As if communicating privately weren’t enough of an etiquette challenge, social media lets us all share our deepest thoughts, dankest memes and fleekest selfies with just about anyone – friends, followers, strangers, and that weird kid from high school who still likes all your Facebook posts.

Online communities date back to the beginning of the internet. It started with things like Usenet and bulletin boards, which worked in a similar way to what we now call online forums. The first social networking sites launched in the 1990s; readers who had their formative online experiences when the internet was still dial-up may recall looking up old school friends on Classmates or pouring out their teen angst in diary entries on LiveJournal.

Then came the noughties, and the rise of many of today’s biggest social media sites. LinkedIn was founded in May 2003, Facebook in 2004 and Twitter in 2006. For each platform that has stayed the course, others have gone out of fashion – RIP Friendster, Myspace and Bebo. The 2010s saw a rise in more image-focused sites and apps, including Instagram, Pinterest and Snapchat. (2011 also saw the launch of Google+, but people cared about that as much then as they do now.)

Every social media site is different. They offer different features, appeal to different audiences and have different expectations when it comes to behaviour. What is perfectly acceptable in one community may be unthinkable in another. We also use each platform differently; research looking at people’s profile pictures and written bios across platforms shows that we present different ‘personas’ on each one.1 Go to my LinkedIn and you’ll get the impression that I’m an accomplished professional. Follow me on Twitter and you’ll be blown away by my searing wit. Scroll through my Instagram and you’ll realise that, actually, I’m just a crazy cat lady.

All of this makes social media a digital etiquette minefield. What’s the difference between a friend and a ‘friend’? What are RTs if not endorsements? And what would Debrett’s have to say about memes? The stakes are high: play things right, and you could be propelled to online celebrity. Play them wrong, and you could be condemned to infamy. Just ask Milkshake Duck.

GETTING SET UP

Your profile on different social media platforms should reflect whichever side of you you wish to present in that milieu. Some, such as Facebook and LinkedIn, aim to reflect real-world relationships, and as such require or at least strongly encourage you to use your real name. Others take the opposite approach: anonymity is common on many forums and discussion groups, with most people choosing to go by a pseudonym. The good thing about anonymity is that it helps people feel free to express their real opinions. The bad thing about anonymity is that it helps people feel free to express their real opinions.

Twitter and Instagram fall somewhere in the middle, with some people opting to use their real names and others choosing to go by a nickname. Which you choose depends on the persona you want to portray. Are you posting as yourself? Your business? Or your comedy alter-ego, TheChucklingCupcake?

WHAT YOUR TWITTER BIO SAYS ABOUT YOU

‘Coffee’ as an interest – You’re basic.

Coffee-themed joke – Still basic.

A long list of interests and hobbies – You think you’re on Tinder.

Every place you’ve ever worked – You think you’re on LinkedIn.

‘Guru’, ‘ninja’, ‘rockstar’ – You need to get a real job.

‘Addict’, ‘junkie’, ‘aficionado’ – You’ve confused having a hobby with having a personality.

A list of cities next to the plane emoji – You’ve confused having money with having a personality.

‘Mummy to’/‘Daddy to’ – You’re on here before most people have woken up. You have strong views on breastfeeding.

‘Gamer’ – You’re a misogynist.

‘Patriot’ (not the sports team) – You’re a racist.

‘Jedi’ – You work in IT.

A meaningful quote – You’re either a 13-year-old girl or a business ‘evangelist’ (it’s often surprisingly hard to tell the difference).

A link to your Soundcloud – You still haven’t given up your dreams of being a rapper.

No bio – You’re either a nobody, or you’re Beyoncé.

‘Views my own’ – Don’t worry hun, you really aren’t as important as you think you are.

Like dating sites, many social media sites these days forgo an in-depth written profile, although it’s a good idea to add a short bio on platforms such as Twitter and Instagram to let prospective followers know a bit about you. You should aim for people to be able to quickly skim your profile and immediately get an idea of who you are (or who you’d like them to think you are). You can include details such as your job title, location and interests, but try to avoid getting too overtly self-promotional, which is just tacky. It’s fine to add a link to your website/blog/newsletter/YouTube, but limit yourself to one at a time.

When it comes to profile pictures, bear in mind that any image you upload to the internet may stick around for quite some time. When I recently searched for my own name on Google Images (don’t judge), the top results included a picture I once uploaded to Twitter that now makes me recoil from my screen with embarrassment. In it, I am wearing Google Glass.

FRIENDS AND FOLLOWERS

Your experience on social media will largely be shaped by the people you connect with, so choose wisely. There are two main types of connection across platforms: friends and followers. Friendship is mutual; you can only be friends with someone if they also want to be friends with you. Following, however, is often one-sided. You’ll never be Beyoncé’s friend (sorry), but there’s no excuse not to be her follower.

Facebook friends

In theory, your Facebook friends should be your real-life friends. In practice, you’re probably not as popular as your Facebook friend list suggests.

Facebook lets you connect with up to 5,000 people, but Robin Dunbar, a professor of evolutionary psychology at the University of Oxford, says the number of actual friends we can have is closer to 150. Dunbar came up with this number – now known appropriately as ‘Dunbar’s number’ – 25 years ago, after observing a correlation between the size of primates’ brains and the size of their social groups, which he then extrapolated to human brain size. Essentially, he argues that we don’t have the time or brain power to keep more than around 150 real friendships on the go at any one time – and he doesn’t think the internet has changed that.2

Dunbar defines a friend as someone with whom you have a meaningful relationship and regular contact (this includes family members). He describes it to me as people who would willingly do you a favour without asking for anything in return, and who would expect the same from you. ‘They won’t argue about being paid back; they’ll just assume you will,’ he says. Although he puts the average number of friends at 150, he says the figure can vary from 100 to 250; younger people and people with more extraverted personalities are likely to be towards the higher end of the spectrum.

Past that point, however, and your ‘friends’ aren’t really friends; they’re more likely to be acquaintances. They could be friends of friends, people you work with or, as in my case, all the people you met in Freshers’ Week at university and haven’t spoken to since.

Dunbar reckons that many people include some of this acquaintance layer into their Facebook friend list. ‘A few people click “yes” every time they’re asked if they want to befriend somebody,’ he says. ‘Really, all they’re doing is doing what we do in everyday life, which is bringing the acquaintance layer into the digital format.’ He puts the number of acquaintances a person can have at around 500 – strikingly close to my own Facebook friend count.

Who you decide to friend really depends on how intimate you want to keep your digital social circle. You should at least know people you try to connect with – friend requests from strangers are just creepy. If you want to keep your circle small, it’s perfectly fine to politely decline a request (although good luck explaining that to your mother). If someone declines your friend request, accept it with good grace and do not re-send the request.

FACEBOOK FRIEND BINGO

How many of these appear in your Facebook friends list?

- ● Your first crush

- ● At least one former teacher

- ● That scrawny kid from school who’s now a bodybuilder

- ● That scrawny kid from school who’s now a glamour model

- ● A one-night stand

- ● Someone you met at a festival and were convinced you’d be best friends with but haven’t seen or spoken to a single time since

- ● The creepy guy from work

- ● An extended family member you can’t quite remember how you’re related to

- ● Your mum

- ● Your mum’s friend

- ● Someone you don’t recognise because they’ve changed their name

- ● Someone you don’t recognise because they’ve had plastic surgery

- ● Someone you just don’t recognise (who actually are they?)

- ● A deactivated account

- ● Your kid niece/nephew (just joking – they’re not on here, Facebook is for old people)

Unfriending

Choosing to break off a social media friendship is much more meaningful than just not connecting with someone in the first place. It’s a clear snub. You did think they were worth connecting with, but now you don’t.

If you haven’t had contact with someone for a while, you may get away with unfriending them without them noticing, but it’s always a risk. In cases where you need to be a little more tactful, there’s another option. Similar to muting someone on messaging apps, you can ‘unfollow’ a person’s account on Facebook, which means that while they remain your friend in principal, you will no longer see their posts in your newsfeed. It’s the diplomatic way to ignore someone.

If you do decide to do a bit of a friend spring-clean, just go about it quietly. Posting one of those obnoxious ‘Just did a friend cull so congrats if you’re reading this, you made the cut’ statuses is the height of poor taste.

