The full cross-cultural story of European theatrical engagements with evolution is far too broad for in-depth discussion here, but I look at several playwrights whose works reflect a serious interest in evolutionary themes and signal the potential of theatre to explore them. The first is Swedish playwright August Strindberg, whose interests in science, and in evolution particularly, set a key precedent for later playwrights such as Bernard Shaw, Thornton Wilder, and Susan Glaspell. My purpose here is threefold: to see what playwrights across different cultures were doing with evolutionary ideas (especially in comparison with Ibsen, who influenced so many dramatists), to set Shaw’s work in relation to all of these, and to gauge the extent to which ideas about breeding begin to dominate theatrical engagements with evolution at this time.

In contrast to Ibsen, Strindberg had an overt and well-documented interest in evolution, expressed in many of his non-theatrical writings; unlike Ibsen, and very like Shaw, he took great trouble to lay out his views as clearly as possible. He was, like Charles Darwin, a transformist, but he also embraced the mystical side of evolution implicit in Ernst Haeckel’s monism.1 In 1870, as a student at Uppsala, he would visit a friend who was studying the sciences to “peer through his microscope and learn about Darwin.”2 His scientific studies took in everything from “Darwin to the occult, from Naturalism to Supernaturalism, from physics to metaphysics, from chemistry to alchemy.”3 In one book of essays alone (or, as he called them, “vivisections”), he touched on the “zoology” of women, racial stereotypes, Maurice Maeterlinck, and other topics; then, in the collection Jardin des Plantes, he wrote substantially about natural history.

Strindberg’s engagement with evolution changed drastically over the course of his career. In his naturalistic phase, in the 1880s, he approaches playwriting as he approaches science, depicting characters “in terms of the survival of the fittest, natural selection, heredity, and environment” and calling his play Miss Julie (1888) “a simple scientific demonstration of the survival of the fittest” in which the male is shown to be the fittest.4 The play shows, in characteristically misogynistic fashion, the catastrophic results of female sexual selection. After naturalism comes Strindberg’s “inferno phase” (1892–1898); during this period, he sees science as the highest calling and urgently explores what he perceives as a tension inherent in nature “between chance, coincidence and discontinuity, on the one hand, and order, relationship and coherence, on the other.”5 One essay, “The Death’s Head Moth,” proclaims “the role of chance in the origin of species!”6 Another, “Indigo and the Line of Copper,” provides a highly technical chemistry discussion followed by the conclusion that “this is the unity of matter made manifest, and the doctrine professed by every modern scientist since Darwin, although a goodly number have recoiled from the consequences.”7 But, by 1907 (when he finds religion again), he denounces evolutionary theory as “unscientific rubbish” along with contemporary science generally and is heavily criticized for it.8

There is a tendency to regard Strindberg’s “inferno” phase as an aberration, a somewhat embarrassing parenthesis between the two major creative phases of his career (naturalism and expressionism/modernism) in which he loses his sanity and does futile alchemy experiments and nearly kills himself in the process. Yet his essays show how important Strindberg’s scientific writings and experiments were for him as a creative process, how central this phase was to his work and how far it informs his thinking more generally.9 In one typical example, “To the Heckler” (1896), he asks: “Has not the cyclamen shown you that all botanical systems are arbitrary and vain, and that nature does not create according to a system? . . . Enlighten me and all the other people who believed that the exact sciences do not work with fictions and fantasies.”10 He believes the key is combining imagination (arts) and the purely animal world (sciences). He is, at this stage, a true interdisciplinarian.

Strindberg had several ambitious projects in different genres that show how he conceived of evolution on a vast cultural as well as physiological scale. He planned—and, indeed, wrote the first three plays of—a “cycle in forty-five acts” depicting world history.11 He also planned a huge book in 1895 that would encompass all of evolution; his letters give a detailed description of its proposed contents, beginning with “searching out the primal elements of the world,” then descending into the oceans to observe life emerging from the water, ascending into air to explore the atmosphere, then returning to earth to track the development of life from the moment when plants and animals first parted ways to the arrival of man.12 These epic projects indicate an interest not only in the mechanisms of evolution but also in its mode of progression; he seemed to see history’s course as saltationist and catastrophic rather than gradual, moving “with glaring surprises and violent jumps, proceeding relentlessly and with a certain lack of feeling for mankind’s suffering. . . . [It is] in keeping with nature’s insensitive method of employing thousands of years to form a geological strata, only to break up and recast what it has made.”13 Here again is the familiar rhetoric of the Victorians that nature is insensitive, indifferent, cruel. These vast projects also look forward to Shaw’s and Wilder’s use of epic in Back to Methuselah and The Skin of Our Teeth respectively in order to stage the whole of human evolution.

Along with his born-again faith, what finally turned Strindberg from Darwinian evolution was the fear of reversion or retrogression. He addresses this in his essay “Whence Have We Come?” which was published in Vivisections II (1894) and marks a distinct aloofness to Darwin; by 1907, with A Blue Book and its three sequels (1908–1912), he is fully anti-Darwinian. “So, we come from heaven, and descend towards the anthropomorphs. Is life then evolution backwards?” The “true end of life” seems therefore to be “an ape . . . so much trouble just to become an ape!”14 He expresses the same thought in “In the Cemetery” (1896): How could the beautiful child before him, so angelic, be descended from an ape? Yet he could believe that an old man is. “Progress backwards, then, or what? . . . Are we the degenerate offspring of those blessed ones, whom we can never forget?”15

Strindberg also had trouble accepting extinction as a concept. In “The Death’s Head Moth” (1896), he imagines a child asking where the light goes when a candle is blown out: “In the last century scientists would say that it returns to the primary light from whence it came. Our scientists, who pronounce energy indestructible, nevertheless say that it has ceased to exist! Ceased to exist, to be perceived? But nothing can cease to exist.”16 By 1903, in “The Mysticism of World History” (echoing Haeckel’s recently published The Riddle of the Universe and Shaw’s Man and Superman, performed the same year), he is positing a Schopenhauerian “Conscious Will” in history, not just a random and chance set of events but an Ur-pattern.17 He derides the “Darwin monomania” that he detects everywhere which for him means a cultural obsession with heredity.18 He embraces telegony, an alternative to biological heredity; the term, meaning “offspring at a distance,” was used by August Weismann in 1892 to describe instances of the phenomenon of psychic heredity.19 As Marvin Carlson has shown, Strindberg wove this idea of the heredity of influence into his plays, as did Ibsen in The Master Builder.20

On the one hand, Strindberg managed to engage with a wide range of evolutionary themes, beyond the preoccupation with heredity that dominates his contemporaries.21 On the other hand, his trajectory is that of so many of his contemporaries: moving from a firmly Darwinian stance to a rejection of natural selection in favor of a mystical, monist vision. This makes Anton Chekhov all the more exceptional. He “liked Darwin terribly” and said in 1894 that science was “performing miracles everyday.”22 Chekhov had a “strong but sensible” faith in humankind; he was a doctor, a firm materialist, interested in the earth beneath his feet and the natural order, saying in 1889, for example, that “outside of matter there is no experience or knowledge, and consequently, no truth.” He relished many fields of inquiry, including sociology, zoology, gardening, psychiatry, and the philosophy of science.23 Downing Cless argues that “natural stakes are present in each of Chekhov’s four major plays,” such as the “nostalgic affection” for the cherry orchard vying with “eco-hubristic” entrepreneurship.24 He also notes the odd mixture of people in Chekhov’s plays, their “unrelated relatedness”: “They are put together like random species” whose ability to survive is not easy to predict.25

