8

The Renaissance of the Imagination

The Duke of Ferrara, a Prince of the Renaissance, discussing with her father’s envoy the dowry of the young woman he hoped to marry, felt compelled to draw back the curtain to reveal the picture of his previous wife. He had commissioned Fra Pandolf to paint her portrait. As the sittings proceeded he had become aware that he was no longer the exclusive object of her attentions and that she showed as much enthusiasm for others as she did for him. Envious, he ordered her death, and ‘all smiles stopped together’. This narrative unfolds as one of Robert Browning’s most celebrated poems, My Last Duchess. In all its circumstantial detail the poem reveals the enduring fascination which the Victorians had for the Italy of Cellini, the Borgias and the court of the Medici. Fra Pandolf’s portrait might be the sort of thing which, following Sir Charles and Lady Eastlake’s tours of Italy in the mid-century, was increasingly collected. The poem is set in the world of the later Pre-Raphaelite painters of the same period, and springs from the ambience of the most celebrated cicerone published by Ruskin, The Stones of Venic. (1851) and Mornings in Florence (1875). Italy in the nineteenth century, as Francis Haskell remarked, was a marvellous museum which existed solely for the pleasure of the English tourist.1

The consciousness of the Italian masters, being acquired during Eastlake’s directorship, from 1855, for the fledgling National Gallery, stimulated the imagination of painters, poets and scholars alike, to the extent that the hostility which greeted the early work of the Pre-Raphaelite painters of the period was swiftly silenced. During the preceding decade, with the Houses of Parliament fresco competitions, a new seriousness had entered British painting. Young painters like George Frederick Watts went to Florence to study, and from the start of their careers were at odds with what Holman Hunt later described as the ‘frivolous art of the day’.2 These were years in which the principal training establishment, the schools of the Royal Academy, shared the same building in Trafalgar Square with the National Gallery and in an important sense the national collection was also a teaching collection. It became essential for young painters like Edward Burne-Jones to visit Italy, a need which was satisfied in 1859 when, as his sketchbook reveals, he was drawn to the work of Botticelli, Carpaccio, Gozzoli and Ghirlandaio.3 John Ruskin’s taste in these years coincidentally broadened to encompass the work of the Venetian painters, a school which was to become increasingly important from the 1860s onwards.4

Constant revival and rediscovery characterizes these years, as young painters searched for styles and subjects which through allegory enabled some form of commentary on the complexity of life. While French critics grappled with theories of realism and the need to be contemporary, they looked on incredulously at English painting at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1855. It had reverted to an archaic style, to copiously studied costume drama in which the conflicts of love and death were played out. Simple confrontations, passionate attitudes, heraldic colour and rich surface patterning emphasized the disjunction between the imagined realm and the dull grey industrial present. Rossetti’s Bower Garden (Fig. 87), an aesthetic imprisonment walled off from the world of conquest, typifies the retreat from reality. The mental lives of those artisans to whom Ruskin addressed his tracts should be one in which the unfettered imagination and the joy of creation flowed happily together. Although he referred to these classes as the ‘mechanicals’, it is clear that Ruskin thought of them as latter day medieval cathedral carvers. As Rossetti’s most vociferous supporter, he stretched to providing financial support which the artist dearly needed. ‘I really do covet your drawings,’ he wrote, ‘as much as I covet Turner’s, only it is a useless self-indulgence to buy Turner’s, and a useful self-indulgence to buy yours.’5 Owning art, a self-indulgence rather than a necessity, could only be justified if it helped to support its producer. Yet deep consciousness demanded access, physical proximity, handling. The ownership of beautiful bowers was both real and imagined.

In the work of the Pre-Raphaelites, early ‘primitive’ naturalism gave way eventually to the rich Venetian colouring which, in the cases of Rossetti and Burne-Jones, came to express the hothouse intensity lying beneath the surface of poems like My Last Duchess. Replete with mythic power Fra Pandolf’s portrait showed the duke’s wife, ‘as if alive’. The eyelid of the posing figure might suddenly flicker, the head might suddenly sway. The sense that this world was so intensely felt that it might indeed be real was addressed in a number of treatments of the Pygmalion myth, in which the beautiful goddess created by the sculptor actually comes alive. Although Burne Jones produced two series of Pygmalion pictures, representations of the story and related images were ubiquitous.6 But these were stiff unsatisfactory attempts to touch something profound, by addressing the independent life of the mind, liberated, floating free of contingent circumstances. The exchange between art and life, between something so intensely seen that it springs from art into everyday life, was a constant motif in literature, painting and sculpture. Beauty lay fundamentally in the way men thought about women. The conflation of the statue or the portrait with the living woman occurs naturally in the mind of Charles Kingsley’s hero, Alton Locke, who, when he falls for Lillian, regards her features as those which have been sculpted by the classical sculptor, Praxiteles.7 She is thus the living embodiment of an ideal woman. When Dorothea visits the Vatican in George Eliot’s Middlemarch, and is gazing at the classical statue of the sleeping Ariadne, she is accosted by the young Will Ladislaw, the man she will eventually marry. The sculpture seems to convey the possibility that Ariadne, as his friend Naumann points out, will be roused to life from her deathlike slumber by the god, Dionysus – something which readers will expect of Dorothea.8

