In the preceding four chapters we have seen how after 1949 West German industry maneuvered more self-assuredly through the vagaries of economic and political reconstruction. Businessmen set up public relations organizations, they took part in the cultural and political discussions of the day, and they asserted themselves against perceived threats from organized labor. In short, industry assumed a confident and increasingly secure position in the young Federal Republic. Yet despite industrialists' growing optimism about their country’s future, the Nazi past maintained a powerful presence after 1949. It defined the parameters of political discourses, it served as the catalyst for industry’s image makeover, and it weighed heavily on the individual and collective psyches of West Germany’s social and economic elite. Industrialists, like other elites, saw the Nazi years as obstructing the path to West Germany’s psychic recovery. While they often attempted to ignore or navigate around this roadblock, they never abandoned their hopes of removing it entirely. Ironically, as the successes of German industry in domestic and international markets increased, businessmen became more aware of National Socialism’s persistence as a theme. As individual companies and business organizations branched outward, they brought into each new market a publicity apparatus that could influence not only the purchasing habits of foreign consumers and business partners but their attitudes toward West Germany and its past.

Nowhere was this pattern more evident than with respect to the United States. In the early 1950s German industrialists solicited the help of sections of the U.S. public both to engage with West Germany economically and to bury the “myth” of German industrial complicity with Adolf Hitler. In particular, America’s conservative intellectuals and business leaders rallied behind German industry in a demonstration of camaraderie and in a concerted effort to protect the capitalist West against the menace of collectivism at the height of the Cold War. These Americans saw themselves as part of an international milieu of businessmen and conservatives who understood one another and the necessities of the day. They drew on their pre-Hitler contacts, their affinities as “men of business,” and their professed disdain for Nazism in order to forgive German capitalism for any misdeeds in the service of the united struggle against totalitarianism.

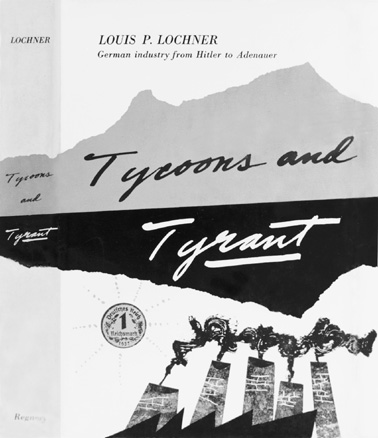

The first half of this chapter traces the developments in industry following the conviction of Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach and other businessmen in Nuremberg in 1948. Against the backdrop of rapid political and economic changes, most notably the formation of the ECSC and the Korean War, it follows the Krupp company’s attempts to secure the release of its managers from prison and to defend its reputation at home. The second half of this chapter focuses on West German industry’s attempt to ingratiate itself to an English-speaking public. In order to repair their image overseas, businessmen called on a number of prominent U.S. and British conservatives to plead the cause of West German industry. Their efforts culminated in an apologetic work by Louis Lochner, a prize-winning journalist who, in the words of one industry insider, was the “first person after the war to write for the purpose of saving the honor of German industrialists.”1

On 31 January 1951 U.S. High Commissioner for Germany John McCloy made an announcement that delighted the West German business community. After much deliberation McCloy had decided to grant amnesty to dozens of industrialists, politicians, doctors, and Nazi officials who had been found guilty in Nuremberg and who now sat in Landsberg prison.2 Among those affected by this sweeping declaration were Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, who had spent almost six years in detention and prison since his arrest, and eight of his colleagues on the Krupp board of directors. Friedrich Flick, the steel magnate convicted in a separate trial, had already been released in August 1950 for good behavior. By the mid-1950s Flick and Krupp had reclaimed their companies and personal holdings and had established a forceful presence on the political and economic scene. It is believed that they became the two richest men in Europe, in control of large empires of steelworks, shipyards, and manufacturing ventures. German industrialists' assurances to the contrary, the leading positions in German industry were again filled with people who had been deeply involved in the Nazi regime.3

The granting of clemency to industrialists and a number of other individuals convicted of war crimes is a familiar and still controversial theme. It has served both as the object of serious scholarship and as the centerpiece of more polemical attacks against Adenauer, the United States, and West Germany.4 It has been used as proof that denazification was badly flawed, as evidence of capitalism’s pervasive and pernicious force, and as a sign that the U.S. high commissioner was willing to coddle ex-Nazis. Most historians agree on a number of factors influencing the clemency decisions in 1951: the powerful effect that the Cold War exercised on U.S., and certainly McCloy’s, thinking; the desire to appease a German public highly critical of Nuremberg and the concept of collective guilt; and McCloy’s own belief that many of the sentences had been arbitrarily harsh.5 For whatever reasons, John McCloy did make it clear that the United States was willing to accept the rehabilitation of individuals with questionable personal pasts. The majority of West Germans approved of the commissioner’s decision, which they saw both as America’s acknowledgment of the “injustice” of Nuremberg and, even more so, as a sign that the United States now needed West Germany as a Cold War ally.6

Business leaders had not stood idly waiting for this encouraging moment. In the two and a half years separating the last Nuremberg convictions and the release of Krupp in 1951, industrialists were not only waxing philosophical about culture or shoring up their political position vis-à-vis the unions. These years were also marked by frenetic activity on the part of industry, and West German elites more generally, to reverse the effects of the Nuremberg trials. Dozens of industrialists, Nazi doctors, high-ranking politicians, and SS and military leaders were serving long prison terms or were awaiting the carrying out of their death sentences. With the founding of the FRG, the U.S. military government led by Gen. Lucius Clay was replaced by a civilian American administration under McCloy, who immediately faced loud demands to release the Landsberg prisoners and commute death sentences. In a conscious show of unity, industrialists, politicians, jurists, and church leaders came together to challenge the concept of collective guilt embodied in Nuremberg.7

One of their first steps after the final verdicts in 1949 was the establishment of a central Coordination Office to direct the campaign on behalf of the Landsberg prisoners. In the summer of 1949 Eduard Wahl, CDU politician and former legal counsel for the IG Farben defense team, founded what came to be known as the Heidelberger Juristenkreis (Heidelberg jurists' circle), which was mainly comprised of fellow Nuremberg defense attorneys and church leaders.8 Aside from preparing a document called the “Memorandum about the Necessity of a General Amnesty,” which called on the Americans to reconsider the imprisonment of industrialists and political and military leaders,9 the Heidelberger Juristenkreis also helped write and distribute, with the financial support of IG Farben, a 164-page document known as the Protestant Church’s War Criminal Memorandum (Kriegsverbrecher-Denkschrift der EKD). This and other documents made a favorable impression on McCloy, who began to question the wisdom of maintaining the retributive features of U.S. policy—as embodied in the Nuremberg prosecutions—while trying to build a trusting and cooperative relationship with the West German public.

While industrialists were contributing to the joint efforts on behalf of the convicted, they were also focusing on the specific circumstances of their imprisoned business colleagues. After the Krupp verdicts, for example, individual industrialists, companies, and business organizations sent numerous appeals to McCloy’s predecessor, Clay and, eventually, to the U.S. Supreme Court to reconsider the convictions. Neither, however, would countenance a reversal of the Nuremberg decisions.10

