CHAPTER THREE

Ex nihilo, ex plenitudo

The All-Transcendent, utterly void of multiplicity, is Unity’s Self, independent of all else … It is the great beginning, wholly and truly one. All life belongs to it.

—Plotinus

Both the first book of the Old Testament of the Christian Bible, as well as the most mystical of the canonical Gospels of the New Testament, The Gospel of John, begin their cosmogonies, quite logically it would seem, in the beginning: “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth” (Genesis 1:1, King James Version [KJV]), and, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. The same was in the beginning with God” (John 1:1–2, KJV). On the other hand, Gnostic cosmogonies typically begin with an eternal realm before the beginning or, more accurately, outside of time altogether. For example, The Secret Book of John (a.k.a. The Apocryphon of John) of the Nag Nammadi Library teaches that the ineffable ultimate mystery, the One, is illimitable, unfathomable, immeasurable, invisible, unutterable, and unnameable, since nothing existed before it in order to limit it, fathom it, measure it, and so on. It is eternal since it is beyond time. Rather than being considered God, or a god, or even being likened to a god, the One should be thought of as being greater than a god, with nothing over it and nothing preceding it. Similarly, the text Eugnostos the Blessed teaches that the ultimate divinity should be addressed as Forefather rather than Father. The Father is the beginning of the universe but the Lord is the Forefather without a beginning (Meyer, 2007).

The Dominican theologian, and perhaps Christianity’s greatest mystic, Meister Eckhart (1260–1327), proposed that, whereas theologians might argue, the mystics of the world spoke the same language. In the following description of the ineffable One, Eckhart is certainly speaking the same language as the Gnostic mystics:

But the perfect reflection of the One is shining by itself in lonely silence, there safely pent as one and indivisible. The unity (of God) is un-necessitous, it has no need of speech, but subsists alone in unbroken silence. … O unfathomable void, bottomless to creatures and to thine own self, in thy depth art thou exalted in thy impar-tible, imperishable actuality; in the height of thy essential power thou art so deep thou dost engulf thy simple ground which is there concealed from all that thou are not.

(Meister Eckhart)

For the Gnostics, not only is the One beyond time, in other words, non-temporal, the One is also non-spatial. The Teachings of Silvanus informs us that it is incorrect to conceive of God as being in a place as this would localise God thus exalting the place over the one who exists there given that the container is deemed to be superior to that which is contained. Echoing the ancient Greek philosopher Empedocles (c. 490–c. 430 BCE)—who subscribed to a monist perspective and likened the nature of God to a circle of which the centre is everywhere and the circumference is nowhere (Figure 3)—Silvanus taught that the One was simultaneously in every place, but also in no place, insofar as the power of the One is everywhere but the essence of the One’s divinity cannot be limited to any one place because nothing can contain it. For the ancient Gnostics, the One was a transcendent, ineffable mystery beyond both time and space.

* * *

There is no single Gnostic creation myth, although the creation myth in The Secret Book of John might be considered by some to be the de facto standard. Rather, Gnostic creation myths are varied and, more often than not, convoluted to a seemingly excessive degree. Often they tend to obfuscate rather than illuminate. Therefore, the simplified description presented here is a general synthesis, drawn from a number of creation myths in the Nag Hammadi Library. Hopefully, it highlights the salient features of Gnostic cosmogony without getting mired in the often unintelligible details.

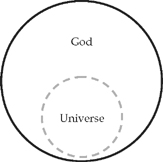

Gnostic creation myths can typically be categorised as forms of monism. In other words, they conform to the metaphysical doctrine that conceives reality as a unified whole founded on a single, indivisible, and eternal entity known as the monad. In Gnostic cosmogony, the monad is considered to be wholly transcendent, ineffable, immaculate, incorruptible, and, from the point of view of the human mind, unknowable. It is completely alien to the created world (Figure 4). The various Gnostic schools referred to this monad differently. For example, the Sethians referred to it as the Great Invisible Spirit, whereas others, such as the followers of the Gnostic teacher Basilides, referred to it as the Pleroma. This ultimate divinity is better conceived of as non-being, rather than a being, as it is beyond being itself. It is a God-above-God, and more akin to the Godhead of Meister Eckhart’s metaphysics, rather than God. It reposes in peace, outside of time in the unfathomable depths of silence.