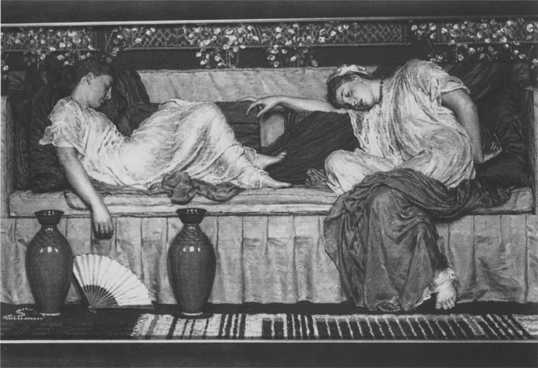

There were many consciously constructed equivalents of the latent beauty of Ariadne in late nineteenth-century art. The sleeping Greek goddess purveyed by artists like Albert Moore was the badge of the ‘aesthetic’ movement. Although the classical, rather than Renaissance, ambience of these works was their defining characteristic, ‘aesthetic’ accoutrements became just as important. It is a painting à la Moore hanging in Mrs Cimabue Brown’s drawing room which the rising young painter, Pilcox, has just completed in one of George du Maurier’s celebrated Punch cartoons (Fig. 88). This shows his patron reclining in classical costume, tired of lilies, trying to smell a sunflower. The marble benches, the loose-fitting garments, the flowers, fans and faience, were all props which, by the 1880s, were readily recognized. These objects were invested with the singular power to summon the world of Tennyson’s Lotus Eaters.

There was, however, a deeper sense in which the works of Albert Moore drew out some innate recoil from the ugly industrialism of the present. Moore succeeded in evolving a highly personal chromatic scale applied to a restricted number of compositional types. The Whistlerian harmonics of the 1860s and 1870s gave way to more brooding, pungent, romantic colouring in the final years of his career. Whilst the ingredients of A Sofa (Fig. 89) were copied by much less talented painters like J. W. Godward, the completeness of his vision easily correlated with that of Burne-Jones, Edward Poynter and Frederic Leighton. These artists slipped easily between classical and Renaissance sources, at times even employing fake Renaissance classical texts. The Renaissance was, to their generation, about the revival of classical learning and its reconciliation with Christian virtues. In his essay on Pico della Mirandola, Walter Pater treated the ambition and the folly of this enterprise. To the modern scholar Pico’s writings and those of the Neoplatonist school

lacked the very rudiments of the historic sense, which, by an imaginative act, throws itself back into a world unlike one’s own … they had no idea of development, of the differences of ages, of the process by which our race has been educated … they were thus thrown back upon the quicksand of allegorical interpretation.

Pater had to concede that, within the ‘madhouse cell’ of the human mind, ‘the allegorical interpretation of the fifteenth century has its interest … its web of imagery, its quaint conceits, its unexpected combinations and subtle moralizing’, but it lacked the depth and integrity of nineteenth-century scholarship.9

There was, in the Victorian admiration of the Neoplatonists, a recognition that in High Renaissance painting ‘Plato and Homer’ might ‘speak agreeably to Moses’. And if the Christian virtues of faith, hope and charity were represented in classical myths, so too it ought to be possible to draw together elements from world cultures and religions into a harmonious whole. Thus it was perfectly possible to argue that the world of ancient Greece was like that of contemporary Japan and that the pagan rituals of Parnassus were somehow equivalent to the delicate ceremony of the cha-no-yu. Whistler argued from this standpoint in his frequently rehearsed Ten O’Clock Lecture of 1885. For two decades he and Albert Moore had happily redesigned the garb of the ancients as kimonos, and although increasingly Whistler stood apart from populist aestheticism in his painting, he was central to it in his personality.10 His ‘aesthetic’ followers might be brigaded together as the Victorian equivalent of what Walter Pater termed the Giorgionesque. It was Pater who provided the most convincing account of these modern tendencies, seen in sixteenth-century terms. These painters, and the way of life they hoped to represent, were searching for ‘the attainment of an ideal condition, this perfect interpenetration of the subject with the elements of colour and design’.11 This was the essence of the school of Giorgione – a group of painters, not yet fully unravelled by connoisseurs – whose communal sensibility expressed ‘ideal instants … from that feverish, tumultuously coloured world of the old citizens of Venice’.12 Vague allusions to social texture conveyed by the term Giorgionesque, in which individual artist identities are subsumed, should not be tossed off as a restatement of the Hegelian or Burchardtian Zeitgeist, without analysing its particular appeal prior to the arrival of ‘scientific connoisseurship’. For a start its inclusivity meant that collectors were embraced as co-conspirators. The ambience of art was as important as the art itself. Authenticity lay initially in achieving the feeling that one was really a Renaissance merchant prince, rather than from the satisfaction that a Botticelli was genuine. Indeed, in some ways, the rigour of the real Botticelli or the real Titian might get in the way and come to dangerously dominate the theatre of art consumption. When the Grosvenor Gallery opened in 1877, its interiors were described as a re-creation of a ‘grand palazzo’.13 Lenders to the first exhibition were all aristocratic collectors who had strong Italian connections. Prominent industrialist collectors of the Pre-Raphaelites, such as William Graham and Frederick Leyland, were often likened to Renaissance potentates because the domestic interiors which they commissioned were modelled upon Venetian palaces.14 In these, contemporary aesthetic and old master paintings hung side by side.