In light of these rebuffs, industrialists decided to focus not only on legal issues but on the physical and mental comfort of their imprisoned colleagues. In 1949, for example, the Association of German Steel Industry Employers (Verein deutscher Eisenhüttenleute) pressed the director of Landsberg prison to provide the inmates with some meaningful work with which to pass the time.11 The organization was able to secure some positive results: Krupp executive Eduard Houdremont was granted time off from physical labor to prepare the second edition of his book Manual on Special Steels Science,12 while Landsberg prison director Colonel Graham appointed another Krupp director, Fritz von Bülow, as his personal secretary and “letter writer.”13 In another show of solidarity, Hermann Reusch, chairman of the Association of German Steel Industry Employers, distributed a circular to his colleagues proposing that they “send more frequent letters to cheer up the gentlemen incarcerated in Landsberg prison.”14 This seemingly harmless request caused a small stir. A labor union representative got a copy of this memorandum and passed it on to the Office of the U.S. High Commissioner for Germany (HICOG), perhaps out of concern that Reusch was conspiring in some way with his colleagues. While there was nothing to these suspicions, the Americans found the documents quite illuminating. “The circular and minutes,” wrote a HICOG official, “are highly significant since they reveal that the Ruhr steel barons will identify themselves with those of their number which were convicted as Nazi offenders and shows [sic] they are still making an effort to keep the convicted Nazis within the innermost circle of the limited group which controls the powerful iron and steel industry.”15 This statement reveals inter alia the extent to which the U.S. government and the West German unions still had misgivings about German industry. They may have been ready to entrust the economy to Germany’s businessmen, but they were under no illusion that mentalities had changed overnight.16

In the opinion of a HICOG official, this document spoke volumes about Ruhr industrialists' intentions, yet it also had something to say about the state of U.S. and labor union attitudes in the early 1950s: clearly industry was not yet to be trusted, not even behind bars. This habitual distrust is further evidenced by a detailed U.S. State Department report from late 1951 that traced the political backgrounds of the leading men of heavy industry. The report was conducted in response to popular literature about former Nazis “getting back into power.”17 The study ranked current board members in the Ruhr as either former “active Nazis,” “nominal Nazis,” “non-Nazis,” or “anti-Nazis.” While the newer companies, with union members on their boards, fared well in the study, the report concluded that “a good number of the ‘bigger Nazis’ are still about and have by no means abandoned their interests in the industry.”18 Americans were prepared to hand over the reins of the economy to German industry, but not without reservations about the past behavior and present attitudes of its leaders.

While German industrialists were able to obtain some minor concessions regarding the treatment of the prisoners, their chief goal still remained the release of their colleagues. Their most potent strategy, therefore, entailed demonstrating that the law was on their side. If they could prove that the U.S. judges had committed legal errors, in both the establishment and the conduct of the war crimes tribunals, then business leaders could perhaps challenge the moral validity of Nuremberg and eventually secure the release of their men. Industry therefore relied less on emotional appeals, which were finding little sympathy among U.S. officials, and more on the fine points of international and American law.

In particular, lawyers and legal scholars outlined the case against the Krupp decision, which had resulted in the greatest number of guilty verdicts and which constituted the most visible challenge to the West German business establishment. Their arguments rested on the belief that the tribunal improperly relied on ex post facto law by applying U.S. jurisprudence to acts that had not been crimes on German soil. They also complained that, even when applying U.S. law, the judges refused to allow American lawyers to represent German defendants. In effect they forced German lawyers to learn U.S. jurisprudence overnight. These critiques also questioned the absence of legal precedents, disputed a host of procedural decisions by the judges, fumed over the January 1948 jailing of Krupp’s attorneys for contempt of court, and disputed the charges of slave labor and spoliation, which lawyers claimed had been committed by other countries during the war.19

Perhaps the most interesting and elaborate legal treatise originated from the Krupp firm. In the fall of 1949 Krupp defense attorney and Heidelberger Juristenkreis member Otto Kranzbühler prepared a short manuscript titled “Drei Amerikaner richten Krupp” [Three Americans convict Krupp], which argued against the Nuremberg verdict in familiar legal terms.20 When Tilo Freiherr von Wilmowsky, former deputy chairman (stellvertretender Vorsitzender) of the company’s supervisory board, read the piece, he persuaded Kranzbühler to expand it into a book-length work dealing with the issue of Krupp’s guilt or innocence.21 The study, they decided, would be reworked by a legal scholar but would bear the name of Wilmowsky, whose reputation, in sharp contrast to his company’s, had emerged from the Nazi years intact, if not enhanced.

For followers of the fate of German industry’s “royal family,” Wilmowsky was a familiar name. Best known as the uncle of Alfried Krupp by marriage, Baron Wilmowsky himself possessed an illustrious lineage. He was the grandson of Kaiser Wilhelm I’s last adviser, the son of a cabinet minister for Wilhelm II, and the husband of Barbara Krupp, whose father, Fritz, had headed the firm during its glory days during the Kaiserreich.

During the Nazi years Wilmowsky joined the Nazi Party, but as a devout Christian, conservative, and monarchist he had maintained links to the men who formed the underground resistance against Hitler. After the failed assassination attempt in July 1944, the Gestapo arrested Wilmowsky and prosecuted him for having consorted with the bomb plotters, as well as for criticizing the SS, for helping Jews to emigrate from Germany, and for patronizing the Lutheran Church. Although he had not, in fact, known beforehand about the assassination attempt, Wilmowsky was found guilty and was sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp with his wife, where the two remained until the end of the war.22

When Wilmowsky and Kranzbühler agreed to prepare a book, they realized that they would have to proceed cautiously. The Allies were at the time still considering breaking up the company, and neither man wanted to anger the people who controlled their fate. But they ultimately considered the book to be a proactive step that would clarify the peaceful nature of the firm without provoking the Americans. As a sign of this caution, they, besides designating Wilmowsky as author, changed the original provocative title to the less anti-American “Krupp, Victim of a Myth.” In order to convert Kranzbühler’s dry legal argument into readable prose, they also hired Ernst Rudolf Huber as a ghostwriter.23 Huber, in 1950 a professor of law at Freiburg University, had been a devoted Nazi and one of the leading National Socialist legal experts, having enshrined Hitler’s Führerprinzip in The Constitutional Law of the Greater German Reich.24 Krupp also called on the services of August Heinrichsbauer, lobbyist and erstwhile apologist for big business, to provide contacts within industry and to clarify historical details, especially about the company’s relationship to German rearmament in the 1920s and 1930s.25 Given Krupp’s attempts to avoid controversy at this stage, it is stunning that the firm would employ the services of two controversial figures, especially the Nazi scholar Huber. This perhaps testifies to industrialists' stubborn unwillingness to acknowledge how much damage their reputations had and could still suffer. But Krupp was aware enough of Huber’s controversial writings during the Nazi years to keep the ghostwriter entirely behind the scenes.

The book was completed in the spring of 1950, bearing its final revised title, Warum wurde Krupp verurteilt? [Why was Krupp convicted?], a phrasing that the company hoped would appear less polemical and thus more appealing to German and U.S. readers. The book began by drawing on the power of the resister defense carefully honed during Nuremberg. The preface reminded the readers that the “author” Wilmowsky had been an opponent and prisoner of the regime and thus had no stake in exonerating those truly guilty of atrocities. It then argued that from an American, German, “Christian,” and legal standpoint, the Krupp trial had been a disaster. The prosecution had turned Krupp and industry into a symbol of other people’s complicity, it had misapplied international law, and it had not recognized the impotence of industrialists in the total state, especially with regard to slave labor. In short, it had not understood that in Nazi Germany, “der Staat befiehlt der Wirtschaft” (the state commanded the economy).26 Finally, the book leveled a tu quoque charge: before blaming Krupp for having plundered and destroyed property, the Americans should have looked at their own policies during and after the war. The Morgenthau Plan, property confiscation, and dismantling were proof, argued the book, that the Americans were still caught up in a “war psychosis.”27

As evidenced by the letters to Wilmowsky, many segments of German society, especially the business world, welcomed the publication of Warum wurde Krupp verurteilt? The book gave readers an opportunity to express their rage against Nuremberg, an event that, in the words of one reader, was “worse than a crime.... It was an irreparable blunder.”28 Max Ilgner, defendant in the IG Farben case, expressed his regret that his own company had not written a similar book; perhaps Warum, he told Wilmowsky, would serve as a model for such an undertaking.29 Konrad Adenauer himself read the book thoroughly and passed on to Wilmowsky his opinion that Krupp had been gravely wronged; the chancellor gave his assurances that he would support the family and firm in any way possible in their quest for rehabilitation.30

