the world if your own inbox is a digital dumping ground that threatens to engulf you with the next ‘ping!’ of a notification. And if you’re barely treading water in a quicksand of unread messages, you could easily miss the one you actually need to respond to.

Do a quick internet search and you’ll find that email management strategies are as abundant and diverse as fad diets – often with similarly unsatisfying results. There are entire self-help books dedicated to this topic, of which this is not one, so I’ll cut to the chase and give you the only advice you need to bother with.

Sound too good to be true? Let me introduce you to Inbox Zero.

I am an Inbox Zero disciple. Those of us who have found inner inbox peace just can’t stop ourselves from evangelising on the matter in an effort to save other poor souls from email purgatory. In my job as a magazine editor, I once found myself having to entertain a famous sports star ahead of a photo shoot. These forced moments of interaction are always stilted, and the conversation soon petered out into awkward silence – until: ‘Have you heard about Inbox Zero?’ I asked. (He had not, but I think I converted him.)

So what is Inbox Zero? The term was coined by blogger, podcaster and all-round productivity type Merlin Mann, who first laid out the strategy in several posts on his 43 Folders blog in 2006 and then in a Google Tech Talk in 2007. In these, Mann shares a simple way to triage your emails so they don’t keep stacking up. Think of him like Japanese tidying-up guru Marie Kondo, except he’s helping declutter your inbox instead of your sock drawer.

The driving idea of Inbox Zero is to keep your inbox empty by processing every email in some way as soon as you read it.

A few clarifications before you have a panic attack: this does not mean processing every email as soon as it arrives, nor does it mean answering every email. The point is that when you choose to read an email, you should do something with it, so that it doesn’t just keep haunting your inbox, making you feel guilty. ‘If I had to sum it up in one phrase, I would say that if you can find the time to check email, you must also use that time to do something with that email,’ Mann tells me.

Still not convinced? Follow these three simple steps to embark on your own life-changing journey:

1. Start with a clean slate

Depending on your current email habits, this may require quite a brutal deep-clean. The sensible, grown-up way to do this would be to take some time to sit down and click through each unread message, deleting or responding as appropriate until you’ve cleared the decks. But let’s be realistic. There’s only really one thing for it: select-all + delete. Done.

If you struggle to let things go, you could move all of your unread emails into a separate folder to go through at a later date, or archive them instead. But if these emails have been kicking around unread for a while, it’s unlikely they’re that important – and if they are, people will find a way to contact you. They’ll send another email. They’ll mention it next time they see you. They’ll call you on the phone (shudder).

Now, take a moment to revel in your new, squeaky-clean inbox. Congratulations, you have no new emails! Don’t get too comfortable, however, because now the real work starts.

2. Turn off notifications

Or at least most of them. One reason email is the scourge of our working lives is that it’s constantly distracting us from other things. You just get into your groove on a project and – ding! – your train of thought is rudely interrupted by Becky from finance, reminding you about the charity bake sale this afternoon. In one case study, researchers found that it took an average of 64 seconds for workers to get back on task after checking their email (and that’s not including the time spent actually reading or dealing with the emails).3 Check your inbox every ten minutes over an eight-hour stretch and that’s 50 minutes of your working day spent just getting your head back into the zone after switching tasks.

Check your email on your own terms instead. Set your inbox to retrieve email at a specific interval rather than every time a new message arrives.

3. Only read each email once

Whenever you do check your inbox, the important thing is that you actually do something with the contents. As per Mann’s mantra: ‘Your job is not to read an email and then read it again.’ Upon reading, he recommends immediately taking one of five actions: delete, delegate, respond, defer, do.

EXTRA EMAIL MANAGEMENT PRO-TIPS FOR THE TRUE INBOX NEAT-FREAK

Not got your fix? Keep your inbox spotless with these bonus techniques:

- ● Unsubscribe from all the newsletters you once enthusiastically signed up for but never actually read – these have a tendency to rapidly breed if left unsupervised.

- ● Set up automatic filters. Your email client probably already does this for spam, but you can set up your own rules to divert emails from certain senders or containing certain keywords straight to a designated folder, so they don’t clog your inbox.

- ● Organise inbox folders by deadline, not subject. This way you can easily prioritise the emails you’ve deferred.

- ● Stop people emailing you in the first place by making your email address hard to find. Says Mann: ‘Only an animal has their raw email address sitting out in public any more.’

The first one – ‘delete’ – is easy. If you have an email that is obviously rubbish, or that you don’t need to do anything with after reading, then just get rid of it. Archive it instead of deleting if you want to keep it for reference purposes. ‘Delegate’ is also pretty simple: if it’s someone else’s concern, forward the email and be done with it. And ‘respond’ isn’t as scary as it sounds. If an email requires a fast response, just do it.

Once you’ve completed these steps, you’ll probably be surprised at how little remains. The remaining emails – the ones that actually require some real work – fall into the ‘defer’ and ‘do’ categories. Choosing when and how to ‘defer’ is the trickiest. Mann suggests moving deferred emails into a specific ‘to do’ folder so that you can keep track of them without clogging your main inbox. Just be mindful that you also work through that folder regularly; lingering emails are still lingering emails, regardless of how diligently you’ve filed them.

Put these points into practice and you’ll wonder how you possibly managed before. Just one word of warning: it is possible to get a bit too carried away with keeping an empty inbox, to the point that it defeats the whole purpose of the exercise. After all, Mann says, ‘The point of this is not to obsess about getting to zero. The point is to do less obsessing.’

When to send an email

It used to be that you’d leave your desk at 5 p.m. and would be uncontactable until 9 a.m. the next morning. Now that we’re all carrying mini-computers in our pockets, however, there’s a general assumption that we should all be digitally reachable at just a moment’s notice.

But just because we can send emails at any time of the day or night doesn’t mean we should (indeed, knowing the difference between ‘can’ and ‘should’ is pretty much the definition of good manners).