Like Strindberg and Chekhov, the French avant-garde playwright Alfred Jarry was biologically inclined and well informed. Rae Beth Gordon contends that Jarry’s interest in biology, natural history, and evolution was the “cornerstone” to his thought and that it is “the most important, but unexplored, key to understanding the Ubu cycle.”26 Jarry—who played the Troll King in the French premiere of Ibsen’s Peer Gynt, in the same year and same theatre as Ubu’s premiere—was fascinated by the concept of the biological hybrid, especially by the idea of the missing link (for him the ultimate and elusive hybrid, the bridge between man and animal). Like so many avant-garde theatre practitioners, he was interested in the frontier between human and animal and between human and machine, the idea of what it is to be human in a rapidly changing modern environment. Gordon argues that Ubu is a hybrid that Jarry thought of even before he read Haeckel and began to consider himself a naturalist, and in Ubu Roi, Jarry created “a hybrid form of theater, at once popular theater and avant-garde,” fusing Shakespeare’s Macbeth, Jacobean revenge tragedy, Grand Guignol, and abstract art.27

Of a completely different dramatic stripe was Jarry’s contemporary Eugène Brieux, once “the most popular dramatist in France,”28 whose fans in the English-speaking world included Shaw, H. L. Mencken, and St. John Hankin. In his sustained theatrical exposé of social problems, Brieux shows particular concern with sexual health and with the roles of women in society and in nature. He deals with sexually transmitted disease, abortion, infant mortality, and other reproductive issues, showing them as the result of ingrained and often-corrupt societal systems that adversely affect women. Les Trois Filles du M. Dupont (The Three Daughters of Mr. Dupont, 1897) exposes the damage done by the dowry system; Le Berceau (The Cradle, 1898) deals with divorce; Les Remplaçantes (The Wet-Nurses, 1901) shows the tragic repercussions of the corrupt wet-nursing system for women and babies and for the nation as a whole, in the grip of a low birth rate. This crisis prompted an urgent national debate for many years, in which artists, doctors, playwrights, and politicians alike participated: Brieux; Clémence Royer, Darwin’s first French translator; Henri de Rothschild, doctor and dramatist; playwrights François de Curel and (in satirical mode) Guillaume Apollinaire. Stepping up his intervention, Brieux’s most famous play, Les Avariés (Damaged Goods, 1901), deals with syphilis acquired by men visiting prostitutes and shows its devastating consequences for the family; Maternité (Maternity, 1903) pleads the necessity of birth control; Simone (1908) “denies the right of a man to kill his wife for adultery,” while Suzette (1909) “promotes the rights of mother and child.”29 These are just a few of his plays; Brieux was hugely prolific, and Shaw strenuously promoted his work in Britain, yet he has all but dropped off the theatrical radar. His plays are rarely revived or discussed, some are still unavailable in English, and there is no biography of him in English.30 Both Mencken and Arnold Bennett had reservations about his work that may help to explain this subsequent neglect: “Violent reformers,” wrote Bennett, cannot be serious dramatists.31

Shaw Re-creates Evolution

Shaw complicates Bennett’s easy assertion, producing by far the most thoroughgoing and innovative theatrical engagement with evolution after Ibsen. Ibsen’s plays—“steeped in the gloom of mid-nineteenth-century science”—furnished Shaw with dramatic inspiration for characters and situations as well as modeling how to use science as a theatrical foundation.32 Yet Shaw created a completely different dramatic idiom, full of inventiveness, wit, debate, stylization, and overt metatheatricality. He combined a deep devotion to Ibsen with an equally profound antipathy to evolution by natural selection, epitomizing the contrarian position demonstrated by so many of his theatrical contemporaries (despite William Archer’s stinging claim that Shaw’s “great intellectual foible is credulity”).33 He lamented that Ibsen’s plays show “no trace . . . of any faith in or knowledge of Creative Evolution as a modern scientific fact.”34 In other words, Ibsen’s only flaw is that he is not a Shavian.

Shaw rejected the Malthusian harshness of Darwinian natural selection; he had a “natural abhorrence of its sickening inhumanity.”35 He repeatedly objected that natural selection “explained the universe as a senseless chapter of cruel accidents.”36 This reaction was a “characteristic scientific aberration” that Shaw explained “with admirable lucidity and wrongheadedness” in the preface to Back to Methuselah.37 Dismissing the idea that “Darwin invented Evolution,” Shaw’s plays consistently endorse non-Darwinian evolution.38 Influenced by Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche as well as by Buffon, Lamarck, Samuel Butler, and Herbert Spencer, Shaw believed in the role of the will in human evolution. Creative Evolution is his name for Lamarckian evolution, or functional adaptation. The idea “underlies almost every one of [Shaw’s] major plays,” and his works have an “underlying unity” through their sustained commitment to it.39 He gave a trenchant account of his views in a letter of 1907:

I believe that all evolution has been produced by Will, and that the reason you are Hamon the Anarchist, instead of being a blob of protoplasmic slime in a ditch, is that there was at work in the Universe a Will which required brains & hands to do its work & therefore evolved your brains & your hands. I have the most unspeakable contempt for Determinism, Rationalism, and Darwinian natural selection as explanations of the Universe. They destroy all human courage & human character; & they fail utterly to account for the most obvious facts of life.40

Shaw explains in his preface to Back to Methuselah (1921) that his idea of the “will” is a synthesis of Schopenhauer and Lamarck: Schopenhauer’s World as Will and Idea (1819) is “the metaphysical complement to Lamarck’s natural history.”41 It is not the same as Ibsen’s treatment of will, which emphasizes past events and their impact; for Shaw, this aligns Ibsen too much with Darwinism as it rules out the agency of the individual.42 Yet in one respect, that of sexual selection, there is some significant resonance with Darwin, as shown by Shaw’s depiction of women as the Life Force, a concept based on vitalism and similar to Bergson’s élan vital.43 One of the reasons Shaw liked the theory of sexual selection when he loathed everything else about Darwinian evolution was that sexual selection reinstated some kind of intentionality to human evolution after Origin of Species had expunged it. We choose our mates. That is some comfort in the teeth of natural selection’s randomness, blindness, and threat of regression. Sexual selection allowed for “some intelligence driving the motors of evolutionary development after all”44 and dovetailed well with Shaw’s Lamarckian belief in the role of the will in human evolution.

Apparently rejecting any form of determinism, Shaw placed the freedom of the human will at the core of his evolutionary vision.45 Yet biological determinism drives Man and Superman, and it is centered in women. Women’s “highest purpose and greatest function” is “to increase, multiply, and replenish the earth,” to choose the best mate for the perpetuation and improvement of the species, and “a man is nothing to them but an instrument of that purpose.”46 Women’s vitality is therefore “a blind fury of creation”47 and the social conventions of courtship and marriage a mere sham to hide the real locus of power in sexual selection:

TANNER: The will is yours then! The trap was laid from the beginning.