Over the next two years, various plans to translate the book into English were also adopted but were ultimately abandoned. The German publication of Warum did, however, get some attention in the United States and England, particularly after Wilmowsky, with the assistance of the German General Consulate in New York, distributed free copies, along with an apologetic pamphlet written by Kranzbühler titled A Short Survey of the Krupp Trial, to businessmen, senators, publishers, university and public libraries, law schools, and political science and German departments.31 Some U.S. magazines and organizations did review the book favorably. The Federation of American Citizens of German Descent, not surprisingly, welcomed the appearance of a work that separated itself from the typically anti-German fare.32 The New Statesmen and Nation also gave a positive review to Wilmowsky. When in the next issue there appeared a letter to the editor criticizing this review—citing industry’s shameful use of slave labor—Wilmowsky wrote his own editorial, outlining in detail his arrest and imprisonment in the “notorious concentration camp Sachsenhausen” and insisting that “the use of POWs and foreign workers was the sad but unavoidable result of a total mass war.”33

Like most public relations projects, Warum wurde Krupp verurteilt? was designed to appeal to both a German and an American public, as well as to company employees and unionized workers in West Germany who still harbored suspicions of big business.34 Its most important aim, however, was to secure the release of imprisoned Krupp officials. In this regard, Krupp directors received encouraging news as they were making the final revisions to the book in March. High Commissioner McCloy announced the formation of a clemency board to review the sentences handed down in Nuremberg.35 The Advisory Board on Clemency for War Criminals (also known as the Peck Panel, after chairman David W. Peck, a New York Supreme Court justice) was slated to consider the Krupp case in June, after which it would offer recommendations to McCloy about possibly commuting sentences or granting amnesty.36 Wilmowsky spoke with his imprisoned nephew and his lawyers, and they decided that by hurrying the publication of Warum, they might in fact influence the three-man clemency board in favor of Alfried.37 But the book’s author wondered in private whether his legal treatise would have such a salutary effect. Declared ghostwriter Huber,

I cannot begin to guess how the American side will receive this book. I do, however, believe that, as it stands, it avoids wording that could in any way be interpreted as a challenge. Certainly the danger exists that certain groups in America will denounce any criticism from Germany as a symptom of a much ballyhooed German “nationalism.”... Yet it is equally our task to speak up for what we with good conscience believe is right and just, even if one tries to avoid... polemics. I am not without hope that our piece will have a positive effect on the Clemency Board.38

In June 1950 Warum wurde Krupp verurteilt? reached the Peck Panel just as it took up Alfried Krupp’s case.39 It is not, however, known if the three Americans ever read the book—or if they could read German at all. But that hardly seemed to matter. The book would soon spawn a larger transatlantic project on behalf of West German industry. Moreover, within two months the clemency panel would issue recommendations to Commissioner McCloy that were very favorable to the Landsberg prisoners. However, two other events preceding the announcement that summer did more to influence U.S. attitudes about German industry than this self-serving legal treatise. The first was the unveiling of the Schuman Plan in May 1950, and the second was the outbreak of the Korean War.

The Schuman Plan, named after French foreign minister Robert Schuman, was the culmination of a multiyear Allied discussion about the fate of German heavy industry.40 Various plans had ranged from deconcentration to nationalization to internationalization to the establishment of a customs union between France and West Germany. The plan eventually ratified in April 1951 created the ECSC, in essence a pooling agreement between heavy industry in France, West Germany, Italy, and the Benelux countries. A jointly administered “high authority” in Luxembourg was made responsible for regulating and coordinating the production and export of six countries' coal and steel. The Coal and Steel Community did not become a giant European steel cartel that divvied up markets and fixed prices. Rather, it lifted tariffs while, in effect, leveling the playing field for French heavy industry, which had long been overshadowed by the Ruhr.

Most of West German industry threw its support behind the Schuman Plan, which, to the Americans, was a hopeful sign that German industry was now committed to peaceful competition and cooperation with its neighbors. For their part, when faced with the choice of dissolution and liquidation or existence within a regulated community, industrialists happily chose the latter. Yet a week after the announcement of the plan, German industry learned some bad news. The Allies unveiled Law No. 27, which called for the liquidation and recombination of the Ruhr’s largest companies and which controlled the steel output of each company. As much as Western policy makers had delighted in the show of solidarity around the Schuman Plan, they would not abandon their intention to break the traditional power of German heavy industry. Industrialists bitterly resented Law No. 27, primarily on the grounds that it went against the spirit of the Schuman Plan, which called for the revival, not the destruction, of German industry.41

If these two proposals appear contradictory, they nonetheless reflected the Allies' ambivalence about the revival of the West German economy. On one hand, the United States, France, and Britain wanted to welcome industry into a community of democratic economies. The Ruhr would again produce for Europe and the world. On the other hand, Germany had once proven itself incapable of adhering to the standards of international cooperation and peace, and the Allies were not going to pretend they had forgotten about Hitler’s aggressive imperialist aims. High Commissioner McCloy did not disguise this ambivalence when on 16 June 1950 he spoke to a group of fifty Ruhr industrialists and bankers in Düsseldorf about U.S. views of West German business. With events moving rapidly in the Ruhr, this was to be McCloy’s “state of the union” speech to industry, perhaps the most significant address to Germany’s businessmen since the end of the war. McCloy began by congratulating industry on West Germany’s rapid recovery since the Marshall Plan and the currency reform. (Industrial output, according to McCloy, had reached 104 percent of its 1936 levels).42 Despite such cause for celebration, McCloy warned his listeners to avoid complacency. Unemployment was still high, the country depended on foreign aid, exports lagged far behind imports, and investment needed to increase. In reference to the burgeoning Osthandel (trade with Eastern bloc countries) and U.S. fears about German economic relations with the Soviet bloc, McCloy reminded the audience that West German trade lay “not in the East but in the West.” Finally, West German industry, McCloy argued, still faced a major psychological barrier:

To be perfectly frank, this development [the revival of the Ruhr] causes serious doubts in the minds of many people. For many other countries, the Ruhr is a symbol of industrial capacity devoted to aggression and its rebuilding creates concern for their security. Looking at the past, they wonder whether these factories and foundries will be used in the future for peace or for aggression.... For Germany itself, the re-growth of industry is certain to raise serious questions. Many Germans are concerned lest their economy be dominated again by a small group who will use their concentrated power to control German political and social life. The question is: will the men managing the industries of the Ruhr use their influence to support a liberal, democratic German state? Or will they use it to stifle progressive elements and to aid men and policies that in the past led Germany to destruction and have caused so much misery in the world? In short, Ruhr industry faces the task of winning the confidence of the German people and the people of the world. You and others like you, therefore, have a tremendous opportunity and responsibility. Your actions and your attitudes can ensure that the resources of German industry are dedicated to a new and peaceful development of Europe; your actions can contribute greatly to the creation of a genuinely democratic society and state in Germany.43

Commissioner McCloy’s speech was a notably blunt commentary on the challenges facing West German industry. While it acknowledged the many problems German business faced, with respect to both its economy and its international image, it was tactful and restrained, especially when broaching the issue of German business guilt. Clearly, whatever McCloy felt about German industry’s relationship to Hitler, he would not let it come to the surface or mute his overall optimism. His audience seemed unruffled by his admonitions, expressing enthusiasm for the Schuman Plan and gratitude for the support the United States had shown. Yet certain observers were secretly fearful. Much of the old guard still resented Washington’s punitive treatment of German industry, both its prosecution of business leaders and its steering the economy so dramatically away from a cartel tradition that they still cherished.

These lingering resentments came to the surface during the question-and-answer period after McCloy’s speech, when Theo Goldschmidt, president of the IHK Essen and a fierce defender of Ruhr interests, stood up to complain about excessive taxes and the high cost of absorbing refugees from the East. The mood in the room quickly changed. An animated McCloy jettisoned his rhetorical caution and angrily chastised Goldschmidt for harping on U.S. “failures.”

