CHAPTER ELEVEN

Slavery and freedom

Ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free.

—John 8:32, KJV

The only goal of the Gnostic is to return to the Pleroma. For the Gnostic, salvation is the liberation of the divine spark from the spatio-temporal, material prison world, and its reinstatement to the realm of light, or into the depth and silence. Whereas the Neoplatonist might seek a return to the One, the Gnostic seeks a return to the Zero, in other words, the Nothingness of the Pleroma. In the text known as On the Origin of the World it is stated that the light will overcome the darkness and that the darkness will be dissolved, before adding that everyone must return to the place where they came from. That is, everyone must leave the world of darkness and return to the source of the light and eternal rest in the depth and silence of the Pleroma. The Gospel of Philip notes that when the bride and bridegroom come together in the mystical marriage there is only one name for their union and that is rest; the rest that results from nothing but the pure contemplation of the divine. As the saviour said, “Come unto me, all ye that labour and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest” (Matthew 11:28, KJV). Or, in the words of Meister Eckhart, God is at home and it is we who have gone out for a walk. Gnostic salvation requires an end to our wandering in the valley of death and our homecoming to rest in the Pleroma.

The various texts of the Nag Hammadi Library highlight various aspects of this return journey. Paramount among these is, of course, the need for gnosis, the sine qua non of Gnostic salvation and the return to the Pleroma. The Gospel of Philip teaches that ignorance, the antithesis of gnosis, is the mother of all evil and leads to death. Citing John 8:32, “Ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free” (KJV), Philip adds that ignorance is slavery, and gnosis is liberation. If a person knows the truth, she will find the fruit of that truth, and if she joins with that truth, it will bring fulfilment, in other words, a return to the Pleroma. Salvation is often referred to as the resurrection in the Gnostic texts and in his introduction to The Treatise on Resurrection, Thomassen (2007) notes that the resurrection and return to the original purity of the Pleroma, dependent on salvific gnosis, includes the realisation that our spiritual essence is something that we already possess. It is not something that we need to develop, it is something we need to realise. In this regard, Gnostic salvation is somewhat akin to the Dzogchen tradition in Tibetan Buddhism in which liberation involves awakening to one’s true nature. In the case of the Gnostic, the true nature is that one’s spiritual essence is the divine spark. One is already of the Pleroma, in the Pleroma, and permeated by the Pleroma. Seen in this light, the resurrection is anamnesis of our divine heritage rather than an event. Upon this realisation, the attainment of gnosis or enlightenment, one realises, for the first time, one’s perfection. The Gnostic returns to the Pleroma transformed, or, in the words of the poet T. S. Eliot, after a peregrination through the material realm, one returns to the Pleroma with gnosis as if for the first time. Essential to this realisation is, amongst other things, the awareness that the spatio-temporal nature of our so-called reality is merely part of the archons’ deception. Nevertheless, according to Thomassen, in the case of the Gnostic, more than this awakening is required. The soul, as a potential Christ, must incarnate and attain the resurrection, as a necessary precondition for the restoration of the original perfection in the Pleroma. As such, there is “both an ‘already’ and a ‘not yet’” (ibid., p. 51) aspect to Gnostic salvation. The “already” part is the perfection of the indwelling divine spark. On the other hand, the “not yet” part demands the efforts of the Gnostic, and The Treatise on Resurrection informs us that, although we already have the resurrection, we carry on in our earth-bound zombie state as if we will die, without realising that the mortal part of us is as good as dead already. The text makes it clear that everyone must practise ways to escape from this prison world, otherwise they will continue to be led astray and kept in ignorance. Blind faith in the saviour is not enough. Receptivity to the spirit, and the salvific gnosis that is brings, coupled with one’s own efforts are required to attain liberation.

In order to achieve salvation, or the resurrection, and the return to the Pleroma the Gnostic texts teach that one must first escape from the prison of matter imposed on humanity by the archon slave masters. The Teachings of Silvanus implores the reader to which it is addressed to prepare to escape the archon-controlled world of darkness by turning his back on the things of the world in which there is no profit. Instead, he must purify his outer life in order that he may be able to purify his inner life. Similarly, The Dialogue of the Saviour—which some would argue is not truly a Gnostic text—recounts, as the name suggests, a supposed dialogue between the disciple Matthew and the saviour. Matthew asks why we do not go to our rest at once. In other words, why do we not return to the Pleroma immediately? The saviour replies that we will rest only when we leave behind what cannot accompany us (i.e., the physical body) and all that burdens us. For the Gnostics, the resurrection is not a bodily one, but the reverse, an escape from all that is material. Similarly, The First Revelation of James states that we will not be saved until we “throw off blind thought, this bond of flesh surrounding [us]” (Meyer, 2007, p. 325). Taking an equally dim view of the human body, The First Revelation of James views the crucifixion as esoteric symbolism rather than as a historical event, and speaking from the perspective of the Christ within rather than as the earthly human, states that the saviour did not suffer. He, as Christ, was neither distressed nor harmed; rather, the crucifixion was “inflicted upon a figure of the rulers, and it was fitting that this figure should be [destroyed] by them” (p. 327). The saviour continues that the flesh is weak and it will get what has been ordained for it. The biblical aphorism, “Render therefore unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s; and unto God the things that are God’s” (Matthew 22:21, KJV) comes to mind once more. Caesar is a symbol of the demiurge, the emperor of the Empire, who presides over the Black Iron Prison. The body belongs to the archons and returns to the dark lords of matter, the spirit belongs to the Pleroma. The soul is crucified between spirit and matter, and must choose the way in which it will go. The Gospel of Philip states that as long as what it refers to as the root of wickedness is hidden it remains strong. However, when it is recognised, it will be dissolved. It only has power over us because we have not recognised it. The root of wickedness is the deceit of the archons, and they only have power over us because we have not seen through the veils of deception and realised our imprisonment in matter. This would later find an echo in Jung who taught that we do not attain gnosis by imagining beings of light, but only by making the darkness conscious, an endeavour that is so disagreeable that it is generally eschewed. For anyone making a reasonable analysis of the Gnostic literature, there can be no shadow of a doubt that the Gnostic pastors of antiquity considered this world to be a corrupt, fallen place and they wanted to get the flock out of here. At the end of The Matrix, Neo claims that despite our desire to change the world the Matrix will remain our cage. We cannot change the cage; nevertheless, it can become our chrysalis in which we are transformed; but to be liberated we have to change ourselves. The Black Iron Prison can simply imprison us, or it can rehabilitate us. The prison is not going to change, or at least, not until we do. Echoing the reputed words of Gandhi, we need to be the change. Jung’s view was the change had to begin with the individual: it does not happen “out there”, it happens “in here”.