ANN [concentrating all her magic]: From the beginning—from our childhood—for both of us—by the Life Force.48

This determinism (“from the beginning”) is complicated by a moral element that Shaw, echoing Huxley, introduces to offset the troubling blindness of the relentless process of “construction and destruction” that constitutes evolution.49

Although both men and woman are the “helpless agents” of the “universal creative energy,” women have the burden of mate selection because of their childbearing capacity and thus their innate responsibility to ensure steady improvement of the species: life is a “continual effort not only to maintain itself, but to achieve higher and higher organization and completer self-consciousness.”50 Shaw had been developing this idea for some time; for example, in his play You Never Can Tell (1897), Valentine envisions nature as “suddenly lifting her great hand to take us . . . by the scruffs of our little necks, and use us, in spite of ourselves, for her own purposes, in her own way.”51 He explains that nature propels men and women together through some “chemical action, chemical affinity, chemical combination: the most irresistible of all natural forces” (or, as Tom Stoppard puts it in his play Arcadia [1993], “the attraction that Newton left out”).52 This mystery of attraction riveted Shaw’s attention. In Misalliance, a few years after Man and Superman, he is still musing theatrically on “the great question . . . the question which particular young man some young woman will mate with.”53

The famous Don Juan in Hell dream sequence (act 3) of Man and Superman elaborates Shaw’s theory of Creative Evolution and women’s roles within it. First, Shaw castigates Man’s destructiveness and stupidity. Then the discussion moves on to Woman, “the one supremely interesting subject.” Ann’s feminine power is on an evolutionary scale; Shaw’s stage directions seem to draw metaphorically on Haeckel’s recapitulation theory when he describes her as evoking “a mystic memory of the whole life of the race to its beginnings.”54 Don Juan explains:

Sexually, Woman is Nature’s contrivance for perpetuating its highest achievement. Sexually, Man is woman’s contrivance for fulfilling Nature’s behest in the most economical way. She knows by instinct that far back in the evolutional process she invented him, differentiated him, created him in order to produce something better than the single-sexed process can produce. . . . [And civilization is] an attempt on Man’s part to make himself something more than the mere instrument of Woman’s purpose.55

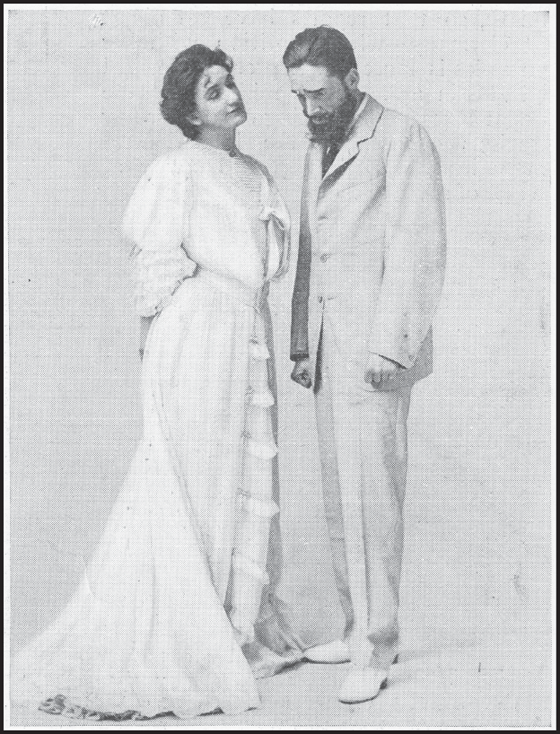

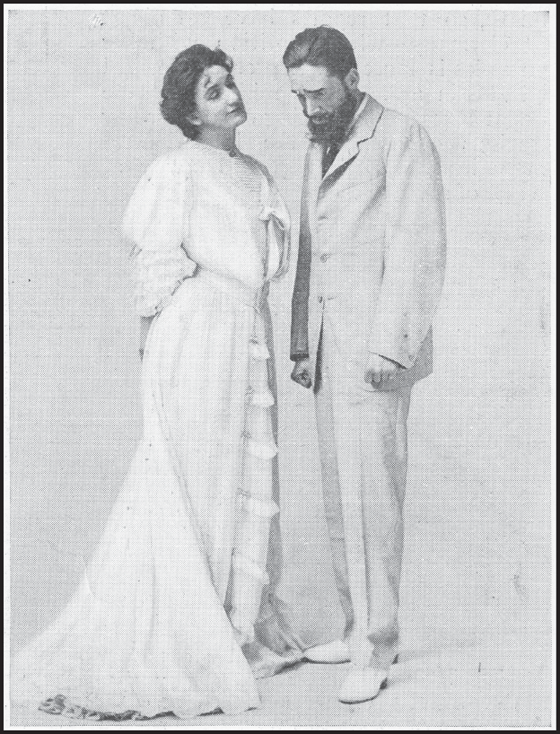

Shaw’s women cannot help themselves; yet their apparent taking of the initiative and overturning the shy, submissive maiden image—charmingly portrayed by Lillah McCarthy as Ann in the play’s first production (figure 1)—only replaces one rigid and misogynistic ideal of womanhood (the angel in the house) with another (the biologically driven woman ensnaring men in the service of the Life Force). The Philanderer’s Julie and Charteris are characterized in the stage directions as “huntress and her prey,” but Shaw’s women are just as trapped in their roles of predator as are the males in the “helpless” roles of prey.56

As Don Juan puts it, women are the channel for an intelligent force that helps Life “in its struggle upward,” when it would otherwise blindly waste and scatter itself.57 Just as we have evolved an eye for seeing the physical world, through this progressive process we will evolve “a mind’s eye” that will see the purpose of Life, and we will finally be enlightened enough to work for that purpose instead of “thwarting and baffling it” through our selfish, short-sighted aims.58 Don Juan sums up Creative Evolution: “Life is a force which has made innumerable experiments in organizing life itself,” whether the mammoth, man, mouse, megatherium, flies, fleas, and Church Fathers, all of which are “more or less successful attempts to build up that raw force into higher and higher individuals, the ideal individual being omnipotent, omniscient, infallible,” and essentially “a god.”59 Shaw becomes even more convinced of this years later in Back to Methuselah: evolution, he writes, builds “bodies and minds ever better and better fitted to carry out” the purpose of the Eternal Life; it is “the path to godhead. A man differs from a microbe only in being further on the path.”60

Figure 1 “Mr. Bernard Shaw burlesqued in his own play”: Lillah McCarthy and Harley Granville-Barker (made up to resemble Shaw) in Man and Superman at the Court Theatre, 1907. (© Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

He also asserts (as if the mere utterance will make it true) that “a reaction against Darwin set in at the beginning of the present century” that is leading “scientific opinion” to embrace Creative Evolution instead.61 Shaw’s quarrel with Darwinism seems straightforward: he cannot accept death, he dislikes gradualism, and he rejects the lack of agency—the aimless drifting, rather than purposeful direction, of natural selection. His views have much in common with those of Strindberg, who posits that world history proceeds not toward Spencerian homogeneity but with a mystical and “secretive . . . unconscious aspiration of mankind which is unaware of the goal but at the service of the conscious will.”62 Both needed to reinject agency into evolutionary theory, in contrast to Ibsen’s acceptance of its absence; intelligent design is implicit in their work. We are “tools in someone’s hand, someone whose intentions are incomprehensible to [us], but who looks after [our] best interests,” and Strindberg calls this being “the invisible legislator . . . the creator, the dissolver and preserver.”63

In Misalliance, death is pronounced as unnatural. “There wasn’t any death to start with,” explains Tarleton; then we appeared on earth and had to start dying off in order not to become overcrowded. “And so death was introduced by Natural Selection.” Even old age is the “invention” of natural selection, a “mask” of wrinkles and gray hair “to disgust young women with me, and give the lads a turn.”64 One of the points Shaw makes in Back to Methuselah, and which he had suggested earlier in other plays, is the idea of the invention of birth and death:

[FRANKLYN]: Adam and Eve were hung up between two frightful possibilities. One was the extinction of mankind by their accidental death. The other was the prospect of living for ever. They could bear neither. They decided that they would just take a short turn of a thousand years, and meanwhile hand on their work to a new pair. Consequently, they had to invent natural birth and natural death, which are, after all, only modes of perpetuating life without putting on any single creature the terrible burden of immortality.65