So insidiously has work email crept into our private lives that France has gone so far as to legislate against it, granting workers a ‘right to disconnect’ (droit à la déconnexion) that essentially enshrines in law a French employee’s right to ignore their boss’s emails and calls. The law, which was passed in 2017, doesn’t dictate exactly how employers should restrict workers’ use of digital tools but stipulates that companies should come up with a policy, agreed with employees, to limit digital encroachment into workers’ personal and family lives. As I believe Robespierre once said: Liberté, égalité, email-free.

Of course, the problem with regulating out-of-hours email is that it’s very hard to stop people from picking up their messages, even if they know they technically have the right to ignore them. We’ve all now been conditioned to jump every time we feel a vibration in one of our pocketed regions, and while it’s one thing to know you don’t have to check your email, it’s another to shrug off that nagging feeling that you just might be missing something super-important as you watch message after message stack up.

INAPPROPRIATE PLACES I HAVE CHECKED MY WORK EMAIL

On holiday

At the family dinner table

Out with friends

On a first date

On a last date

Up a mountain

On the beach

In a Buddhist temple

On a ‘reconnecting with nature’ camping trip

In bed

In the bath

On the loo

After a few too many drinks

After many too many drinks

The onus is therefore on the sender to respect their recipient’s time. Stick to work hours wherever possible and avoid weekends and holidays. Be mindful that your recipient’s work hours may be different to yours; try to accommodate schedule or time zone differences as much as is reasonable. For bonus points, avoid emailing on Monday mornings and Friday afternoons, when no one will appreciate the disturbance.

Ah, you might say, but they don’t have to answer them straight away! I, the super-conscientious employee, just want to complete my to-do list and send all of my emails as soon as possible. I don’t mind putting in the extra time! In fact, I like answering emails in my pyjamas! And that way, I’m not keeping anyone waiting on my response – I’m doing them a favour!

No, you’re not, and your colleagues hate you.

This goes back to the paradox of email: here, you are enjoying the convenience of email while forcing the stress of it onto your recipient. Even if you’re not requiring or even expecting anyone to respond to your messages immediately, they will likely feel pressure to do so. By emailing at that time yourself, you have set an unreasonable norm – and in doing so you are exhibiting poor etiquette.

Still really want to write emails at an unsociable hour? Learn how to use your email service’s scheduling feature.

How quickly must you respond to an email?

If you were to ask anyone what constitutes good email etiquette, they would probably say something to the effect of ‘responding promptly’. But what exactly counts as ‘prompt’?

This is one of the main sources of email stress. Because there are no real established norms around how swiftly you should reply, we all feel obliged to do so as soon as possible – even though the whole point of email is that it’s asynchronous.

If you’re following Inbox Zero, you should be able to turn around simple emails without much delay, and at least within a day. The problem comes when you need to provide a longer response or complete some kind of task before replying.

While there’s no one-stop answer as to how long you can leave people waiting, there is an easy workaround: ask them. People have a misguided assumption that etiquette must be unspoken, but transparency is often the best way to ward off potential misunderstandings. If you’re not sure when your full response is needed, reply first to confirm a deadline and make sure you’re on the same page. All you need to say is something like, ‘Is it OK if I get this to you tomorrow?’ or ‘I plan to have this with you by Monday,’ or ‘I need to think about this – when do you need my answer?’

It’s also true that fast replies are not always the best etiquette. There can be considerable advantages to delaying a response, particularly if you’re on an email thread with multiple people. Here, it’s often better to hold back a while and see how things play out. It may be that your input is not even needed in the end – and you can rest safe in the knowledge that you just decreased the world’s email traffic by one more message.

When to send an email, part 2

Before you put fingertips to keyboard, stop and think: is email really the right medium for this message? In most workplaces, email has become the default means of getting anything done, but it shouldn’t be. Indeed, the same qualities that make email perfect for some tasks make it terrible for others.

Email is good for non-urgent communications and simple back-and-forths. It’s good for sharing documents, starting a paper trail and distributing information to lots of people at once.

Here’s what it’s not good for:

- ● Immediate responses. A key selling point of email is its asynchrony; you can send an email at one time and your recipient can pick it up whenever is convenient to them. This means that you can’t assume you’ll get an immediate answer. Sometimes it’s better to text, instant message, shout across the room or (gasp) pick up the phone.

- ● Nuance. It’s hard to express tone over email. Efficiency can easily be misinterpreted as aloofness and politeness can come across as standoffish. Anything that requires a bit of tact or delicacy is best suited to a medium where you can use verbal and non-verbal cues (i.e. old-fashioned talking) to make sure your meaning gets across.

- ● Discussion and debate. Email is not a discursive medium. Long email threads between multiple parties can quickly get confusing, with everyone weighing in and no one sure what their role in the discussion is meant to be. If you need to have a group debate or come to a joint decision, schedule a meeting – and email a memo round afterwards.

- ● Confidences. There’s no deleting an email once it’s sent, and after that it’s completely out of your control. An email can be forwarded to anyone without you knowing, so stick to in-person meetings if it’s a sensitive subject. Keep in mind that your work email is not private: your company likely has access to it, and there’s always the chance you could be hacked. Keep it professional.

EMAIL ALTERNATIVES

The phone call

What’s worse than a work email? A work phone call.

That’s not strictly true. In the correct circumstances, a phone call can be the best way to get something done. It’s faster than email and benefits from tone of voice, making it much better suited to back-and-forth discussions and more sensitive situations. You can ask a question and they answer – no need for a 12-part email chain and frantic analyses of whether the fact they only sent a one-line response means they hate you or they’re just a bit busy.