Don’t forget that America’s high taxes are the result of German aggression. Don’t forget who started this war. Whether or not you gentlemen here are responsible personally for it, remember the war and all the misery that followed it—including your own—was born and bred in German soil and you must accept the responsibility.... Why didn’t you mention the Marshall Plan? Why didn’t you mention the aid we are giving the refugees while you stall? Why don’t you recall how the occupied countries lived under your occupation? ... Don’t weep in your beer. Think of the good things as they come to you.44

A chastened Goldschmidt took his seat, while a hush descended over the room. Then resounding applause followed. The Ruhr elite, out of either shock or politeness, seemed to be countenancing the condemnation of their influential colleague.

What is so interesting about this speech—and its dramatic end—is that it reflects all the tensions and contradictions in the U.S. view of West German industry. It was at once cordial and upbeat, suspicious and accusatory. But it also made clear that there was no turning back or giving in to the antibusiness sentiments expressed by some members of the U.S. and West German public. His doubts notwithstanding, John McCloy saw West German industry as the best hope for a peaceful and prosperous Europe. But it had to be contained within a democratic system of checks and balances and constantly reminded of its compromised past.

Whatever lingering doubts McCloy had about the revival of the Ruhr were greatly tested when, nine days after his speech in Düsseldorf, North Korean troops crossed the thirty-eighth parallel and entered South Korea. Throughout the West the outbreak of the Korean War unleashed a sense of panic. There was talk of communist agitation in West Germany and Russian troop concentrations on the East German border. Rumors circulated about food rationing and the flight of U.S. military personnel from Germany. Stories spread of the rapid remilitarization of West Germany, the revival of the army, and the reactivation of Wehrmacht generals and officers.45 In light of such concerns, the Korean War seemed to bode ill for industry. It restored negative memories of an aggressive military and economic powerhouse, and it fed into the emerging debate in 1950 on the rearmament of West Germany. At a time when they were trying to regain the trust of the world, industrialists did not readily welcome images of tanks rolling off the Krupp assembly lines and German rockets flying eastward.46

In fact, however, the Korean War had more positive than negative implications for German industry. For one, it increased demand in the West for raw materials and finished goods to support the war effort. West German industrial output increased, and a new phase of economic growth was initiated. Both as a response to war demands and as a gesture to industry in the quest to get the Schuman Plan ratified, the Allies announced in October 1950 that they had lifted their limitations on steel production. The war thus seemed to be ushering West Germany and its economy fully into the Western fold. On a psychological level, too, the Korean War did not simply stir up old fears about German industrial and military might; it also seemed to provide evidence of what industrialists had taken great pains to prove: that they were indispensable in the fight against communism.47 For their part, German industrialists, given the accusations about past complicity, were always extremely cautious about publicly supporting the rearmament of West Germany. The debate over rearmament was accompanied by public demands for the release of military leaders still in prison, and given the explosiveness of this theme, industrialists were wise to stay as far from this debate as possible. On the rare occasion that they entered the fray, business spokesmen like Fritz Berg and industrial publications consistently forswore any urge among industrialists to expand their businesses into military contracting.48

The Korean War and the Schuman Plan provided industrialists with a difficult choice with respect to lobbying for the amnesty of their colleagues. Either they could step up their campaign on behalf of the convicted industrialists while international events were going their way, or they could soft-pedal in anticipation of a positive announcement by the clemency board. In effect, the events of the summer of 1950 forced industry to decide in which direction to take its public relations. Those who subscribed to more vigilant tactics argued that industry should draw up a new set of resolutions regarding the Nuremberg judgments and continue to push its legal case vigorously. But Otto Kranzbühler, who seemed to be calling the shots, rejected this idea. Industry had bombarded the Americans enough, and now it would be better to employ more indirect means. He saw one such opportunity at the church congress (Kirchentag) to be held in Essen in late August, where a captive audience of local workers and sympathetic clergymen planned to pay homage to the city and its chief employer, Krupp. It was to be a show of solidarity by Germany’s employees and managers. In anticipation, Kranzbühler contacted the event coordinators and asked that the speakers, such as Hanover’s bishop Hanns Lilje, highlight the firm’s history of social achievements and, in particular, the fact that there had never been a strike at Krupp. He also asked the speakers to link the imprisonment of Alfried Krupp to the most controversial topic of the day: industrial codetermination. Both, argued Kranzbühler, posed a grave threat to the morale of the Essen workers and, thus, the productivity of the Ruhr.49 By linking Alfried Krupp’s imprisonment to the ostensibly more political issue of codetermination, Kranzbühler was cleverly manipulating the sentiments of the workers, who were sympathetic to their imprisoned owner’s cause while, at the same time, taking advantage of the anticodetermination sentiments of a number of occupation officials.

On 25 August the Beauftragte für das Evangelische Männerwerk des Kirchenkreises Essen sponsored its gathering. The speakers dutifully portrayed Alfried Krupp as a provider and protector against the dangerous influence of “the masses.” In a talk titled “Man in the Collective,” one speaker quoted the imprisoned Krupp verbatim: “I am saying this for the whole world to hear: there is in Essen a mass—tens of thousands of Kruppianer. But these Kruppianer are not mass men. And we will do everything to make sure that they do not gradually become mass men through privation, and that the large family of Kruppianer will reunite for the peaceful work of reconstruction—the family of Kruppianer with the Krupp family.”50

Three days after these words were uttered, the “Krupp family” received the news it had been waiting for. The Advisory Board on Clemency for War Criminals had submitted its report, and it was the panel’s conclusion that Alfried Krupp’s sentence and the confiscation of his personal fortune and industrial holdings were unduly harsh in light of the decisions against other industrialists. The panel recommended a reduction of his sentence and the return of his property. It made no recommendations on the IG Farben and Flick defendants, as they were soon to be released for good behavior.

While the Peck Panel’s decisions have often been portrayed as an overly solicitous gesture to West German elites, they did not let the Landsberg defendants off the hook entirely. As Thomas Schwartz has written, the panel “sought to appease all sides by combining a strong defense of the Nuremberg principles with a wide-ranging leniency.”51 It did not challenge, for example, the thesis presented at Nuremberg that institutions and professions—the SS, industry, and doctors—had conspired to realize National Socialism’s aims. Nor did it accept the defense’s arguments about the impropriety of U.S. law in a German context. But when it came to individual cases, the panel did believe that many of the men who were now imprisoned had possessed a relatively low position in the Nazi government or corporate hierarchy and that the sentences had been applied unevenly.

McCloy was not obligated to accept these recommendations, but he ultimately did so, both out of conviction and for practical reasons. On 31 January 1951 he announced that he was releasing the industrialists and dozens of other prisoners convicted in the Nuremberg trials.52 He returned Alfried Krupp’s property and holdings on the grounds that their confiscation was “generally repugnant to American concepts of justice.”53 On 3 February West German industry breathed a sigh of relief as the prisoners left Landsberg and returned home. While the public and political debates over the amnesty for other prisoners would continue through the 1950s, for industry the Nuremberg nightmare seemed to be over.

In granting amnesty to Krupp and his colleagues, McCloy, as Schwartz has rightly argued, grossly underestimated the extent to which industry had been involved in Nazi crimes. For example, he bought into industry’s incorrect claim that Alfried Krupp was a lowly official tried in lieu of his sick father, Gustav, and he also accepted too readily the defense’s contention that companies had been forced to use slave labor. Critics of McCloy’s decision have long assumed that the Korean War and the desire to rearm Germany against the communists induced McCloy to free the “capitalists” and put them back to work. But McCloy, while indeed a staunch anticommunist, vehemently denied that Korea, the Cold War, and the rearmament debates had anything to do with the release of Krupp.54 His decision was, he insisted, based solely on legal and humanitarian considerations. There is indeed no direct evidence that the debates in 1950 over remilitarization and the public pressure for the release of military officers influenced McCloy’s decisions regarding industrialists. But Korea and the rapidly escalating tensions with the Soviet Union had certainly fostered hysteria about the security of Western Europe that could only have worked to the industrialists' advantage. Whether or not he would concede as much, John McCloy was responding to the political mood of the day, which saw little use in perpetuating a punitive relationship to Germany during the Cold War. McCloy felt that the fight against Soviet communism demanded Western unity, industrial strength, and eventually West German participation in an Atlantic defense force.