In mainstream Christian theology, the doctrine of creation maintains that God, through an act of will, created the universe ex nihilo (out of nothing) and, as such, creator and creation are separate. In contrast, Gnostic cosmogony is emanationist in that it sees the universe as coming into being through a process of emanation out of the fullness (ex plenitudo) of the Great Invisible Spirit. The entire created realm, or universe, came into being from this primal unity through a process of successive emanations of male/female binary opposites with each pair, taken together, forming what is termed a syzygy. Out of the nothingness of the Great Invisible Spirit, came the fullness of the paired opposites. These emanated beings, or powers, are referred to by the Gnostics as aeons, and together they constitute the fullness of the Great Invisible Spirit in a way that is not unlike the way Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious is comprised of the archetypes. The last of these aeons is Sophia, Holy Wisdom, who, in Christianised forms of Gnosticism, forms a syzygy with her consort, Jesus Christ. Contemporary Gnostic priest, Jordan Stratford (2007), likens this process of emanation to a stone dropped into a still body of water. The peak and trough of the waveform initiated by the first splash of the stone represented the primordial and eternal binary opposites, emptiness/ fullness, potential/actual, male/female, yin/yang, and so on. As each succeeding pair became further removed from the original perfection they became increasingly more material with the transition from the immaterial realm of light to the material realm resulting from an error, rooted in ignorance, which led to a disruption of the aeonic harmony in the Pleroma. This creation-as-error is a principal theme of Gnostic cosmogony. For example, The Gospel of Philip states emphatically that the world came into being through error. This error is typically attributed to Sophia who, feeling estranged from the primal unity, sought to emulate the Great Invisible Spirit. In an act of passion she attempted to emanate out of herself. However, she did so without the approval of the Spirit and without the consent of her consort, and the result was an imperfect and deformed bastard offspring called Yaldabaoth who is known as the demiurge (or “creator”, derived from a Greek word that originally meant “craftsman” or “artisan”). The demiurge is described as the ignorant darkness, and in symbolism he is typically represented as having the head of a lion and the body of a snake, or a dragon, and eyes that flash lightning bolts (Figure 5).

Subsequently, the demiurge, in collusion with his underlings, the archons, created, through an act of ignorance, the material world, and then the first human. First, the demiurge attempted to fashion a world in the “indestructible pattern” of the first aeons of the Pleroma. However, he is a blind (ignorant) god and therefore cannot actually see the indestructible realm, he can only perceive it dimly due to the power he received from his mother. Consequently, the created world is a counterfeit world fashioned by the counterfeit spirit of the demiurge and his archons. Once complete, the demiurge surveys his creation and declares to his archons that he is God, and, like the God of the Old Testament, he is a jealous God claiming there to be no other gods but him. Of course in stating this—as The Secret Book of John points out—he thereby admits that there must, indeed, be another God, otherwise of whom could he possibly be jealous? Second, the archons, under the direction of the demiurge, created the first human. However, the human they created was a psychic and material body only, and lacked the spirit of light to animate it. Having seen the work of the demiurge and his archons, Sophia now repented at what she had instigated and prayed for forgiveness. Answering her prayer, the Great Invisible Spirit outwitted the ignorant demiurge into blowing the spirit that the demi-urge had received from his mother, Sophia, into the first human. As a result, the light left the demiurge and entered the first human bringing him to life. Realising that the first human contained the light that they lacked, the archons became jealous and cast him down into the lowest reaches of the material world where, according to the Gnostics, he remains a prisoner.

Figure 5. A lion-faced deity thought to represent the demiurge.

