3

The Power of Appreciation

Like training racehorses, sailing a motor-yacht in the ‘Med’ and remodelling an extravagant home, collecting art is uniformly regarded by historians as one of the expressions of great wealth. The equation is easy to make. From the mid-nine-teenth century, exhibitions of contemporary art became popular with the general public and the connection between the ownership of important exhibits and public approval was frequently inferred. Even in those days, there was a whiff of infallible latter-day logic about the rationale – namely that the best way for a successful businessman to become more successful is to go out and buy something apparently pointless. So a sugar manufacturer of the 1880s has to commission a large lugubrious picture of a dying child in a dingy cottage and present it to the nation (Fig. 19).1 As a business strategy, this seems baffling at first. Yet it is one of the keys to the study of art collecting. Henry Tate’s benefaction had its moment. Within a few years it might be regarded as absurd and embarrassing. In 1903 Charles Holmes wrote about benefactions of this kind – ‘if you have … bought sentimental pictures … present them to your local gallery as quickly as you can. You will then have the reputation of an art patron and public benefactor. If you send them to Christie’s it will be discovered that you are a fool.’2 A study of the fashions and fluctuations determining the impact of certain types of wealth upon markets in new and recently new pictures is essential to the understanding of the art world at the turn of the century.

How did the age talk to itself about the magnetism which drew audiences to works of art? There were agreements about their talisman quality, their ability to fix visually a person or place, a set of circumstances, or a narrative. There were shifting beliefs about their power to release memories and engage the imagination, and, eventually, around 1910, attempts through formal analysis to suggest that their primary satisfactions lay in things other than the matter which was being represented. These underscored a popular consensus on the artist’s ability with paint and canvas to transform something of life into a material object, a pic-ture in a frame, hanging on a wall. Then, there was a less verbalized but no less powerful consensus on the spectator’s confrontation with this object, the by-product of which was to translate its picturing back into reality – a superior reality in the life of the mind.

However, a new and important purpose for art collecting which emerged in the late nineteenth century was that of investment. Fine paintings were the ultimate objets de luxe, and as such, unlike other art forms, they had a high commodity value. Against the popular demand for the democratization of the experience of art through the establishment of public galleries, the support for private ownership was increasingly vocal.3 Ruskin, in his lectures on The Political Economy of Art, had set out roles for both public and private patronage which broadly confined the acquisition of past art to public galleries, while contemporary art should be bought by individuals. Ruskin drew the parallel between the public and private consumption of art and literature, and declared the statutory obligation of municipalities to ‘bring great art in some degree within the reach of the multitude’.4 Holmes, in his primer on collecting, was more in favour of private possession. The best training for the eye,’ he wrote, ‘is habit, and habit cannot be wholly acquired in museums or galleries. The stimulus of possession makes one examine more closely, consider more lengthily and compare more carefully.’5 This was the period of sophisticated theorization of ‘possession’, ‘pleasure’ and ‘profit’ in Mauclair, Veblen and others.6 Unlike other luxury goods, works of art were increasingly expected to produce a profit when sold, and prospective collectors required assurance on this point. How did these expectations determine appreciation and acquisition? All art consumption starts with the apparently simple act of seeing. Immediately, however, the viewer becomes involved in a practice which is socially and historically constructed and is not value-free. It draws upon mentalities and coexistent communities of images, available to social and cultural elites, which have to be reconstructed with forensic zeal by the historian of visual culture – in so far as they ever can be.7 Having examined attitudes to the perception of market sectors in the art of the past, it is now necessary to look at contemporary and near-contemporary production. What is the difference? Sartre and other writers have sensitized us to the fact that the work of art, from whatever era, brings the past into the present.8 At the point at which it is viewed, history and context fall silent.9 In themselves, emerging and declining image communities give the sense of the shifting meaning of visual literacy at the turn of thecentury. The linguistic model is appropriate. Schools and movements in art history, even in the standard modernist accounts, become speech patterns or different sets of linguistic conventions, of which there is a heightened consciousness at a time when unanimity on style has broken down. Old words form new sentences, usage alters definition.

Thus, by the 1850s there were picture shops. Dealers bought and speculated, and hopefully turned a profit. The availability of pictures was advertised. Exhibitions were staged, written up and reviewed. We are in what Reitlinger described as ‘the golden age of the living painter’. The exchange systems functioned broadly as they do today. Auctions, after the Marlborough sale of 1884, became more protninent.10 The market in contemporary art was challenged by the secondary markets in older art at the turn of the century. Although these fluctuated with fashion and with conditions of supply and demand, the trade in older art claimed precedence around 1900. A fictional discussion in the columns of The Studio, in 1904, makes the point. A dealer boasts of his success in selling an old master painting for £10000, a price which dazzles even him and which would be impossible for a contemporary work. ‘Art collecting now-a-days,’ a fictional critic replies, ‘is guided neither by taste or reason, but merely by an irrational spirit of competition. It is one of the forms of excitement cultivated by millionaires who have more money than they can spend in any sensible fashion.’ The Academy is castigated for its old master winter exhibitions, the dealer’s ‘valuable ally’, while the artist sits in a studio ‘crowded up with unsold works’, thinking that a picture by ‘some ancient bungler’ is worth more than good things of the present.11