Shaw’s contrarianism can be understood in the context of other things he rejected, such as the idea of the bestiality of man, of which childbirth and meat eating are two examples he gives. His extreme rationalism led to a “fastidious mistrust” of “life’s irreducible physicalness, its messy, unpredictable, irrational uglinesses and beauties.”66 In the first part of Back to Methuselah, Cain declares a revolt against “these births that you [Adam] and mother are so proud of. They drag us down to the level of the beasts. If that is to be the last thing as it has been the first, let mankind perish.” Like Alfred Russel Wallace, whose article “Evolution and Character” (1908) suggested a progressive, improvement-centered, perfectible human evolution, Shaw wants mankind to be “something higher and nobler.”67

In addition to rejecting death, which “calls an end to progress, and mocks all human aspiration,” Shaw cannot accept Darwinian gradualism. He has no patience for the nineteenth-century insistence on evolution taking “millions of eons” of geological time and not proceeding “by leaps and bounds.”68 Shaw wrote Man and Superman during the period of (in Julian Huxley’s words) the “eclipse of Darwinism,” the phase when natural selection as the mechanism of evolution was challenged by other theories, such as Hugo de Vries’s mutationism (1901–1903; translated into English 1910), saltation, neo-Lamarckism, and even Haeckel’s monism.69 Books like Thomas H. Morgan’s Evolution and Adaptation (1903) were rejecting “both the selection mechanism and the idea that evolution could be driven by the demands of adaptation.”70 In other words, the question was still open (and would remain so until the New Synthesis came about) regarding what drives evolutionary change, and Shaw’s plays were unique interventions in that discourse.

But Shaw’s antipathy to Darwin is complicated by an embrace of Karl Marx and Continental philosophy, on the one hand, and a vehement antivivisectionismm, on the other, that attacks Darwin and all experimental scientists for chopping the tails off mice and the legs off dogs to prove natural selection. The Life Force has to experiment as it goes along, something Shaw kept depicting in later plays.71 It is “not so simple as you think. A high-potential current of it will turn a bit of dead tissue into a philosopher’s brain,” but the reverse can just as easily happen: “Will you believe me when I tell you that, even in man himself, the Life Force used to slip suddenly down from its human level to that of a fungus, so that men found their flesh no longer growing as flesh, but proliferating horribly in a lower form which was called cancer, until the lower form of life killed the higher, and both perished together miserably?”72

Shaw’s Lamarckian belief in the power of the will to effect physical and mental modifications is taken to outlandish extremes in Back to Methuselah, as the Ancients swap stories of extraordinary transformations they have willed into being, such as growing “ten arms and three heads” or becoming “fantastic monsters” with eight eyes and four heads.73 But these saltations are hardly genetic mutations. Shaw belongs more to the early evolutionists like Buffon than to contemporaries like de Vries. The end of Back to Methuselah signals not some mystical perfection of mankind as much as a return to Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s idealistic “coming race.” That is the fundamental quality of Shaw’s engagement with evolution: he refashions old ideas into the seemingly new package of Creative Evolution, often harking back to the pre-Darwinians while insisting on his own innovation.

It is easy with hindsight to dismiss Shaw’s Creative Evolution as wrongheaded and logically flawed. He gets the science wrong, and the eugenicist undertones can make his plays not only uncomfortable but also deeply problematic. But, as is so clear from his prefaces, he understands evolutionary theory perfectly well. For all the thousands of words he expends in trying to distinguish his theory from Darwin’s, it seems to boil down to a single concept—agency. Are we simply to sit by and contemplate a universe that is “cruel and terrible and wantonly evil” as well as “oppressively astronomical and endless and inconceivable and impossible?” This question still plagues him in late plays like Too True to Be Good (1932).74 If so, we should “go stark raving mad” and stick straws in our hair. No, we must do something, must intervene; there must be a purpose, and humans must be its agents; we can improve and perfect and make progress with the raw materials around us. The things that are of no use must be “scrapped” as he puts it in play after play (Major Barbara, Back to Methuselah, Heartbreak House), either by the random forces of nature or by human purpose. Between Man and Superman and Back to Methuselah, this optimistic vision does briefly dim (World War I separates the two), and the latter is “full of ominous warnings that the Life Force may find it necessary to discontinue the human race”75—to scrap it, as Undershaft would say. Heartbreak House (1919) illustrates this in graphic fashion through exploding several of the characters. Extinction is all right if something is obsolete or no longer useful because it is in the service of overall improvement, which mandates the permanent killing off of ineffective organisms and (most importantly for Shaw) outlooks and ways of life.

Shaw’s interest in evolution has to be seen in relation to other factors besides theories of evolution. It is tied to a wider interest in cultural agency: Shaw the playwright wants to reinvest the theatre with the powerful cultural role it once enjoyed, and in dozens of articles and prefaces throughout the 1890s and early 1900s, he inveighs against the ineffective contemporary theatre, its managers, the censorship, and the playwrights enslaved by the box office. In addition, he is writing at a time when, as Peter J. Bowler notes, evolution itself is being treated differently, assimilated as “part of a more general transformation of biology . . . related to developments in genetics, ecology,” and ethology.76 Given the ongoing “debates over the public and political role of science” (and, one might add, of theatre), it is natural that they should converge in the work of one so given to “polemic, influence, argument, debate.”77 Back to Methuselah is one of his most important contributions to this debate, as he attempts to stage evolution as well as stretch the limits of theatre without relinquishing box office concerns. In other words, he wants to have it all: Back to Methuselah (subtitled A Biological Pentateuch) opens in the Garden of Eden, ends thousands of years in the future, and cumulatively depicts the Life Force that directs evolution toward ultimate perfection by trial and error. Let us look in more detail at this modern megatherium of a drama.78

In the introduction, I quoted Henry Arthur Jones’s observation about the seemingly impossible challenge for the theatre in engaging evolution: how to represent in a few hours a process that takes millions of years. Shaw cleverly deals with this in Back to Methuselah by having variations on his characters in the five plays that make up the cycle, usually played by the same actors. So, for example, the Accountant General looks rather like Conrad Barnabas, and “even the two politicians make a reappearance as a composite in the President Burge-Lubin.”79 Then, in part 5, “As Far as Thought Can Reach,” he calls for a character whose face is so ancient that it seems as if “Time had worked over every inch of it incessantly through whole geologic periods.”80 These human variations and the immense amount of time covered in the course of the cycle combine with the tricks of stage make-up to convey the impression of evolution happening before our eyes. Although Shaw saw human beings as the highest achievement of nature, he was profoundly dissatisfied with what collectively had been achieved so far—due, he believed, to too short a life span to be able to accomplish much.81 Thus, Back to Methuselah offers a solution to the earlier despair of Man and Superman at how “wretched” our brains are, considering we are “the highest miracle of organization yet attained by life, the most intensely alive thing that exists, the most conscious of all the organisms.”82

Darwin wrote in his Autobiography that “man in the distant future will be a far more perfect creature than he now is,” and Shaw also believed this; but would man necessarily be “more perfect” in the way Shaw depicts? Is it not a paradox that the ultimate result of this striving toward perfection is shown to be evaporation, vanishing, the flesh becoming spirit? Lilith’s final lines before she vanishes at the end of Back to Methuselah are full of monistic rejections of all matter and a yearning instead for a state in which “the whirlpool” becomes “all life and no matter.”83 As at the end of Man and Superman, all that remains is “talk,” except here it is literally just the human voice, all that materially remains of the now perfectly evolved mind. The only way to achieve this pinnacle is through willing a longer life, an idea Shaw was still hammering at as late as Geneva (1938), staging the notion that we must lengthen the human life span to gain enough wisdom to govern ourselves.