Twitter and Instagram followers

Unlike friending, following someone isn’t necessarily an indication that you know or even like them – hence Piers Morgan’s 6.4 million Twitter followers. Instead, you should follow anyone whose output you find interesting (even if it’s just because you want to argue with it). Follow your friends. Follow people in your industry. Follow people you find funny, interesting or intelligent. Follow parody dog accounts. Check your following list – is it mainly white men? Find some women, non-binary folk and people of colour you admire and follow them too.

Don’t get too follow-happy, though. Twitter lets you follow 5,000 accounts before it starts to restrict following numbers, but if you don’t put some effort into curating who you follow, your feed will soon become unmanageable and you’ll miss the updates you actually want to see.

There are two main approaches when it comes to Twitter and Instagram. Some people use these platforms in a personal capacity, connecting mainly with people they already know IRL. Others take great pride in amassing as many followers as possible, with dreams of becoming an #influencer.

Some do both, creating two accounts for different purposes: one for their public persona and one that they keep private and share only with actual friends. On Instagram, this second account is sometimes referred to as a ‘finsta’ (a portmanteau of ‘fake’ and ‘Instagram’) and is used to share more personal, unfiltered shots with select followers, compared to the highly curated life presented on a user’s real (‘rinsta’) account.

The following:follower ratio

As a rule, having more people follow you than you are following is an indication that you’re doing something right. Try not to let your ego get too hung up on it, though. A high follower count alone isn’t a mark of quality (see again: Piers Morgan), and the worst social media etiquette faux pas you can make is trying to increase your popularity through artificial means.

One common and slightly sleazy trick is to follow lots of people in the hope that they’ll follow back. Or worse: follow lots of people in the hope that they’ll follow back, then unfollow them when they haven’t responded, then follow them again in the hope that maybe this time they’ll follow back. While you might get away with it sometimes, it’s only a matter of time before someone calls you out. Some desperate souls don’t even try to hide their motivations, blatantly tagging pleas like #followforfollow or #followback.

Avoid this approach; we can all see what you’re doing. The only real way to get more followers is to engage with the community (or you can just buy fake followers from dodgy corners of the internet – but it’s kind of obvious when your count suddenly jumps by a nice round number).

How your following:follower ratio stacks up

| 1:1 million+ | You are Beyoncé-level famous |

| 1:100,000 | You are very famous |

| 1:10,000 | Still famous |

| 1:1,000 | You’d count as a celebrity of some kind |

| 1:100 | You’re an #influencer |

| 1:10 | You’re quite good at this |

| 1:1 | You’re a normal person |

| 10:1 | You’re still a normal person |

| 100:1 | Not many of your friends are on here, are they? |

| 1,000:1 | :( |

Verified accounts

Many social media sites offer a ‘verified badge’ to show that someone’s account is authentic. On Twitter and Instagram, this is the coveted blue tick that appears next to people’s names. The exact criteria for getting one are kept pretty murky. They’re generally reserved for public figures, so that users can tell that politicians, celebrities and so on really are who they say they are and not an impostor.

Who exactly counts as a public figure, however, appears to be relatively arbitrary. A verified badge really doesn’t confer much more to the beholder than a sense of smugness, and there’s no need to get in a tizzy over it. Certainly don’t do what WikiLeaks editor Julian Assange did when Twitter refused to verify his account and put the blue diamond emoji next to your name to try to fool people into thinking you have a blue tick. Tragic.

Likes and favourites

The minimal form of interaction you can have on most social media sites (other than lurking, of course) is ‘liking’ or ‘favouriting’. The iconic example is Facebook’s Like button, the little blue ‘thumbs-up’ sign. Twitter and Instagram, meanwhile, both have little red hearts.

A like can mean much more than just ‘I like this’. It can say ‘I agree with you,’ or ‘I think you look fit,’ or ‘I’m sorry your dog died’. Context is crucial, so if there’s any ambiguity over why you’re liking your friend’s post about their cat’s funeral, be sure to write a comment too. (Human deaths require a private message.)

For better or worse (probably worse), the number of likes a post receives has become a shorthand measure of its success. As with follower counts, try not to get too caught up on this; it’s easy to fall into the trap of constantly checking your feed after you post something, eagerly counting each little ping of validation as it comes in, but this will soon drive you to distraction.

Be generous with your own likes and gracious for those you receive. It’s vulgar to ‘chase’ likes by posting things with the explicit goal of gaining interactions. In 2017, Facebook announced it would start demoting posts it classes as ‘engagement bait’, which includes posts that goad people into interacting with a post – ‘Like if you think you’re smarter than this!’ – or that attempt to use likes and shares as a kind of voting system – ‘Like if you love cats, share if you prefer dogs!’

ALL THE THINGS A ‘LIKE’ CAN MEAN

I like this

I like you

Congratulations!

Well done!

This is funny

This is important

I am acknowledging that I have seen this

I think more people should see this

I want you to notice me

I agree with this

I don’t agree with this, but you make some good points

I don’t know what to say in response to this

I’m thinking of you

I have sympathy with you

I am expressing solidarity with you

I am your mother and it is my prerogative to like every single one of your posts

The only major platform to have something like a ‘dislike’ button is Reddit, where users can ‘downvote’ posts as well as ‘upvote’ them. The balance of everyone’s votes gives a kind of hive-mind assessment of whether the post is worth seeing or not. In 2015, Facebook also introduced a set of extra emoji ‘reactions’ to try to get around some of the ambiguity in a like. Beyond the original thumbs-up, you can now select one of five emoji icons in response to a post, labelled as ‘love’, ‘haha’, ‘wow’, ‘sad’ and ‘angry’. Go easy on that last one – as we’ve covered, emoji aren’t great at communicating nuance.

Finally, don’t like your own posts – this is a bit sad, like trying to high-five yourself. And never like someone’s breakup, even if you did think they weren’t right for each other. It’s awkward when they then get back together.

Shares and retweets

In the social media marketplace, a ‘share’ is worth more than a ‘like’. By sharing someone’s post on platforms that allow it, you’re not just giving it a little algorithmic boost but directly promoting it to your friends or followers, therefore increasing its visibility.

On Twitter, retweets, or ‘RTs’, are a particularly valuable commodity, and people with high numbers of followers have great power when it comes to bestowing their precious shares on those with a more lowly reach. There’s nothing more frustrating than seeing your witty tweet catch the eye of a Twitter celebrity, only for them to like but not retweet it. (Even worse are the people who still do the now-antiquated ‘manual’ retweet by writing ‘RT @yourusername’ and then copy-pasting the words of your tweet into their own post, thus crediting you enough to avoid accusations of plagiarism but keeping all of their followers’ sweet likes and RTs for themselves.)

There are two types of retweet: a retweet without comment and a retweet with comment, also known as a ‘quote tweet’. In the early days of Twitter, it was something of a trend for people to put ‘RTs are not endorsements’ in their bio. But let’s get this clear: a straightforward RT can only really be interpreted as an endorsement. By hitting the retweet button, you are purposefully pushing the post to a wider audience, which, without further comment, must mean you think it deserving of wider distribution. The disclaimer does nothing to negate this; if you retweet something offensive, no one is going to check your bio and say, ‘Oh but look, they say “RTs are not endorsements!” They’re off the hook!’ Instead, it just looks like a weak attempt to cover your arse if people disagree with you.

Be careful what you share, and never share links to stories you haven’t actually read. If you do want to retweet something that you don’t endorse – for example, in order to critique it – then you need to quote-tweet and add a note explaining your position.

The Ratio

Usually, a high number of interactions on social media is a good thing. If you get lots of likes and shares, that means lots of people have enjoyed your post. But comments can be another story. Comments on a post can be either positive or negative, and there’s no way to tell just by looking at the numbers. Except there is. It’s called The Ratio.

The concept of The Ratio took hold on Twitter around 2017. It’s a simple rule: if the number of replies to a tweet vastly outweighs the number of likes or shares, then said tweet must be bad, wrong and/or morally repugnant.

The logic is that, if people agree with you, they will most likely hit ‘like’ or ‘retweet’, and perhaps comment as well (as a general rule, if you leave a positive comment on a post you should also like it). If many more people feel the need to dive into debate in the comments without hitting like or retweet, the post can’t have been well received.

A prime example of The Ratio is found on a tweet posted to the verified United Airlines Twitter account in April 2017, in which CEO Oscar Munoz apologised following a viral video of a passenger being dragged off a flight. At the time of writing, Munoz’s rather unsatisfactory apology for ‘having to re-accommodate’ the customer has 59,000 replies and just 7,300 likes. In Twitter parlance, he got thoroughly ratioed.