According to the Authoritative Discourse, the choice of life or death is offered to everyone and each must choose for himself or herself. In regard to this choice, Meyer (2007) refers his reader to a number of similar passages of canonical scripture including the following: “Verily, verily, I say unto you, he that heareth my word, and believeth on him that sent me, hath everlasting life, and shall not come into condemnation; but is passed from death unto life” (John 5:24, KJV). In Gnostic terms, whoever receives the saviour’s gift of gnosis and applies that knowledge to attain liberation crosses from death to life. Later in The Gospel of John Christ declares,

Verily, verily, I say unto you, I am the door of the sheep. All that ever came before me are thieves and robbers: but the sheep did not hear them. I am the door: by me if any man enter in, he shall be saved, and shall go in and out, and find pasture. The thief cometh not, but for to steal, and to kill, and to destroy: I am come that they might have life, and that they might have it more abundantly. (John 10:7–10, KJV)

To the Gnostic, this passage states that the realised Christ opens the door to the Pleroma for the Gnostic faithful. The thieves and the robbers are the deceptions of the archons who keep us enslaved and obscure the way back to the Pleroma. The archons come to steal, kill, and destroy. Likewise, in The Wisdom of Jesus Christ, the saviour comes to free the immortal human from the bondage of the robbers. As Morpheus says in The Matrix, humanity will never be free as long as the Matrix, that is, the illusory, archon prison world, is in existence. The red pill or the blue pill? In The Exegesis on the Soul, the first step in making the choice, and the beginning of salvation, is repentance from the animal soul’s “former whoring”. Salvation is achieved when the soul reunites with spirit and consummates the mystical marriage in the bridal chamber. This is the resurrection from the dead, freedom from captivity in the world of matter, and the return to the Pleroma. The Exegesis on the Soul also makes reference to Luke 14:26—which states that if one does not hate one’s own life, one cannot be a disciple of the saviour—and notes that one must, not only hate one’s own life, but must hate one’s own soul in order to follow the saviour. The soul being referred to is the animal soul of the archons, not the living soul from the Pleroma. The Gnostic must forsake this earthly life of captivity and “hate” his, or her, animal soul.

Regarding the fate of the human soul the Gnostics believed that not all souls will be saved. For example, the interlocutor in The Secret Book of John asks if all souls will be saved and returned to the Pleroma. The saviour responds that only those on whom the Spirit of Life descends can be saved. Without the Spirit of Life an individual cannot even stand up which, symbolically, as Smith (2008) has pointed out, suggests that the soul is unable to raise itself above the material plain of existence. In the Gnostic tradition the descent of Spirit on its own is not enough; the soul must play its part and only those who have received the Spirit, and who reject the wickedness and corruption of this world, “expunge evil” from themselves, and avoid being led astray by the counterfeit spirit of the archons, will inherit eternal life. On the other hand, those souls in whom the counterfeit spirit has grown strong will be burdened by the fetters of matter once more, cast back into the wickedness of the world and blinded once more by the veil of deception spun by the archons. At the time of physical death when these souls leave the body they will be given over to the archons, bound in chains, and immured once more in the Black Iron Prison. Espousing the concept of reincarnation, The Secret Book of John teaches that the cycle of rebirth into this world continues until the soul attains the gnosis that lifts the veil of deception and, through its efforts, realises perfection and is saved, returning to a state of eternal repose in the Pleroma. The Gnostic tradition affirms the doctrine of reincarnation, and it appears in a number of places in the Gnostic literature; however, it does not appear to be something the Gnostic should be overly concerned with. The task of the Gnostic is to escape from the material world, and return to the Pleroma, whilst in this present incarnation. The interlocutor, John, then asks about the fate of those souls who have achieved true knowledge but have then turned away from it. Reminiscent of the teaching that those who blaspheme against the Holy Spirit will never be forgiven, but are in danger of eternal damnation (The Gospel of Mark, 3:29, KJV), the saviour answers that they will be ushered to a place where the “angles of misery go” (Meyer, 2007, p. 129) and where repentance is impossible. There, they will be held until “those who have blasphemed against the spirit will be tortured and punished eternally” (p. 129). In similar vein, The Gospel of Philip teaches that people who have been enslaved against their will can be freed; however, those who have been freed by their master and then sell their souls back into slavery can never be freed again. On the other hand, regarding the fate of the divine spark, the spirit within us, it will return to the Pleroma. In truth, it never really left, because it is the Pleroma. It is merely the archons’ veil of deception that gives us the illusion that we are not from the Pleroma, and are separated from it. God is at home, it is we who have gone out for a walk … and got lost in Dante’s dark wood along the way.