The long-lived people in Back to Methuselah do eventually die, not of natural causes but through accidents or through “discouragement,” a fatal attribute. Apparently “discouragement” came to Shaw through Strindberg, who was convinced that “every meeting of individuals implied a psychic conflict to establish the mastery. This soul-conflict was the spiritual aspect, he thought, of the physical struggle for survival which Darwin had described in The Descent of Man.”84 Perhaps Francis Galton’s Inquiries into Human Faculty (1883) was another source; Galton suggests that such discouragement affects “savages” when they first come into contact with white civilization—for example, Native Americans’ “collapse of morale” and “the actual extinction of some races, such as the Caribs and Tasmanians.” Louis Crompton notes Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s The Coming Race as a further influence.85

Shaw proposed protracted longevity as a way of offsetting the hugely frustrating fact that at present our “first hundred years” of life are a state of “confusion and immaturity and primitive animalism” because we are dominated by sex.86 Shaw is obsessed with sex but somehow finds it distasteful; it is as if his view of procreation can be found in Eve’s revolted response to the Serpent’s whispered explanations. Back to Methuselah shows childbirth now replaced by children hatching from eggs: the audience witnesses a full-grown teenage girl emerging from a giant egg center stage. This solves one of the problems of human evolution: that we are altricial—immature at birth, requiring a long period of dependence. In his preface to the play, Shaw pins great hopes on embryologists’ “astonishing” discovery of recapitulation to help humans learn how to speed up “into months a process which was once so long and tedious that the mere contemplation of it is unendurable by men whose span of life is three-score-and-ten.” He claims there are already examples of this “packing up of centuries into seconds” in the form of child prodigies.87

In fact, in Shaw’s plays “children rarely make an appearance unless they are of a marriageable age.”88 Thus, paradoxically, there is a gap between woman’s compulsion to reproduce and the natural result of this drive; we are shown only the former. Perhaps this is mere theatrical expedient: “Although it would seem logical to conclude that women live for the sake of the children they may have, this desire is not so easily conveyed in drama.”89 This relates to Darwin’s observation in Descent of Man that maternal love is paradoxically difficult to articulate through facial expression. But this explanation ignores Shaw’s revolutionary feminism, his championing of women’s liberation from the burdens of motherhood, his attack on the institution of marriage for its constraints on women. In his preface to Getting Married, Shaw says that the one thing all women are in rebellion against is that having a child necessarily entails being “the servant of a man.”90 In keeping with the developing discourse on women’s roles, particularly motherhood and marriage, Back to Methuselah enacts the conflict between the reproductive burden on women and their right to independence.

Not surprisingly, there has been much debate over Shaw’s depiction of women’s roles within his evolutionary vision. A substantial body of critics maintains that Shaw limits women even while he seems to be arguing for their importance and that he only pays lip service to women as biological agents of evolution, as he “ultimately allows the male intellect to dominate in his plays. . . . Both the new woman and the man of genius are dedicated to the male role of contemplation. . . . Man’s role as the intellectual agent of evolution is, accordingly, the most important one in his drama.”91 Jill Davis argues that many of Shaw’s plays are “profoundly misogynistic,” especially Getting Married and Man and Superman, in which he attempts to “reorganise feminist arguments to masculinist ends . . . [as a] conscious response to feminist threats to male sexuality.”92 Although it may well have been problematic and limited in its suggestion that women’s duty is to ensnare a mate to perpetuate (and, crucially, improve) the species, as Sos Eltis points out Man and Superman was “one of the first plays where a respectable young woman’s sexual drive was both the crux of the plot and a central topic of debate.”93

It is perhaps a paradox that “a man of Shaw’s profound understanding and personal shrewdness gave, for the last thirty-five years of his life, the wrong answers to almost all the questions that have perplexed our age.”94 Note again this idea of wrong-headedness and contrarianism. J. D. Bernal calls him “a violent and reckless supporter of scientific lost causes, like Lamarckian Evolution” and opponent of theories and practices that “in the course of years have proved their truth and usefulness, like the bacterial theory of disease.”95 Theatrically as well as scientifically, Shaw has received criticism. Wilder commented in 1951 that Shaw was a particularly “tiresome” variant of the “bellicose” Irish geniuses who “only discover what they think through the act of repudiating what someone else has thought. This makes for wit and energy as certainly as it makes for overstatement and personal ostentation.”96 This is significant in light of Wilder’s own attempt to stage evolution, as explored in chapter 7.

What should be the final verdict, then, on Shaw’s engagement with evolution? The fact that we are still so divided over him—feminist or misogynist? theatrically innovative or hopelessly unplayable? backward looking or visionary?—indicates his ongoing vitality and relevance. And, for all his contrarianism, Shaw’s evolutionary vision was capacious enough to include a positive nod toward Darwinism. In Too True to Be Good (1932), the Elder recalls how at difficult times in his life he sought “consolation and reassurance in our natural history museums, where I could forget all common cares in wondering at the diversity of forms and colors in the birds and fishes and animals, all produced without the agency of any designer by the operation of Natural Selection,” rather than “some freakish demon artist, some Zeus-Mephistopheles with paintbox and plasticine.”97 This makes it all the more essential to understand Shaw’s plays in their context, to see how he fits into an extant discourse on evolution that may have been shown to be “wrong-headed” much later but nonetheless had a significant following at the time and that poses fundamental questions that are still relevant. He also has his comic side, and this must be taken into consideration; one can take Shaw too seriously and at face value, forgetting that he is a playwright who can write a play that features a microbe on stage (“In shape and size it resembles a human being,” he tells us, presumably with a straight face, in the stage directions to Too True to Be Good, “but in substance it seems to be made of a luminous jelly with a visible skeleton of short black rods”).98

Genetics Enters the Scene

That Shavian mixture of paradox and comedy with serious intellectual and moral questions characterizes so many Edwardian playwrights, particularly in their engagements with evolutionary issues. The Italian director Luca Ronconi notes a peculiarly British ability to write plays with “an ironical, not at all pedantic tone,” dealing with subjects “in a light way, but without diminishing the seriousness of the topic.”99 In this vein, Shaw’s contemporary James M. Barrie, best known for Peter Pan, uses the language of evolution and enacts motifs such as adaptation and the struggle for existence in his hugely successful play The Admirable Crichton (1902).100 A now-forgotten contemporary of Shaw and Barrie was Hubert Henry Davies, three of whose plays reflect contemporary developments in genetics and evolutionary theory, sciences that provided him with rich dramatic metaphors. Of these, Mrs. Gorringe’s Necklace (1903 premiere) is the least innovative; it contains references to heredity and specifically to degeneration and, like The Admirable Crichton, suggests the impossibility of permanent change. Davies’s comedy (masking a deep tragedy) argues that the “curse of degeneracy” can never be shaken off and will “taint” an addict’s children.101 Mrs. Gorringe’s Necklace thus sits firmly within a nineteenth-century naturalist tradition. Although some hope is briefly offered that the protagonist, David, can “triumph” over his problem, he despairs that “the curse is always there in my mind and heart. I’m tainted—.” He writes a farewell letter to his wife and then takes a revolver out into the garden and kills himself.102