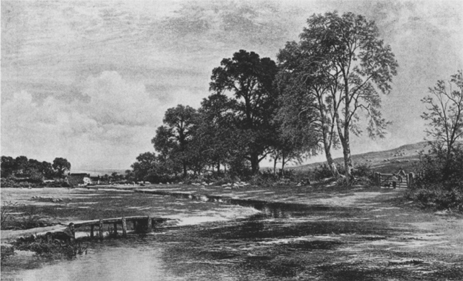

As Reitlinger pointed out nearly 40 years ago, between 1880 and 1910 the character of the market changed in fundamental ways.12 The liquid capital which chased contemporary art from the 1860s onwards began to diversify into secondary markets by the end of the 1890s. Art historians have standard ways of accounting for this, by citing the emergence of the avant-garde and the gradual erosion of the power of establishment institutions – the Royal Academy and the old exhibiting societies. And while these things were undoubtedly going on, our histories often fail to take account of changes in taste, in the social attitudes and ideas which clothe the collector of art at the point of purchase.13 Thus, those who bought Pre-Raphaelites in the 1860s might be expected to take an intelligent interest in philanthropy, in working-men’s colleges and the condition of the poor,and maintain a low profile in the disposal of wealth, while the collector of contemporary art in 1890, who was much more ostentatious, was looking for the approval of peers and the public validation of his or her enterprise. This was the sort of individual who collected only to outstrip everyone else. Such a determined type, in a George Moore narrative, who has ‘money-grubbed for five-and-twenty years in the City’, after a good dinner, clouded by drink and tobacco, finds himself locked in conversation with his host, ‘a brewer or distiller’, on the subject of art, about which he knows nothing. They are gazing at a Benjamin Williams Leader, a Leader which the brewer has just bought for £1500, and the boozy money-grubber instantly determines that he too should have one – ‘Mr Leader put RA after his name – he charges fifteen hundred. Besides, the village on the river bank with a sunset behind is obviously a beautiful thing’ (Fig. 20).14

20 Benjamin Williams Leader, By Mead and Stream, 1893

Moore’s hero typifies numerous copycat collectors of the 1870s, 1880s and 1890s. The art they bought was produced by respected names, usually academicians who produced ‘pictures of the year’ as much for reproduction as for sale. Alphonse Legros, who advised on many of the pictures in the Ionides collection (now in the Victoria and Albert Museum), at the time when ‘pictures of the year’ were sold with copyright for vast sums, recalled his patron saying, ‘“and now, I beg you, buy some costly pictures”. The collector wanted to make a loud splash of money that newspapers would chronicle.’ Legros, interested only in quality,could not understand this impulse. ‘“What could one do with such a person?”,’ he commented ruefully.15 Then, as now, some collectors bought as a way of calling attention to themselves and an expensive Leader which made a splash, rather than a Degas which brought risk and notoriety, was a way of achieving this. Leader’s quality was assured by its recognized commodity value. Aesthetic acumen took second place to the acknowledgement of the purchaser’s ability to pay. It matters little that Leader’s work looked like a tea tray, everyone needed to have an example, and it was upon this which the turnover of the Academy cartel depended. It was also not surprising that this vulgarian taste was visited upon the newly forming municipal collections since their purchasing committees were composed of the local brewers and money-grubbers. What better way to underwrite your investment than to ensure that the city art gallery had also bought a big important Leader from this year’s Royal Academy?

This was going on around Moore as he wrote. He recognized the pace of change, and that the value of the academician’s stock was not set to rise for ever. Indeed, he and other progressive critics constituted a serious threat to the livelihood of popular academicians. The new British art outside the Academy was more cosmopolitan, and thus more directly related to what was going on in Europe than to perpetuating native traditions. Northern industrialist collectors favoured this kind of painting. Like them it came, apparently, from nowhere, trailed no traditions and embodied the hard-bitten, self-made way in which they viewed the world. In their collections a large recent Salon painting might hang beside the work of young British painters who espoused similar ideals. Thus Isaac Smith JP, Mayor of Bradford, owned plein-air naturalist pictures like Edouard-Joseph Dantan’s huge Les Guideaux à Villerville-sur-Mer (Calvados) (The Stake-Nets at Villerville) (Fig. 21), purchased through the London trade after its initial showing at the Salon of 1886, and hung it next to works like Leaving Home, by the young French-trained British painter, Henry Herbert La Thangue. The scale and quality of the works collected often meant that annexes were built to the side of the villa specifically to house the picture collection, and it is in these private surroundings that we find one of La Thangue’s other Bradford patrons in his picture, The Connoisseur (Fig. 22).16 Here the isolated contemplation of the patriarch, Abraham Mitchell, on the right, is contrasted with his family group at the tea-table on the left, in the gallery of his palatial home Bowling Park, at Rooley Lane, Bradford. Mitchell holds a large magnifying glass and is lost in thought. Adynasty of textile manufacturers is led out of the world of trade and into the ambience of art by this dreamer, for whom to be viewed in the study of works of art evidently was more important than to be seen scanning commercial reports, accumulated surpluses, ledgers and receipts.