Another feature of Gnostic soteriology is the idea that it involves an ascent through a series of planes in order to reach the transcendent realm of light. These planes are thought to be controlled by the archons and the aspiring Gnostic must carefully navigate a way past the archons who will do what they can to thwart the Gnostic’s efforts and keep him, or her, enslaved in the lower realms. In the Gnostic tradition, the Pleroma is considered “higher”, and the fallen world of the archons “lower”. However, the “ascent” ought to be seen as metaphorical, and is not to be thought of as a movement upwards. It should be considered as an expansion of consciousness and an increase in gnosis. Turner (2001) identifies two patterns of soteriology in the Gnostic texts attributed to the Sethian sect. The first, which he refers to as the descent pattern, involves the saviour who descends from the Pleroma with gnosis. This intercession from above by the saviour has been discussed in a previous chapter. The second, the ascent pattern, is described by Turner as gnosis attained by contemplative ascent. The first requires the Gnostic to become receptive to the saviour and to receive gnosis as a gift through grace. The second need to be worked for and attained through the Gnostic’s own efforts. The texts which elaborate on the theme of the ascent pattern present salvation as a contemplative journey involving a visionary ascent through a series of inner planes. The process is one of self-realisation in which the way of ascent is the reverse of the original descent from the source. It entails an undoing of the process of emanation out of the Pleroma, and culminates in a return to, and a dissolution in, the highest transcendent realm. Typically, these inner planes correspond to the planets, each of which is characterised by the unique challenges it represents to the Gnostic aspirant. These challenges are nothing but the archons’ attempts to keep the Gnostic soul trapped in the world of shadows. Turner suggests that these visionary ascents are not necessarily one-off events in which gnosis is acquired in the mother-of-all mystical experiences—but let’s not rule that out—rather, he considers them to be brief events during the life of the Gnostic, which provide a foretaste of the ultimate ascent the soul will make following the death of the body. This idea is captured eloquently by the French writer and poet, René Daumal (1908–1944):

You cannot stay on the summit forever; you have to come down again. So why bother in the first place? Just this: What is above knows what is below, but what is below does not know what is above. One climbs, one sees. One descends, one sees no longer, but one has seen. There is an art of conducting oneself in the lower regions by the memory of what one saw higher up. When one can no longer see, one can at least still know. (2017)

Like one of those computer games that has multiple, increasingly difficult levels where it takes many attempts and many hours of practice to reach the higher levels, the attainment of gnosis is, no doubt, a process of incremental gains over a lifetime of dedicated practice. After each partial trip up the mountain to render unto God what is God’s, the Gnostic practitioner returns, with a little more gnosis, to the world and, out of necessity due to the limits of the body, to the task of rendering unto Caesar while preparing for the next attempt at the summit. In the words of the Buddhists: before enlightenment, chop wood and carry water; after enlightenment, chop wood and carry water.

A crucial component of Gnostic soteriology, and one that would have a particularly profound influence on both Jung’s gnosis and his psychology, is the need to both a) reconcile the opposites, and b) in the case of the Gnostics, realise the ultimate dissolution of the opposites in the Pleroma. The Gospel of Thomas teaches that if one is whole then one will be filled with light, but if one is divided, then one will be filled with darkness. In other words, when one has integrated the opposites, when the bride and bridegroom have consummated their mystical marriage in the bridal chamber, then one will be filled with the light of the Pleroma. On the other hand, as long as the opposites are differentiated, and the bride has forsaken her betrothed and continues whoring, one remains condemned to the darkness of the world. These are fundamental distinctions in the Gnostic tradition: the Pleroma is characterised by light and wholeness; this world is characterised by division and darkness. The Wisdom of Jesus Christ speaks of the need to be united with spirit such that two become one as it was in the beginning. The Gospel of Thomas elaborates further on the theme and claims that one will only return to the Pleroma when the two are made into one, when the inner is made like the outer, and the outer like the inner, when upper and lower are reconciled, and when the male and the female are reunited into a single being so that their gender differentiation is dissolved. Then, and only then, will the Gnostic see the light of the Pleroma. Meyer (2007) notes the close correspondence to the following passage from canonical scripture:

For as many of you as have been baptized into Christ have put on Christ. There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus. (Galatians 3:27–28, KJV)