Nothing could be further from a play written a few years earlier addressing exactly the same theme, Man and His Makers (1899) by Wilson Barrett and Louis N. Parker, which presents degeneracy as not hereditary but all in the mind.103 No one is fated or doomed by his or her parents’ indiscretions. The hero, John Radleigh, is informed by his would-be father-in-law that he comes from a long line of drunkards and opium and morphine addicts. As soon as he hears of it, John promptly begins to succumb to this family weakness. At his nadir, he is penniless in St. James’s Park and surrounded by society’s other refuse, in a scene of deep pathos that shows a poor woman in such despair that she is taking her baby to the river to drown it, only to discover that it has already died in her arms. John is rescued by his true love, Sylvia, who has been forbidden by her father to marry him, and the play ends ten years later with him with a happy, healthy family and a prosperous job. At the end of act 2, Radleigh proclaims his optimistic stance in the face of all the despair in society, even in the face of science: he alludes to entropy and heat death when he says that men “faint at fresh air; and their only comfort in the sun is that it’s gradually going out,” which is where he was mentally when he took opium, until he was rescued. Now, “give me fresh air, I say, and Long live the Sun!”104—an obvious echo (and transformation) of Oswald’s dying invocation of the sun in Ibsen’s Ghosts. But whereas Oswald has no power against disease, the notion of “flying in the face of science” lies at the core of Man and His Makers.105

These two directly opposed plays by Davies and by Barrett and Parker show how theatre intervened in an ongoing discourse spread across all cultural forms about the nature of so-called degeneracy and its impact on human evolution. Already by 1899, a certain fatigue had set in, though, and reviewers of Man and His Makers found the repeated references to the theory of heredity tedious, even though the play’s aims were deemed “admirable.”106 One reviewer simply could not fathom what species of play this might be: “A work of this class hardly comes within the ordinary dramatic categories.”107 The most remarkable review, for its scientific specificity, came from the Pall Mall Gazette. The reviewer discusses specific scientists in relation to the play, saying it is hard to tell how far the playwrights are “fellow champions with the ‘progressive heredity’ and ‘the heredity of acquired characters’ of Mr. Herbert Spencer, or how far they are attacking the theories of Weissman [sic], who would explain the whole of transformism by the ‘all-sufficiency of selection.’ Probably, like wise men, they thought of neither the one nor the other . . . [but of] whether [the play] were dramatically sound rather than scientifically correct.” Quite apart from the feeble punning on “wise men,” the critic sets dramatic “soundness” and scientific accuracy in opposition, as if a play cannot be both theatrically viable and scientifically truthful, a debate that is still with us today. The reviewer also notes that the theme of heredity had most recently been dramatized by Brieux in L’Evasion at the Comédie Française with the aim of showing that, “however strong heredity, there is always the will to combat it.”108 Finally, the reviewer says that John should have done what any “sensible” man would do on hearing the news that he has a heredity tendency to drink: seek a scientific opinion.

As these contemporaneous plays show, the workings of heredity were not yet clear in the public discourse—what exactly could be passed on, what could be combated with will and determination as well as with medical intervention, and how heredity actually worked. Even in the late 1920s, Max Beerbohm criticized Barrie’s play Old Friends for having an Ibsenic theory of heredity whereby the daughter of an alcoholic will herself become a drunkard. “The child of a drunkard, though its health is in many ways affected by its father’s habit, will not, when it grows up, have any special cravings for alcohol,” unless it had been brought up to share the father’s habit, making it more likely to acquire that condition.109 He wonders how Barrie can be so ignorant of these basic facts.

Heredity also runs through the play for which Davies was best known, The Mollusc (1903).110 Though now obscure, as late as 1928 Play Pictorial was recalling how The Mollusc had been “hailed as a triumph of craftsmanship” at its premiere and how “its fame has endured till this day.”111 The leading male role of Tom Mowbray was played by Charles Wyndham, who by then was seventy years old, playing a forty-five-year-old who falls in love with a young woman in her twenties—yet he was praised for his energy and vitality. The “mollusc” of the play’s title is his sister, Mrs. Baxter. As Tom explains to her exasperated husband, she is a specimen of “Mollusca, subdivision of the animal kingdom” (“I know that,” Mr. Baxter says testily). Davies injects some zoology into the play while pushing the science toward metaphor: “I don’t know if the Germans have remarked that mammalia display characteristics commonly assigned to mollusca. I suppose the scientific explanation is that a mollusc once married a mammal and their descendants are the human mollusc.”112 Tom explains that these hybrids, these human molluscs, cling to the rocks while the tide flows over their heads; they have an instinct for molluscry, and it spreads like an infection throughout the household. It stems from women (“mother was quite a famous mollusc”), but it is not the same thing as laziness; it is a kind of resistance: “The lazy flow with the tide. The mollusc uses forces to resist pressure. It’s amazing. . . . [It has an] instinct not to advance.” There are some people who find routine boring, who “suppose the secret of existence to be mutability, the fact of never knowing, from day to day, what strange adventure shall befall,” but Mrs. Baxter every day “looks forward to tomorrow as a replica of to-day.”113 Mrs. Baxter, a “perfectly healthy woman,”114 is like a mollusc because she clings to her rock while life goes on around her, and she resists pressure, growing a metaphorical carapace. And just as molluscs have long been associated with luxury for humans—pearls, sea silk, Tyrian purple dye—Mrs. Baxter luxuriates in being waited on and living in extreme comfort.

What is interesting is not so much the obvious metaphor but how the biological language enters into the dialogue and how it refers to evolutionary processes—perhaps even counter-evolutionary, if one considers the idea put forth by Tom that molluscs have the ability to resist change and adaptation to their environments and to ignore the environmental pressures on them. This also shows a playwright making assumptions about cultural absorption: throwing certain evolutionary ideas (adaptation and progressiveness) into his plays and assuming that the audience has some prior exposure to a discourse on these themes and issues.

In fact, the play was well received and praised for its successful integration of science, done with a light touch. Percival P. Howe wrote that “nothing could be more delicate than the art with which we are told about molluscs.”115 The Athenaeum called it “the lightest of light comedies,” portraying “that type of woman who makes everybody around her wait hand and foot upon her, and takes advantage of other folk’s good nature to spare herself the least exertion. . . . An indolent, selfish woman who avoids any kind of locomotion.”116 Walpole repeatedly praises the whole of The Mollusc, while other Davies plays are only partially successful in his view: “Mrs. Baxter goes gloriously on, far into time, triumphantly conscious that she will get her way so long as there is a man in the world, a way that no votes for women can affect so long as human nature remains unchanged.”117 Beerbohm called it “exquisite” and “truly delightful” and explained that “in the brute creation a mollusc is a shellfish that firmly adheres to a rock, doing nothing but adhere, while the tide ebbs and flows above it. Thus, in the human race, a mollusc is a person who will not lift a little finger to perform any duty” that someone else could do instead.118

But Davies’s use of this metaphor is, in fact, misleading; in reality, even though they seem not to be doing anything, molluscs are amazing engines of adaptation. Whereas the play suggests that Mrs. Baxter is forcing everyone to adapt around her while she remains static and unchanged, this is the reverse of what happens in nature. Drawing an analogy with performance, Rebecca Stott notes that marine invertebrates played a central role in evolutionary theory because they were “the key to understanding the complicated biological processes of all ‘higher’ animals.”119 She notes the popularity of the aquarium from the mid-nineteenth century: the first Aquatic Vivarium was set up in the Zoological Gardens in 1853, enabled by Philip Gosse’s discovery of how to make artificial seawater that would be viable for marine creatures. The newly opened aquarium became “one of the spectacles of London.” These tanks were “theatres of glass in which sea creatures performed epic natural dramas,” and soon “aquarium mania began to sweep the country” and people flocked to see such “entertaining and philosophical” creatures.120 This is precisely the assumption behind The Mollusc. The audience—newly trained in encountering natural history through not only such “theatres of glass” but also zoos, geological displays, and museums—is able to detect the underlying drama in a seemingly static show.