No, the problem is unscheduled phone calls. You’re settling down at your computer, you’re just getting in the zone – and your desk phone starts ringing with an unrecognised number. The horror. The solution is simple: if you want to call someone, set a time first. There’s nothing worse than scrambling to pick up the receiver before the ringing disturbs your coworkers, only to find it’s someone you don’t want to speak to, wanting to have a conversation you’re not ready to have. Advance notice means you can both carve out time in your diaries and make sure you’re prepared. (The exception is if it’s genuinely urgent and you only need a really quick answer – phone calls under a minute get a free pass.)

If someone calls out of the blue asking to speak to a colleague, there is only ever one correct response, even if they’re sat right next to you:

‘Oh I’m sorry, they’re in a meeting – shall I let them know you called?’

Voicemails

While the phone call has its merits, the voicemail has none. It’s entirely redundant. It’s calling to say you called. On top of that, it’s useless as a means of conveying any actual information. It takes about 60 times longer to check than an email, and you always get to that part halfway through where someone starts reciting their phone number, you scramble for a pen, fumble to note it down – wait, was that 6-2-3 or 6-3-2? – and have to start the whole recording from the top. It’s a waste of everyone’s time.

If you can’t get through to someone on the phone and want to leave a message, there are many more effective ways. Write an email. Send a text. Scribble a Post-it Note. Write a message, stick it into a bottle and drop it down the nearest drain.

THINGS I’D RATHER DO THAN CHECK MY VOICEMAIL

Answer all my emails

File my expenses

Share an ‘interesting fact’ about myself at the start of a meeting

Write in Comic Sans for a week

Fix the office printer

Staple my finger

Clean the coffee machine

Volunteer for the work fun run

Offer to organise the Christmas party

Pay someone else to check my voicemail

Conference calls

If you don’t like phone calls, try doing it with six people on the line.

Every conference call starts roughly the same way. First you have at least five minutes of saying hello, which tends to go something like this:

You have entered the conference call.

‘Hi! Is that John?’

‘No, it’s Janet.’

‘Hi Janet! This is Nell.’

‘Hi Nell!’

‘Hi Janet! This is Bob.’

‘Hi Bob!’

‘So are we just waiting on John?’

‘Yes, we’re just waiting for John.’

‘Does he have the login?’

‘I’ll send him a note.’

‘…’

‘Maybe we should get started and he can join later. Janet, do you want to begin?’

‘Sure, let me just start by saying –’

‘Hi, this is John.’

‘Hi John! This is Nell.’

‘Hi Nell!’

‘Hi John! This is Bob.’

‘Hi Bob!’

‘Hi John! This is Janet.’

‘Hi Janet!’

‘Janet was just about to get started …’

Once everyone has joined, you are allowed exactly one comment about the weather, after which all small talk is banned. Try not to talk over each other; remember that people dialing in internationally may have a slight delay in response. Stick to the time allotted for the call, and remember to leave a few minutes for the extended goodbyes:

‘OK great, thank you!’

‘No, thank you.’

‘Thanks everyone.’

‘OK, thanks, bye.’

‘Bye.’

‘Yes, bye.’

‘And thanks.’

‘Thank you.’

‘Bye.’

‘Speak soon.’

‘Looking forward to it.’

‘Bye.’

(Repeat ad infinitum until someone finally builds up the courage to put down the receiver first.)

To avoid the above, conference calls should be used sparingly and kept to the minimum number of people possible.

HOW TO WRITE AN EMAIL (YES, REALLY)

So, you’re ready to write an email. You’ve thought about it, you’re sure that email is the best medium, and you’re ready to compose.

First of all, let’s recap that golden rule of email etiquette: everything you do should be in service of reducing the burden of email on your recipient. Concision and clarity are your guiding principles.

In this respect, emails diverge significantly from traditional letter-writing protocol. When writing a letter, you would usually expect to open with some small talk, ask after your correspondent’s health, thank them for their previous letter, and so on; launching straight into whatever you want from that person would be considered rather abrupt.

Email turns this on its head. It’s perfectly fine – indeed preferable – to get straight to it. Far from being impolite, brevity in email shows a respect for your reader’s time. Merlin Mann has some solid advice on this: ‘Assume that everyone you’re communicating with is smarter than you and cares more than you and is busier than you.’

If you’re emailing in a business context, you are probably doing so out of necessity, not nicety; you don’t need to try to disguise that fact with generic pleasantries, which will likely only come off as inauthentic anyway. Unless you have a genuine reason to be concerned about your recipient’s wellbeing, there is no need to start your message with ‘How are you?’

Making your email as easy as possible for your recipient to deal with means being crystal clear about what you’re asking and, crucially, what action you expect the other person to take. If you need a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer, make sure there’s a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ question. Include all the necessary information in your first email, so that you don’t end up drawing it out into a string of back-and-forth messages. If you need to set up a meeting, don’t just say you need to set up a meeting; suggest a specific time and place.

Then, wrap it up. Web designer Mike Davidson holds that no email needs to be longer than five sentences long. In 2007, he set up the website five.sentenc.es, which encourages people to adopt a five-sentence limit and copy a link to the website in their email signature to explain the brevity to recipients (there’s also a four.sentenc.es, three.sentenc.es and even two.sentenc.es for those who like a challenge). If it sounds a bit restrictive, give it a try. You’ll likely find that you can respond to most things in that space. If you have to scroll your screen to get to the end of a message, it’s probably too long.

Subject lines

A subject line could be the difference between someone reading your email and ignoring it, so put a bit of thought into it. Keep it short and obvious: your reader should be able to tell from the subject line what they can expect from the rest of the email. Remember it will likely be read on mobile, so you can probably fit a maximum of around six words before it gets cut off.

Never leave the subject line blank; that’s just rude. Don’t put the whole message in the subject line and leave the email blank; that’s a text message. And unless you’re sending out a mass-marketing email (which: don’t), don’t try to be funny and definitely don’t try to fool people into opening your email with clickbait headlines or sneaky ruses. The worst trick I’ve seen is a marketer starting the subject ‘Re:’ to make it look as if they were responding to an email I’d already sent. Do not do this. Yes, your recipient may be duped into opening the email, but you can bet they will angry-delete it in less time than it took you to type those two letters.