The balancing, and ultimate dissolution, of the male/female polarity is also captured by the Indian mystic Ramakrishna (1836–1886). In reference to Brahman, the ultimate male divinity in Hinduism, and Shakti, the creative power of the divine feminine, Ramakrishna is said to have proclaimed that Brahman is Shakti, and Shakti is Brahman. They are not to be considered distinct but two aspects, one male, and one female, of the same Absolute. The Tripartite Tractate also states that the return to the primal unity of the Pleroma is premised on the balancing of the opposites. The return, like the beginning, is unitary where there is neither male nor female, neither slavery nor freedom, neither immortal being nor mortal being. All that will exist is the perfect balance of the opposites such that they cancel one another out which, in this particular text, is symbolised by the figure of Christ. The description of the Pleroma as a state of rest has already been noted, and this state includes all syzygies in a perfect state of harmonious equipoise, no movement, no vibration, no sound, just silence. As Eckhart expressed it, there is nothing so much like God in all the universe as silence. Elsewhere Eckhart described the quiet mind that contemplates the Godhead as one on which nothing weighs, one free from worries and the ties that bind it to the world, free from all self-seeking, but wholly merged with the Godhead and dead to any notion of a separate self.

* * *

A WWII radio operator is in discussion with his German counterpart. “We” (presumably, the British) seem to be holding the German’s brother as a POW. When I realise this, I take over the conversation with the German radio operator and arrange a prisoner swap, one of ours being held captive by them in exchange for his brother.The exchange takes place on neutral ground between our respective sides’ front lines. At the end of the exchange I want to meet and shake hands with the German radio operator. I tell him that when the war is over and peace is restored I will meet him in Germany and we will play chess, drink beer together, and watch the sunset.

(Author’s dream journal, November 2016)

This dream largely speaks for itself and little commentary is required. It is clearly a reiteration of the passage from The Gospel of Philip that teaches that light and darkness, and life and death, and left and right, are siblings which cannot be separated. Consequently, good is not good, evil is not evil, life is not life, and death is not death. Each pair comprises the complementary poles of an underlying unity which have become differentiated. Ultimately, symbolically representing by the setting sun, each pair of opposites will dissolve back into unity. This concept of sibling polar opposites dissolving into unity is symbolised by the German radio operator and his brother being reunited. Elsewhere The Gospel of Philip makes it clear that when Adam and Eve were conjoined there was no death. Only when they were separated did death come into being, and only when they reunite will death cease to be. In other words, only when the primal syzygy differentiated into its opposing poles on the plane of matter, when the male and female split, did death come. Paradoxically, as is the way with the opposites, not only did the differentiation of the opposites create the energy potential essential for life, that same differentiation also instituted death. Life and death are siblings, which, in characteristic fashion, the Gnostics have flipped on their heads: to be born into this world is death; to escape this world and return to the Pleroma is life.

The dream also symbolises the way in which opposites are reconciled within the psyche according to Jungian psychology. Given his view that the psyche is a self-regulating system forever seeking psychic equilibrium, Jung believed that any exaggerated conscious attitude is compensated by an equal and opposite unconscious counter-position. As opposites, the conscious and unconscious attitudes are the two poles of an underlying unity, and their reconciliation and integration involves elevating consciousness to a level that transcends the separation of the poles and realises their inherent unity. According to Jung, this is achieved through a dialectic exchange (symbolised by the communication with the German radio operator) between the ego (i.e., the conscious attitude) and the unconscious counter-position, in which both positions are given due regard and any notion of right/wrong valuation is suspended. The two opposing positions will generate what Jung describes as an energy tension within the psyche. If the person can hold this tension of the opposites during the ongoing dialogue between conscious and unconscious attitudes, a third position, embodying the inherent unity of the opposites, will emerge that transcends the two opposites. This third position becomes the new conscious attitude to which the unconscious, once more seeking compensatory balance, responds with a further counter-position. The dialectical exchange begins anew and repeats ad infinitum, presumably, or until the person has achieved the idealised, but practically unattainable, goal of complete psychic integration. This process, as well as the resultant third position, Jung termed the “transcendent function” (1957b), and the method he developed to achieve it was active imagination (see above). The dream is suggesting that the opposite positions in the archetypal battle of good vs. evil, symbolised by the British at war with the Nazis, need to be transcended, and a higher level of consciousness attained that recognises their underlying unity in which good is not good, and evil is not evil. Furthermore, the chess symbolism reframes the clash of the light and the dark, symbolised by the white and black pieces, as a game. This is bitter medicine, and it is difficult to come to terms with it in the face of the horrors that unfold daily on prison Earth. Perhaps when good and evil have been dissolved, and duality has been transcended, we can look down from a place of higher consciousness, and see the struggle of the light and the dark within human experience as a game. This is hard to do from the perspective of a pawn within the game. However, in PKD’s view, we are the archons, and the archons are us, and when the war is over, hopefully we can share a beer with our archonic shadows. We do not need to like the way they play the game, but, ultimately, before the sun sets, we need to learn to love them. This might be the most bitter medicine of all; to love the darkness within.