There was no anachronism or inconsistency in this mélange. It was not the ultimate expression of eccentricity – even though Whistler’s decoration of the Peacock Room, for example, has often been presented as the expression of a wayward sensibility.15 The whole attitude to past and present is the backdrop to a collusion between critics, writers, artists and collectors. The winning strategy in Pater’s terms was to remove art from the utilitarian, time-serving values associated with craft production and claim for it the higher ground of abstraction. In his terms the interpenetration of form and subject matter, ‘a condition realised absolutely only in music … the condition to which every form of art is perpetually aspiring’, was found in painting. ‘The condition of music’ has frequently been interpreted in terms of Whistlerian harmonics, in the weaving together of form, space and colour. Ideal form, projected in a mythic space, as a ‘crepuscule in flesh colour and pink’ or a ‘symphony in red’, deliberately devoid of specific reference. There is a further aspect of the condition of music, however, which is easily missed and this is to do with the way music is uniquely perceived. The motif is never fully appreciated the first time a piece of music is heard, but only gradually reveals itself in subsequent performances as it sews itself into the mentality of the listener. The condition of music is one of slow release. Contrary to the common belief that a painting can be seen all at once, and its message instantly grasped, there was now a growing consciousness of the need to expand the frame of reference, to elucidate other purposes, through different levels of reception of the visual. Narration, although it was only one very limited way to claim the attention of the spectator, and in Whistlerian terms had little to do with aesthetic experience, remained richly suggestive. Pater could contend that the highest form of dramatic poetry presented profoundly significant instants – ‘a mere gesture, a look, a smile perhaps – some brief and wholly concrete moment – into which, however, all the motives, all the interests and effects of a long history, have condensed themselves, and which seem to absorb past and future in an intense consciousness of the present’.16 It was in this moment of ‘gem-like flame’ that the beautiful statues of Galatea and Ariadne came to life.

There was, nevertheless, a danger that the life which was claimed, the conferring of ‘reality’ upon contingent phenomena, could easily be lost. Orpheus’s hold on Eurydice in Poynter’s early rendition of the theme (Fig. 90) will be broken and she will sink back into the underworld. He will wander distracted through the world and fall into the bacchic orgy of the women of Ciconia who will tear him limb from limb. His disembodied head will float down the Hebrus still singing of Eurydice after death. By the time Whistler was delivering the sermon of aestheticism in 1885 it was already too late. Many of the stronger British artists had been wooed away from this world of dreams into that of contingent circumstances in the more literal problems of naturalism and Impressionism. Followers of Burne Jones like Evelyn de Morgan, Spencer Stanhope and John Melhuish Strudwick were left palely loitering in his shadow. All of the aesthetic and Symbolist impedimenta were there in their work but none of the passion. Arguably they lacked conviction because they were so far removed from the world of literal appearances. Painters sought correlations between the natural world and that of the spirit. Writing about ‘The Aims of Art’, George Frederick Watts alluded to this sense of the richness of moods and memory acting upon lived experience in the artist’s mind. ‘Perceptions and emotions,’ he declared,

are shut up within the human soul, sleeping and unconscious, till the poet or the artist awakens them. Nature is full of similes – symbols and parables to the eye of faith, poetic suggestions to the poetic sensibility. Where the expression of these is vague, as in music, the utterance will be differently construed, and in the art that would be suggestive rather than representative of material fact, very various emotions and definitions may be conveyed.17

Here, for the younger generation, penned by the ageing outsider of English painting, was an eloquent re-statement of Baudelairean correspondances, leading the painter into the search for that which was purely suggestive. The artist was looking for a talisman, an object which would contain more than itself, which would have grafted on to it ideas and emotions, a past actual and imagined. The human image itself might exert symbolic power, equivalent to Fra Pandolf’s portrait or the picture of Dorian Gray.