Tagging

The most direct way to get someone’s attention on social media is to tag their username in a post or comment, which, depending on the circumstances, can be either a nice courtesy or a great irritant.

The one situation in which tagging is definitely necessary is to give credit. If you post a witty comment you didn’t come up with, a joke you didn’t devise or a picture you didn’t take, you must tag the original source. Otherwise, it’s just stealing. This is particularly important on Instagram, which, unlike Twitter and Facebook, doesn’t let you directly share other people’s posts into your main feed. Many get around this by using third-party ‘regramming’ apps or other workarounds, such as taking a screenshot. If you do this, make sure to include the original poster’s name and handle.

You should also tag someone in a caption or comment if you are addressing them directly in a post – it’s rude to talk about someone behind their back. Finally, you may wish to tag someone in a post or comment if you want to draw their attention to something. But only do this if you honestly, genuinely think they’ll be interested; your motives should be considerate, and not self-serving.

Acceptable: tagging your best friend in the comments of an Instagram picture of a cute sloth, her favourite animal.

Unacceptable: tagging someone you’ve never met in a Twitter post promoting your startup.

Particular restraint is required when tagging people in images. It used to be that people would routinely tag every face in every picture in every album they uploaded to Facebook – and boy did we upload a lot of pictures back then. Our expectations of privacy have since changed, however, and we’re now all a bit more wary about having photographic evidence of Friday night’s antics online for all our crushes, in-laws and future employers to find. You should therefore always get permission from people before tagging them in an image. In fact, always get permission before you post photos of them on the internet full stop.

Hashtags

Hashtags have several main functions. The first is to categorise posts using keywords, so that other users who are interested in the same topic can find related content more easily. Someone posting an Instagram picture of a cake they made might use the hashtag #baking, so other keen bakers can see the fruits of their labour. Someone posting a tweet about this week’s Great British Bake Off might use the hashtag #GBBO, so other viewers can see their opinion on whatever mean thing Paul Hollywood said this time. Hashtags can also unite people around more serious causes or express solidarity for a movement, such as #BlackLivesMatter or #MeToo.

Companies often try to tap into the hashtag phenomenon by inventing their own – with varying degrees of success. The problem is, once a hashtag has been cast out into the Twitter- or Instasphere, it is at the mercy of the social media masses, who don’t always have the same idea for it as the company’s marketing department intended. Notable missteps include #McDStories, which McDonalds introduced in 2012 for people to share stories about how much they loved the fast food chain, but which soon got flooded with tales of not-so-Happy Meals. Similarly, in 2014 the New York Police Department envisioned the public using its #MyNYPD hashtag to share warm-and-fuzzy photos of themselves with police officers, but it was soon hijacked by people sharing stories of police brutality instead. (At the time of writing, it mainly brings up tweets moaning about police cars apparently violating traffic rules.)

Another purpose of hashtags is to add semantic context to a post. Like emoji, a hashtag can add an emotional inflection or give the reader a clue as to how a post is meant to be read.

Time to get out of bed and head to the office

#MondayMotivation

has a very different meaning to

Time to get out of bed and head to the office

#ihatemondays

Just to confuse everyone, however, many people use hashtags ironically, so don’t necessarily take them at face value.

The main etiquette around hashtags is not to go overboard; one or two is plenty. Adding a #hashtag to #every other #word in your #post makes it #difficulttoread and looks #spammyashell. Hashtag spamming is particularly rampant on Instagram, where people have a habit of tagging zillions of vaguely relevant words in an attempt to attract more followers. This is unlikely to make you more popular, but it almost definitely will make you look desperate.

A final word of warning: if you are inventing your own hashtag, be mindful of how it parses. Never forget that mirthful day in 2012 when singer Susan Boyle celebrated her album launch with the Twitter hashtag #Susanalbumparty. It was meant to read ‘Susan album party’, but many saw four words instead of three.

WHAT TO POST ON SOCIAL MEDIA (AND WHEN TO STOP)

Now we get to the crux of social media etiquette: what to actually post.

Try this mortifying trick. Go to your Facebook profile and under ‘manage posts’ select ‘filters’. Scroll back to a date around the time you started using the site and, under ‘posted by’, select ‘you’. Unless you’ve deleted them, this should take you back to some of your earliest ever Facebook posts.

If you’re anything like me, you’ll be faced with a wall full of thoroughly cringeworthy updates from around summer 2007. This was back when Facebook still encouraged you to narrate your life in the third person, with the prompt ‘[Your Name] is …’ Cue a bunch of inane updates about your day, like ‘Victoria is eating dinner’ or ‘Victoria is waiting for the bus’ or ‘Victoria is wondering why homework has to be soooo annoying’. (Those are just made-up examples; the real ones are far too embarrassing to publish.)

You might also come across what look like private messages between you and your Facebook friends. Around this period, it was quite normal to write personal messages directly on friends’ public Facebook walls for everyone to see – a habit that soon changed. By 2012, the idea of conducting a one-on-one conversation online in public seemed so alien that rumours started going around about a ‘bug’ in the site that had publicly exposed people’s private inbox messages. Users thought they had been hacked, not realising that these were actually public wall posts all along and everyone just had a rather different idea of digital privacy back then.

Over time, norms changed. Facebook dropped the ‘is’ in status updates, and we no longer felt the need to let all of our contacts know the minutiae of whatever we happened to be doing, thinking or eating for breakfast (that’s what Instagram was invented for). Image and video posts became more common, and news-sharing on social media became a much more widespread phenomenon, bringing a new dynamic to the news feed.

Different platforms are geared towards slightly different uses. Facebook today is mainly a place to get angry about current affairs, watch cute videos and occasionally update your mother on what’s going on in your life. Twitter, with its 280-character limit, is suited to short, pithy posts and back-and-forth exchanges between users, with fast-moving debate often responsive to news cycles. Platforms such as Instagram, Snapchat and Pinterest, meanwhile, differentiate themselves by being almost exclusively image-focused.

When it comes to composing a post, Debrett’s has some pretty solid advice on the subject of ‘social tact’ which I can’t help but think is as relevant to social media as to any high-society dinner party: ‘You may be someone who disdains political correctness, but racist, sexist or homophobic remarks are unacceptable in any circumstances. You may think you are being funny but it is best to keep humour under control.’

A note on privacy

Before you do post something, take a few minutes to look over your privacy settings. No reasonable person could expect you to go through every social media site’s complete T&Cs (many contain around the same number of words as this chapter and are, I hope, much less fun to read), but you should at least check who can see what you post. On many platforms, you can choose whether to make posts public by default, or keep them visible only to people you’re connected with. It’s better to find out now than when your boss likes that beach-break selfie you posted while you were ‘off sick’.

Remember, however, that the internet doesn’t forget and, even with carefully configured privacy settings, your posts could easily end up in front of a wider audience than you anticipate. Dance like no one’s watching, sing like no one’s listening, but post online like everything you write could one day be read by your boss, your mother or a court of law.

Posting frequency

There’s a fine line between keeping your friends and followers regularly updated and spamming. Post too often and you’ll be that annoying friend who clogs up everyone else’s feeds; post too little and your mum will complain that she has no idea what’s going on in your life any more.

Exactly how often you should post corresponds roughly to how ephemeral the platform is. You should post less on platforms like Facebook, where posts can hang around in the news feed for a while, than on Twitter, where tweets soon get buried by fresher fare. By the same token, you should be more selective with the photos and videos you post on your main Instagram feed than on your Instagram or Snapchat Story, where they disappear after 24 hours.

There’s no set rule for the maximum amount you should post, but my rule of thumb is:

| 1 post per day | |

| 1 post per day (but can include multiple photos in one post) | |

| 1 post per day | |

| 10 posts per day | |

| Instagram/ Snapchat Story |

10 posts per day (but only if you have lots of interesting things to share, like if you’re on holiday) |

These are maximums. Don’t feel like you need to post if you don’t have something to share. We’re not going to call the Missing Persons Unit if your Instagram isn’t updated every day.

Image posts

Over the past decade, images have become much more important on social media, and our approach to posting photos has also evolved. The emphasis is now firmly on quality over quantity. No longer is it acceptable to upload a whole album of holiday snaps to Facebook; you need to curate that one picture-perfect shot for Instagram (because if you come back from holiday without hashtagging a #sunset, did you really go away at all?).