If the email is urgent, you may note that in the subject – but exercise restraint. Each time you play the ‘urgent’ card, you’re decreasing its value. You can also use electronic labels to flag an email’s level of importance, but it’s best to avoid this unless absolutely critical. If something were unimportant, you presumably wouldn’t be sending an email about it in the first place (and if you would, go back and start this chapter again, as you clearly haven’t been paying attention.)

How to begin

You don’t need to use a greeting every time you send an email. Greet your recipient in the first email, but if it turns into a back-and-forth thread, treat it like a conversation – you don’t have to keep interjecting with ‘hello’ every time it’s your turn to speak.

How you greet someone depends on how well you know them and the level of formality required for the situation. A lawyer is probably going to have a different standard protocol to a nightclub owner. Honestly, ‘Hi’ is usually fine. In particularly formal contexts, err on the side of formality and use ‘Dear’ the first time, then take the age-old etiquette shortcut and simply follow the other person’s lead. For close colleagues, you can keep things informal.

Always use someone’s name if you can, and for goodness’ sake make sure you spell it correctly. I go by Victoria or Vicki, but I’ve regularly been Viktoria, Vicky, Vikki, Vickey and Victor (and once, for some reason, Hazel). It’s usually fine to address people on a first-name basis, but go for their title and surname in more official business dealings, or if you want to show a higher degree of respect for their position. It’s a good idea to use someone’s full title first time round if it’s anything other than Mr/Mrs/Ms/Miss, as in Lord, Lady, Sir, Dame, Dr, Professor and so on – some people can be quite particular about that.

‘To whom it may concern’ or ‘Dear Sir or Madam’ (or worse, ‘Dear Sirs’) only make it look as if you haven’t done your homework, or have copy-pasted the same email to a bunch of different people. Why should someone bother reading your email if you don’t even know who you’re writing it to? The same goes for referring to someone by their job title. If you really can’t find out the person’s name, you’re probably best just sticking to ‘Hi’.

How do you address an email to the Queen?

You don’t. You send a snail-mail letter to her private secretary.

Striking the right tone

It’s notoriously difficult to convey tone in email. You don’t have the benefit of non-verbal cues such as facial expression, tone of voice or body language, so you need to use your words to make your intentions as clear as possible.

A common mistake is to try to be too polite, which can end up back-firing and appearing haughty and aloof. Consider the following example:

‘Please could you get back to me by Friday?’

It’s perfectly respectful, clear, and gets the point across with minimal fuss. Now, consider the same sentiment wrapped up in more formal language:

‘I would be much obliged if you could kindly respond to this message at your earliest convenience.’

This is unhelpful, unspecific and makes you sound like a pompous arse.

USEFUL TRANSLATIONS OF COMMON EMAIL PHRASES

‘Apologies for the delayed response.’ – It’s just the law that you have to write this at the start of every email.

‘Hope you’re well.’ – Small talk over, now let me list my demands.

‘Just following up/checking in/touching base/circling back.’ – Oi, why haven’t you replied to this yet?

‘Not sure if you saw my last message …’ – You definitely saw my last message.

‘Did I miss your response?’ – We both know I didn’t.

‘Sorry to chase …’ – Sorry not sorry.

‘As per my previous email …’ – Keep up, slowpoke.

‘To be clear …’ – How are you still not getting this?

‘Does that make sense?’ – Are you stupid?

‘Let me know if you have any questions.’ – Don’t.

‘Thanks in advance.’ – Just so we’re clear, you have absolutely no choice about whether to do this or not.

‘It’d be great to hear back from you asap.’ – Like, yesterday.

In praise of concision, or how to email like a CEO

There’s concise, and then there’s concise. In 2017, Buzzfeed writer Katie Notopoulos decided to try what she calls ‘emailing like a CEO’ – answering every message almost instantly, but with a very short response.4

Notopoulos says that she first picked up on this trend when emailing CEOs in her role as a tech and business reporter. Mark Cuban, owner of the Dallas Mavericks basketball team and one of the investors on US TV series Shark Tank, has a reputation for emailing quick, one-word responses, and she noticed that her editor-in-chief took a similar approach in his emails to her. So, she decided to give it a go. ‘I thought it’d be a fun stunt to write about, but I also thought it might be helpful for myself,’ she says.

The key to emailing like a CEO is to respond as quickly as possible and get straight to the point, with absolutely zero preamble. It could be just one or two words. ‘Thanks.’ ‘OK.’ ‘What’s the latest?’ Grammar is optional. Amazon’s Jeff Bezos takes things even further, reportedly making a habit of forwarding customer emails to his employees with a single character: ‘?’

Notopoulos did this for a week, and found that it made a big difference. ‘It was great,’ she says. ‘I didn’t realise how much email hung over my head like a little dark storm cloud all day long.’ She says she felt more productive and less stressed, and not just when it came to email: ‘I felt so productive dealing with my inbox that I also felt like I was more productive in the other work that I was doing.’

Notopoulos has kept up the habit as much as possible. Where she used to read emails on her phone, then wait until she was at a computer to answer them, she now treats them more like tweets, prioritising a rapid response over a perfectly composed one. ‘It’s much better to actually get it done than it is to have it worded perfectly,’ she says. She sometimes just uses the suggested replies on Gmail – those chipper automated responses based on an AI analysis of an email’s content.

A note of caution, however: emailing like a boss might make you feel more zen, but it’s not always appropriate. There’s a thin line between a short response and a terse response. Someone you work with every day is probably fine with you responding in a word or two, but less well-known senders merit a few more niceties. Just because you’re being concise doesn’t mean you can neglect your pleases and thank-yous.