Pater had initially been nervous about proposing a doctrine which depended upon intense but fleeting sensations. The decadents who followed him were those for whom the thirst for experience led to intemperate and sometimes anti-social acts. The credo of Marius the Epicurean was to grasp at ‘exquisite passion, or any contribution to knowledge that seems by a lifted horizon to set the spirit free for a moment’.18 But free from what and aspiring to what? From contingent circumstances into the life of the mind? Pater found no immediate need to be explicit on these matters. Their vagueness lay around in the fabric of aesthetic experience. It was urgently necessary for the artist to lead his or her audience out of quotidian realities as the painters of the school of Giorgione had done. What was there in contemporary art which answered to this criterion?

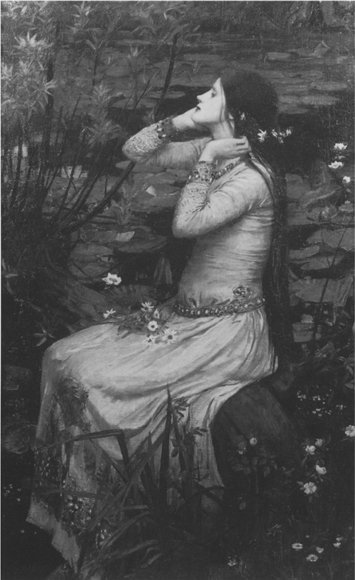

These ideas were played out in the ripples of Pre-Raphaelite revival throughout the 1880s and 1890s in the work of John William Waterhouse, Thomas Cooper Gotch, John Liston Byam Shaw, Frank Cadogan Cowper, and in the formation of arts and crafts exhibition societies in London and the provinces. They continued with even greater naturalistic intensity, affected by the presence of photography and the challenge posed to visual authenticity by combination printing, in the second half of the nineteenth century. There were intense debates about naturalism itself, emanating from the work of the French painter, Jules Bastien-Lepage. Jeanne d’Arc écoutant les Voix, exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1880 and again in 1889, a naturalistic history painting studied in detail in a garden with a live model, also contained the spirits of St Michael, St Catherine and St Margaret as real presences.19 In the process of depiction, the naturalist painter conferred reality upon contingent circumstances. Could a painter standing by his easel in an orchard, in black serge trousers and white starched shirt, his fashionable dove grey tie held in place by a single pearl – could such a man of the present see spirits? Conclusively, whatever the theoretical contradictions might be, he had. And therein lay the challenge to post-Darwinian materialism.20 Henceforth the mere look of a Jeanne d’Arc figure might suggest more than what was literally being represented. A ‘Lady of Shalott’ or an ‘Ophelia’ might do the same. And although these issues should not be limited to stylistic convergence, the absorption of Pre-Raphaelitism into internationally accredited Salon naturalism gathered pace with the inclusion at the Royal Academy in 1888 of John William Waterhouse’s The Lady of Shalott (Fig. 91). If critics were initially apprehensive about this treatment of an Arthurian subject – previously the property of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt, and now given ‘the cool open-air unity of French naturalism’ – they were won over, as Waterhouse absorbed foreign influences and quickly moved on.21 It was not, however, a matter of borrowing so much as defining new sets of possibilities, as new artist constellations momentarily glowed in the firmament. Annual exhibitions now sought to ‘feature’ new groups and movements, as when, in 1890, the painters of the Glasgow School showed by invitation at what was to be the last of the Grosvenor Gallery exhibitions.22 Amongst their offerings was an almost unclassifiable picture, The Druids Bringing Home the Mistletoe (Fig. 92), a joint production by George Henry and Edward Atkinson Hornel. Not only were such collaborations unusual, but this colourful procession of shamanistic figures, complete with gold enamellings, challenged London sensibilities.23 For Walter Armstrong it was simply ‘the most daring performance they have sent’.24 Although they could not define it, forward-looking critics recognized something new and progressive in the picture. Far from being a stale, re-heated recapping of familiar Pre-Raphaelite tropes, it was a modern treatment of ancient British legend and ritual, carrying to a logical end the formal characteristics of the classic rustic naturalist mise-en-scène. Henry and Hornel’s figures zigzag down the hillside to confront the viewer, mimicking the familiar compositional codes of paintings of peasants in the 1880s.25 The effect was to flatten the picture surface and accentuate decorative effects through the use of Celtic embellishments and bright colours.26