A-Z OF INSTAGRAM CLICHÉS

A is for aerial views of avocado toast

B is for #blessed

C is for circle of feet

D is for ‘doing it for the ’gram’

E is for eggs (and other breakfast foods)

F is for FOMO

G is for graffiti wall

H is for hand heart

I is for influencer

J is for jumping for joy!

K is for Kardashians

L is for ledge, dangerously perched on

M is for ‘mood’

N is for #nofilter

O is for ocean view

P is for plane window

Q is for (inspirational) quote

R is for Rich Kids of Instagram

S is for ‘sound on’

T is for #throwbackthursday

U is for unicorn pool inflatable

V is for vintage

W is for weddings, weddings and more weddings

X is for your ex who likes every selfie

Y is for yoga poses

Z is for zealous use of zoom-ins in your Instagram Story

Dave Burt, CEO and founder of social media agency Be Global Social, says the key to a successful account is curation. And he should know – he runs the popular @London Instagram account, which has more than 2 million followers and a billion total views. If you’re trying to attract a following, Burt advises finding your brand and sticking to it. The @London account is about celebrating London, and that’s exactly what it does, with pictures of landmarks, art and food around the city. Iconic landmarks such as Big Ben and Tower Bridge routinely perform well, but variety is also crucial. ‘If you post a picture of Tower Bridge seven days a week, people get bored of that,’ Burt says. The same goes for your selfies, bikini shots and pictures of brunch.

Put some thought into lighting and composition. Think about things like the ‘rule of thirds’ – arranging objects in your photo as if they’re in a 3x3 grid, which often produces a pleasing aesthetic. Only use filters if they actually enhance your image, not just as a gimmick. Putting your whole feed in Gingham doesn’t make you some kind of kooky artist, it just makes all your pictures look washed out.

Selfies

Selfies get a lot of flak – they’re narcissistic, they’re vain, they’re self-indulgent – but we all love them really. A paper by researchers at Georgia Tech and Yahoo Labs that looked at 1 million Instagram posts found that photos containing a face were 38 per cent more likely to be ‘liked’ than photos that didn’t, and 32 per cent more likely to attract a comment.3 And before you assume that these results may have been skewed by a few super-hot subjects posting thirst traps, know that the age and gender of the person or people in the photo didn’t affect how much people engaged with it.

This makes sense to me: I follow people on Instagram primarily because I want to see what’s going on in my friends’ personal lives, not an endless stream of latte art – and what’s more personal than a picture of yourself? Just don’t overdo it. Not every photo should be a selfie. And don’t take yourself too seriously – it’s OK to smile sometimes.

Seven selfie archetypes

If selfies are a means of self-expression, we’re not a particularly original bunch. Here are some common examples you’ll no doubt see pop up in your feed.

The thirst trap

Thirst traps are knowingly designed to be sexy as hell, with the express purpose of attracting attention – and the likes that come with it. They often feature a lot of skin, ‘duck face’ expressions and as much nipple as Instagram will let you get away with (which, to be fair, isn’t much). The gym selfie also falls into this category.

The no make-up selfie

The idea behind the no make-up selfie trend was to empower women by rebelling against unrealistic beauty standards – which might have worked better if it wasn’t mainly embraced by people who already have perfect bone structure, flawless skin and lip fillers. #iwokeuplikethis

The ugly selfie

Unlike the actually-still-very-attractive no make-up selfie, the ugly selfie is purposefully unflattering. The fatter your double chins, the goofier your teeth and the more scrunched-up your nose, the better. The ugly selfie is meant as an antidote to the perfectly posed portraits in most of your Instagram uploads.

The fashion selfie

The fashion selfie is unusual in that it’s full-length, the better to show off your #ootd (outfit of the day). This means you usually have to rope some other poor sod into taking the picture so you can prance about finding your best angles – making its status as a selfie debatable. Just make sure to carefully hide the tags on everything so you can return them for a refund once you’ve got the right shot …

The emo selfie

Before there was Instagram, there was Myspace, and though the early social media platform may have since floundered, it left behind an unmistakeable aesthetic: the emo selfie. Trademarks include the ‘Myspace angle’ (camera held aloft and to the side) and copious amounts of hairspray. Bonus points if you take it with an actual digital camera, not a phone.

The arty selfie

The arty selfie is for people who think they’re far too sophisticated for selfies yet still can’t resist the lure of the front-facing camera. Moody lighting is a must, as are a few highbrow accessories, like a stack of books carefully positioned as if they just happened to get caught in shot. What do you mean, you don’t always carry a copy of Infinite Jest around with you?

The belfie

Possibly the only selfie where your face isn’t the anatomical focus, the ‘belfie’ is a selfie in which your posterior takes pride of place (‘belfie’ referring to a ‘bum selfie’). You don’t need to be a contortionist to take one: just position yourself in front of a mirror, clench those buttocks and take the shot over your shoulder. You’re welcome.

‘Candid’ shots

Almost more common than selfies on social media these days are faux-candid shots, sometimes known as ‘plandids’ (for ‘planned candid’). This apparent oxymoron refers to pictures that are presented as if they were just snapped in the moment, but that we all know you actually spent at least 10 minutes trying to perfectly position yourself for, your boyfriend-slash-obligatory-personal-photographer taking a whole roll of pictures until he got that one where the breeze was lifting your hair just so.

Plandids usually catch the subject in a not-at-all-obviously-staged pose, like sitting on a beach in a spontaneous yoga position or staring wistfully at the horizon (don’t you just find yourself doing that all the time?). Another favourite is the ‘follow me’ pose – a picture of you from behind, with one hand stretched back towards the photographer. It’s just a totally natural and not-at-all-awkward way to hold hands.

If you’re single and too mortified to ask someone else to take 2,000 shots of you in your bikini until you get one that flatters all of your wobbly bits, then you can take a plandid with the help of your phone’s timer. Pro tip: use your camera’s burst mode. Getting that perfect ’gram is a numbers game.

Food photography

Food photography on social media was never that noticeable until Instagram came along, and something about that square-shaped frame apparently brainwashed us all into thinking we were restaurant critics. Now, it’s rare to enjoy a meal out without spotting someone with their phone floating over their plate.

The main rule of food photos is that the food itself must look appetising. Your lovingly homemade lasagne might taste great, but if it looks more like a dog’s dinner than fine dining, there’s only so much a filter can do. Take care when plating to make a composition that looks interesting. It is the law that food photos must be taken from overhead.

Breakfast and brunch foods are especially popular on Instagram, to the extent that it’s now incredibly passé to post pictures of smashed avocado or eggs on toast, no matter how deliciously oozy you’ve got the yolks. And please don’t post pictures of healthy foods, like salads or those abominable green smoothies – we want to see food porn, not sanctimonious reminders of how disgustingly healthy you are.

If you’re taking pictures of food while eating out, remember your table manners and be considerate of fellow diners. It’s acceptable to take one shot of a particularly good-looking dish, but not to spend half the evening hovering out of your chair to get that perfect aerial view.

Stories

Snapchat, Instagram and Facebook all have ‘Stories’ channels now, which are separate to your main feed and let you post a series of photos and videos that disappear after 24 hours. This means you can share extra moments from your day without clogging up people’s feeds with multiple posts.

Stories usually have a more personal, ‘behind the scenes’ feel. Think actually candid, not plandid. Stories also let you add text, stickers and animated filters to your posts. Text can be helpful to explain what’s going on in a picture, but keep it snappy. Remember that each clip in a Story only displays for 10 seconds unless you hold your finger on it, and there’s nothing more annoying than trying to race through a long description only for the next post to flash up before you reach the end. If you include video clips, avoid relying on audio, as many people browse with the sound turned off.

Oh, and shooting Story posts in landscape orientation is a social media cardinal sin.

Memes

Photos aren’t the only kind of image post. There’s another sort, and it spreads like wildfire. I’m talking, of course, about memes.

Think of a meme and the first thing to spring to mind is probably an image overlaid with some kind of amusing text, most likely in white, bold Impact font. Maybe it’s a cat asking, ‘I can has cheezburger?’ or a frustrated Boromir from Lord of the Rings wisely imparting that ‘One does not simply walk into Mordor.’ These kind of memes, known as image macros, are just the tip of the iceberg.