The immediate aftermath of Krupp’s release is an oft-told story. The British press was outraged, while West Germans were ecstatic over McCloy’s decision. “The liberation of Alfried Krupp,” wrote a VSt director to McCloy, “has rejoiced our economic leaders.”55 The now notorious photos of Alfried Krupp hosting a celebratory champagne brunch after his release unleashed a furious response among international observers as well as U.S. occupation officials, who bristled at this tasteless display of self-indulgence following their gesture of goodwill. In reality the Krupp firm itself had not planned this champagne breakfast. It was an unexpected and unrequested gift from the hotel to which Krupp retired after his release. The Krupp management itself was furious and probably predicted a negative U.S. reaction. The Americans were indeed so unsettled that they sent Günter Henle to investigate this public relations blunder. Wrote a HICOG employee to Henle,

It was unfortunate that this publicity was attached to Mr. Krupp’s departure from Landsberg. Such are the incidents which create a bad atmosphere, although they are of course not intentional. Somewhere, somehow, something went wrong and Mr. Krupp was badly advised. That such matters can be handled in a discreet manner without publicity is proven by the discharge of Mr. Flick, who left Landsberg practically unnoticed and whose name has been kept out of the public limelight ever since. However, the less said about this matter from here on will be the best for all concerned.56

The Krupp fiasco was one more reminder of the Western Allies' lingering suspicions of German big business. To be sure, since the end of World War II, the Allies had been offering mixed signals about their willingness to countenance assertiveness on the part of Germany’s businessmen. Occasionally they would allow a public relations initiative or a self-promoting measure, but they were easily angered by any show of disrespect or tactlessness by the vanquished. Clearly, postwar industrial recovery involved a series of gambles and tests, and West Germany’s economic elites would still have to proceed with caution if they were to regain the complete trust of the Allies.

Six years had passed since the end of the war, and industry had made many strides in its attempt to secure a new legitimacy in the eyes of the Western Allies and the West German public. Yet memories of industrial behavior and, more importantly, actual mentalities within industry could not disappear or transform themselves overnight. Most company leaders had joined the Nazi Party and had supported, tacitly or actively, the Nazis' economic aims, and this the Americans would not easily forget.57 Yet despite lingering concerns, by the beginning of 1951 the United States also made it clear that it was on the side of West German industry. Industry now had to reckon with a tougher customer, one that held even more power over the future of German industry: the American public.

After the release of the Landsberg prisoners at the beginning of 1951, West German industry faced important decisions about how to approach the lingering issue of corporate guilt under Nazism. Most industrialists felt that the fight against the “myth” of business complicity should continue. The attacks on German industry were still occurring, and they were coming not only from the labor unions and the East German press but from across the English Channel and the Atlantic in a spate of scholarly and popular works about Germany. In the words of a VSt official in 1950, the chief culprit was America’s implicitly Jewish “immigrants,” who were perpetuating the view “that Ruhr industry was of the same heart and mind as the NSDAP.”58 It is not clear to which immigrants he was referring, but the 1950s had indeed begun with a number of books in English calling attention to the past and present situation of German industry. In 1950 James Stewart Martin, the former head of the Decartelization Branch of the U.S. Military Government, published All Honorable Men, which narrated in extremely disgruntled terms the author’s vain efforts to prevent German industry from regaining its pre-1945 strength. Martin drew on the familiar theme that the Nazis' rise and consolidation of power was the handiwork of big business and that industry’s postwar resistance to change signaled the endurance of Nazi mentalities. In 1950 West German industrialists read Martin’s book with great curiosity about the “mentality of the American deconcentration fanatics,” as well as with considerable concern about Martin’s “destructive judgments about German industry.”59 They passed the book on to one another and compiled lists of specific passages that could in any way be damaging to their interests.60

All Honorable Men was just one of dozens of books from the early 1950s that criticized the “return to power” of industrialists and militarists.61 Despite a stream of critical publications, German industrialists were encouraged by the appearance of a few books that resisted the more damning clichés about industry. They took heart at the publication of Norman J. G. Pounds’s The Ruhr, which according to Tilo Wilmowsky, avoided the trap of blaming German industrialists for Hitler.62 They also passed around other books that criticized U.S. occupation policies more generally. Victor Gollancz, the British reconciliationist publisher, wrote In Darkest Germany about his visit to a mal-nourished and disease-ridden Germany in 1946.63 The book displayed photographs of sick and emaciated Germans, thus drawing an implicit comparison between the fate of Germans under the occupation and that of Germany’s victims before 1945. Other books espousing an open sympathy for Germany were U.S. conservative Freda Utley’s High Cost of Vengeance, Montgomery Belgion’s Victors' Justice, and Lord Maurice Pascal Alers Hankey’s Politics, Trials, and Errors —all damning assessments of the American occupation, its war trials program, and its industrial and food policies in West Germany.64 These books were not best-sellers. But they represented a unified voice of dissent at a time when most literature was overwhelmingly critical of Germany. More importantly, they were all, with the exception of Pounds’s book, issued by a single U.S. publisher, Henry Regnery, who took upon himself the task of representing what he saw as a downtrodden and unfairly maligned nation. Regnery was one of postwar America’s most important conservative voices and the sponsor of West German industry’s definitive answer to its critics.

Through Regnery we can witness the emergence of a conservative intellectual sensibility that stretched across the Atlantic and encompassed social and economic elites in Western Europe and the United States. The descendant of German Catholic farmers in Wisconsin, the son of a Chicago textile magnate, an exchange student in Nazi Germany, and a former student of economist Joseph Schumpeter at Harvard, Regnery seemed almost naturally predisposed toward German business. After writing a number of articles critical of the Democratic Party and its punitive policies toward Germany, Regnery inaugurated his own publishing company in the late 1940s with three books that foreshadowed a lifelong preoccupation with Germany. Next to the Utley, Gollancz, and Belgion publications, three of his earliest titles, Regnery also published Hans Rothfels’s The German Opposition to Hitler and, later, an array of works by prominent German conservatives such as Ernst Jünger, Friedrich Georg Jünger, Konrad Adenauer, and neoliberal economist Wilhelm Röpke, who would become a regular foreign contributor to the National Review in the mid-1950s.65 Despite Regnery’s interest in Germany, his most famous “discoveries” were William F. Buckley Jr., whose first book, God and Man at Yale, lashed out at liberal academic elites and their failure to inculcate a spirit of Christian individualism in their students, and Russell Kirk, whose The Conservative Mind became the bible of postwar U.S. conservatism.66 By 1950, when German industry learned of him, Regnery had established himself as America’s foremost conservative publisher who, in the words of Krupp attorney Otto Kranzbühler, also published German-friendly books “as a hobby.”67

Regnery’s connection to West German industry began with a letter from Tilo von Wilmowsky. In June 1950 Alfried Krupp’s uncle asked Henry Regnery to publish an English translation of Warum wurde Krupp verurteilt?68 Regnery rejected the book on the grounds that it would not sell well in translation, but he did express his support for a project that would take on the Nuremberg trials and the thesis of big business guilt more generally. Wilmowsky, while disappointed with the rejection of “his” book, was in fact already drawing up plans for a more exhaustive study of the Nuremberg industrialist trials and the behavior of German industry during the Nazi years.69 As we have seen, industry had taken on such projects before. But this, in its final form, would be different. It would be written in English, it would be widely distributed, and it would carry the weight of two continents and numerous influential backers and advisers, most notably Krupp and Regnery.