Up to this point connoisseurs in the nineteenth century had been costume-piece characters. As the activity validated itself it was assumed that there must have been occasions in the past when men and women abstracted themselves from the world of affairs and studied works of art. Men were frequently portrayed as connoisseurs in the work of Reynolds, Batoni and Zoffany. Successful genre painters of the mid-nineteenth century like Meissonier and Stevens clearly concluded that there must have been rendezvous in studios in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in which the artist would unveil his work to the delight of onlookers and for the purpose of making a sale. There was even the assumption that the conditions of modern commerce must have existed in ancient times in Alma-Tadema’s The Picture Gallery (Fig. 16) which, as Elizabeth Prettejohn has reminded us in an exemplary catalogue entry, contains all of the leading contemporary dealers who were active on the painter’s behalf.17 These set the precedents for La Thangue’s Connoisseur.18

But Mitchell is a man of today. How did he get tangled up in all of this? What did he have to do to prove to others that he was not simply a mill owner? The wisdom about forming a collection extended to how you might organize your immediate surroundings. P. G. Hamerton, editor of the Portfolio, recommended collectors to avoid miscellaneous purchases. Everything in a collection should cohere; there should be some ‘great leading purpose’ which will give unity to the whole. The collector should be sensitive to differences of scale and subject matter within a single room. In a domestic setting pictures should be ‘intellectually in harmony with the uses of the room’.19 Mitchell, the true addict, had solved that latter problem by getting out of the house and creating his own nirvana. La Thangue’s group portrait asserts his role as seer – or is it simply that Mitchell has arrived at that point in life when a man is bewildered and realizes that he does not really know what he has done or why he is there?20 Nevertheless in grim industrial Bradford he had created a shrine and, on an artist’s easel, set up his own household gods.

Mitchell’s reverie is comparable to that of many other less complex portraits of contemporary collectors, like George Henry’s portrait of the railway magnate,James Swats Forbes, in 1903 (Fig. 23). Forbes at various times owned work by contemporary painters like Clausen and Bastien-Lepage, artists whose cause may well have been advocated by his nephew, Stanhope Forbes.21 In this portrait, the concentration on the sitter is increased by the fact that circumstantial detail has been reduced simply to the man and his picture. Once again, the viewer is not permitted to see the picture which absorbs the sitter’s attention. La Thangue’s and Henry’s connoisseurs are caught in what must have been a rare moment of respite. Their acquisitive instinct was such that writers of the period often marvelled at their capacity to absorb everything they bought. It fully justified the creation of special circumstances for storage and display.

A private gallery like Mitchell’s, however, was the ultimate absurdity to George Moore. He wrote that it was, ‘a monstrous and ridiculous anomaly which no one would build but a retired cheesemonger … A private picture gallery is a room fifty feet long with an oak floor and some chairs and an ottoman – a something which jars with the harmony of the rest of the house, reminding you disagreeably of an hotel sitting-room.’22 Moore was an unabashed elitist for whom social superiority was the necessary precondition of connoisseurship. He acquired his attitudes from France. During the previous decade, in addition to being one of Manet’s sitters he had been one of the first writers to absorb the work of the Goncourts and J.-K. Huysmans.23 Wealth, indulgence and copiously cultivated ‘aristocratic’ taste were incompatible with the suburb. Great masterpieces were unsuited to the villa.

The contemporary painter’s obligation should not therefore be to provide exhibition pieces in gilt frames which demanded vulgar populist viewing conditions, but what Sicken later referred to as small pictures for small patrons. There was a legitimate market for what formerly had been known as cabinet pictures and Moore may reluctantly have been in general agreement with Hamerton on matters of hanging, with regard to eyeline and to the convenient observation of detail on the picture surface. Three or four good paintings, well placed in the domestic setting, ought to be enough to sustain the weary cheesemonger. There was nevertheless throughout his writings an implicit approval of the mind whose communion with art was a solitary pastime. Taste in pictures was something which developed slowly and works of art might only reveal their value gradually, like the slow release of a narcotic into the blood stream. The Wildean ‘aesthete’ buffoons by George du Maurier cast the experience into a series of histrionic poses to which the cheesemonger could, and should, never aspire.