The word ‘meme’ was coined by evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins in his book The Selfish Gene. Dawkins explains in his book that he settled on the word as ‘a noun that conveys the idea of a unit of cultural transmission, or a unit of imitation’ (his emphasis). He was not talking specifically about digital culture; The Selfish Gene was originally published in 1976, a full 13 years before the creation of the World Wide Web, so we can safely assume that he had never come across a lolcat by that point. Rather, Dawkins wrote, memes are anything that propagates by ‘leaping from brain to brain’, such as ‘tunes, ideas, catch-phrases, clothes fashions, ways of making pots or of building arches’. It was only after the internet became commercial that people began to apply the idea of memes to digital content.

These days, memes are often associated with images, though they can be anything – videos, songs, texts, catchphrases or more nebulous behaviours. Limor Shifman, an associate professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem who has studied internet memes and published a book on her findings, Memes in Digital Culture, says that there’s a difference between a meme and something that just ‘goes viral’. A piece of content goes viral when it is seen and shared by many people. A meme, however, not only gets shared but is also adapted along the way – remade and remixed again and again to produce endless variations. This is where Dawkins’s ‘unit of imitation’ definition comes in.

To take an example: ‘Gangnam Style’, the 2012 runaway hit by South Korean artist PSY, is a viral music video; it now has over 3.2 billion views on YouTube. But what makes it a meme is the fact that people have made their own versions, imitating the dancing or creating parody videos.

Schifman says that the reason we love memes so much is because they allow us to express ourselves both as an individual and as part of a collective. ‘When I create my version of a popular video, I simultaneously convey my individuality – this is my body, my sense of humour, my talent – and some communality to a shared core,’ she explains. Memes can also help form a kind of in-group language, with specific online communities adopting memes that outsiders don’t understand, to help establish a group identity.

Some memes enjoy abrupt but short-lived popularity, while others stick around for years. The ones that last longest are often very versatile and appeal to some kind of core human sentiment. Schifman gives the example of Success Kid, an image macro that features a baby boy clenching a handful of sand in a way that makes it look like he’s doing a celebratory fist pump. This image first became a meme around 2007, with people adding text that usually centres around celebrating a minor victory. More than ten years later, it’s still going strong. ‘Success Kid is still around because this notion of being successful in trying conditions is still appealing,’ Schifman says.

And while memes are often used as jokes, they can have more serious contexts. Memes are increasingly used in politics and activism, or to raise awareness of social issues. Schifman gives the example of the #MeToo movement. ‘#MeToo is a very good example of a meme that is both personal and political,’ she says. ‘When a woman posts a Facebook post or a tweet about her own sexual harassment, she simultaneously says something personal about herself, but at the same time she pinpoints a broad political problem that relates to inequality and injustice.’

How to make a meme (if you must)

As with gifs, you can find repositories of memes online, which you can share or adapt at will. If you’re feeling creative, you can even make your own. Image macros are among the easiest to make. All you have to do is take an image, add a witty caption and voilà, you’ve made a meme. (Well, you’ve made an image macro, which, if you’re lucky, may take off as a meme.)

There are many web-based tools that do a lot of the work for you, such as Imgur’s and Imgflip’s meme generators. These sites let you choose from a selection of common meme images or upload your own, and then prompt you to enter text in a template so that it appears in the right place over the image. When you’re done, hit ‘generate meme’ and there you have it.

There are a few different types of image macro, including ‘Advice Animals’, which present an animal or personality as a kind of stock character (Boromir and Success Kid come under this category) and ‘object labelling memes’, where certain parts of the image are labelled to comic effect, as in the ‘distracted boyfriend’ or ‘expanding brain’ memes. If you have no idea what I’m talking about, the KnowYourMeme database is a great resource for translating whatever weird craze has taken hold of the internet by the time you’re reading this book. Just keep a few pointers in mind before you start sharing your own meme creations:

Know your audience. Some memes are self-explanatory, but others require prior knowledge to make any sense. Stick to the classics if you’re posting in an environment where others may not be entirely au fait with the latest meme trend. Or, of course, you can try a niche take on a common meme – though this can get boring when your feeds are filled with dozens of versions of the same image, each featuring its own in-joke.

Stick to the template. Memes rely on shared context to be understood. Mess with the template and suddenly you’ve got a Socially Awkward Penguin (a penguin on a blue background, facing left) instead of a Socially Awesome Penguin (the same penguin on a red background, facing right). Awkward.

Make sure you understand the meme. That weird-looking cartoon frog? That’s Pepe, and while he used to be known for his catchphrase ‘Feels good man’, he’s now become associated with alt-right ideology. One to avoid.

Don’t turn real people into memes. Public figures are fair game, but don’t try to turn someone you know into a meme, as it might end up haunting them. I’m sure Scumbag Steve is a lovely person really.

HOW (NOT) TO BEHAVE ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Now we’ve covered the basics, it’s time to dig our teeth into some of the more nuanced manners and problematic behaviours when it comes to digital etiquette and online communities. Because while social media can help forge connections to share wisdom and support, it can also bring out the worst in people. From minor irritants to genuine societal concerns, here are some of things you should avoid doing.

A non-exhaustive list of all the annoying people you know on social media

Everyone can count the below among their social media connections. Just make sure it’s not you.

The oversharer

Over-sharing can come in many forms. It’s the multi-paragraph feelings dump you should really be saving for your therapist, the kissy-emoji PDAs between you and your new partner and the TMI when you recount in detail your recent colonoscopy. Save it for your personal diary. We really, really don’t need to know.

Example: ‘So just got back from the doctor. Anyone got a recommendation for a good haemorrhoid cream?’

The inspirational quoter

This is the person who thinks that posting inspirational quotes and motivational messages, usually against a backdrop of a whimsical nature photo, makes them look clever or ‘deep’. These quotes usually don’t make much sense, reading more like a badly translated fortune cookie than real words of wisdom, and are often implausibly attributed to Albert Einstein or Mark Twain. Inspirational quoters may have the best of intentions, but the only thing they really inspire you to do is to punch your computer screen.

Example: ‘Every great dream begins with a dreamer’ – Albert Einstein. Soooo true, words to live by <3

The armchair activist

It’s all very well having an opinion on politics, but there’s always someone who sees everyone else’s news feeds as their own personal soapbox. They insist that they’re all about political debate but seem to have no interest in actually hearing other people’s views. They’ll often post media stories with comments like ‘This is what the media isn’t talking about,’ without a shred of irony. They constantly badger you to sign online petitions, but they wouldn’t have a clue what to do at an actual protest.

Example: ‘Sign this petition if you think saving lives is more important than watching Love Island, I guess reality TV is more important than actual reality to most people these days.’

The fitness fanatic

This is the person for whom social media is simply a place to record their sporting prowess. Whether they’re a marathon runner or a gym bunny, they treat their posts like entries in Bridget Jones’s Diary, except for instead of tracking alcohol and cigarettes they’re always going on about things like ‘PBs’ and ‘gains’. They have their Fitbit connected wirelessly so that they don’t even have to log on to show up how inadequate the rest of us are.

Example: ‘Just a gentle run this morning before work, only 20 miles today! Don’t forget to sponsor me on GoFundMe for my 17th marathon of the year!’

The consummate quizzer

Pretty much all this person posts is the results of random internet quizzes. They can tell you off the top of their head which Hogwarts house they’re in, which Disney princess they are, and which novelty ice cream flavour best represents their personality. Not content with performing this kind of BuzzFeed psychoanalysis just on themselves, they like to tag all of their friends to encourage them to take the quiz too.

Example: ‘Which kitchen utensil are you? I got: potato masher. OMG this is so accurate, I am such a masher! @Sally you should try this, I bet you’re a spatula!’

The Debbie Downer

Like a real-life Moaning Myrtle, all this person does is complain. About their job, about their relationship, about the poor customer service they received at Tesco this afternoon – the most minor thing can set them off on a public rant that sucks all the joy out of your social media feed. Reading through their posts, you’d be forgiven for thinking they’re the only person who has to deal with such inconveniences as Monday mornings, monthly bills and miserable weather.

Example: ‘Can’t believe my boss actually expects me to do work at work, it’s so unfair. Why does he get to tell me what to do anyway?’

The ‘I’m leaving social media’ prima donna

Observable evidence may point to the contrary, but it is in fact possible to stop using social media without making a big announcement about it – on social media, no less. Like thinkpieces on ‘Why I’m leaving London’ or magazine columns on ‘What happened when I gave up my smartphone for a day’, it’s not new, it’s not special, and we’re all fed up of hearing about it. It’s fine to decide not to use social media, but you don’t have to act all smug about it. It’s a personal lifestyle choice, not some great moral conundrum.