From the time of the project’s inception until its publication in 1954 in the form of Louis Lochner’s Tycoons and Tyrant, four years would pass. During this period Wilmowsky gathered around him some of the most influential names in West German politics, as well as an impressive list of supportive Americans. Some of the more prominent names are worth mentioning. Former German chancellor Heinrich Brüning, who in 1950 was winding down an eleven-year teaching stint at Harvard in preparation for a move to the University of Cologne, was privy to the project from the outset.70 Brüning’s successor as chancellor in 1932, Franz von Papen, who had recently been released from prison and whose autobiography was, at the time, selling well, also offered his assistance.71 From the world of German politics there was, finally, Herbert von Dirksen, the former German ambassador to Moscow, Tokyo, and London, who used his old connections to secure support among pro-German Britons for a study that, in Wilmowsky’s words, would clear the “rubble” in industry’s way.72

When Wilmowsky broached his latest book idea to his friends and colleagues, he encountered, as had become usual, a mixture of support and concern about the project’s scope and timing. Rather than doing a study on the guilt or innocence of German industry, Dirksen suggested, it would be “psychologically better” to commission a “neutral investigation of industrialists in the total state and in total war.”73 The head of the Siemens archive echoed these reservations: “Would it not be timely to follow [the Wilmowsky book] with a more general investigation into the political activities and influences of industry in this era and in different countries?”74 Clearly both men had in mind a comparative history of the Nazi and Allied economies during World War II. If they could reveal industry/state cooperation as a universal phenomenon during times of war, then the behavior of Germany’s industrialists—fulfilling arms contracts, employing POWs and forced labor, and plundering—would, they hoped, be relativized and perhaps even humanized. The behavior of German business would no longer be considered sui generis but, rather, the expression of a universal readiness to support one’s country while its citizens were fighting and dying at the front. Moreover, with the announcement of the Schuman Plan, Dirksen felt such a book would be politically expedient.75 What better moment, when the eyes of the world were on German industry, to prove itself worthy of international trust and put an end to the “Nuremberg Complex”?76

Heinrich Brüning, in contrast, expressed doubts about whether the time was ripe for an English publication, especially when things were going better for big business. Montgomery Belgion, in response to Dirksen’s suggestions, doubted that the English-speaking public paid any attention to the Schuman Plan, let alone German business. “My own feeling,” he wrote to Dirksen, “is that such a book ... would not appeal to the general public unless it could be cast in the form of a dramatic story, and that would require on the part of the author a rare combination of gifts—an understanding of the problems of large-scale business and also an ability to give the exposition of them a kind of magic touch. I do not myself know of any English or American writer who possesses that combination.”77

Most of Wilmowsky’s colleagues within German industry were doubtful at first. They remembered well the brisk beginnings and abrupt endings to earlier projects defending industry. Flick officials were especially wary of such an undertaking. In June 1950 their boss was still in prison, and Friedrich Flick personally expressed a fear that a book about industry would jeopardize his tenuous position with the Allies, who were considering his early release. Another opponent of the project was Hermann Reusch, who had been so active in the Heinrichsbauer apology in 1948. Only a publication in Time or Life magazine, the GHH director argued, would reach enough readers to have any effect.78 Finally, Wolfgang Pohle, the former legal counsel for Flick, was leery of another venture into the publicity unknown. He recalled his own aborted efforts with Heinrichsbauer and a more recent attempt by honorary professor Kurt Hesse of the Frankfurt Academy for World Trade to write about the industry trials.79 After spending two nights reading through Hesse’s finished manuscript with representatives of the Klöckner company, Pohle determined that the work had to be entirely rewritten. The project was eventually declared an “absolute failure” (absoluter Mißerfolg) and abandoned entirely.80 Finally there was the problem of funding. Allied Law No. 27 held the iron and steel companies of the Ruhr in a state of liquidation, and this made obtaining funding from heavy industry an extremely difficult process, one that demanded constant circumspection and humble solicitation of the authorities. Any new project, wrote Pohle, would therefore have to rely heavily on funds from the chemical and the machine tools industries, which controlled their own financial fates.81

As in the past, however, doubts gave way to cautious support. As the events of the summer of 1950 played out, business leaders detected a friendlier climate for an investigation into the “defamation of business” (Wirtschafts-Diffamierung).82 In June the Allies had opened the West German economy to overseas investment. In August the clemency board had made its recommendations regarding Krupp, and Friedrich Flick had been released from prison. Finally Wilmowsky’s primary contact in the United States, former editor of the Berliner Tageblatt and Regnery copyeditor Paul Scheffer, predicted enthusiasm in the U.S. business community.83 With the support of the Americans, the project might indeed have a chance. That summer the battle lines were being drawn in the codetermination debate, and industry could use the support of U.S. business, which found codetermination anathema to its own labor traditions and principles. By February 1951, when Krupp was released from prison, Wilmowsky could happily report that the four companies tried for war crimes (IG Farben, Krupp, Flick, and Röchling) all supported his idea.84

Despite the now unified support of West German business, two essential ingredients were still missing: an author and a publisher. As to the latter, Montgomery Belgion had been doing some footwork. He spoke with the head of the University of Chicago Press, who welcomed the project in principle but feared low sales. Despite his rejection, the editor did express his willingness to help find a writer and perhaps defray some of the book’s expenses. Belgion also turned to Yale University Press, whose editor was Eugene Davidson, a Germany specialist and editor on the board of the conservative journal Human Events with Regnery.85 Davidson reported encouraging words from the university’s economics department, as well as his own belief that while it would not sell well to the mass public, a study of the war economy would find great support in academic circles. This conception of the book differed markedly from that of Wilmowsky, who had envisioned the book not as a piece of dispassionate scholarship per se but as a potential best-seller.86 If the book was supposed to reach as broad an audience as possible, somebody who wrote in a popular style was needed. Given these sentiments, it should not be surprising that Wilmowsky held the more suitable Henry Regnery in reserve should Yale withdraw its support.

A year had passed since its inception, and the project was moving slowly forward. But it still needed an author. Wilmowsky solicited the advice of Marion Gräfin Dönhoff, a descendent of an old Prussian noble family with an anti-Nazi record, a journalist on the liberal Die Zeit, and an occasional contributor to Human Events.87 Dönhoff was unable to come up with any authors. At IG Farben’s request, Wilmowsky then offered Montgomery Belgion the job, but the latter demurred, preferring to continue serving as a project adviser rather than author.88 Over the course of 1950 and 1951 the list of potential authors grew to include some of the most prominent (mostly conservative) names in U.S., British, and German letters: Allen Dulles, former Office of Strategic Services representative in Switzerland with connections to Germany, soon to be named director of the Central Intelligence Agency, and author of a 1947 book on the anti-Nazi resistance, Germany’s Underground;89 novelist and erstwhile big business critic Sinclair Lewis; Harry Elmer Barnes, formerly of the revisionist school of U.S. history during the 1920s; Götz Briefs, an émigré social scientist teaching at the New School for Social Research; Arnold Wolfers, former president of the Politische Hochschule in Berlin until 1933 and professor at Yale; Armin Mohler, a conservative young Swiss writer whose dissertation, “Die Konservative Gegen-Revolution, 1819–1933,” had just been published by Warum publisher Friedrich Vorwerk;90 Vivian Stranders, professor at the University of London and publisher of the anti-Soviet The Bulwark in London;91 and finally William Henry Chamberlin, historian of Russia, former correspondent in Moscow, and author of the virulently anticommunist America’s Second Crusade, which Henry Regnery published in 1950 as his “first revisionist work.”92

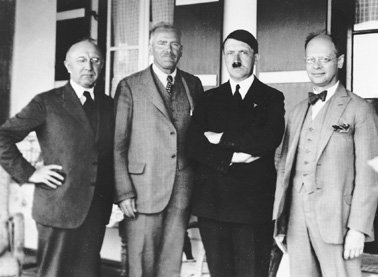

Louis Lochner and two other U.S. correspondents interview Adolf Hitler in Berchtesgaden, Bavaria, 1932. Lochner is on the far right. (X3, 20669, courtesy of State Historical Society of Wisconsin)