Notopoulos admits that emailing like a CEO won’t work for everyone. People with jobs in sales or customer service, for example, may have to sacrifice some efficiency for a higher level of courtesy. There’s also a power dynamic at play here: perhaps this is ‘emailing like a CEO’ because only the CEO can get away with it. As Notopoulos says: ‘Being the boss or being the CEO affords you the ability to be slightly rude to your underlings over email.’

Corporate jargon

Another aspect of email that sometimes needs to be decoded – and, frankly, that should be avoided as much as possible – is corporate jargon. The corporate jargoneer is in many ways the opposite of the ‘CEO emailer’. Rather than keeping things brief, he (and it’s usually a he) sees each email as an official missive to be carefully crafted using as many fancy-sounding professional phrases as possible, so that you end up with a lot of words that say nothing at all. He writes as if his whole vocabulary comes from the ‘business books’ section on Amazon. He uses words like ‘synergy’ and ‘blue-sky thinking’ unironically. He sporadically capitalises words that aren’t proper nouns. He uses ‘action’ as a transitive verb.

Some corporate jargoneers don’t even limit themselves to email. One of the worst I’ve come across was at a dinner party, when I asked a fellow guest what he did for a living and he described himself as an ‘architect’. What did he design? ‘Solutions.’ After a bit of careful probing, I found out that he was, in fact, a management consultant.

Avoid corporate buzzwords and clichés at all costs. They are the antithesis of concision and clarity, and make you look like you’re trying way too hard.

Corporate jargon bingo

Received an email from a corporate jargon waffler? See if you can get a full house!

| thesaurus abuse | an acronym you don’t recognise | noun used as a verb | ‘synergy’ |

| ‘think outside the box’ | portmanteau they just thought up | things aren’t bad, they’re ‘sub-optimal’ | ‘innovate’ |

| more than one $20 word | calls people ‘assets’ | ‘110%’ | randomly capitalised word |

| shoehorns in company slogan | appoints self spokesperson for a larger group | ‘disrupt’ | overly formal sign-off |

| insincere thanks | mixed metaphor | Steve Jobs reference | male author |

Sorry, just one more thing

A final point on email language: don’t pepper your messages with pointless qualifiers. There’s a common tendency, particularly among women, to try to ‘soften’ emails with words like ‘just’ or ‘sorry’ or ‘actually’ or ‘I think’ (or ‘Sorry, I just think that actually …’). But while you may think you’re being polite, this can have the effect of undermining your message.

In 2015, tech worker Tami Reiss built a plugin for Gmail called Just Not Sorry, which automatically highlights these qualifiers, like a spell-checker for self-doubt. She explains that she originally came up with the idea after having brunch with some other female businesswomen. They watched an Amy Schumer skit in which the comedian plays a scientist who struggles to talk about her work through constant unnecessary apologies. ‘I said, “I want help when it comes to stopping saying sorry,”’ recalls Reiss, who now works as a product lead at business platform Justworks. ‘I want to stop saying sorry.’

Women have been socially conditioned to act submissive and meek, to be stereotypically ladylike and to reflect this in our speech. We’ve been taught to apologise for everything – sorry for interrupting, sorry that you spilled your coffee on me, sorry for taking up space, sorry just in case. We’re apologising for existing.

Not only is this unnecessary, but it can make you look less capable and confident, not to mention that it diminishes the power of the word ‘sorry’ when you actually mean it. It also sets you up on the wrong side of a power imbalance, immediately positioning you as the weaker party. ‘If I show up late to a meeting and I say, “Oh, I’m so sorry I’m late,” the power dynamic immediately sends a signal that you are more important than I am,’ Reiss says. ‘If I show up and I say, “Thanks so much for waiting for me” the power dynamic is completely inverted – you waited for me.’

Say sorry when you need to, but don’t temper your message to massage other people’s egos. Good etiquette does not mean being a pushover, and you can be confident and direct without being rude.

Signing off

There is no good way to sign off an email, so just go for ‘Best wishes’ or ‘Best’. Yes it’s bland, yes it’s boring, but it is inoffensive, balances being formal enough without being pretentious, and is therefore the best option out of a decidedly bad bunch.

‘Thanks’ isn’t terrible, but can be a bit presumptive. ‘Thanks in advance’ is just rude (you might as well write, ‘Try getting out of that one now’). ‘Kind regards’ or ‘Best regards’ is unnecessarily staid for most emails. You could use ‘Yours faithfully’ or ‘Yours sincerely’ if you’re writing an email like an official letter, but this is only really necessary for particularly formal occasions, such as a cover letter for a job application. ‘Cheers’, ‘Ciao’, ‘Ta’ and so on are fine for close colleagues but not for people you don’t know well.

Follow-ups

The three ugliest words in the English language are ‘just following up’. (The three most beautiful, if you’re wondering: ‘unsubscribe from list’.)

These annoying little chasers always claim to be ‘just’ following up or touching base or checking in or circling back, or whatever, as if it’s no big deal – ‘just’ following up! In fact, of course, they’re clearly designed to purposefully ramp up the pressure and make you feel guilty for not already responding.

WHAT YOUR DEFAULT EMAIL SIGN-OFF SAYS ABOUT YOU

Best wishes – You are normal. You don’t rock the boat. You are utterly unremarkable (which, in a business context, is entirely appropriate).

Best – You are also normal, if a little more time-pressed.

BW – You’ve taken a perfectly acceptable sign-off and turned it into an abomination. Do you still use text speak in your text messages too?

All the best/All my best – You’ve actively thought about your email sign-off. You really want to do something different, but you can’t quite bring yourself to stray too far from the norm.

Kind regards – You’re a bit socially awkward. Your idea of dress-down Friday is slightly loosening your tie.

Yours faithfully/Yours sincerely – You’re desperate to sound sophisticated, but you just come across as a bit of a tool.

Cheers – You’re the joker of the office. You tell people that you don’t have colleagues, you have ‘friends that you work with’.

Ta – You’re northern.

Love from – You’re either under ten years old or an HR incident waiting to happen.

Greetings – You are an alien. You come in peace.