Example: ‘So, after a lot of deliberation, I’ve decided to take the difficult (but ultimately, I believe, noble) step of leaving social media. The main reason is that I think people on social media spend way too much time obsessing about themselves. In the following 2,000-word essay, I’ll explain why I’m different …’

SOCIAL MEDIA BEHAVIOURS THAT NEED TO DIE

Beyond the irritating personalities we all know and endure are some more insidious and malicious behaviours that make everyone’s online experience that bit worse.

Vaguebooking

Although initially coined in reference to Facebook posts, ‘vaguebooking’ can be observed on all social media sites. The term refers to the phenomenon whereby someone writes a post that is intentionally vague in order to get attention.

Vaguebooking posts are often emotional in nature but omit the cause of the poster’s angst, forcing their concerned friends to comment ‘What’s up hun???’ and ‘U ok???’ Vaguebookers are the kind of people who regularly use Facebook’s emoji stickers to update friends on their (usually negative) feelings. Their posts often end in an ellipsis, just in case you didn’t realise that they actually have more they want to say …

Subtweeting

Subtweeting is to Twitter what vaguebooking is to Facebook. In this case, the part of the post that remains vague is the subject. In a subtweet, the poster is clearly referring to a specific person but doesn’t directly tag their username or mention their name.

People usually subtweet when they want to criticise or mock someone but aren’t brave enough to do it to their face. It’s basically the Twitter version of bitching about someone behind their back.

Subtweeting is acceptable if you’re talking about a public figure, or if you know that mentioning the person by name would lead to a pile-on from their angry followers. In other cases, it is simply rude; if you believe you have a valid critique of someone’s behaviour, you should at least be prepared to let them respond.

Bragging, humblebragging and inspiring FOMO

Social media is made for showing off, but you should at least try to be subtle about it.

Bragging on social media can take many forms. It’s posting a zillion perfect photos of your perfect life on Instagram, or tweeting only about your own achievements. It’s using the ‘check in’ function on Facebook to let everyone know which exotic new location you’re in today, often before you’ve even left the airport. (A recent alternative to the check-in is to ask for ‘recommendations’ in a new city, framing a brag as a genuine request for help. Don’t be fooled: people who do this don’t really need your suggestions for cocktails in Rio de Janeiro; they just want you to know that they are having cocktails in Rio de Janeiro.)

Worse than straight-up bragging, however, is humblebragging – the art of bragging while pretending to do the opposite. A humblebrag is an ostensibly self-deprecating post that is in fact clearly just a front for showing off how great you are and how amazing your life is. Humblebrags can come in text or picture form and often have an air of ‘first world problem’ about them – you’re just too successful, too wealthy, too skinny, too smart.

‘OMG I’m so clumsy, I just tripped on my way onstage to collect an award!’ says the humblebragger. ‘LOL just spilled coffee on my new Chanel dress – and it was so hard to find one in a size zero!’ they complain. ‘Ugh, jet lag sucks,’ they comment on an Instagram picture of them lazing on a pristine beach in Bora Bora. And yes, it still counts as bragging if you put #blessed at the end.

All of this boasting contributes to the feeling of FOMO, or ‘fear of missing out’ – the assumption we all make that everyone else is living a much more interesting, exciting life than we are, because all we see are their carefully curated social media posts. Just remember that, in reality, they probably have just as many lonely evenings, disappointing meals and bad hair days as you do. Probably.

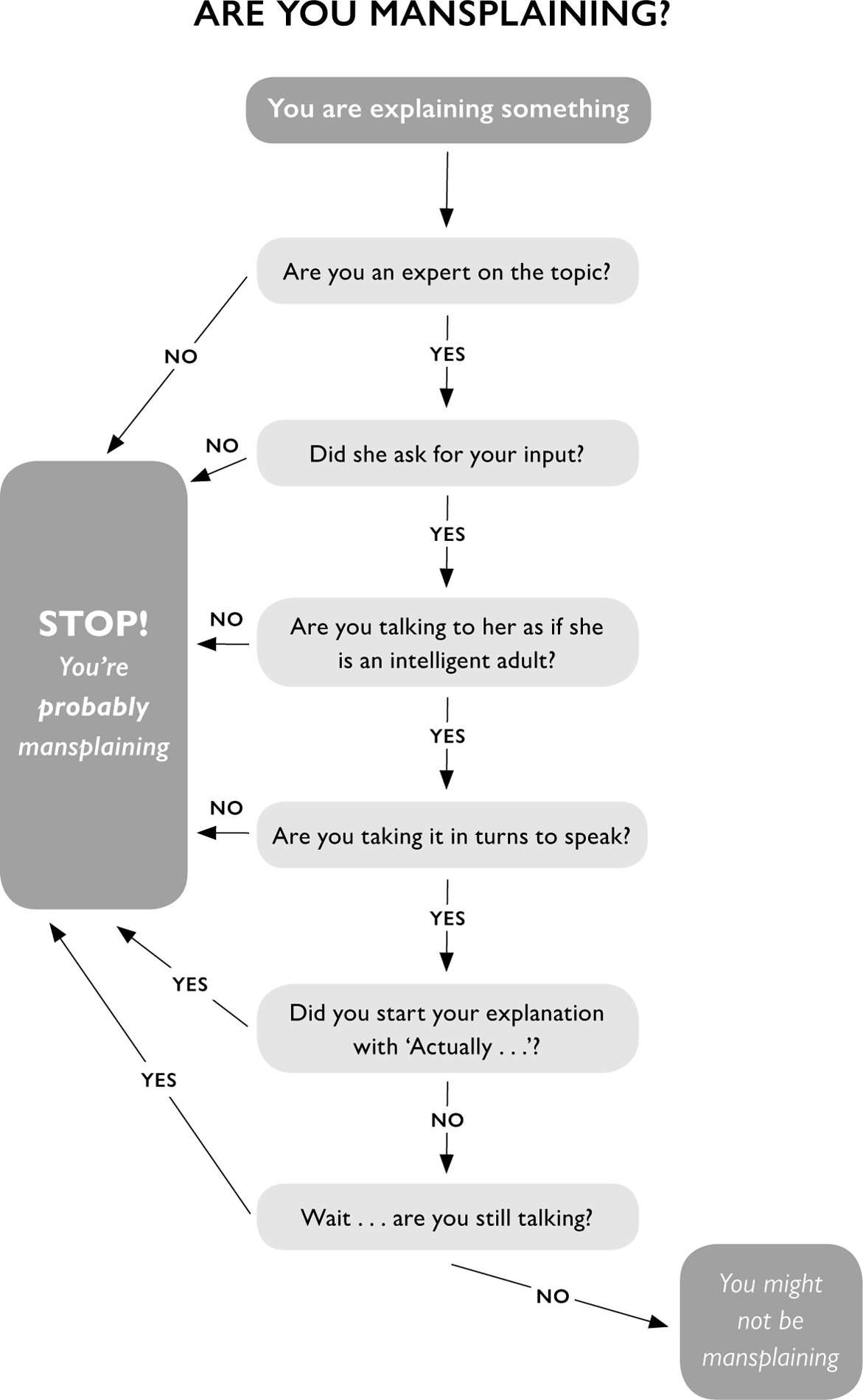

Mansplaining

Ah, mansplaining. As if it didn’t happen enough in real life, mansplaining has truly found its spiritual home in online communities of every variety.

Mansplaining is when someone (usually a man) explains something to someone else (usually a woman) in a patronising manner that insults their intelligence. The phenomenon is epitomised in Rebecca Solnit’s 2008 essay Men Explain Things to Me, which opens with the author recounting the time a man at a party tried to explain one of her own books to her. Solnit didn’t actually coin the term ‘mansplaining’, but the word soon caught on to describe a practice that resonated with many women.

It’s important to clarify that mansplaining is not just a man explaining something. Mansplaining is necessarily condescending, based on the mansplainer’s assumption that the person they are talking to can’t possibly be as clever or knowledgeable as they are – even when all the evidence suggests as much. Mansplaining is a dude who once read A Brief History of Time trying to explain black holes to an astrophysicist, or someone who watched last night’s Masterchef outlining the finer points of chocolate tempering to a professional pastry chef. Some men are true masters of the form, nobly and selflessly taking it upon themselves to mansplain to women on such topics as feminism or childbirth. And who said chivalry was dead?