92 George Henry and Edward Atkinson Hornel, The Druids Bringing Home the Mistletoe, 1889

The Druids was a manifesto statement, seen, deciphered and reinterpreted almost immediately in Alexander Roche’s The Court of Cards, 1891 (Fig. 93), a work described as ‘a lovely piece of artistic nonsense’.27 These were not Pre-Raphaelite pictures, but they opened the way to an international ‘consensual’ form of painting derived from the Bastien-Lepage school, and extended most obviously in the work of Frank Brangwyn. The unresolved position of the Pre-Raphaelites was an ingredient in this confluence. Many erstwhile Paris-trained plein-air painters turned away from the contemporary scene, and with his second versions of The Lady of Shalott and Ophelia in 1894 Waterhouse engaged more closely in the reshaping of Pre-Raphaelitism. Between Millais’s Ophelia and Waterhouse’s (Fig. 94) the entire development of psychoanalytic theory, led by the writings of Jean-Martin Charcot, had occurred – and with the investigation of trance-like states. That women were now accorded greater freedoms is somehow captured in a robust figure which one critic saw as a ‘strong reading of character’.28 It was here that the tension between the principles of naturalism and the imaginative act of envisioning a scene from literature began to boil over. For George Moore, this Ophelia could not lift herself out of the present. The picture was ‘a vulgarity of Tottenham Court Road manufacture’.29

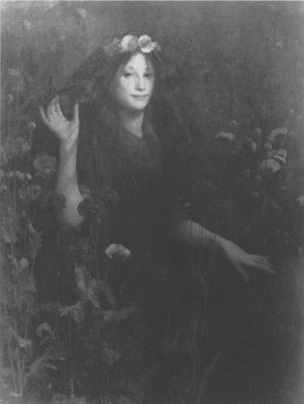

The assumed restrictions on naturalism were now lifted. Former Cornish naturalists like Thomas Cooper Gotch, Marianne Stokes and Elizabeth Forbes had, by 1895, all but abandoned the painting of fisherfolk.30 Serious questions could now be posed, however, concerning the values, the moral conflicts, the blighted loves and the religious purposes which were embedded in the Gothic, quattrocen-to and Venetian stylizations of the Pre-Raphaelites.31 The remarks attributed to Boldini at the opening of the Fair Women exhibition hold true.32 Modern British painting must have seemed, to foreign outsiders, a miscellany of archaic styles, the continued adoption of which, after 1880, was absurd and confusing. The British reverted to conceptual frameworks which had had their day. Cornish painters, emerging from a background which had favoured objectivity, moved to literary themes of divine love or fatal beauty literally, as in Stokes’s Angels entertaining the Holy Child, 1893 (Fig. 95), or Gotch’s Death the Bride, 1895 (Fig. 96). Moments of spiritual intensity are translated into tableaux vivants. Thus the frightening naturalism of Death the Bride outweighed its improbability. Gotch’s turning to ‘symbolism and decoration’ was interpreted as a deliberate retreat into a world of artifice.33 The poppies and the dark wood through which the pale figure floats referred to inner longings of the human soul. Philippe Julian observed that the enigmatic smile of Gotch’s Death recalls that of the Gioconda – a picture which for Pater exercised mystic power.34 In a celebrated passage he wrote, ‘She is older than the rocks among which she sits; like the vampire, she has been dead many times, and learned the secrets of the grave’; a ‘trafficker’ in Eastern webs, a ‘diver in deep seas’, a fusion of Leda and St Anne, all history and culture are to her ‘but as the sound of lyres and flutes’.35 The painting of today, the 1890s, should be able to release an equivalent potency. Today’s collector should be like Browning’s Duke who wisely protected his visitors from the aura of Fra Pandolf’s portrait by suspending a curtain in front of it.

The case for a new naturalistic Pre-Raphaelitism was strengthened by the sudden appearance in 1896 of a picture which reconciled that need for decorative and dramatic effect in historical drama. This was Edwin Austin Abbey’s Richard, Duke of Gloucester, and the Lady Anne (Fig. 97), the work of an artist known primarily up to this point as an illustrator. Pictures like this, not apparently dependent upon the contemporary experience, demanded a novelist or playwright’s imagination. The scene on the page had to be lifted from the literary source and seen in the mind’s eye. It had to be imagined and restaged in a succession of sketches and studies which educated the brain into what it was seeing, and that realization was planned process. When it was shown at the Royal Academy, Richard, Duke of Gloucester took painters and public alike by storm. It derived from the theatre and it played back into the theatre. Abbey was grounded in the admiration of Bastien-Lepage: to him as a young man, Jeanne d’Arc was ‘the very greatest picture ever painted by anybody since the fifteenth century’.36 Although preoccupied with documentary accuracy, for which Shakespeare provides the raw material, Abbey, an American expatriate, opened up to the imagination of the masses the grand spectacle of the national past. The Art Journal hailed the author of Richard, Duke of Gloucester as ‘one of the artistic surprises of the century’.37 Visual drama of colour and costume supported the drama of the moment in which the evil Richard attempts to woo the Lady Anne. The Athenaeum summed it up as ‘the most powerful spectacle in the Academy’.38 The painting was spectacular. Its effect, before touching critics and the public, reached out to art students like John Young Hunter. He recalled being taken to Abbey’s studio, where ‘His picture Richard, Duke of Gloucester, and the Lady Anne, was just finished. The memory of this occasion is still vivid [Young Hunter’s recollections were written late in life, he died in 1955]. I was literally spellbound, and for several years my appreciation, my enthusiasm, showed in my own painting even to the extent of imitation.’39 As with Henry and Hornel, Abbey’s colour was emblazoned on to the canvas, and where they looked to Celtic design, he made appropriate, archaeologically correct use of heraldry.40 His effect upon the younger generation like Byam Shaw, Frank Craig, Frank 0. Salisbury and the Young Hunters was immense.41