None of these authors worked out, and after a long and fruitless search, Wilmowsky and Scheffer finally came up with the name of Louis Lochner. Lochner was a journalist who had just edited and written the introduction to Regnery’s newest publication, the memoirs of Lochner’s close friend and confidante Prince Louis Ferdinand of Hohenzollern, who aside from being the grandson of Kaiser Wilhelm II and would-be heir to the German throne, had worked as a mechanic at Ford’s Michigan plant in the early 1930s.93 Lochner, however, had even stronger credentials than his friendship with a royal scion. He was a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, a pacifist, an expert on Germany, and a proven business advocate. He was the editor of Joseph Goebbels’s diaries and a biographer of Henry Ford, of the violinist Fritz Kreisler, and, later, of Herbert Hoover.94 As head of Berlin’s Associated Press office in the 1930s, Lochner had closely followed the rise of Hitler and the consolidation of his regime. For a time he had even been held in a Nazi detention camp and had, like Wilmowsky, maintained close ties with the men who were later murdered following the July 1944 plot against Hitler.95 An anti-Nazi fluent in German, staunchly anticommunist, and friendly with some of the most prominent figures in German public life, Lochner seemed perfect for the job.96 Regnery rightly predicted that Lochner would grab at a chance to be of service to his old contacts in the German political and economic establishment. “Standing before me is the greatest challenge of my not entirely uneventful life!” wrote an excited Lochner to Wilmowsky upon accepting the latter’s formal offer to write the book.97 Wilmowsky had found his author. When Yale learned that Lochner and not one of their own economics professors had been offered the book, they withdrew their support. The project was now squarely in Regnery’s hands.

The next step was to secure funding. Regnery and Wilmowsky originally considered turning solely to U.S. backers, such as foundations or private philanthropists. Eugene Davidson had recommended the Social Science Research Council,98 while Robert Hutchins, the recently retired chancellor of the University of Chicago, suggested that Regnery speak with the Ford Foundation, an organization that Hutchins served as adviser on German matters.99 While the Ford Foundation would never underwrite a publisher, suggested Hutchins, it might indeed grant a fellowship to the Foundation for Foreign Affairs, which Regnery and Eugene Davidson codirected in Washington. The latter foundation, Hutchins pointed out, could then forward funds to Regnery and Lochner.

Lochner and Regnery were dissatisfied with these options. It would take at least six months to get a decision from the Ford Foundation, and Lochner was eager to start on the project immediately. They therefore turned instead to the people who had the most to gain from this project: West Germany’s industrialists. In October Alfried Krupp met with his lawyers to discuss the feasibility of his firm’s funding part of the Lochner project. After much discussion they decided that Krupp would give an initial advance of $10,000 to the project, which Regnery would eventually pay back from the book’s royalties, and a $6,000 travel account for Lochner after his arrival in Germany. All this, however, was made contingent on other West German companies pitching in. Krupp asked Theo Goldschmidt to solicit other firms for contributions. Over the course of the next year, and with the active involvement of the DI and the BDI, Krupp managed to raise the appropriate funds.100 In March 1952, a few months before Lochner’s arrival in Germany, Kranzbühler received the approval of the economics ministry in Bonn for the transfer of funds to Regnery.101

These arrangements, even though approved by Bonn, were not risk free. Wilmowsky warned that while the impetus and much of the money was coming from German industry, all parties involved must pretend that the project had originated in the United States. “We must find a way to avoid any impression that the book is a plea financed by the German side. We do have certain reservations about making an official contribution to the publisher. We must find instead a cover-address (Deckaddresse)in the U.S.... to which the payment is transferred.”102

Regnery and Scheffer disagreed vehemently with Wilmowsky’s surreptitious approach. “The Ruhr has a right to be heard,” Scheffer declared, and it should not feel the need to proceed under cover, at least with regard to money. Moreover, such financial secretiveness, argued Scheffer, could have serious repercussions. “In an extreme case... it could lead to an investigation by the Senate or the House, which seems to be in vogue today. It would be uncomfortable, to say the least, if it emerged that we represented the project’s origins exactly opposite to the actual facts.”103 This is not to say that Scheffer advocated open discussion of the impending project. “It would not be fatal, but nonetheless damaging,” he wrote, “if the plan was introduced to the public not through your people or the publisher, but through a third party.”

Such a “leak” almost became reality. Scheffer and Lochner were unnerved when they learned that Heinrich Brüning had told Prince Louis Ferdinand about the book during a conversation at Harvard. Nevertheless, “the secret,” Scheffer reassured himself and Lochner, “is in good hands with these men.”104 Despite such concerns about secrecy, Scheffer could not hide his excitement. The book, he argued, would be of high political significance and would help West Germany earn the respect of U.S. policy makers.105 Indeed, he effused, it might turn out to be among the most significant books of the preceding two decades.106

By the spring of 1952 the project had begun to take shape. Lochner revealed his plans to the excited press director for the German Diplomatic Mission in Washington,107 while Lochner’s friend and fellow international journalist Dorothy Thompson briefed a group of enthusiastic U.S. businessmen about the impending trip.108 Back in Germany some of the biggest names in German industry were also preparing for the journalist’s arrival. Heinz Nagel, who had built a large document archive for the Nuremberg defense, was readying his collection for the months of research ahead.109 In February Wolfgang Pohle and Wilmowsky held a meeting at the Düsseldorf Industry Club to inform their colleagues of the latest developments.110

At the meeting, despite general support, they encountered a few lingering doubts. Some people still questioned the necessity of the project, while others took issue with the choice of Lochner as author. In a letter to BDI president Fritz Berg about the meeting, Wilmowsky also revealed a third worry: “that through this investigation, contributions of the German industrialists to the NSDAP could be uncovered.”111

In July 1952, after two years of preparations and several small setbacks, Lochner finally flew to Germany to begin his project on German industry and Nazism.112 Upon his arrival, he met with Krupp’s legal advisers for a brainstorming session. He then immersed himself in the papers of the Industry Office, while archivist Nagel arranged interviews with industrialists around the Ruhr. When he was not reading through musty files at the IHK Essen, Lochner was traveling around the country looking for people with stories to tell. From July 1952 until February 1953 he established contact with hundreds of company leaders and public figures, many of whom he had met and befriended during his years in Berlin. He spoke with chemical executives, textile manufacturers, managers of electrical firms, shipping magnates, banking executives, and the head of the Zeppelin works.113 He met with economists, lawyers, archivists, and company secretaries. August Heinrichsbauer, Hans Ficker,114 and Kurt Hesse told him individually of their failed attempts to write the definitive defense of German industry.115 Hermann and Paul Reusch recounted for Lochner their removal from the GHH board for anti-Nazi insubordination in 1942.116 Ludwig Kastl, the former executive director of the RDI, welcomed Lochner to his farm in Bavaria and told of his and RDI president Gustav Krupp’s disdain for the Nazis. Ferdinand Porsche Jr. gave Lochner documents purportedly demonstrating that Hitler had betrayed his father, the founder of Volkswagen. According to the young Porsche, even after Hitler committed himself to war in 1937, the Führer had assured his father at a personal meeting that his aims for Germany and Volkswagen were purely peaceful.117 Volkswagen became one of the most important military contractors and employers of compulsory labor during World War II.