Avoid sending follow-ups. Frankly, they’re unflattering, making you look at best demanding and at worst desperate. If you need to give someone a nudge, then get straight to the point and be clear about what you’re after. As Tami Reiss puts it: ‘You’re not just checking in, you’re checking in for a reason. If you’re just checking in? You’re not my mother.’

If you absolutely have to chase a response, you get one shot at it. One. By sending a follow-up, you’ve just doubled your imposition on someone else’s inbox. If you still don’t get a response, it’s time to face the facts: they’re just not interested.

THE FINER DETAILS

How to use CC

Oh, how much easier life would be if we could all agree on how to use CC.

Here’s the deal:

- ● The ‘to’ field is for the primary recipients of the email, who are expected to respond.

- ● The ‘CC’ field is for people who need to see the email for reference only and don’t need to respond.

So many people seem unable to grasp this, but it makes email so much easier. If you’re in the ‘to’ field, you should respond; if you’re on CC, don’t. The most recent edition of the famous Debrett’s etiquette handbook dedicates just two pages to the topic of digital communication (about the same as it has on how to address a bishop), yet even it makes room for this crucial distinction. Repeat it after me, write it in your diary, tattoo it on your arm: this is how to use CC.

When is it necessary to include people on CC? In aid of eliminating email excess, you should limit the number of recipients on an email to as few as possible, but there are some situations in which a CC is a necessary courtesy. If you’re referring directly to someone in an email, it’s polite to copy them in; no one likes to feel others are talking about them behind their back. If you’re sending an email about a group project, CC the other members of the team so no one feels left out. Aside from these situations, be judicious. CCs can be like party invitations if you’re not careful – send one to one person and suddenly you feel obliged to add everyone else in the same group. Before you know it, the guest list is over capacity, the bar has run dry, and no one can remember the reason they’re gathered there in the first place.

And while CC can be a nice email courtesy, it can also go the other way. If you’re mid-email-chain with one person and suddenly throw in a third party on CC, you risk breaking the rapport. Be particularly mindful if the conversation is at all personal in nature; remember that anyone you loop in will be able to read past messages in the email thread.

In some cases, abuse of the CC field can be downright rude. Ever received an email asking you to do something, or complaining about how you’ve handled something, where the sender has oh-so-thoughtfully decided to copy in your boss? This is what I believe in Etiquette-land they call ‘a dick move’.

Copying in someone’s supervisor undermines them, as it basically says that you don’t trust them to deal with the issue themselves. It can even come across as a kind of blackmail – ‘Don’t respond how I want you to and you’ll be in trouble!’ I once worked with a man who insisted on CCing my male colleague into every email he sent me, even though he had been informed multiple times it was my responsibility to deal with him (more’s the pity). Don’t be that asshole.

When, if at all, to BCC

Using BCC, CC’s sneaky sibling, is playing with etiquette fire. The ‘B’ in BCC stands for ‘blind’, and it means that the primary recipient of your email will not see that you have copied someone else into the correspondence. They are a silent witness.

Sneakiness is generally poor etiquette, and you should avoid using BCC most of the time. If you really need to loop someone into an email confidentially, for example to establish a paper trail, Debrett’s has you covered: instead of blind-copying, ‘the email should be forwarded on to the third party, with a short note explaining any confidentiality, after its distribution’.5

That said, as with CC, there are a few circumstances in which BCC is not only acceptable but admirable:

- ● When you’re emailing a group of people and don’t want to reveal their identities and/or email addresses to everyone else in the group. In these situations, you should send the email to yourself and BCC everyone else. This is good etiquette, as you generally shouldn’t hand out someone else’s email address without permission. There are also cases where attaching someone’s name to a group email may be sensitive, compromising or even illegal. In 2016, a London NHS trust was fined for revealing the names of 730 people who used an HIV service, after a staff member accidentally put all the recipients in the ‘to’ field instead of BCC. Yikes.

- ● When you’re sending a mass email and want to avoid a reply-allpocalypse (see below). The advantage here is that someone on BCC cannot reply to other people on BCC, so you prevent a mass discussion from breaking out among respondents.

- ● When you’re employing BCC in the service of saving another person’s inbox. This is a truly noble etiquette manoeuvre whereby you remove someone from an email chain without just cutting them off cold. Here’s how it works: let’s say someone includes your colleague on an email, but you know they don’t need to be part of the discussion. Instead of replying all, you can reply to the sender and move your colleague to the BCC field. This means that they will see your response – and know that you have things under control – but won’t be disturbed by any further messages. When you do this, state in the email copy that you’re moving them to BCC, so everyone’s on the same page. For example: ‘Hi Sophie, I’ll deal with this – moving Caroline to BCC to save her inbox.’ It’s the ultimate act of email etiquette self-sacrifice.

Replies vs reply-all

When to reply or reply-all is an important judgement call. On the one hand, you don’t want to needlessly hit reply-all and bring more unnecessary email into the world. On the other, you don’t want to look underhand, or like you’re talking about people behind their backs.

If reply-all is the norm on a particular email thread, then you should follow suit (but remember the rules of CC – no need to reply at all if you’re only on CC). If you are sending an email to lots of people seeking individual input, do your bit to establish good reply hygiene by explicitly stating in the email that responses should be sent off-thread. It’s likely many will ignore this, but if enough of us keep fighting the good fight, we might eventually make some headway.

How to avoid a reply-allpocalypse

When reply-all goes wrong, it goes really wrong. A reply-allpocalypse usually occurs when someone accidentally addresses an email to a company distribution list, thus sending it to far more people than they intended. Many workplaces use lists like these to make it easy to email whole departments, or even the entire company, at once; you only have to type one email address to reach potentially thousands of people.

You know how it begins: someone accidentally sends an email to the wrong list. They meant to send it just to their team, but their finger slipped and they’ve sent it to the entire office. Oh, and all the global offices, too. It starts off innocently enough. Rather than just ignoring the email, someone decides to respond – not realising that their reply will also get disseminated to the all-office mailing list.