* * *

The Gnostic texts of the Nag Hammadi Library are permeated by an asceticism of one degree or another, ranging from the moderate to the severe. The Gospel of Thomas declares that those who do not fast from the world will not find the Kingdom of Heaven. Fasting does not simply mean abstaining from food and drink—although, to some extent, this is no doubt required—but rather it refers to a letting go of the fetters of matter, the passions of the mind and the flesh, and everything that binds us to the world of shadows. According to the Gnostic tradition, this includes sexual restraint or abstinence, whether temporarily or permanently. In The Testimony of Truth it teaches that the saviour descended from the Pleroma by way of the River Jordan, which immediately turned back on itself, bringing an end to the “dominion of carnal procreation” (p. 617). The Testimony makes it clear that reference to the River Jordan is esoteric symbolism for the physical body and the pleasures of the senses. Specifically, the waters of the Jordan refer to the desire for sexual intercourse. The text continues that only someone who completely renounces the things of the world and subdues the passions can realise the truth of God. The Gospel of Philip acknowledges the great mystery of marriage, including its carnal expression. Without it, the world could not exist for the world, as humanity experiences it at least, is inherently dependent on people, and people could not exist without marriage (and the procreation that typically results from it). However, the text cautions that the power of the pure intercourse of the mystical marriage, which occurs in a realm superior to this one, has become defiled in its image on Earth, that is, the carnal marriage. Philip makes an unambiguous distinction between what is referred to as the marriage of defilement, fuelled by the carnality of sexual desire, and the undefiled marriage of metaphysical union driven by pure thoughts directed by the will. The marriage of defilement is associated with darkness and the night in which the fire of the passions flickers briefly and then is quickly extinguished. On the other hand, the undefiled marriage is characterised by the day and the holy light, and neither the day nor its light ever sets. Furthermore, only one who accomplishes the rite of the mystical marriage will receive the holy light, and if it is not received in this realm, it cannot be received in any other place. The Exegesis on the Soul also makes the same sharp contrast between the mystical union of spirit and soul in the bridal chamber and the marriage of the flesh. The Gnostic teachings on sexuality are, of course, deeply unpopular and, unsurprisingly, commentaries on the Gnostic texts tend to gloss over this aspect of the teachings if, indeed, they make any reference to it at all. There are some who might like to dismiss the teachings of the Nag Hammadi Library, including what they say about sexuality, as merely the “outer” teachings of the Gnostics, and claim that the real, “inner” teachings were reserved for the select, initiated few. The implication is, of course, that the person making such a claim is one of the enlightened few. Yes, secret teachings are often referred to, even in canonical scripture, for example,

And he said unto them, “Unto you it is given to know the mystery of the kingdom of God, but unto them that are without, all these things are done in parables, that seeing they may see, and not perceive; and hearing they may hear, and not understand; lest at any time they should be converted, and their sins should be forgiven them.” (Mark 4:11–12, KJV)

Notwithstanding such claims, or the accusations of the Gnostics’ detractors—which must be taken with a liberal dose of salt—if we want to understand the Gnostic tradition, we have little reasonable recourse other than to take the Gnostic texts at face value. The Gnostic schools were extant between the second and fourth centuries CE when the Christian horse race had been run, a winner declared, and the establishment of an institutionalised Church as a means of control was underway. During this time, the Church heresiologists, such as Irenaeus, Hippolytus, Tertullian, Clement, and Origen, set about the condemnation and suppression of the teachings of all other horses in the race, especially those of the Gnostics, who claimed that the divine could be accessed through direct inner experience without the need of a Church as intermediary. Seen in the light of the Church’s agenda, the heresiologists’ vitriolic attacks against the Gnostics need to be regarded as questionable. (Personally, I am disinclined to take too seriously those who had no qualms about burning others at the stake for simply disagreeing with them over a minor point of theology—although it was never about theology, it was about control.) Whereas claims of a secret inner teaching cannot be disproved, in the face of such claims, a certain amount of caution ought to be observed. Perhaps the true secret teachings are those that are to be found within. Jung claimed that the person who looks outside is a dreamer, and that the person who looks inside for salvation awakens. “When thou prayest, enter into thy closet, and when thou hast shut thy door, pray to thy [God] which is in secret” (Matthew 6:6, KJV). The blatant dismissal of the Gnostics’ teachings on sexuality might well be one of those blue pill moments. You can take the blue pill, wake up in your bed, and believe whatever the archons want you to believe.

* * *

Whereas in the Gnostic tradition there is no doubt that the ultimate destination of the Gnostic soul was a return to the Pleroma, the ultimate destination in the Seven Sermons is quite different. Indeed, in some respects, Gnostic and Jungian eschatologies take opposing views. Although in his memoirs, Memories, Dreams, Reflections (1962)—written very late in his life—Jung speculated about what happens after death, in his public psychological works he avoided statements about the fate of the soul after the death of the physical body. For example, in his “Psychological Commentary on ‘The Tibetan Book of the Dead’” (1957), he claimed that we “know desperately little about the possibilities of continued existence of the individual soul after death, so little that we cannot even conceive how anyone could prove anything at all in this respect … such a proof would be just as impossible as the proof of God (p. 67). How-ever, in his Gnostic vision, the Seven Sermons, Jung postulates that the place an individual soul goes to rest after the death of the body is a star located at an inestimable distance in the zenith of the firmament. In the words of musician David Bowie—who some claim was influenced by the Gnostics—there is a star man waiting in the sky. However, rather than him come to meet us, we are to go and meet him. Hopefully, he will not blow our minds. According to Jung, there is one star for each individual and this personal star is both the individual’s god and goal. Jung contrasts this world as the dark, chilling moisture of nothingness, ruled by Abraxas, compared to the eternal sunshine of the creative power of the star. Nothing prevents the individual completing the long journey to the distant star at death provided he, or she, can avert his, or her, gaze from what Jung describes as the flaming spectacle of Abraxas (2009). In other words, only succumbing to the pull of the opposites can stop the individual from attaining final repose in the star. For the ancient Gnostics, the task was to seek a return to the original state of the Pleroma prior to the emanation of the first aeons, whereas in Jung’s gnosis the task was to aim for the stars, a destination far removed from the original source. Paraphrasing the words of the playwright Oscar Wilde, we are all in the gutter of this archonic world, but some of us are concerned about escaping to, or beyond, the stars.