Tweetstorming

Speaking of mansplaining … Twitter threads, also known as tweetstorms, are when you write multiple tweets on the same subject in rapid succession and ‘thread’ them together by replying each time to the tweet before, so that you end up with a chain of connected posts. Threads are a way of getting around Twitter’s 280-character limit. More often than not, they’re also just incredibly obnoxious. And I’d bet my last Rolo that the Venn diagram between habitual mansplainers and tweetstormers is essentially a circle.

By posting a long Twitter thread, you’re basically asserting your dominance over your followers by insisting on taking up more than the usual allotted space. Everyone else gets 280 characters, but what you have to say is worth ten times that. In an article for tech site Gizmodo, writer Alana Hope Levinson compares tweetstorming to ‘manspreading’ – when men sit on public transport with their legs spread wide open, taking up their own designated leg room plus that of their neighbours. She invents the term ‘manthreading’ and describes those who embark on lengthy Twitter threads as ‘people who want their ideas to take up the absolute most space possible. Like Manspreading, but of digital space.’4

It’s not that people who write Twitter threads don’t occasionally have something interesting to say; it’s that they’re forcing it into an inappropriate medium. If you want to write an essay, why choose a platform that only lets you post a sentence at a time? Levinson suggests that manthreaders are particularly attracted to Twitter threads because it gives the illusion that they’re coming up with each point on the spur of the moment, firing off zinger after zinger as if they haven’t painstakingly prepared the whole thread in advance (spoiler: they have). ‘They want constant kudos for each point, a stream of high fives for each of their killer “owns”,’ she writes.

Don’t be that guy. If you can’t quite fit everything you want to say in a tweet, then a two- or three-part thread is fine, but more than that and you should probably just save it for that imaginary TED Talk you’re clearly dying to give.

FIVE SIGNS YOUR TWITTER THREAD

IS TOO LONG:

- ● You have the whole thing written out in a Word doc before you start tweeting

- ● You have to number the entries so people don’t lose track

- ● You feel the need to preface the thread with ‘THREAD’

- ● You provide footnotes

- ● You mention ‘game theory’ at any point

Public shaming

Some people just revel in others’ misfortune. Public shaming is when a person publicly calls out someone else’s behaviour in order to humiliate them, usually with the goal of damaging their career or reputation.

The canonical example of public shaming is the case of Justine Sacco. In 2013, Sacco, a communications executive, was on her way to South Africa. Before she boarded the plane, she tweeted, ‘Going to Africa. Hope I don’t get AIDS. Just kidding. I’m white!’ The tweet soon spread past Sacco’s handful of followers to become a trending topic on Twitter. Scores of strangers began calling for her to be fired, using the #HasJustineLandedYet hashtag (Sacco had turned her phone off for the flight). She lost her job as a result.

While it’s acceptable – even laudable – to call out discrimination, be wary of revelling in this kind of online schadenfreude without knowing all the facts. Social media posts can easily be taken out of context, and the snap judgement of the digital masses means reactions can soon snowball out of proportion. In Sacco’s case, the tweet was apparently meant as a joke – an ironic take on what an ignorant racist might say. It was a bad joke, but surely not bad enough to warrant quite that level of ensuing vitriol.

These days, public shaming has become a kind of rite of passage for anyone who gains some kind of public attention. Sometimes, this is justified: the public has a right to know if a newly appointed politician, for example, has a history of espousing racist or homophobic views. But sometimes, public shaming appears to be little more than a weapon of harassment, designed to bully someone into silence rather than to genuinely critique their behaviour.

Milkshake Duck

Related to public shaming, a ‘Milkshake Duck’ describes someone who suddenly enters the public eye and becomes immediately well-loved on social media, before falling out of favour just as quickly after unsavoury details about them are uncovered. The term was coined by comedy Twitter account @pixelatedboat, which tweeted in 2016: ‘The whole internet loves Milkshake Duck, a lovely duck that drinks milkshakes! *5 seconds later* We regret to inform you the duck is racist’.

A good example of a real-life Milkshake Duck is Ken Bone, the ‘undecided voter’ who won hearts with his woolly red jumper and neighbourly demeanour when he asked a question during one of the 2016 televised US presidential debates. Bone became a social media darling overnight, only to get Milkshake Ducked a short while after, when people found questionable content in his Reddit history.

IRL eavesdropping

If shaming people for their online behaviour weren’t intrusive enough, it’s become a kind of meme in recent years to eavesdrop on strangers’ conversations and then broadcast them on social media for people to laugh at, such as live-tweeting someone’s awkward first date or messy breakup. It usually starts something like: ‘Wow so the couple in the next apartment is having the craziest breakup fight right now. THREAD!’

This is highly invasive, very creepy and shows a severe lack of both online and offline manners – not to mention that you likely have no idea what’s really going on in people’s lives. In September 2018, a video made the rounds on the internet of a man shaving his beard on a train out of New York. People readily mocked him, only for him to come forward and explain that he’d just left a homeless shelter and was trying to clean up to visit his family. Have some compassion, and don’t stick your phone into other people’s business.

Fake news, and how to spot it

If you want evidence that behaviour in the digital world can have an impact beyond the world behind our computer screens, look no further than the scourge of fake news.

News-sharing has become very prevalent on social media. Scroll through your news feeds today and you’ll likely see just as many links to stories from media outlets as you will personal updates. The most recent Digital News Report by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford, published in 2018, found that 39 per cent of people in the UK had used social media as a news source in the preceding week. Facebook was by far the largest contributor, with 27 per cent saying they had used it as a news source in the past week.5

Social media’s role as a news source has been linked to the spread of fake news, with Facebook in particular coming in for criticism after it was uncovered that accounts linked to Russia had attempted to use the platform to influence US voters ahead of the 2016 presidential election.

What counts as fake news? The term has taken on something of a life of its own, being bandied around these days to mean anything from allegations of media bias to whatever Donald Trump doesn’t like. In reality, neither of these is strictly fake news. For something to be fake news, it has to be:

a) News – it must be presented as fact.

b) Fake – as in, the information must be demonstrably not true.

Opinions don’t count, however strongly you disagree with them, and there’s a difference between something being poorly conceived and factually incorrect.

Fake news is not an honest mistake; it is deliberately designed to mislead, usually to support a political agenda or for financial gain. In the most extreme cases, it can involve full-on conspiracy theories, fabricated wholesale. In 2016, a conspiracy theory known as ‘pizzagate’ went viral, which alleged that individuals close to the Hillary Clinton presidential campaign were involved in a child abuse ring that operated out of a pizza restaurant in Washington, DC (the evidence included such convincing proof as ‘maybe “cheese pizza” is a code word for “child pornography”’). The absurdity of the conspiracy might have been laughable, if it weren’t for the fact that people actually believed it and hounded the restaurant staff with threats of violence and death. Eventually, one man decided to check it out for himself – armed with an assault rifle. Luckily, in that case no one was hurt.

Not all fake news is so obvious, and these stories are purposely designed to appeal to specific biases or worldviews, which makes them highly share-able. Before you get lured into spreading something that may be fake news, stop and ask yourself these six questions:

1. Have you read the story?

It’s too easy to share a compelling-sounding story without actually reading it, but a headline emphasises the most attention-grabbing aspect and may not accurately reflect the full contents. Check that the evidence in the piece backs it up.

2. Where is it published?

If you don’t know the publication, take a closer look. Are the writing and design up to the standard you’d expect? Does the journalist have a professional profile on social media? Check the site’s mission to see if it is affiliated with a particular person, movement or viewpoint that might affect its perspective.

3. Do the sources check out?

A good journalist will always make it clear where they have got their information. Do some research on the sources quoted – are they legitimate authorities on the subject? Click on any links offered as evidence to see if they really do support the story.

4. Is it just a bit too amazing/surprising/outrageous?

Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, so anything that feels a bit too much should set your spidey sense tingling. Fake news is often designed to outrage, so be extra conscientious if something has got your blood boiling.

5. What do the fact-checkers say?

Sites like Snopes and factcheck.org regularly debunk fake news and conspiracy theories. Check if this story is a known hoax. If it’s a bombshell of a story and no mainstream outlets are running it, that’s usually a sign that it doesn’t meet general reporting standards.

6. Is it satire?

Finally, don’t be that person who accidentally shares an article by satire sites such as The Onion or The Daily Mash thinking it’s real. (And if you do, don’t pretend you were ‘just seeing if any of my friends would fall for it lol’. We all see you.)