The Gnostic schools of antiquity flourished in the city of Alexandria in Egypt, and the Egyptian religion no doubt provided an inspiration, if not the direct source, for the Gnostic creation myths. The most ancient creation myth of the Egyptians is that of Atum (Ellis, 2012). First, there was nothing, and out of the nothingness, Atum came into being because becoming is his nature. Like the Great Invisible Spirit of the Gnostics, Atum is considered to be the absolute reality, and is described as immaculate, incorruptible, and so on. He is considered to be the God of the beginning and the end, and, as such, is outside of time. Everything emanated out of Atum, and, at the end of time, everything will return to Atum (ibid.). “I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the ending, saith the Lord” (Book of Revelation 1:8, KJV) immediately comes to mind. Atum begins creation by bringing forth twins. He sneezes out Shu, the god of dry wind, and spits out Tefnut, the goddess of moisture (ibid.), and the whole of creation proceeds from this first pair. (It sounds like we are nothing more than the by-product of some gooey stuff that flew out of God’s nose.) Next come the goddess Nut, the water of Heaven, and her husband-brother Geb, the god of Earth. Thus, as for the Gnostics, creation proceeds as the emanation of male/female syzygies out of a primal nothingness.

The key principle of Gnostic cosmogony is not so much the idea of creation-as-error, but the idea that inherent in the process of the creation of the material world is a profound disruption to divine harmony. When Sophia decided to create on her own without the consent of her partner it resulted in a rupture to the balance of the primal syzygy, which, in turn, led to the birth of the demiurge, the archons, and the created world. If the primal syzygy had remained in perfect balance, unity would have persisted and the manifest universe could not possibly have come into being. This world required the harmonious balance to be disturbed and, as a result, disorder is not merely an unfortunate by-product of creation but, in the Gnostic tradition, one of the fundamental principles on which it is founded.

***

And what, Socrates, is the food of the soul? Surely, I said, knowledge [gnosis] is the food of the soul.

—Plato

Gnosis (derived from the Greek word gnosis meaning “knowledge”) refers to direct, unmediated, experience of the divine, as opposed to knowledge, in the sense of information—typically someone else’s— about the divine. It is not unique to the Gnostic tradition. In one form or another, it is the sine qua non of all forms of mysticism; other traditions simply refer to it by other names. However, as the name suggests, it is indispensable to the Gnostic worldview, and its attainment considered essential to achieving salvation and the ultimate goal of Gnostic systems which is to return to the Pleroma. To have experienced gnosis would be to have had a mystical experience through which one has grown spiritually, and to have attained, or acquired, gnosis would be to have completed spiritual development, a state which is, more or less, the direct correlation of having attained enlightenment in Eastern systems. In other words, gnosis accrues incrementally through mystical experience, and one can be described as having attained full gnosis upon reaching complete spiritual awareness. As gnosis is seen as essential for humanity’s salvation, then its corollary holds that—as is claimed, for example, in the Authoritative Discourse of the Nag Hammadi Library—ignorance is the worst sin. Thus, the Gnostic tradition shares the view with Buddhism that enlightening wisdom is salvific, and ignorance, considered to be one of the three “poisons” in Buddhism, is antithetical to salvation. Similarly Jung believed that humanity’s worst sin was unconsciousness and that knowledge of the truth of the human condition was essential for psycho-spiritual growth and ultimate salvation. So too did PKD realise the need for gnosis. Indeed, he claimed that the gnosis which the Gnostics sought was the only road to our salvation (2001, p. 265).