95 Marianne Stokes, Angels entertaining the Holy Child, 1893

97 Edwin Austin Abbey, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, and the Lady Anne, 1896

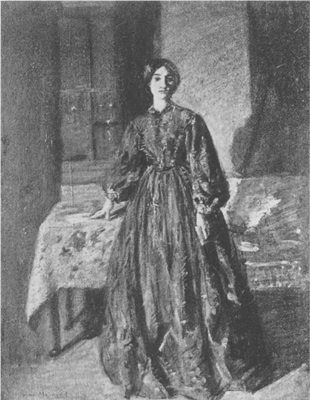

Dramatic confrontation, drawing in emotions of love, fear or spiritual ennui, was, by the second half of the 1890s, the subject of numerous Academy pictures. The passionate dilemmas of star-crossed Renaissance lovers remained a consistent source of subject matter, particularly as contemporary taste moved back to the re-evaluation of the Pre-Raphaelites. In Frank Dicksee’s An Offering, 1898 (Fig. 98), for instance, a young man in sixteenth-century costume leans forward holding a small statue to his lady. The bibelot is a bound cupid, ‘love’ imprisoned, symbolizing the ultimate failure of the young man’s attentions. Although there is no specific source for An Offering, the work evokes the dramatic monologues of Robert Browning whose reputation had grown enormously in the ten years after his death. In Dicksee’s painting we enter the world of rich Renaissance embosses, of symbolic trinkets, of theatrical gesture, of love, betrayal and deceit, the world of a poem like My Last Duchess.42

With Dicksee, in the 1890s, Pre-Raphaelite romanticism embraced those who were well entrenched at the Academy. Why did this occur? The answer lies partly outside painting, in other aspects of intellectual exchange which have already been summarized. At the end of the century, Baudelairean correspondances flow side by side with Walter Pater’s aesthetics and the world of appearances was now commonly believed to be only a mirage, a ‘forest of symbols’ behind which ‘perfumes, sounds and colours answer each to each’.43 Consciousness of the ‘deep oneness’ in Charles Baudelaire’s poetry was conflated with Pater’s belief that all art ought to aspire to the condition of music. There should, in other words, be some background abstract unity, Baudelaire’s ‘oneness’, only to be perceived in the intensity of the moment. Liberating the senses in ‘one desperate effort to see and touch’ was the artist’s goal.44 Creating the tension between ‘surface and symbol’ led painters through naturalism, through sharply focused reality, into the enchanted world of legend.45 In this regard the rereading of Robert Browning, who died in Venice in 1889, was essential to the making of poetry in the 1890s. Browning, particularly for his monologues on artist life in the early Renaissance, was regarded by Ruskin as ‘unerring in every word he writes of the middle ages’. His use of local colour set him above Tennyson and Rossetti at the time, and there was an agreeable air of decadence and waste in Andrea del Sarto and Fra Lippo Lippi, the secondary painters he selected as his subjects.46 The interest in the school of Raphael and the school of Botticelli which these represented coincided with the contemporary controversy initiated by Bernard Berenson at the New Gallery old masters exhibition in 1895. Nevertheless the sense of local colour used to authenticate appearances was not enough in itself. Comparing Browning’s poetry with Pre-Raphaelite painting, an essayist in The Scottish Art Review, within months of his death, commented upon the danger of ‘executive ability usurping the place of fine imagination’. The critique continued, ‘but Andrea del Sarto exemplifies the important truth that a painter’s work will be really great in proportion as the artist himself is great in mind and character’.47 In other words, it was not simply a process of honing skills. Mind now took precedence over matter and the nuances inferred in Browning’s monologues remained entangled with the discussion of the Pre-Raphaelites as a new generation of ‘decadent’ and Celtic revival poets emerged.48