If you do accidentally share a story you later learn is fake, don’t leave it up, as this may only cause it to propagate further. Your best option is transparency. Delete the post, and let any friends or followers know that you have removed it after learning it was not true.

Fake images

There’s a popular retort on internet forums when someone makes an improbable claim: ‘Pics or it didn’t happen.’ But photographic evidence isn’t always foolproof.

Every time there’s a hurricane or other extreme weather event, a familiar image starts doing the rounds: a shark, casually swimming down a flooded highway road. The image is completely fake. The picture of the shark was originally captured by conservation photographer Thomas P. Peschak in 2003, during a trip to South Africa with scientists from the White Shark Trust. But Peschak’s photo is very different to the ‘shark on a highway’ version; in the original, the shark is shown in stunning blue ocean following a kayaker, not swimming alongside cars in muddy floodwater. The latter is a work of pure imagination (and Photoshop).

If an image seems unlikely to be real, you can try doing a reverse image search using Google or TinEye to see if the picture has appeared elsewhere previously. Be particularly wary in the aftermath of natural disasters or terrorist incidents, which tend to attract hoaxes. One particularly heinous trend has seen trolls post fake images of people they claim are missing following school shootings and other attacks.

As AI technology advances, even videos aren’t necessarily all they seem, with synthesised videos – known as ‘deepfakes’ – superimposing one image onto another to mislead the viewer, for example making it look as if someone is saying or doing something they are not.

Filter bubbles and echo chambers

Fake news isn’t the only perceived threat social media presents to our understanding of the world. The idea of the ‘filter bubble’ refers to the fact that what we see online – including what appears in our search results and social media feeds – is influenced by algorithms that personalise the information they serve us based on what they think we want to see. This has led to concerns that our experience on social media is an ‘echo chamber’ – i.e. that we only see posts we are likely to agree with and are therefore not exposed to other points of view.

The filter bubble is often evoked in reference to political events such as the election of Donald Trump and the outcome of the UK’s EU referendum, to explain why so many people felt taken by surprise at these results. How could so many people vote for Brexit when everyone in my Facebook feed was against it?

It’s certainly true that social media sites mediate what we see and how we see it, and that there’s a concerning lack of transparency around how their algorithms work. But it’s hard to judge to what extent these algorithms cause a filter bubble or echo chamber effect beyond what we would experience regardless. The biggest effect on your newsfeed is likely to be down to the people you connect with, who, as in the offline world, are probably likely to share similar views to you anyway.

William Dutton, professor emeritus at the University of Southern California, thinks that fears around social media echo chambers are overhyped, and argues that social media can actually expose us to a more diverse range of opinions. ‘Certainly it’s very clear in my case that my Facebook friends are far more heterogeneous than my friends in real life, in my neighbourhood or in my workplace,’ he says.

The best way to counter your echo chamber, Dutton says, is to be aware of the issue. Make sure you’re getting your news from multiple sources; if you’re interested in a story you see on social media, search for information on it elsewhere, too. Don’t cull your social networks of people who have different views, but instead try to engage with their opinions. ‘Celebrate the fact that you know people and are open-minded to multiple points of view,’ he says.

TROLLING

While the behaviours we’ve covered up to here could feasibly stem from good intentions, trolling is committed with the express purpose of causing disruption.

The term ‘trolling’ has come to describe a broad range of behaviours, from your mate Rickrolling you to armies of bots waging targeted campaigns of harassment. Lucas Dixon is chief research scientist at Google’s Jigsaw, which is developing AI tools to help detect and moderate toxic comments on internet forums. He says a definition is hard to pinpoint. ‘Usually, trolling has some element of repeated behaviour; it’s not a one-off,’ he says. ‘But apart from that, there’s not much else that nails this term down.’

Trolls usually aim to disrupt a conversation, cause conflict or provoke an emotional reaction. Indeed, when you think of the origin of the term ‘trolling’, you might think of the folkloric monster that hides under bridges and causes mischief, but, while the analogy may be quite apt, some suggest that the word actually comes from a fishing technique. When you ‘troll’ for fish, you bait a line and draw it through the water, waiting for them to bite – just like the internet troll dropping an incendiary remark and waiting for someone to rise to the bait.

Trolls can have different motives. They may want to cause actual distress, they may want to make a political point, they may want to waste your time, or they may just be doing it for the lulz (for a laugh).

COMMON TROLL SPECIES

Given that the word ‘trolling’ can refer to many different behaviours, here are some of the more common types you might come across.

The prankster

The prankster trolls for a laugh – although his sense of humour may differ substantially from that of polite society. Common online pranks include bait-and-switch tricks, where the troll dupes the viewer into clicking a joke link (as in Rickrolling); advice trolling, where the troll offers to help someone but then gives them false advice for their own amusement; and old-fashioned practical jokes, which are often captured for posterity on YouTube.

The hacktivist

Some groups use trolling as a means to make a political point – for example, to raise awareness about an issue, produce satirical content or launch politically motivated online attacks. A well-known example is Anonymous, which has employed trolling antics against targets including ISIS and the Church of Scientology.

The concern troll

The concern troll pretends to align themselves with one side of a debate when in reality they hold the opposing view. They use their position as an infiltrator to voice false ‘concerns’ in an attempt to derail and undermine discussion. For example, a concern troll might pose as a feminist but then raise concerns about the way a feminist campaign is being conducted. One of the concern troll’s favourite tactics is ‘tone policing’, or trying to detract from an argument by attacking the way it is delivered instead of the actual message.

The sea lion

A sea lion is a troll who continually asks questions or demands evidence for something in order to stifle discussion (think of a toddler going, ‘But why? But why? But why?’). Sea-lioning can be particularly pernicious, as it’s often hard to tell if someone is genuinely trying to learn or is just wasting your time. When you have finally had enough, the sea lion plays the victim, perhaps trying to justify their behaviour as ‘just asking questions’ – a phenomenon that Urban Dictionary delightfully defines as ‘JAQing off’.

The harasser

Nowadays, the term ‘trolling’ is colloquially used to describe all manner of online harassment. This can include orchestrated campaigns against people (usually women and minorities) who have different opinions on the most important topics, such as human rights or video games. Tactics include pile-ons of nasty comments, threats of violence and doxing, which means revealing private or identifying information about a person, such as their address or phone number. In some cases, there is little boundary between online and offline harassment.

The troll farm

Trolls at troll farms aren’t individual keyboard warriors trying to provoke a response for their own gain; they are employed in groups to produce ‘troll’ content such as fake news, in a bid to influence political events. A Russian state-backed troll farm called the Internet Research Agency was found to be behind thousands of social media accounts that spread propaganda in the lead-up to the 2016 US elections.

There’s no easy solution to dealing with trolls. The old wisdom of ‘don’t feed the trolls’ might work sometimes, but it can also play into harassers’ hands by denying their victims a voice. You can block someone or report their account if they overstep a platform or forum’s rules – take a screenshot as evidence first – and in cases of actual harassment, it may be appropriate to report it to the police.

Personal attacks, or how to quell your inner troll

There’s a common assumption that most online abuse is committed by a small but vocal minority of trolls intent on ruining the internet for everyone else, but Lucas Dixon says that’s not always the case. In one study, his team looked at people who made personal attacks within the Wikipedia community.6 ‘We found that, while there are a small number of people who contribute a disproportionately high fraction of the personal attacks on Wikipedia, most personal attacks are not by them,’ he says.

In short: it’s not just trolls that troll. Dixon calls this the ‘bad day hypothesis’ – the idea that anyone can have a bad day and then take it out on someone online. Jigsaw is currently working on a tool that aims to predict when a conversation is about to go sour by analysing language patterns, and to advise you to reconsider your contribution before hitting ‘send’.

In the meantime, Dixon advises taking a step back to reflect when you feel your inner troll rising. The most obvious sign that a conversation is turning bad, he says, is when someone makes an ad hominem attack, which means criticising a person’s character instead of their argument. He also warns against assuming ill intent on the part of the other person – which includes accusing them of being a troll who’s just trying to derail the conversation. ‘That may or may not be true, but if you say it, you’re going to be helping to derail the conversation,’ he points out.

When to leave an argument online

Exercising self-restraint when someone is Wrong On The Internet is a unique emotional struggle, but if any of the following happen, it’s time to cut your losses.

- ● Someone compares something to Hitler or the Nazis (also known as Godwin’s Law)

- ● Someone is anti-Semitic

- ● A straw man appears

- ● ‘I’m not racist, but …’

- ● Someone purposely mis-genders someone