Sorry, I think you’ve sent this to the wrong email. I don’t think it’s meant for me.

Everyone now receives this message too. Another comes in.

Hi, this isn’t meant for me. Please can you take me off this thread.

Next, the automatic out-of-office responses start to ping back. The scale of the incident begins to make itself known.

I don’t think I’m supposed to be on this either! :)

Hi, I don’t even know who any of you are, I’m on here by mistake. Can you take me off this email?

Put the kettle on and make yourself comfortable, because the reply-all demon has now been summoned, and it will be holding your and everyone else’s inbox hostage for the foreseeable. As each reply comes in, more people see the original all-office email, and then the replies too. The penny starts to drop. Some bright spark will cling to the delusion that it’s still possible to get the situation under control.

Please can everyone just stop asking people to take them off this thread, as this only results in more emails.

Replies about not replying start to proliferate.

Everyone, just stop replying to this thread.

Lol you realise your reply is also a reply :)

The thread gains steam. Someone remembers you can send gifs by email. Memes begin to spread. The office is buzzing; the reply-all storm is now the only thing anyone can talk about in real life, too.

The pleas get increasingly angry. The all-caps come out. There are way too many exclamation marks for a professional context.

OH MY GOD, PLEASE TAKE ME OFF THIS THREAD!!!!!

There’s always someone who sees an opportunity in adversity:

Well while we’re all here (lol!) here’s a reminder about the charity fun run this weekend! It’s not too late to sign up!

By this point, the original sender has disappeared into a manager’s office somewhere with their head hung low. A terse official note makes the rounds.

Dear colleagues,

This email has been sent in error. Please DO NOT RESPOND to this email or any before it. IT are working on closing the thread down.

Could all staff please remember that the all-office email address is not to be used unless explicitly approved by a manager, as detailed in our email policy guidelines, attached here for your reference.

A few last replies filter through, and then the demon retreats. Until next time.

What should you do when you find yourself caught up in a reply-allpocalypse? A definitive answer can be found in a 2016 issue of the New York Times, which featured a story by reporter Daniel Victor with the headline, ‘When I’m Mistakenly Put on an Email Chain, Should I Hit “Reply All” Asking to Be Removed?’ The body of the article, reproduced here in full, read:

No.

Beneath that was a reporting credit: ‘The New York Times’s internal email system contributed to this report.’

If you find yourself a victim of a reply-allpocalypse, don’t reply. If you want to maintain your sanity, you can also set up an email rule to block the distribution list address, so that you don’t receive any further replies to it – at least until the storm has passed.

Meanwhile, just be glad you don’t work for a larger organisation. In 2016, a reply-allpocalypse hit the NHS (which apparently has some work to do on its email skills) when an administrator tried to set up a new distribution list for their unit, but ended up accidentally including every NHSmail account in England – all 840,000 of them. In a report following the incident, the NHS wrote that, ‘On an average day NHSmail handles between three and five million emails; but between 08:29 and 09:45 on 14 November the service received c.500 million which needed to be processed.’

THE THREE CIRCUMSTANCES UNDER WHICH IT IS APPROPRIATE TO SEND AN ALL-OFFICE EMAIL

- 1. When there’s a genuine emergency (‘There’s a fire’)

- 2. To convey a company-wide announcement (‘You’re all fired’)

- 3. Free food

Out-of-office replies

As you probably know, if you’re going to be away from your work email for a while, it’s a good idea to set up an out-of-office, or automatic reply. That way, when someone tries to email you, they’ll get an automated response explaining that you’re not at work, won’t be replying to email and frankly couldn’t give a hoot about their message.

The point of the out-of-office (OOO) is twofold. Firstly, it lets people know not to expect an answer to their questions, so they aren’t left hanging in digital limbo awaiting your response. Secondly, it absolves you of unread email guilt, as your inbox is left safe in the hands of an attentive robot. Ironically, it’s probably the only time that everyone who emails you will receive a timely response, albeit not a very useful one.

Your out-of-office message should contain a few crucial details – most importantly, the date you’ll be back. You may also wish to include the contact details for a colleague who is handling your work in your absence, but make sure you get their permission first.

Keep your message to the point. Corporate jargon has crept insidiously into the out-of-office response, so that suddenly everyone is informing you not that they’re on holiday, but that they’re on ‘annual leave’ – as if they’re embarking on some sort of transformative life experience and not just flopping on a beach in Mallorca for a week. Don’t go too far the other way, though – no one wants to get an auto-response gloating about how you’re ‘probably busy sipping pina coladas in the sun!’ while they’re scrambling to sort out whatever mess you left at the office.

Digital calendars

Digital calendars are a mainstay of office software suites, and can be very helpful to schedule and keep track of meetings and other events. But there are a few points of etiquette to remember. Please note that a calendar invite does not constitute an actual invitation. You need to include a message explaining to your recipient what the occasion is, and actually inviting them to it. Just inserting yourself into someone’s digital space by plonking an appointment in their diary is incredibly presumptuous.

Confirm the time and location of the meeting before you send a calendar invite; you shouldn’t change these after the fact unless it’s completely unavoidable. And please, don’t even think about using one of those infuriating scheduling apps that forces everyone to list every possible moment they potentially might be free over the next two weeks in order to find a mutually agreeable time to meet. If you’re organising an event, it’s on you to actually organise the event.

A LIFE BEYOND EMAIL? THE ETIQUETTE OF INSTANT MESSAGING

Could it be that there is an alternative to the horror show of email? In the past decade, instant messaging tools such as Slack have entered the workplace to try to pick up some of the slack (sorry) from our overflowing inboxes. Slack, and tools like it, are different from email in that they are intended solely for internal communications and put a focus on real-time messaging – think WhatsApp, but for work.