However, at the time when Dicksee’s painting was produced, there were even more urgent reasons for reconsidering Pre-Raphaelitism, prompted by the deaths of Ford Madox Brown in 1893, of Millais and William Morris in 1896, Burne-Jones in 1898 and Ruskin at the beginning of 1900. This reassessment was supplied by Percy Bate’s The English Pre-Raphaelite Painters, in 1899. Although little more than a survey, produced for popular consumption, Bate’s ambition, not explicitly declared, is expressed in the scope and structure of his account. He wrote from the conviction that, ‘The ripples of the agitation started by the formation of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood are still sweeping on, and widening as they go … and accordingly the movement is more diffuse and less marked than in its early and more vehement days.’49 More than many subsequent writers, Bate attempted to be comprehensive and inclusive, referring to Scots and Liverpool painters and incorporating artists like James Tissot into his scheme. He devoted a lot of attention to what he termed the ‘Rossetti Tradition’, and saw Rossetti’s influence in painters as diverse as Whistler, Maris and Steer.50 So comprehensive was the case presented that reviewers of Bate’s book quickly conceded that ‘no contemporary school of painting, no modern movement in art’ throughout the world was untouched by Pre-Raphaelitism. There may be some speculation that the current revival was in part motivated by ‘a revulsion of feeling from the extravagance of impressionism’, but this did not detain confident proponents of the movement like Bate.51 The author was guarded about young contemporary painters who were part of this trend, but he was prepared to name a few – principally the rather unimaginative followers of Burne-Jones, like Strudwick, Spencer Stanhope and Evelyn Pickering. It was with the arrival of Aubrey Beardsley, Charles Ricketts and Charles Hazlewood Shannon and, more critically, with the mature work of Brangwyn, Abbey and Waterhouse that new life was breathed into this strand of late Victorian art. In essence these groups represented the polarities of Pre-Raphaelitism which Bate noted, but did not regard as irreconcilable.52

99 Eleanor Fortesque Brickdale, The Deceitfulness of Riches, 1901

It was in this context that the debate about the direction of British painting around 1900 was held. A retrospective of the work of Madox Brown had been staged at the Grafton Galleries in 1897. In 1898 the Royal Academy held its winter tribute to John Everett Millais, its recently deceased President, with an exhibition of 242 works, many of them the favourite early Pre-Raphaelite pictures, accompanied by a descriptive catalogue hastily prepared by the editor of The Magazine of Art, M. H. Spielmann.53 Simultaneously the New Gallery winter exhibition was devoted to the work of Rossetti. Within the next two years, John Guille Millais published his father’s biography and H. C. Marillier his record of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. In 1900, Philip Burne Jones staged a show of his father’s unfinished canvases in the garden studio at the Grange, West Kensington, and Spielmann devoted the April issue of The Magazine of Art in 1900 to an assessment of the place of John Ruskin, with particular reference to his current relevance.54 Although ostensibly celebrations, it is difficult not to read the plethora of publicity for the Pre-Raphaelites around 1900 as a concerted attempt to re-invent an accredited form of Englishness. What mattered was the totality of the phenomenon.

Bate’s synoptic view of ‘Pre-Raphaelitism Today’ could not disguise the seeming contradiction between those who followed Millais’s early naturalism and those in the Rossetti camp. Young artists moved freely from one camp to another. The more recherché mannerisms of Rossetti were as likely to appear in the Academy as elsewhere. Beneath the paint film there was in essence a constant rerun of the debates initiated by Browning’s poetry and a replay of the Wildean tension between surface and symbol. How much local colour and circumstantial detail was necessary to support the idea which the picture hoped to convey? There is a sense of the volatility of opinion in a conversation in which The Studio magazine’s ‘lay figure’ locks horns with a ‘decadent poet’ on the recent retrospectives of Millais and Rossetti,

‘It is just because the younger generation are apt to think that the latest Rossetti’s, and Mr Aubrey Beardsley, represent each pole of the Pre Raphaelite ideal, that it is most fortunate that they should have the opportunity to study the real meaning of those who coined the expression Pre-Raphaelitism – a synonym for realisation, verification, materialisation, as Ruskin put it.’ ‘You mean to say that Pre-Raphaelitism once was sheer realism,’ said the Decadent Poet, ‘I thought Millais only became realistic when he grew rich, and that Rossetti was always intense.’

As the discussion continues, it is clear that while the early realism of both painters is applauded, Millais in particular – ‘the Millais we reverence in Mariana, The Woodman’s Daughter, The Huguenots … did his best to be factual and to insist upon realistic details of his subject, even if they jarred upon its poetry’.55

This fictional conversation contains authentic contemporary voices. Decadence in poetry and prose associated with Wilde, Arthur Symons and the publisher, John Lane, had its counterpart in the imperialist club-swinging anti-decadents who congregated around William Ernest Henley at the National Observer and the New Review. As a number of writers have pointed out, there were key figures like the young William Butler Yeats who were associated with both groups.56 In painting, this same dichotomy could easily fall between the followers of Rossetti and Burne Jones and the athletic moor-stalkers who followed Millais. Yet, as in poetry, it was not so simple. James Liston Byam Shaw’s Silent Noon for instance, shown at the Royal Academy in 1894, combines a Rossettian theme with the naturalistic detail associated with Millais and Waterhouse.57 In Eleanor Fortesque Brickdale’s The Deceitfulness of Riches (Fig. 99), shown at the Royal Academy in 1901, there is the same tension between early Pre-Raphaelite detail and late Rossettian intensity.58 However, the most obvious engagement with these oppositions lies in the early work of Mary Young Hunter whose The Denial, 1901, is overtly Rossettian, whilst her Roadmender, 1903, and The Bow in the Cloud, 1906 (Fig. 100), are heavily dependent on Brett and Millais.59 This vacillating emerged from the implicit challenge to mid-century morality mounted by writers and intellectuals. What remained of naturalism was the capacity to switch styles as the occasion demanded. As H. G. Wells declared, ‘from the middle of the century onward this assurance of the prosperous British in the world was being subjected to a more and more destructive criticism, spreading slowly from intellectual circles into the general consciousness’.60