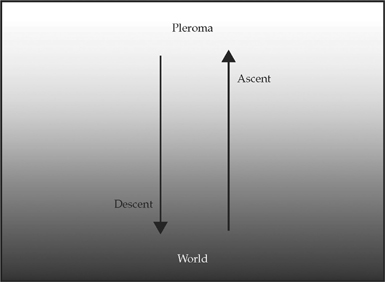

To some extent Jung’s eschatological star god in the Seven Sermons feels like an avoidance. He seems to push the problem of the ultimate fate of the individual to somewhere way “out there”. In effect, he does not really deal with it adequately. To be fair, the Seven Sermons was written in his mid-life when he had only really begun an earnest exploration of his own inner world. He was still in the throes of his confrontation with the unconscious and, no doubt, had not attained the fully individuated state. Perhaps, having not achieved the ultimate goal of psycho-spiritual development and simply not having had the experience—obviously, he had not experienced the after death state—he did not feel qualified to incorporate individual eschatology as a fully worked out, integrated aspect of his Gnostic vision, and included brief, speculative comments only. This ought to be commended for its intellectual honesty, yet the star god finale in the Seven Sermons remains somewhat unsatisfactory. Perhaps this explains why the emphasis in the Seven Sermons shifts very quickly from a metaphysical focus to a psychological one and, as such, it is not a cosmological process that is being described, but the birth of consciousness. In short, Jung’s Gnostic vision, and particularly his psychology, founded in large measure on the former, is at odds with the Gnostics of old in terms of the ultimate goal. For the Gnostics, this world, created in error, was seen as a prison from which humanity was to escape. They thought that we have been cast into this world (descent), without our consent, and remain imprisoned through the archons’ deception. We are not here to redeem or transform the world in any way. Our task is simply to extricate ourselves and return to the source (ascent). This is the descent/ascent pattern (Figure 17) of Gnostic soteriology that has been discussed above.

On the other hand, unlike the bidirectional pattern of Gnostic eschatology, in which the path of ascent retraces the steps of the prior path of descent, Jung envisaged a linear psycho-spiritual developmental journey from an unconscious Godhead to a fully realised Self. Jung’s Gnostic eschatology of the individual involves a tripartite linear trajectory from 1) the undifferentiated opposites which cancel each other out in the Godhead (Pleroma), through 2) the state of differentiated opposites which give life its spark and allow the world to come into existence, to 3) a final state in which all opposites have been reconciled, integrated, and ultimately unified (the Self). However, the crucial difference between the first and final state is that, rather than the opposites dissolving into one another and cancelling one another out on the return, the final state is one of harmonious balance of the opposites in which they retain at least some degree of differentiation. (When researching this idea for my first book I had a dream in which this idea of the fully integrated-yet-differentiated opposites was symbolised by a man and a woman, cheek-to-cheek, dancing the tango. Two harmonious opposites, perfectly synchronised, but only one dance.)

Consequently, the defining feature of Jungian Gnostic soteriology, one that does not have the same degree of emphasis in the Gnostic texts, is the need for a growth in consciousness in this life. According to the Gnostics we are, metaphorically, nothing more than a bunch of drunken, somnambulist zombies who have fallen prey to the veil of ignorance spun by the archons that keeps us imprisoned in the world of matter. Jung, no stranger to bluntness himself, was somewhat more circumspect in regard to our fallen state, and noted that humanity’s worst sin was unconsciousness. Therefore, the key to salvation in Jung’s Gnostic vision, which would directly influence his psychology, is to become more conscious. In Gnostic systems, the archons that keep humanity imprisoned are not so much to be seen as evil—although their effects are very much evil—rather they are to be seen as being ignorant, and of a very limited, unfeeling, robotic consciousness. As a result, the key to achieving salvation is not so much overcoming evil, but about becoming more conscious, and this pursuit of increasing consciousness is certainly the direction taken by the soteriological aspects of Jung’s gnosis. However, whereas for the Gnostics, gnosis was a means to an end, and that end was escape, for Jung, gnosis, in terms of expanded consciousness, was both the means and the end itself in many ways.