***

Like most Gnostic creation myths, Jung’s Gnostic vision, articulated in the Seven Sermons, begins with nothingness. Paradoxically, this nothingness is also the fullness. The nothingness is, simultaneously, both empty and full. Like some of the ancient Gnostics before him, Jung referred to this nothingness/fullness as the Pleroma. Danish Nobel Prize-winning quantum physicist, Niels Bohr (1885–1962), is reputed to have stated that the opposite of a fact is a falsehood, whereas the opposite of one profound truth may be another profound truth. In a similar vein, it would appear that, whereas in the mundane, everyday world of so-called reality, paradox does not make any sense, in the ineffable realms paradox, according to the Gnostics—and possibly Bohr, if some kind of parallel can be drawn between the ineffable and the quantum realms—is a fundamental principle. Thus, in keeping with the paradoxical nature of the ineffable, the Pleroma is, simultaneously, both the fullness and the emptiness. (It is worth noting in passing that, such was the importance of duality as a fundamental law of reality to Bohr, that when a Danish knighthood was conferred on him, he designed his own coat of arms to include the Taoist yin-yang symbol (Rosenblum & Kuttner, 2012). As will be discussed below, duality, or the theme of the opposites, is the very crux of Gnostic metaphysics.)

The nothingness/fullness of Gnostic cosmology might be usefully described as mitigated apophatic theology. Apophatic theology is a theological stance that considers the ultimate divinity to be ineffable to such a degree that the only way we can speak of it is by way of negation. This is in contrast to cataphatic theology which attempts to define the divine in terms of what it is—an approach which the adherents of the apophatic perspective reject as they see it as an attempt to limit the illimitable. As noted above, The Secret Book of John alludes to the Great Invisible Spirit, rather than defining it, by describing it as illimitable, unfathomable, immeasurable, etcetera. Jung’s Pleroma is apophatic in its nothingness yet, in containing the fullness within itself, its apophatism is mitigated. It has no qualities, yet it contains all qualities in a state of potential. Jung’s Gnostic view of the Pleroma shows up in his “Psychological Commentary on ‘The Tibetan Book of the Great Liberation’” (1954). Commenting on the Eastern concept of One Mind, which is a direct correlate of both the Pleroma and the collective unconscious, he states that it is without characteristics. It cannot be said to be created, or non-created, as these designations would be characteristics. Indeed, no assertions can be made about it at all since it is “indistinct, void of characteristics and, moreover, ‘unknowable’” (p. 133).

However, there is one fundamental point of departure between Jung’s concept of the Pleroma and the Great Invisible Spirit of the Gnostics. For the Gnostics, the ultimate divinity is completely alien and a wholly transcendent God-above-God; Jung’s Pleroma is simultaneously, and paradoxically (again), fully transcendent yet fully immanent. Whereas Jung inherits the Gnostic view that the created world is estranged from its source in the ineffable realm, his concept of the Pleroma remains intimately related to the created world. In much the same way that light pervades the atmosphere, and electromagnetic radiation penetrates solid objects, Jung’s Pleroma interpenetrates the created world. For the Gnostics, the Great Invisible Spirit is, in a spatio-temporal sense, distant from creation. For Jung, this spatio-temporal separation has been collapsed and the Pleroma pervades creation. This is in accord with the maybe not-quite-Gnostic Gospel of Thomas which teaches that splitting a piece of wood, or lifting up a stone, and there within can be found the divine. As such, in contrast to the monist cosmology of the ancient Gnostics, Jung’s Gnostic vision is panentheistic. Panentheism (from the Greek pan “all”, en “in”, and theos “God” [i.e., “all in God”]), in distinction to pantheism, is the metaphysical doctrine that considers God to be greater than the universe, both containing it and interpenetrating it. God is simultaneously transcendent and immanent. Pantheism (from the Greek, meaning “all is God”), on the other hand, ideies God with the universe, in other words, the universe is God manifest, and God is the universe un-manifest (Figure 6).