21 Edouard-Joseph Dantan, Les Guideaux à Villerville-sur-Mer (Calvados), 1885

23 George Henry, James Staats Forbes, 1903

22 Henry Herbert La Thangue, The Connoisseur, 1888

By 1900, ‘cheesemonger’ collectors had matured in various ways. Some, like Tate or Thomas Holloway, used their collections of contemporary art as leverage or added value in founding galleries or educational establishments. Others, like the Bradford collectors, Maddocks, Smith and Mitchell, stopped collecting and eventually brought their collections to market.24 Yet others, like William Hesketh Lever, abandoned the contemporary field for eighteenth-century portraits and selected old masters.25 Of modern artists, only Millet, Watts and Whistler were regarded as suitable companions for a classic millionaire old master collection.26 For his portrait, the millionaire should only go to Sargent. The rules of engagement for a masterpiece collection were very strict. By contrast, those who were merely rich had a broader remit and could experiment, although, according to Holmes, some currently fashionable areas, such as portraits of pretty women, should be avoided.27 A ‘rich man might fill a small room with works of the Pre-Raphaelites’, because these were becoming rare and were not yet as expensive as a Gainsborough or Reynolds.28 The poorer the collector, the more cautious and disciplined he or she would have to be – applying knowledge and skill in acquiring works which will be of greater value in the future, and in the setting of a themed and co-ordinated collection. Holmes was vague on issues of class. His collectors were either ‘millionaires’, ‘rich’ or ‘poor’. It was only in the columns of The Burlington Magazine that the passing of the ‘middle class’ collector was bemoaned. Here again definitions were vague. It was more important to note that these individuals, the ‘self-made men’, often ‘of obscure origin’, had gone. Sparked off not by Holmes’s book, but by an article in The Academy, its editor accounted for the lack of confidence in contemporary art. Prices of original pictures, relative to other luxury goods, pleasure yachts and motor cars, were too high. The collector of modest means contented himself with photogravures, while the very wealthy treated picture-buying as they did the acquisition of preference stock. In the Edwardian years there was overproduction and an inflated market. It was up to artists to come together, restore confidence by rationalizing their confusing array of groups and societies.29

In the new market conditions at the turn of the century, Holmes was more explicit than the Burlington editor in delivering caveats on contemporary art. The would-be purchaser, like Moore’s cheesemonger, will be ‘dazzled by societies, entertainments and titles’ into overpaying for what is at best mediocre. Academy dinners and puffed-up professional honours were no guarantee against the picturebeing a disastrous loss. Dealers had tried to shore up the market, but the naïve burghers of Birmingham and Manchester were no longer naïve. With his eye upon Ledbury Road and St John’s Wood, he struck out at academicians who ‘must live expensively and charge corresponding prices’. Greed and extravagance had ruined the contemporary market, making it impossible for dealers to recommend such work as an investment.30 Although at pains to point out that he is not writing exclusively about contemporary art, Holmes goes on to support the work of painters who were comparatively cheap but, in his view, of high quality, and, given his background, these come from the Slade and New English Art Club camps.31 The Royal Academy was only worth considering for Clausen, La Thangue and Edward Stott and the writer was nervous about the future of the Glasgow School, which, like the Newlyn School, appeared to have disintegrated. The international context for this modern British work was Segantini, Meunier, Cazin and Thaulow, who were popular with British collectors.32

Those who could afford to buy art on a grand scale, usually in the latter half of their lives, were by no means effete. The builders of railways, the owners of mines and cotton mills, the makers of machine guns, brutalized by trade and industry came to art, we are repeatedly told, in an effort to rediscover innate sensitivities. At first they disposed their wealth indiscriminately, acquiring for the sake of acquisition. Forbes’s collection was so vast that it was serialized in The Studio over three issues, and his family, at the time of his death, feared that it would flood the market if released into the saleroom all at once.33 The sheer scale of it boggled the German critic, Julius Meier-Graefe, who visited the Forbes collection just before its dispersal. ‘It consisted’, he wrote,

of I forget how many thousand pictures. To house them, the owner rented the upper storey of one of the largest London railway stations, vast storehouses, but all too circumscribed to allow the hanging of pictures. They stood in huge stacks against walls, one behind the other: the Israels, Mauves and Marises were to be counted by hundreds, the French masters of 1830 by dozens; there were exquisite examples of Millet, Corot, Daubigny, Courbet, etc., and Whistler. Although these stacks of pictures were held up by muscular servants, the enjoyment of these treasures was a tremendously exhausting physical process. One walked between pictures; one felt capable of walking calmly over them! After five minutes in the musty atmosphere, goaded by the idiotic impulse to see as much as possible, and the irritating consciousness that it was impossible to grasp anything, every better instinct was stifled by an indifference that quenched all power of appreciation.34

24 Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Paysage: soleil couchant, 1875

This disquiet contrasts with George Henry’s portrait of the dreaming connoisseur. It raises questions about the very nature of Forbes’s enterprise. Was he an unworldly aesthete or a speculator with a strong fiduciary interest in his stock? Meier-Graefe was convinced it was the latter case. In his terms, the modern conditions of the art market were that ‘sales are effected as at the Bourse, and speculation plays an important part in the operations. The goods are scarcely seen, even at the sale.’ Forbes’s collection was ‘by no means unique’.35 However, although he occasionally culled his holdings during his lifetime, he was a ‘serial hoarder’, rather than someone who trades up through a particular market sector to singular, rare and unique examples.36 And Henry’s picture is not a lie. It confirms the evidence of William Orpen and T. Martin Wood who recorded that Forbes ‘was wont to mount to a big room and have one picture after another wheeled before him for inspection’.37 His particular specialism was Corot and he possessed over 100 works by the painter. He is reputed to have visited Corot on his deathbed at the beginning of 1875 and wrested his last painting from him, Paysage: soleil couchant (Fig. 24), a tiny canvas, similar in size to the framed picture resting on the easel in Henry’s portrait. It is entirely possible that the reverie which has overtaken the collector, himself near death, is the result of gazing at a picture such as this. When he studies his Corots, Staats Forbes is not looking at them so much as looking through them. His gaze is clouded by memory and desire. The old year dies, the new year dawns in a rêve de bonheur. It is the sylvan grove: presently the nymphs come and perform their dance.