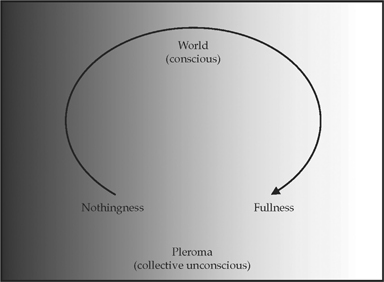

For the Gnostics the return to the Pleroma involved a dissolution of the opposites back to their original, non-differentiated state. However, for Jung, this dissolution posed a great danger and was the sin of unconsciousness, and a retreat back into nothingness and non-existence, in other words, death. As has been noted above, in Jung’s view, life is dependent on differentiation. No differentiation, no life, and without life there can be no growth in consciousness. Consciousness demands the differentiation of opposites, and growth in consciousness demands the reconciliation and integration of the opposites. Differentiation of the opposites is what saves humanity from unconsciousness. Yet, in Jung’s view all of humanity’s problems result from the splitting of opposites in the psyche, both the personal psyche, and the collective psyche. Reconciliation and integration of the differentiated opposites is what saves humanity from life. If there is to be any concept of a return in Jung’s gnosis it would be from the original nothingness of the Pleroma, via the differentiated opposites of creation, returning to the fullness of the Pleroma (Figure 18). Indeed, Jung does refer to the star that each individual goes to after death as their individual pleroma. Alternatively, the goal in Jung’s Gnostic system sees the fulfilment of the journey from an unconscious Godhead to the realisation of a fully conscious God.

Given the emphasis on psychological growth in Jung’s Gnostic system, the struggle for salvation does not pit aeons against archons as such, but occurs in the unconscious where psychic factors that will save us are opposed by psychic factors that will condemn us. This battle of opposing psychic forces is portrayed symbolically in The Matrix in the final showdown between Neo and Agent Smith which begins in the underground (or subway), in other words, the unconscious. In the denouement of their confrontation, Neo charges headlong towards Agent Smith and dives at him; however, there is no collision, rather Neo merges into Agent Smith as if diving into a pool of water. A tumult brews within their entanglement before Agent Smith shatters like a shell, out of which a new Neo is born into light. In Jungian terms, the demiurgic ego dies and the Self is born into the light of consciousness. The experience of the Self is always a defeat for the ego, said Jung. In Gnostic terms, the pool of water represents the waters that exist below the firmament in which the conflict of human existence occurs. Like the light and dark brothers in The Gospel of Philip, Neo and Agent Smith dissolve into one another, finally. Agent Smith shatters like an empty husk, suggesting that the world of the archons is empty, false, nothing but an illusion, and only the Light remains.

* * *

PKD’s “message to the listening world” (2008, p. 246) was for us to awaken from our slumber and awaken to gnosis because our lives are in the balance. Like the ancient Gnostics—as well as Jung in his own fashion—PKD insisted that gnosis was the essential factor of salvation and, without it, salvation was not possible. Given his view that the universe is composed of information, he concluded that only information, the gnosis sought by the Gnostics, can save us: “There is no other road to salvation” (2001, p. 265, emphasis added). However, a key aspect of gnosis in PKD’s view is that the process of attaining gnosis is not the acquisition of something that we never had, but it is, in fact, the act of anamnesis (i.e., the loss of forgetfulness), in other words, the remembrance of who we are and where we have come from. He claims that the information that we need is here, covered up, and all we have to do is realise it (2011).

Salvation from what exactly? For PKD, it meant escape from this world, the Black Iron Prison. He claims that God is not responsible for “such a structure of suffering” (ibid., loc. 5775) but, instead, God wishes to liberate us from it and restore us “as part of him” (loc. 5775). A return to the original source is intrinsic to PKD’s gnosis. This concept of salvation, along with the notion of a counterfeit phenomenal world, is an inseparable part of his acosmic worldview and features in all of his writings. He adds that the objective he attempts through his written work is the eradication of this world, the achievement of which would go some way to our restoration in the Pleroma.

In a way similar to the Gnostic belief that the individual needed to initiate the process of salvation by preparing the bride to meet the bridegroom, PKD felt that the individual needed to “rebel” (loc. 6806), initially at least, against the Empire in order to instigate salvation. However, once again consistent with the view of the ancient Gnostics, PKD’s view was that gnosis on its own was insufficient for salvation, and that the role of the saviour was essential to restore us to our true state. On our own, we are unable to find the information necessary to escape from the morass of “drugs, communism, and sex and fake plural pathological pseudo worlds” (loc. 8339). Only from the Holy Spirit can we receive gnosis, hence the Christian teaching that we are saved by the grace of God rather than by good works. For PKD, gnosis from above, imparted by the Holy Spirit, resulting in a living plasmate in its cross-bonded, activated form (i.e., the homoplasmate), and accompanied by the sacraments, is the only means of salvation. According to PKD, the saviour draws us up and out of this world. Like the Gnostics before him, but in contrast to Jung, who held a far more world-affirming view, PKD surmised that the world itself cannot be saved, and that we need to be “rescued off this dying (toxic, stagnant) world” (loc. 8492). He summarises his metaphysics, and the saviour’s role in it, by stating that our minds have been deliberately occluded to blind us to the fact of our imprisonment. This prison is the work of “a power magician-like evil deity” (loc. 8339) who is being opposed by “a mysterious salvific entity which often takes trash forms, and who will restore our lost real memories” (loc. 8339). Yet, despite the dark brutality of PKD’s metaphors of the Empire and the Black Iron Prison, and the need to reject them in order to escape, the key to salvation is not to give in to what would be a natural urge to fight the system. In accord with Jung’s dictum that what we resist, persists, PKD thought that those who fight against the Empire become “infected by its derangement” (2001, p. 264), resulting in the paradox that, to the extent we defeat the Empire, we become the Empire. Sticking with the viral analogy, he notes that the Empire—the archons—spreads like a virus, imposing its nature on its enemies, and thereby takes control of its human hosts.