However, despite a general absence of panentheism in Gnostic scripture, there is at least a hint of it in The Gospel of Philip which suggests that, rather than the usual characterisations of the divine realm as “higher” and the created realm as “lower”, it would be better to reframe these as “inner” and “outer”. Drawing on the following passage from the canonical Gospel of Matthew, “When thou prayest, enter into thy closet, and when thou hast shut thy door, pray to thy Father which is in secret” (Matthew 6:6, KJV), Philip asserts that what is innermost is the fullness of the Pleroma and what is outermost is the darkness of the corrupt world. Jung’s model of the Pleroma would fit more readily to the inner/outer model (minus the corruption) than the higher/lower model that characterises most of Gnostic thought. Jung’s vision also shares the panentheism of the Corpus Hermetica which teaches that it would be incorrect to think that matter could exist apart from God. If it did, it would be nothing but a confused mass. Matter is inherently ordered and that order is of God. The energies that operate within matter are parts of God who is in all. In the Hermetic view, there is nothing that is not God.

For Jung, like the Hermeticists, if not the Gnostics, the Pleroma interpenetrates the material world and the distinction between the immaterial and the material is one of quality, or state, rather than a spatio-temporal separation.

Jung’s Gnostic cosmogony also differs from that of the ancient Gnostics’ in terms of process. Expanding on the concept of emanation of the binary pairs of opposites, Jung’s account stresses the crucial importance of the differentiation of the opposites in the act of creation. For Jung, differentiation is creation, and without the differentiation of the opposites, there can be no creation. Without differentiation, the syzygies of the Pleroma remain inert and exist, insofar as they can be considered to exist at all, as potentials only. Through the process of differentiation, these original unified “pairs”—we cannot really call them pairs in their unified, undifferentiated state—are split into a dyad of complementary, yet polar, opposites, both of which are required to reconstitute the whole. Nothing can exist without the simultaneous existence of its complementary opposite. There is no hot without cold, no light without dark. In the Pleroma, prior to differentiation the opposites cancel one another out and are ineffective and not “real”. Only once differentiated do they come into effect and become what we might consider as “real”. Consequently, as created beings, the fundamental characteristic of human nature in Jung’s Gnostic thinking is the differentiation of the opposites. This differentiation of the opposites would become the crucial factor and the hallmark of Jung’s psychology.

Also lacking from Jung’s Gnostic creation myth is the notion that the world came into being through error. Indeed, in sharp contrast, Jung’s view was that the process of emanation/differentiation of the pairs of opposites was to be regarded, not as a mistake, but far more positively as the origin of life itself (McGuire & Shamdasani, 2012).

***

In the fashion of the Gnostic myths of antiquity, PKD’s Gnostic cosmogony also begins with the monad, which he defines in his Exegesis, quite simply, as the “sentience in the cosmos which understands” (2011, loc. 7129). Out of this monad the opposites emerge. In the Tractates Cryptica Scriptura he writes, “One Mind there is; but under it two principles con-tend” (2001, p. 257). Sharing the paradoxical nature of Jung’s Pleroma, PKD’s ultimate reality, the One Mind, both is and is not. PKD describes a two source cosmogony that resulted from the One’s desire to differentiate the “was-not from the was” (p. 266). Like Jung’s Gnostic myth, differentiation is at the very heart of coming-into-beingness in PKD’s gnosis. This desire to differentiate led to the formation of what he refers to as a “diploid sac” containing a pair of androgynous twins, spinning in opposite directions, symbolising the yin and yang of Taoism with the One representing the Tao itself. Diploid (from Greek diploos, meaning double) is a biological term that refers to a cell containing two sets of chromosomes, typically one set from the mother and the other from the father. Thus, PKD’s use of the term “diploid” highlights the primary syzygy fundamental to Gnostic cosmogony. Taoism had a profound influence on PKD’s worldview (as it did on Jung’s) and this influence is evident here. Strong parallels between PKD’s cosmogony and the teachings of the Tao Te Ching are clear. For example,

There was something undefined and complete, coming into existence before Heaven and Earth. How still it was and formless, standing alone, and undergoing no change, reaching everywhere … It may be regarded as the Mother of all things.