Slack is the Marmite of office tools. Some people love it, others loathe it, but whichever side of the debate you look at, I’ve never known people exhibit so much passionate feeling about a piece of enterprise software. For the lovers, Slack reduces inbox bloat, streamlines communication, and plays the role of a digital water-cooler to boot. For the loathers, it’s just email on steroids.

A couple of simple rules can mean the difference between your instant messenger being a time-saver or a time-suck. First, recognise what instant messaging is good for. Unlike email, it is ideal for quick answers and back-and-forth chat. It is not appropriate for information dumps or drawn-out discussions. Treat it like text messaging. Messages should be short, informal and relatively disposable.

Second, make sure you’ve set it up in a way that is conducive to productivity. Instant messengers let you send private messages to people, but a key selling point is group chats, or channels. The key to an effective channel is to be clear about what it is for and keep it limited to people who need to be in that group – like when you CC people on email.

But don’t get too excited; we’re not about to see the death of email any time soon. While I know plenty of offices that have started using instant messaging tools in the past few years, I haven’t heard of a single one that has stopped using email. As Slack co-founder and CTO Cal Henderson said onstage at a 2018 Wired event: ‘Email is the cockroach of the internet.’ It’s not going anywhere.

All the annoying people you’ll find on Slack

The backchanneller

The backchanneller has at least six chats open at any one time. While everyone is discussing something in the group channel, they’re sending you private messages to suss out your thoughts on the sly. You’re initially flattered that they value your views – until you realise they’re doing the same to everyone else too.

The meme fiend

Usually one of the younger team members, the meme fiend rarely responds in words, instead finding an animated gif for every occasion. You have to admit that it’s impressive how they manage to find a suitable image so quickly. Whether it’s always work-appropriate is another question.

The @all abuser

Most instant messengers have an option to push a notification out to all members of a channel, such as by tagging @all. It’s the Slack equivalent to reply-all and should thus be used very sparingly – but there’s always one person who gets a bit trigger-happy. ‘Hey @all anyone want a cup of tea?’ ‘@all anyone seen my mug?’ ‘Thanks @all I found it.’

The over-organiser

This is the kind of person who colour-codes their meeting notes and indexes their stationery drawer. On Slack, their organisational obsession expresses itself in creating channels for every possible group permutation, inventing a new one for each individual project so that every time you go to post you end up spending more time thinking about which channel you’re supposed to be writing in than what you’re actually going to say.

The late adopter

There’s always one office curmudgeon who drags their feet when it comes to new technologies. The late adopter is technically on the system, having begrudgingly signed up after a pointed email from the boss’s office, but when it comes to actually getting a response, you’d be more likely to get through to them by carrier pigeon.

One last thing on the subject of workplace communications: please stop inviting me to join your professional network on LinkedIn.

Most social media is best kept well away from office politics, but LinkedIn is the exception, focused as it is on professional connections rather than people you actually like. For many, the site is little more than an online CV dump; you make a profile when looking for your first job and return only when you need to update your experience (or, if you’ve failed to adequately filter your email preferences, then every single day when you receive an email breathlessly informing you that someone has viewed your profile, or that you appeared in 41 searches this week, or that you really ought to congratulate someone on their ‘work anniversary’, as if that’s a thing).

Aside from the occasional self-promotional update, most of us feel little urge to actually post on LinkedIn. For a special few, however, LinkedIn is not just a useful resource to occasionally check someone’s job title; it’s a way of life.

You know the ones: they usually describe themselves as an ‘entrepreneur’, ‘innovator’ or ‘thought leader’, but it’s never clear exactly how they make a living (bonus points if they use the term ‘digital nomad’). They collect LinkedIn endorsements with the keenness of a primary-schooler earning gold stars, and write prolific posts doling out business advice no one asked for, always with a liberal smattering of motivational hashtags.

They also often do that thing.

You know, that thing.

That thing where they type their post in simple sentences.

And separate each one.

With a line break between them.

Maybe because they think it makes them look important.

Maybe because they read that’s what Thought Leaders ought to do.

Or maybe just so that you’re forced …

… to click the ‘see more’ button.

When it comes to connecting with others over LinkedIn, people take one of two approaches: they either only connect with people they actually know, or they connect with anyone and everyone, racking up as many strangers as they can in their imaginary business network. Let’s get this clear: the first way is correct, the second is not.

But don’t just take my word for it. Ask Kat Boogaard, a freelance writer on the business beat who once wrote a piece for careers site The Muse in which she extolled the virtues of accepting every LinkedIn request. It broadens your horizons! she argued. It opens you to new opportunities! It gets your foot in the door! As long as people sent a personal note with their invitation, she wrote, she was willing to connect.6

A few months later, she realised her mistake and wrote a rebuttal to her own article.7 The problem was that, after she published the piece, everyone who read it tried to connect with her – and she couldn’t turn them away for fear of looking like a hypocrite. ‘Before I knew it, I had hundreds of requests from people I’d never met,’ she recalls.

THE BEST WAYS TO REACH

ME AT WORK, RANKED BY AVERAGE SPEED OF RESPONSE

- 1. Shouting across the office

- 2. Slack message

- 3. Phone call

- 4. Email

- 5. A meeting

- 6. Snail mail

- 7. Morse code

- 8. Omens in my coffee grinds

- 9. LinkedIn

- 10. Voicemail

Her LinkedIn became largely useless. She had a large network, but it was meaningless; most of the people she added weren’t even in her industry. Boogaard says that it put her off posting updates about her career or accomplishments – it seemed too weird to share that with strangers.

Keep your connections to people you know, or at the very least people who may have a shared professional interest. Many people don’t regularly check LinkedIn, so if you want to send a message, you’re much better trying to find their email than sending them an ‘InMail’.

Oh, and guys: don’t try to proposition people through LinkedIn. No, you don’t look suave in that suit. No, we’re not impressed by your job title. This is literally the least sexy place on the internet, and you are a creep.