One of Lochner’s most interesting meetings was with Walter Rohland, the former managing director of the VSt and the former deputy leader of the Iron Industry Group, a compulsory trade organization formed by the Nazis during the war. The controversial and often vilified Rohland explained over several bottles of wine that he had in fact protected industry by cooperating with the Nazis. If he had not joined the NSDAP in 1933, the criminal elements would have ruled the party. If he had not accepted the position of a deputy führer of the Iron Industry Group, he would have jeopardized his future in industry and, worse, “politicians would [have been] installed as leaders of our organization.” As nightfall descended and his discussion with Lochner drew to a close, Rohland concluded with a bitter complaint about the destruction of his family estate by Allied bombs. With that act, “the account with the Jews is settled” (Damit geht die Rechnung mit den Juden auf), Rohland declared as he accompanied a shocked Lochner and his cohort Heinz Nagel to the door. Outside, the two men sadly confirmed to each other that they had not misheard their host. Rohland had, as Lochner later observed, equated genocide with the destruction of his garden.118

As a bizarre aside, when Tycoons and Tyrant, which included direct quotes from Rohland, was finally published, Rohland wrote to Lochner claiming never to have met the journalist. Lochner wrote back to Rohland reminding him of the exact date and time of their interview and the fact that they had drunk a lot of wine. He also reiterated his shock at Rohland’s equation of the murder of Jews with the destruction of the industrialist’s property. Rohland wrote back to Lochner and profusely apologized for having forgotten the interview from three years earlier, and he explained that by his Jewish comment he had only meant that the “victimization” of Germans was part of the price to pay for what happened to the Jews. His own Jewish friends, insisted Rohland, were of the same opinion. “The score is settled,” they purportedly told Rohland with outstretched hands.119

That summer and fall Lochner spoke with old journalistic acquaintances, including Marion Dönhoff, Paul Sethe from the Franfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, and Friedrich Stampfer from the SPD’s Vorwärts. He also traveled to Bonn and Frankfurt to apprise members of the West German government and the U.S. High Commission of the project. While in Bonn, he interviewed Economics Minister Ludwig Erhard and Rüdiger Schmidt of the Economics Ministry. Paul Löbe, former Reichstag president sent to a concentration camp after Hitler came to power, spoke with Lochner about the waning years of the SPD before the party’s suppression in 1933. John McCloy met with him on a number of occasions to talk about this and a different project Lochner was carrying out for the State Department. Finally, Lochner met with some of the most influential politicians in Germany: West Berlin mayor Ernst Reuter, SPD Bundestag member Carlo Schmid, State Secretary Walter Hallstein, Finance Minister Fritz Schäffer, FRG president Theodor Heuss, and Chancellor Konrad Adenauer.

In December 1952, with the bulk of his research behind him, Lochner sat down with Otto Kranzbühler and Krupp director Fritz von Bülow to update his backers on his travels and findings during his six months in Germany. Kranzbühler was particularly curious about what Lochner had learned about the most contested issues regarding industrial complicity: the claim that big business had financed Hitler’s rise and that it had provided Hitler “with a platform for acquiring respectability.”120 Lochner had certainly spent much time wrestling with these themes. Former German chancellor Franz von Papen had sent Lochner copies of exchanges he had recently been carrying out with his predecessor Brüning about the fateful years before Hitler’s ascension.121 At the Düsseldorf Industry Club, Lochner had spoken at length with some of the men who, twenty years earlier, had listened in the same building to Adolf Hitler’s half-baked economic theories and his fulminations against communism. Some told Lochner of the enthusiastic response granted to Hitler after his 1932 speech, while most denied that the industrialists had been impressed at all.122

Despite this impressive research, Kranzbühler discovered to his dismay that Lochner still did not have the story straight regarding the funding of the NSDAP. “Herr Lochner was still not clear as to whether [industry] had financed Hitler before the Machtergreifung,” wrote a surprised Kranzbühler to Wilmowsky. The Krupp attorney was forced to remind the journalist again that “aside from the support of Thyssen and Kirdorf, there is no evidence of significant support from industry circles.” He also referred Lochner to a book by an unnamed Dutch writer arguing that American banks rather than German industry had funded Hitler before 1933. But whoever funded whom, Kranzbühler maintained, one should, in the end, not make too much of the financial issue, since according to Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels’s diary, which Lochner himself had edited and published in English, party coffers were empty at the time of Hitler’s ascent to the chancellorship.123

At this point we must examine why German industry was so interested in the years prior to 1933. Industry was, of course, responding in part to the priorities of its Marxist critics who saw National Socialists as the servants of capital. These critics focused on the last years of Weimar as a tumultuous period when “finance capitalism” naturally paved the way for a fascist victory. A rather different explanation of fascism appeared in the United States, where some elites embraced a Jeffersonian ideal according to which powerful big business interests marked the ruin of the shopkeeper, the entrepreneur, and the farmer. In examining Germany they saw Weimar as the culmination of this process whereby industrial modernization and economic concentration had forced the disgruntled lower middle class into the arms of the Nazis. Even those who did not identify per se with an ideological critique of big business focused on the last years of Weimar as a time when German elites still could freely direct the fate of their country. Politicians and industrialists were faced with a seemingly clear option of supporting the forces of authoritarian and rightist dictatorship or defending a shaky but nonetheless democratic order. They made the wrong choice, and National Socialism was the catastrophic result.

Not only critics of big business but industrialists themselves devoted the bulk of their attention to the Weimar years. This can be explained in part by postwar German elites' fatalistic view of the Nazi years. According to most postwar corporate apologias, after 1933 there were few possibilities of resisting Hitler. The Third Reich acquired a momentum of its own, fueled by the intoxicated masses and drawing in everyone, including its “apolitical” economic elites. After Hitler came to power, so this interpretation continued, events spiraled to their natural end, and the moments of choice for industry became fewer and farther between. In the view of postwar industry, the true questions of guilt or innocence did indeed lie in the final years of the Weimar Republic, a time when industry felt it could demonstrate successfully that it had not collectively funded or embraced Hitler.

In privileging industry’s pre-1933 attitudes and behavior, industry’s critics paradoxically gave businessmen the opportunity to downplay or justify their concessions to the Nazi regime after 1933. With the fear of Soviet communism as the backdrop, after the war industrialists could argue to the public with greater ease that the forces of the total state took away all free will. Industrial cooperation with the state was simply the inevitable result of living under a totalitarian regime. Ironically, however, by insisting that they had had little Handlungsspielraum (room to maneuver) under Hitler, industrialists were actually acknowledging that their behavior after 1933 was damning on a collective level. By keeping the emphasis of the discussion on events before 1933, industrialists took refuge in the memories of a less threatening time—before they had joined the party, before they dismissed their Jewish employees, and before Kristallnacht, war, and mass murder—in short, before their own, albeit “undesired” and “forced” complicity.

Importantly, this emphasis on the Weimar years did not by any means preclude a discussion of behavior after the Nazi takeover; it simply elevated Weimar to the first and most important order of business. With respect to the years after 1933, industrialists offered Lochner what were by then well-honed images of impotence, resistance, and victimhood. If the industrialists had no choice when it came to matters of racial policy and rearmament, they did manage, in their words, to commit acts of everyday defiance—from the avoidance of the expression “Heil Hitler” to criticizing the Nazis at board meetings, to resisting divorcing a Jewish wife, to providing extra rations or better-quality food to forced laborers, to refusing to carry out Hitler’s self-sabotage orders in the spring of 1945. Lochner came away from his research with a number of such examples of everyday Resistenz.124

These examples of defiance, which had obviously been ineffectual challenges to the regime, are not necessarily postwar inventions or embellishments. The reality of life in Nazi Germany was such that cooperation, indifference, or a general sense of impotence could be combined with local or selective acts of disobedience. By claiming to have spoken out against a particular policy or to have selectively resisted some aspect of the regime, one was not necessarily claiming to be a hero. But the contradictions and tensions in this notion of opposition do become significant when we consider how often industrialists granted equal status to both forms of behavior—impotence and resistance. Industrialists saw themselves both as the object of forced measures and as courageous challengers of the Nazi government.

Despite claims otherwise, industrialists behaved politically and opportunistically during the Third Reich. As men accustomed to wielding tremendous social and economic power, they joined the Nazi Party to avoid being shut out of political developments. Especially in 1940, as Germany racked up military successes, industrialists made peace with the regime in order, among other reasons, to have some voice in postvictory decision making. They were not about to sit out the “thousand-year Reich.” After defeat, however, industrialists were loath to concede their pragmatism or to portray themselves in such amoral (or immoral) terms. They tried to recast their self-interest as ethical behavior, usually with unconvincing results. Thus we encounter somebody like Walter Rohland paradoxically insisting that his decision to cooperate with the Nazis was at once a freely chosen attempt to avert the worst aspects of the regime and a response to a dictatorial fiat.