Huxley’s strenuous work in popularizing Darwin’s ideas, including the groundbreaking study of barnacles, might also have played a role. Again in the theatrical vein, Stott notes that Huxley turned the barnacle into something rather comical, “a theatrical zoological sideshow,” by his description of it in Westminster Review, in which he drew an analogy with Mr. Punch and his hump: “He anthropomorphized the barnacle as a man settling down, gluing himself to a rock.”121 This is exactly how Davies portrays Mrs. Baxter, though turning the condition of being a mollusc into a specifically female malady.122 This transformation was not lost on Beerbohm. In his response to the play, Beerbohm tries to get past the clichés by drawing on known facts about molluscs. He notes that although the mollusc has been feminized, in reality “the human mollusc is often masculine.”123 But Davies also is on top of his facts; in the play, Tom admits to being a mollusc himself, the difference being that he fights this condition rather than succumbing to it.

Continuing to mine evolution-related topics for theatrical metaphors, Davies in his comedy Doormats (1912) reflects the buzz about genetics that William Bateson helped to generate.124 Davies’s highly topical comedy plays with the idea of “dominant” and “recessive” types of people. Working with his pea plants, Gregor Mendel posited that there were dominant and recessive elements; recessives are expressed only when the same element is passed on by both parents, while dominant ones can be expressed even if only one element is present.125 The play borrows terms from this new science—terms that the playwright evidently felt confident audiences would recognize and understand—and adapts them to suit his purposes, as a metaphor for the two main types of people in the world, masters (boots) and slaves (doormats), represented in the play by Noel, a doormat-like painter who is married to Leila, a boot-like young woman who is self-absorbed, restless, and fickle. By the time Davies has woven this metaphor, the terms have been so modified that they retain almost nothing of their original scientific meaning, for dominant and recessive are not value-laden terms (i.e., strong and weak) in the way that they become in the play.

Indeed, Aunt Josephine, a wise middle-aged woman who is the play’s voice of reason, springs on everyone the surprise revelation that she also is a doormat, and the problem is that doormats “wilfully lay ourselves down to be trampled upon. We love being trampled upon. It thrills us to give and it bores us to take. It’s of no use knowing—with one’s brain—how to take if one hasn’t got their instinct—.”126 This is a surprise because outwardly she betrays no sign of that allegedly negative trait. She has evidently been able successfully to adapt to her condition. It is the same twist that we saw in The Mollusc when the highly active and energetic Tom had confessed to being a mollusc himself. Through these characters, Davies makes the point that what might seem to be non-adaptive can in fact be turned to advantage.

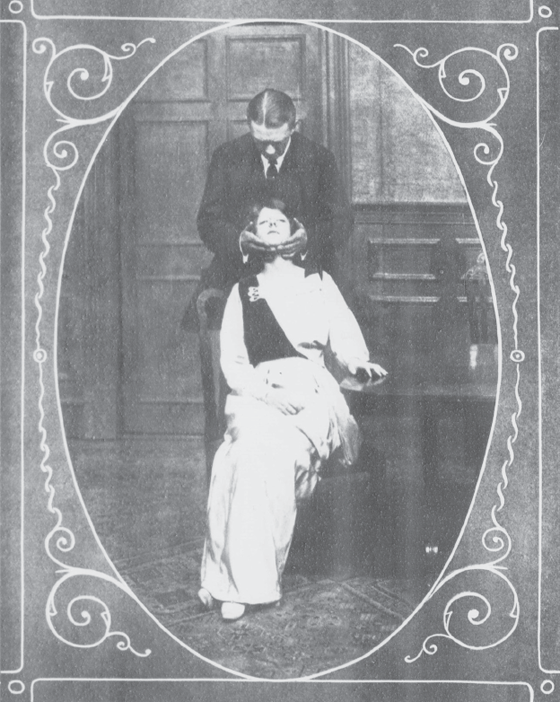

Although Davies does not repeat the gendering that occurs in The Mollusc, since Doormats shows that either gender can be dominant or recessive, he does assume gender essentialism. Josephine says further in the play that some people give and some take, and one cannot change that: “You can’t not be whichever kind you are, any more than you can change your sex.”127 The events of the play do question this determinism as Leila, who has left Noel, in the end wants him to take her back.128 But the final moments of the play show their reconciliation in a highly ambiguous tableau: Noel stands behind a seated Leila, his hands cupping her chin, pulling her head back as the stage directions indicate, while she stares unsmilingly out at the audience, looking like a trapped animal (figure 2). The picture’s caption paraphrases the final lines of the play and summarizes its theme: “Noel and Leila find that the ‘boots’ need their ‘doormats’ just as much as the ‘doormats’ need their ‘boots.’” This undermines both the suggestion of the ideal pairing of these two opposites and the genetic metaphor at the center of the play.

It is worth looking more closely at how Mendelian dominants and recessives work in this play. Aunt Josephine spells it out (as Tom does in The Mollusc):

Just as every one is either a man or a woman—not in the same degree of course—but there are men and women—(illustrating with her hands) at either end, as it were, of a long piece of string; very mannish men at one end and very womanish women at the other. Then—as you go along—men with gentler, what we call feminine qualities—and women with masculine qualities—some with more and some with less—right along—till you come to a lot of funny little people in the middle that it’s hard to tell what they are. Just so, it seems to me, is every one a more or less pronounced doormat or boot.129

The metaphor is not all that is of interest here: note the ingenious syntactical construction by which the gender essentialism that has just been established is undermined a few lines further.

The play’s use of genetics did not pass unnoticed. According to Howe, “If Professor Bateson of Cambridge University had written [the play], no doubt he would have given it a more scientific name. But Mr. Davies’ art prefers the more homely analogy of the doormat and the boot.” And the play’s construction is perfect because the older couple (Josephine and Rufus) mirrors the younger (Noel and Leila): “dominant and recessive . . . only the other way round.”130

Figure 2 “The Reconciliation” between Leila (Marie Löhr) and Noel (Gerald du Maurier), capturing the final moments of Doormats by Hubert Henry Davies, from a twenty-two-page feature on the production in Playgoer and Society Illustrated (December 1912).

The reference to Bateson is significant. In 1902, Bateson published the first English translation of Mendel’s paper. Bateson also coined the term genetics, which he first used publicly in a lecture in London in 1906. The leading British geneticist, he helped to found the field, was appointed to the new chair in genetics at Cambridge in 1908, and established the Journal of Genetics in 1910; he then became director of the John Innes Institute from 1910 until his death in 1926.131 As a hard-line Mendelian, he was an anti-Lamarckian who did not believe that environment could influence heredity. In addition, Bateson believed in saltation rather than gradualism: he claimed that “discontinuous variations (saltations) were the real cause of evolution,” and this was even before the rediscovery of Mendel’s laws.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, as Bateson’s Cambridge group helped establish the field of genetics, a deeply divisive and highly public debate developed between Bateson and his followers (the hereditarians, or the Mendelians) and the followers of Karl Pearson (the biometricians). As Daniel J. Kevles points out, “The biometrical–Mendelian debate . . . reached a level of vitriolic intensity” in Britain that was never matched in the United States, Bateson labeling zoologists “nincompoops” full of “ignorance and bigotry” when a paper by one of his collaborators was rejected for publication.132 By contrast, in America, a vigorous and high-quality level of genetics research obtained, comparatively unencumbered by such bitter disputes. In both cases, though, “the pursuit of genetics was also . . . affected by social forces, notably the eugenics movement.”133 In 1913, Pearson, Edward Nettleship, and Charles H. Usher objected to the general trend to apply Mendelism “wholly prematurely to anthropological and social problems in order to deduce rules as to disease and pathological states which have serious social bearing.”134 In a sense, Doormats does just this, although—unusually for a piece so clearly of its time in its direct engagement with genetics—it does not play the eugenics card.