Such possessions displace the viewer and arrest the relentless continuum of ‘getting and spending’. Repeated visits to the storeroom, to the same pictures, like playing the same music on a phonograph, take the collector out of time. The sum of his or her possessions, one may claim, is intimately connected to the individual, the personality, and is not simply a trophy or by-product of wealth. As Baudrillard succinctly put it, ‘it is invariably oneself that one collects’. The picture is sewn into experience. After a first encounter, the memory fashions a facsimile of it, an image which will be reworked on subsequent encounters, until it is completely remade in the workshop of the mind. That pictures should come to mean so much, be amassed and consumed in this way, by a railway manager, begins to seem less bizarre. Within a few years of his death in 1904, it became known that there were a number of collections like Forbes’s in Britain – secretly amassed, locked away and now released, with a fanfare of scholarship in the art press. Scholarship is a refined form of publicity. Whilst they varied in quality, the British Barbizon and Hague School collections were different in character from earlier ‘aesthetic’ and ‘pictures of the year’ collections. They contained many small pictures by groups of artists whose work expressed a collective sensibility operating in the low content genre of landscape, emphasizing the painter’s touch. Paradoxically, although these were cabinet-sized works, ideally suited to the domestic interior, they were acquired in large numbers by hoarders who, like Forbes, refused to use them as mere furnishing pictures.38

George Moore was of the view that this kind of painting was suited to suburban sensibilities. ‘Civilization,’ he wrote,

is destroying palaces and building villas; civilization is stealing away from public life and fortifying itself in the family circle; civilization is distributing a modicum of comfort and education and creating a large suburban class living in villas. These people demand art – not historical art in heavy gold frames, but pleasant agreeable art that will fit their rooms and match their furniture … This is the art we need, and this is precisely the art to theproduction of which few have turned their thoughts and taste – an art which is at once an art of handicraft, a hybrid between the picture and the biblot.39

However, the nature of art production was changing in order to accommodate the new need for pictures which did not require advance preparation, which were more about the expression of the individual, or the response to the natural world, than addressing grand ideas. It is unlikely that young painters perched on camp stools, under white sketching umbrellas, painting small landscapes saw it like this, but they would eventually tap a lucrative seam, fulfilling the request for ‘clever’ sketches. The authors of these works were relating to a market; they were only in part directed by dealers’ perceptions of public taste.40 The sense of engagement with an individual maker in the work of the Barbizon painters was an important way-stage in the development of this taste. Making artificial Academy machines was increasingly at odds with the idea of the artist as one who was in continuous dialogue with materials and with quotidian experience. Dealers’ exhibitions of the work of regular Academy exhibitors around 1900 attempted to redress this imbalance.

The lingering gaze of the solitary owner of art haunts the discussion of aesthetic matters at the turn of the century. Even though the leading British art critics were signed up to Pater’s ‘gem-like flame’ description of the experience there was disquiet. Moore had described it thus: ‘a great picture demands the soul, the entire soul, and in return it gives absolute annihilation of past and future, creating a momentary but ecstatic present’.41 If not ecstasy, La Thangue and Henry were trying to portray this sense of suspended animation, of temporary detachment from the world of ordinary affairs, which characterized the experience of art.42 The question of whether this experience was communal and communicable, or individual and private, remained a live issue encircling the collector’s reverie. Staats Forbes is lost in contemplation of the work in front of him, checking it against his memory, responding to it in a different light on a different day, dreaming over it, looking through it to the life it represents, seeing an artificial world, set apart from that of his everyday experience, and resting there for a short time – but recognizing it as constant, everlasting, made by an artist. All of this which he brought to it reaffirmed the mystic power of the material object.43 If he could not be shown subservient to religion, the homme d’affairs was not devoid of spirituality; he felt – or could afford to feel – the drawing power of art.