(Chinese philosopher Lao-Tze)

Like the classic Gnostic myths, and in contrast to Jung, PKD’s cosmogony also results from an error. The original plan of the One was for the androgynous twins to be birthed from the diploid sac simultaneously. However, in an act reminiscent of Sophia’s desire to create on her own as found in The Secret Book of John, the anticlockwise twin, motivated by the desire for existence, emerged from the sac prematurely and defectively, somewhat akin to Sophia’s bastard child, the demiurge. PKD refers to this premature twin as the dark, yin twin. The other, the yang twin, which PKD describes as wiser, only emerged at full term and was without defect. The result was that each twin was “a unitary ent-elechy, a single living organism” (2001, p. 266) consisting of both psyche and soma, but continuing to spin in opposite directions. However, the premature birth of the yin twin gave rise to a decaying condition which introduced “malefactors”—much like the demiurge and the archons—which, in turn, led to the origin of “entropy, undeserved suffering, chaos and death” (p. 266) and what PKD would refer to as the Black Iron Prison (see below). Elsewhere, consistent with the Gnostic view that the created world came into being as a result of a rupturing of the divine harmony of the aeonic syzygies, PKD (2008) asserts that the created world resulted from a rupturing of the Godhead. Due to a “primordial schism” (p. 158), part of the Godhead remained in the transcendent realm, and the other part became debased and fell to become the created world. Consequently, the “Godhead [has] lost touch with a part of itself” (p. 158, emphasis in original).

Following the emanation of the original twins, the next step was that the two became many through a process of dialectical interaction in which “[F]rom them as hyperuniverses they projected a hologram-like interface, which is the pluriform universe we creatures inhabit” (Dick, 2001, p. 266). Once established, the universe needs to be maintained by an equal intermingling of the original twins. Thus, for PKD, as for Jung, the universe remains in existence due to the interaction of the opposites. PKD’s cosmogony is undoubtedly a unique variation on the theme, but it is unmistakably Gnostic at its core. It results in two realms (Figure 7), the upper, or yang, which he describes as sentient and volitional, and the lower, or yin, which he describes as “mechanical, driven by blind, efficient cause, deterministic and without intelligence, since it emanates from a dead source” (ibid., p. 269). Like the ancient Gnostics who believed we were trapped in an alien world, and estranged from the Pleroma, PKD believed that we are trapped in the lower realm.

A key feature of PKD’s Gnostic cosmology is its acosmic panentheism. PKD defines panentheism as a metaphysical doctrine that states that God is simultaneously both transcendent and immanent, in other words, both beyond all, yet within all (2011, loc. 18161). Like Jung, PKD’s Gnostic vision echoes The Gospel of Thomas in which the divine can be found when a piece of wood is split or when a stone is lifted up. PKD’s panentheism led him to claim that God is as near at hand “as the trash in the gutter—God is the trash in the gutter, to speak more precisely” (1977). This notion immediately brings to mind Christ’s birth in a stable among the animals. It is also reminiscent of the alchemical concept of lead being turned into gold or, rather more prosaically, the shit of daily life is the raw material for the transformation of the individual soul. Acosmism, on the other hand, is a metaphysical or philosophical concept that denies any substantial reality to the universe. Instead, only the absolute has any reality and the universe is merely an illusion. Combined, with panentheism, acosmic panentheism posits an ultimate divine reality greater than, and encompassing, an unreal, or illusory, universe (Figure 8).

Figure 7. The upper and lower realms in PKD’s Gnostic vision.

For PKD, God is greater than the world, or the universe, and only God is wholly real. However, God is enshrouded in an illusory “veil of appearance” (2011, loc. 4910) which PKD likens to a muaceted sphere where each facet emits a coloured light, somewhat akin to the mirrored disco balls of yesteryear. According to PKD, acosmism is intrinsic to the gnosis of the Gnostics (loc. 9324).

***

The Gnostic cosmogonies of Jung and PKD share a number of significant correspondences; however, they differ in the detail, with perhaps the most fundamental difference between their respective visions being that for Jung the universe is real—at least, he does not appear to have questioned its fundamental existence—whereas for PKD, it is not real. This theme will be explored in greater detail in a later chapter.