By the early years of the twentieth century, references back to the art of the mid-Victorian period, the time of rapid industrial growth, high farming, imperial expansion and Christian philanthropy, had become commonplace. The illustrators of the 1860s enjoyed a revival amongst the followers of Henry Tonics at the Slade School of Fine Art and there was an attempt to revisit aestheticism in the mural manner of Frederick Cayley Robinson, Charles Hazlewood Shannon and Gerald Moira. Even New English Art Club painters like Philip Wilson Steer and David Muirhead (Fig. 101) looked back to the mid-century for an understanding of the present and this was consonant with the revival of fairytale and legend in Edwardian literature. In Muirhead, however, the vital context of religious observance and the plight of the working woman have been mislaid in vague allusions to lost love – and the sense, only truly possible in the post-Pre-Raphaelite era, that these ingredients, a cottage interior, Windsor chairs, a sweet young woman in a satin dress with a full skirt, her hair coiffed in the style of the 1840s, were of themselves beautiful. Social purpose has gone. In its place there is merely proof of the English resistance to change what had once been considered good.61 It was this mélange to which Baldry was referring in 1903 when he defined the ‘new’ Pre-Raphaelites.62

These recondite references are not merely stylistic or art historical. They refer to the resuscitation of cultural values and origins which carry within them a renewed search for a lost innocence which was the more urgent as, after the death of Queen Victoria and the ignominies of the Boer War, the Empire slipped towards crisis. The first thought that these new Pre-Raphaelites presented, the exciting possibility that going back to roots might produce some fresh understanding, quickly faded. Brickdale, Byam Shaw, Salisbury, Craig, Cadogan Cooper all became costume pageant painters whose modernity was confined to an occasional heraldic flourish. In the criticism of the Young Hunters, there was unease about the reinvention of Pre-Raphaelitism.63 These new Pre-Raphaelites were working in a world in which the characteristics of patronage were different from those of their predecessors. Worldly Edwardian financiers and middle-class professionals – judges, academics, publishers and the like – had now replaced self-improving provincial industrialists as collectors. Small pictures were produced for dealers’ solo exhibitions, designed for small patrons. Materialist values supplanted spiritual ones. Ruskin’s ‘mechanicals’ of 50 years ago had first formed unions and now, the Labour Party. The ‘new’ Pre-Raphaelites’ claustrophobic intensity anticipates the animated tableaux of silent cinema. By 1908, it was no longer possible to talk about them outside the pages of popular low-brow magazines. The moment had passed.

The pace of change can be gauged by the willingness of critics to propose viable alternatives. D. S. MacColl, surveying nineteenth-century art in 1901 as a proponent of Impressionism, consigned Pre-Raphaelitism to the unexplainable residuum. Rossetti, the forerunner of the most extreme manifestation of the current Pre-Raphaelite tendency, was ‘fortified by literature’. He ‘turned into the fields of painting like a child … Parts of a figure remain doll-like or manikin; a body is seen by its eyes and lips and hair and hands, and its spirit of gesture, in an order moulded on desire and purpose.’64 He and his following were wilfully cut off from the mainstream of painting, as it had emerged in the late nineteenth century.

Eight years later, when the young modernist critic, Frank Rutter, was commissioned to write a short monograph on the painter, there was a clearer critical perspective on Rossetti’s ‘flaws’. Rutter had a wealth of information before him and his book is a workmanlike account, exposing in some detail the haze of whisky, chloral, morphia, ether and bromide into which the painter/poet sank in the last years of his life. ‘Fate did not permit him to produce the perfect, flawless masterpiece’, and he would be remembered as a personality ‘for his revival of Symbolism in are.65 This was the ‘Rossetti tradition’, and it had dissipated through numerous European schools and sub-sets. The syntax had begun to be clear, and as Pre-Raphaelitism continued in minor ripples through the early work of Paul Nash and Stanley Spencer into the painting of the neo-romantics, it was for its upholding of the literary and the visionary as a means to achieve the imaginative restructuring of experience that it would be valued.

103 Jean-Antoine Watteau, Gathering in the Park with a Flautist, 1717