Why did men like Forbes return repeatedly to the same objects to check that they remained precisely as they were remembered? What had they released in his imagination? What compelling sensations demanded that he come back? Proust believed that the spirits of the past inhabited inanimate objects from which they were occasionally freed. Art alone provided the unique ‘talisman’, because it had the power to fix a person or a place in time. The artist unwittingly partook in a shared memory. His or her image became the spectator’s past. Fascinated by the artist’s power to translate life into a work of art and then for the collector to rework the painted scene into the life of the mind, artists and writers on art were forever grasping at shadows. The genre, paintings representing the aesthetic moment, re-emerged in portraits like Bastien-Lepage’s Sarah Bernhardt (Fig. 25) which showed familiar people having superior thoughts, in pictures which portrayed the beauty of contemplation. A girl picks up an object – a small sculpture or a piece of Staffordshire – she gazes upon it; she is lost in thought. Edward Arthur Walton, Robert Brough, James Jebusa Shannon and Henry specialized in this saleable commodity. Such pictures told the viewer what he or she might ideally look like when looking. They visualized the aesthetic experience, and as such are not to be taken at face value. They transpose the beauty of the object into that of the woman. They objectify the woman and carry the covert message that in the presence of art, the viewer might, with heightened consciousness of self, also become art. Eighteenth-century connoisseurs who had looked for a long time at Apollo Belvedere instinctively adopt its magniloquent stance. Equally, these women painted by Walton, Brough, Shannon and Henry naturally strike poses. The experience of art is translated into social deportment. It is an invitation, principally to male viewers, to contemplate a woman’s beauty. The object of contemplation in the picture has been sacrificed to the painted viewer, which then, in turn, becomes the new object of contemplation. It becomes a request to dance, to shed tears, to take intimate pleasures, to reconsecrate.

25 Jules Bastien-Lepage, Sarah Bernhardt, 1879

26 James McNeill Whistler, Symphony in White, no. 2, The Little White Girl, 1864

The modern origin of this strand of painting, particularly in the 1890s, lay in Rossetti and in Whistler’s Symphony in White, no. 2, The Little White Girl (Fig. 26), a work which was brought back into currency.44 Although ostensibly about narcissism, the girl in Whistler’s picture looks longingly in the direction of an oriental pot.45 Hers is the first of many languid arms which reach out for the aesthetic object. Brough’s and Henry’s women might be more flighty or more sophisticated, but their intention, touching beauty, for which the object is a talisman, is the same.46 Berenson subscribed to this view of the aesthetic experience, although he did not give voice to it until much later in his career. ‘The aesthetic moment,’ he wrote,

is that flitting instant … when the spectator is at one with the work of art he is looking at … He ceases to be his ordinary self and the picture or building, statue, landscape, or aesthetic actuality is no longer outside himself. The two become one entity; time and space are abolished and the spectator is possessed by one awareness. When he recovers workaday consciousness it is as if he had been initiated into illuminating, exalting, formative mysteries. In short, the aesthetic moment is a moment of mystic vision.47

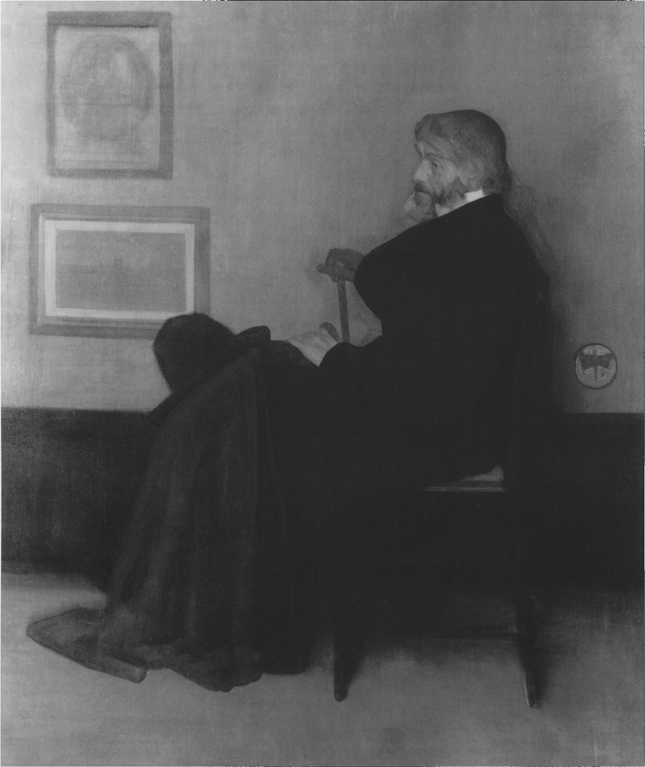

Putting Henry’s connoisseur back into the context of real acquisitions which have to be fought for in the competitive arena of the saleroom adds a new dimension and takes this out-of-time experience back into a crudely literal world. It brings with it the sense of the spiritual importance of the material object – something which although exchanged within a system of trade continued to be regarded as a thing beyond value. For those who paid for them, works of art had a very precise value. They might be acquired through complex negotiation or in the teeth of competition, but they were reduced to a sum of money in the end. There is a history of private haggling which remains largely inaccessible. The fragmentary evidence tends to confirm obvious assumptions about individuals looking for the best price. In the action of committees, the link between price and value was forged embarrassingly in public. Those charged with disposing of sums from the municipal purse had a special duty in this regard. The idea that something so bureaucratic as a corporation should be able to move quickly to secure an important purchase against competition suggests the presence of an aesthetic consensus backed by a formidable corporate will. Ideas such as this were, as we have seen, increasingly under scrutiny. Were the industrial cities of the north of England and Scotland vying with one another like the city states of Renaissance Italy? Was there a municipal aesthetic, an occasion when the burghers of Manchester or Glasgow came together in front of a picture, were moved by it and agreed to buy it? If such emotions were felt they were not openly admitted. It is clear in the celebrated case of the purchase of Whistler’s Arrangement in Grey and Black no. 2, Thomas Carlyle (Fig. 27) by the baillies of Glasgow, that aesthetic matters were reduced to a few practical questions which produced surprising answers. ‘Modern pictures don’t stand so well as old masters? The colours, they say, fade sooner?’ … ‘No it is not true – modern pictures do not fade and therein lies their complete damnation’ … ‘The tones of this portrait are rather dull, are they not? Not very brilliant, are they?’ … ‘Not brilliant! No, why should they be? Are you brilliant? No. Am I brilliant? Not at all.’48 For the rest it was a matter of haggling over the price and hoping for a reduction. The worth of the picture in aesthetic terms had been established long before this stage as a result of the substantial lobbying by the Glasgow School painters.