This brings to mind a scene from the standout Gnostic myth for modern times, The Matrix, in which Agent Smith shares an insight into the human condition. He claims that while trying to classify the human species he realises that they are not actually mammals. Every mammal in this world naturally develops an equilibrium with its habitat and forms part of the ecosystem. Humans, however, do not do this, notes Smith. Instead, humans migrate to an area and continue to multiply until all the earth’s resources in that area have been exhausted, forcing humans to relocate to another area and repeat the process. Smith adds, sarcastically, that the other organism that exhibits this behaviour is a virus. Smith concludes that humans are nothing more than a cancer on this planet, a plague that needs to be cured. I know he is the “bad guy”, but I cannot help liking Agent Smith, if only just a little bit. I have to give it to him, he has a valid point. We are the virus. We are the Empire and the Black Iron Prison. We are the jailed and our own jailers. We are the archons. However, paraphrasing George Orwell, all humans are archons, but some humans are more archonic than others. How does the body eliminate foreign pathogens? One method is phagocytosis, and although this is not the way the body deals with viruses—let’s not let a few medical details get in the way of a good story—it is interesting that PKD uses the analogy of phagocytosis as the means by which the homoplasmate rids the human of its archonic virus.

As noted above, Jung’s Gnostic vision involved a teleology at odds with the view of the ancient Gnostics. For the ancients, the created world had no positive purpose for either divinity or humanity. Its only purpose was a malevolent one: as an energy source for the parasitic archons who had created it. For Jung, the purpose of humanity in the world was the creation and expansion of consciousness. Like Jung, PKD’s Gnostic vision includes a constructive purpose for the world notwithstanding its counterfeit nature.

In the Tractates Cryptica Scriptura, PKD claims that the purpose the One Mind (Godhead) has for the universe is that it serves as a “teaching instrument” (2001, p. 266) for humanity. His acosmic Gnostic perspective leads him to believe that God is not revealed by the world as they have fundamentally different natures. In order to realise God, the world must be abolished. He likens the world to a mask projected by God in order to conceal himself from humanity. Humanity’s task, therefore, is to unravel the moral and epistemological puzzles that the world presents in order to “come to life” (2011, loc. 6968). For PKD, the created world is not isomorphic with the Godhead, the two are incompatible, with the world nothing but a “smokescreen” (loc. 6976) which humanity is to eschew rather than make peace with. The task of humanity in the world, therefore, is to learn or, more accurately, relearn how to become isomorphic with the Godhead, in other words, how to return to the original state of the Pleroma.

Like the Gnostics, PKD also couched the return to the Pleroma in terms of a vertical ascent via what he refers to as an orthogonal axis that will be discovered eventually and serendipitously, presumably after much hard work. Yet, once more in accord with the Gnostics, for PKD the ascent is purely metaphorical for, in reality, the attainment of gnosis means the rediscovery of something we already have. We are already in the Pleroma, we always have been and, rather than a physical ascent, the return involves a movement towards anamnesis and away from amnesia. So, rather than thinking that we have come from the Pleroma and will eventually return to it, it is more correct, according to PKD, to say, “I am part of [the Pleroma] now and always have been” (loc. 4565).

PKD’s notion of Gnostic salvation concerns not only the salvation of the individual, it also has a restorative value for the collective. Similar to Jung’s view that salvation through the growth of individual consciousness contributes to the collective growth in consciousness in which the Godhead comes to realise itself fully as God, PKD considered the salvation of the individual to have a far greater significance for the system as a whole than it did for the individual (2001). For the individual, gnosis, or anamnesis, results in “a quantum leap in perception, identity, cognition, understanding, world- and self-experience, including immortality” (p. 268). However, each person’s restoration contributes to the process of self-repair of the whole entity, the Pleroma.

Another factor in PKD’s concept of Gnostic salvation is the redemptive value of chaos as an impetus for change. In his paper, “How to build a universe that doesn’t fall apart in two days” (1978), PKD shares a secret that, in his writings, he likes to conceptualise universes that do, indeed, fall apart. He likes the mental stimulation of working through how the characters in his novels will cope with such universes. He confesses to a “secret love” of chaos and mischievously advocates more of it. He claims that order is not always a good thing as it tends to ossify and must, sooner or later, submit to change and the birth of the new. Before the new can be born, the old must perish and die. In the same way that Jung believed that the tension between the opposites was necessary for life, PKD realised that, out of necessity, a certain amount of chaos is required to counterbalance order and to precipitate the change. Chaos is “part of the script of life”. He continues that, difficult as it may be, unless we accept this need to change, we die inwardly, growth is stunted, and salvation, if not terminated, is suspended. Order and chaos are opposites which must be reconciled in life. Jung would concur.