This is, nevertheless, one of those rare recorded occasions when a group of individuals came together and purchased a picture which was not momentarily fashionable, but was regarded as important – if only primarily for its subject. There were many more examples of dithering and indecision – a fatal combination of what, in 1893, George Moore described as ‘vexatious discussion and lost chances’.49 For Moore there was something fundamentally flawed about the very concept of the municipal gallery. It lay in the nature of the individuals and their responsibilities. Uncertain of their footing in matters of art, aldermen looked for exemplars to the Chantrey Bequest, a purchase fund for contemporary art for the national collection, administered by the Council of the Royal Academy. ‘The Manchester and Liverpool collections are weak reflections of the Chantrey Fund collection’, Moore declared.50 They were, in effect, the public manifestation of ‘pictures of the year’ collecting. They sought to represent what the public was thought to want; they confused aesthetic education with moral improvement, jingoism and other trivial emotions. They were deflected by momentary fashion.51 Their committee structure meant that agreement was seldom possible, and when it was obtained, they could not act quickly. A policy or judgement which guided one acquisition might be overturned by the time the next was being considered, and thus the collections became no more than a miscellany of the currently fashionable. ‘That it should ever come to be believed that twenty aldermen, whose lives are mainly spent in considering bank-rates, bimetallism, and sewage, could collect pictures of permanent value is on the face of it as wild a folly as ever tried the strength of the strait waistcoats of Hanwell or Bedlam,’ Moore concluded.52 Ten years later, Holmes came to the same conclusions.53 In 1905, however, The Burlington Magazine began to observe a sea change.54

27 James McNeil Whistler, Arrangement in Grey and Black no. 2, Thomas Carlyle, 1874

Moore’s observation that these provincial collections aped the Chantrey Bequest was apocryphal. By 1904 there was sufficient volume of complaint orchestrated by D. S. MacColl, about the acquisition of works under its aegis, for a House of Lords Select Committee to be established.55 Long after ‘pictures of the year’ with reproduction rights had ceased to be popular with millionaire collectors, the Bequest was annually spent upon expensive, prosaic works by academicians, rather than inexpensive works by the avant-garde. The enterprise cast doubt upon the public trust accorded to a group of experts. In response the Academy became more deeply entrenched. After sitting upon the Select Committee’s recommendations for a year, it rejected them, while implementing them in practice without fanfare.56 Nevertheless the tension between wishing to be ‘representative’ and risking the charge of producing an incoherent miscellany was ever present. There were even those who contended that there was a convoluted virtue in spending large sums of money out in the open market upon known and reliable commodities, rather than operating through agents to acquire objects, the value of which had not been attested.

Moore, MacColl and Holmes took their cue from Whistler in arguing against an institutionalized and ‘democratic’ aesthetic. For Whistler, good art was the byproduct of public indifference. There should be no expectation that the public, through state or municipal agencies, would have anything significant to say.57 That Whistler saw the need to deliver this message in 1885 is an indication that the public appreciation of works of art was a matter of concern. Art was considered as an agency for social good; it should be morally and publicly accountable.58 Ruskin, as we have seen, had set the brief for municipal collecting. These ideas were articulated with renewed emphasis by Leo Tolstoy in 1898, when he declared that ‘for a work to be esteemed to be good and to be approved of and diffused it will have to satisfy the demands, not of a few people living in identical and often unnatural conditions, but it will have to satisfy the demands of all those great masses of people who are situated in the natural conditions of laborious life’.59 The new critics, including Holmes and Fry, took the view that the rendering down of contemporary art, from savant to populaire, involved too many compromises.

Against this resolute pursuit of mediocrity was ranged the singular purpose of the committed collector. Although Holmes qualified his name-dropping, there was a group of new collectors in line with his artist choices. These were drawn from the professional classes – publishers, lawyers and academics – and their tastes were served by dealers like David Croal Thomson and Lockett Thomson, and celebrated in the columns of The Studio. Thomson and Hugh Lane were responsible for recycling some of Forbes’s pictures into these new collections, the byword of which was ‘eclectic’, a term taken to mean the liberal mixing of the best of contemporary art – principally drawn from Holmes’s list – with selected examples of the Barbizon and other nineteenth-century schools. The collector – someone like Judge Evans, whose eye for quality overruled the apparent inconsistency of having works by Richard Wilson, Spencer Stanhope, Adolphe Monticelli and William Orpen hung together – was making up a new story.60 With American specialist ‘masterpiece’ collections beginning to be built simultaneously, there was room for serious debate about the ability of an individual to appreciate quality across a range of diverse fields. Nevertheless critics like Moore and MacColl were driven to maintain the primacy of the connoisseur, whether he or she functioned in a private capacity or as the director of a public gallery. Collections could not be formed by committee fiat. They should be formed by individuals who might then present them to public museums for the appreciation of all. Julius Meier-Graefe proposed this philanthropic role for the collector, affirming, controversially, the superior conditions of the modern museum where, he contended, old masters could be seen to greater advantage than in the places for which they were painted. The aesthetic experience must be democratized in an institutional context and the early attempts to do this in the 1880s, with large narrative or naturalistic pictures, had been naive. Taking an opposing view to that of George Moore, he asserted that private houses were not suited to the display of some works of art – ‘a picture that disturbs our sense of well-being is clearly out of place in a house’. The idea of the amateur was acutely problematic in an age which was now experiencing the disjuncture of ‘work’, increasingly defined as cerebral, and involving the exercise of will rather than physical energy, as opposed to ‘home’, defined as a place of comfort and recuperation.61

Read in the English context, these perceptions contained an implicit underscoring of English eighteenth-century aristocratic culture. In the great house, as distinct from the suburban villa, or even the modern municipal museum, the ambience of art was somehow a natural extension of civilized life. Like the original dilettante more recent collectors, according to Roger Fry, wanted ‘to buy something which is incommensurate with money. Both want art to be a background to their radiant self consciousness.’ However, ‘the aristocrat by his taste, by his feeling for the credentials of beauty, did manage to get on some kind of terms with the artist. Hence the art of the eighteenth century, an art that is prone before the distinguished patron, subtly and deliciously flattering and yet always fine. In contrast to that the art of the nineteenth century is coarse, turbulent, clumsy.’62 Taste in pictures, in the eighteenth century, was not dependent upon experts.

Fry had begun his career as a connoisseur in the Morelli/Berenson mode. He visited Italy in 1891 and 1894 and dedicated his first book on Giovanni Bellini to Berenson. This reveals a young writer for whom the art of the past presented a series of puzzles, to be solved by close attention to gesture, anatomy, and other physical attributes. He had absorbed the Morelli/Berenson message.63 More generally, Fry subscribed to the idea of artistic personalities creating and reacting to cultural fluctuations. His relationship with Berenson cooled in 1903 as a result of disagreements over the latter’s role as adviser to the newly founded Burlington Magazine and although he did not reject his theoretical position as a result, it wasmodified in time by the growing awareness of contemporary art and by the need to develop a more strictly formalist approach – a logical consequence of Berenson’s method.64 Fry was writing in the wake of debates initiated by Moore, MacColl, Meier-Graefe and others. When he penned the essay entitled ‘The Great State’ in 1912, he reaffirmed Moore’s opinions about municipal collections formed along Royal Academy/Chantrey lines.65 By extension, national patronage was no better – nor could too much faith be placed in the philanthropic plutocrat, although the author was softer on this point. The dilemma lay in the system of exchange between artist and patron. The former should be able to protect the ‘free functioning of his creative power’, a gift which should not be bought with money. The artist requires ‘freedom from restraint’, in any modern ‘socialistic’ state.66 The public must accept the need for the ‘symbolic currency’ of art as a means of reflecting upon other types of social relation. Preoccupied with the interaction between symbol and reality, Fry is led further into speculation about art commerce in the ideal state, conceding, as he goes, a place for the revived guilds of the Middle Ages and the opportunity for a ‘large amount of private buying and selling’. In all of this he has moved from what happens at an individual level, towards larger ideals which were never fully articulated, although on the questions of form he was clear. All he could muster as a social theorist was the vague hope that as a result of the ‘levelling of social conditions … people would develop some more immediate reaction to the work of art than they can at present achieve’.67 At the bottom of this lay a British intellectual’s mistrust of emotion and sensuality. The Whistler/Tolstoy dispute remained unresolved, although the evidence of mawkish sentiment lay all around him in Academy painting. The power to trigger the aesthetic experience for him was firmly located in an act of interpretive seeing, in vision, volumes and recession. As he devoted more time to modern French painting, he hoped to discern classic, formalist principles which might satisfactorily explain, in his terms, the railway magnate’s reverie. Readily recognizing that the present was trailing threads from the past, his preoccupation with taxonomy enabled him to affirm the distance between the viewer and the thing he sees. An intellectual gauze screen falls between the viewer and the picture. As he was writing, there were still other possible models for the aesthetic experience and his was only one option within a range of ways of characterizing the effect upon the viewer of a picture. Public reflection and private reverie were, however, both in retreat.