It is unlikely that audiences knew all of this or that Davies himself did, but it is safe to assume that genetics was “in the air” in 1912, due to the very public, “vitriolic” debate of Mendelians versus biometricians. Added to this, in 1910, the notion of the inheritance of feeblemindedness was hotly debated as Charles B. Davenport claimed that it was “a simple Mendelian recessive.”135 Davies drops such buzzwords into his play. The central, burning question for many was fitness—physiological, moral, and mental. One of the fascinating side elements of Doormats in this context is its use of an artist as the central figure; as Bateson noted, artists served as soft targets for the eugenicists because of their eccentricity and apparent unproductivity: “In the eugenic paradise I hope and believe there will be room for the man who works by fits and starts [such as] Bohemians, artists, musicians, authors, discoverers and inventors. . . . I imagine that by the exercise of continuous eugenic caution the world might have lost Beethoven and Keats, perhaps even Francis Bacon.”136

Davies’s work was, for one reviewer, marred by his “hesitation between comedy and tragedy.”137 The same “lightness” of treatment that earned him praise became in the end his undoing in terms of durability, for even his engagement with science remained for some merely a dabbling: “Davies’s mind was essentially conventional, and never more so than when he was taking what he believed to be an unconventional point of view.”138 The author of this appreciation of Davies’s work concludes that he is “almost equal to Hankin.” The writer is referring to their dramaturgy—tone, form, structure, dialogue—but it is also notable that they share an interest in using biological motifs. Where Davies eschews eugenics, though, Hankin addresses it head on.

Although he is seldom revived and has only a single, slim biography now over three decades old and only a clutch of scholarly articles, Hankin must figure prominently in any consideration of the Edwardian theatre’s engagement with evolution. He is closely allied in spirit and dramaturgy to key playwrights of his time, such as Shaw, Davies, Harley Granville-Barker, John Galsworthy, Elizabeth Baker (discussed further in this chapter), Barrie, and Brieux, whom he greatly admired and one of whose works he translated. Hankin incorporated into his works “what was perhaps the most unpopular disposition of his time: an open regard to eugenics and social Darwinism, along with a wry awareness of the impossibility of any tranquil panegyric for society.”139 The Return of the Prodigal, his second full-length play, shows Hankin hitting his dramatic stride in “a curious hybrid of comedy of manners and Darwinian philosophy,” a mode similar to that of Davies.140 With its emphasis on the strong versus the weak—and its direct allusion to “survival of the fittest”—the play might seem more Spencerian than Darwinian. But, by not ending the play with marriage between Eustace and Stella, Hankin rejects the Victorian ideal of the “ennobling power of woman and marriage” that is implicit in Spencer’s philosophy, just as Shaw does in so many of his plays.141 Hankin casts life as a struggle between predators and their prey. Eustace, sounding like a mixture of Darwin and Zola, does not believe we have free will; survival is determined by one’s environment, heredity, and chance. This explicit espousal of natural selection and adaptation was “rare in English drama and unprecedented in a comedy” in the first decade of the twentieth century.142

Deeper consideration of Hankin will be given in the following chapter (on reproductive issues) with regard to his play The Last of the De Mullins, but it is worth noting here that his work also encompassed other evolutionary concepts as well, such as extinction, competition, and altruism. In his play The Charity That Began at Home (1906), the theme of survival of the fittest is more “muted,” foregrounding instead a larger philosophical question about human nature: Are we really meant to help one another, or does that just lead to more misery and suffering?143 Verreker declares that charity is interfering: “People who try to improve the world have rather an uncomfortable time.” Extinction features in The Last of the De Mullins (published 1909; produced by the Stage Society in its 1908/1909 season); the child that resulted from Janet’s illicit affair is the “last” of Janet’s family line, which she dismisses as “your ridiculous De Mullins.” As we have seen, familial extinction is a preoccupation of other plays of the period, such as Henry James’s Guy Domville and de Curel’s Les Fossiles, even though the seemingly tragic status of being the last of the Domvilles and De Mullins is questionable given the existence of illegitimate offspring.

The theatrical landscape in this period is thus saturated with evolutionary issues and ideas, but it is distinct from its Victorian predecessors. The emphasis on exterior landscape shifts to the internal situation—not only the domestic interior but also the psychological one and, beyond that, the invisible physiological landscape inside each individual that was beginning to be probed and revealed by science. Most prominently, the treatment of heredity is changing: the preoccupation with the inheritance of acquired characters, the pessimistic rendering of the “sins of the fathers” being passed on to the sons, and the generally passive, deterministic depiction of the workings of heredity give way to a sense of identity and genetics as malleable and mutable rather than fixed. When Virginia Woolf famously asserted that human character changed in December 1910, chances are that she was not thinking of the theatre; but considering this statement in light of broader cultural changes at this time gives it new meaning. By this time, genetics has become a well-established field and is rapidly changing the way scientists understand evolutionary mechanisms. Playwrights embrace the possibilities opened up by this new sense of the flexibility of character. It is also the moment when both the suffrage campaign and the eugenics movement gain a tremendous amount of public attention. Theatre becomes a site where new ideas converge, and the spectrum of questions it poses is all-encompassing: What is the nature of identity? Can we liberate ourselves from our culturally conditioned assumptions (suffrage)? Or is our biology our destiny? What happens if we manipulate this biology? What can we do to correct nature’s mistakes (eugenics)?

Reviving Freakery

An extraordinary play was produced in 1918 that broached this last question directly to the audience: Arthur Wing Pinero’s The Freaks. The play speaks to a continued public interest in freakery, but registers a notable change in the nature of that interest: the Victorian fascination with human anomalies as a link to our evolutionary origins is replaced by a curiosity about otherness and disability that was concomitant with the returning war wounded. The Freaks is itself something of an anomaly and has received scant attention since its premiere in 1918.144 Like Edward F. Benson’s The Freaks of Mayfair (1916), the title foregrounds “freaks” and makes the same argument—that the real freaks are the aristocrats—but goes one step further by bringing actual freaks together with these upper-class specimens.145 As with much more recent plays like Suzan-Lori Parks’s Venus, Mary Vingoe’s Living Curiosities, and Bernard Pomerance’s Elephant Man, Freaks re-creates the Victorian freak show with a view to showing the people beneath the deformities and arousing sympathy for their plight, showing the consequences of their exploitation both by their handlers and by the audiences who paid to see them—including, of course, those watching the play itself.

The list of characters divides the persons of the play between “ordinary mortals” and “extraordinary mortals,” the latter all “late of Segantini’s World-Renowned Mammoth International Hippodrome and Museum of Living Marvels.” The “extraordinary mortals” have been let go by Segantini and are sympathetically described by the well-to-do Mrs. Herrick, who takes them under her wing, as “poor souls . . . Freaks . . . human oddities, doomed to exhibit themselves as a side-show of a circus, or in a booth at a fair.”146 Pinero tests our prejudices by not showing us the freaks themselves until after the ordinary mortals have described them. This forces each audience member to fall back on cultural clichés and stereotypes of freakery that the play will then dismantle.

Pinero’s depiction of freakery draws on authentic, real-life examples. Tilney, Pinero’s “Skeleton Man,” is most likely an echo of Mr. Tipney, the most famous skeleton man of the Victorian period, and the rest of his troupe of human anomalies is also fairly standard: a giant (9 feet tall), a female contortionist, and two “little people.” The group was depicted arrestingly on a drop curtain by the well-known artist Claude Shepperson, a frequent contributor to Punch, and this was reproduced as a two-page spread in Tatler: “A special feature of the production was a ‘Wonderful Drop-Scene of the Freaks,’ used instead of a curtain between the acts, from a painting by Claude Shepperson portraying the troupe entertaining an audience that was made to appear more freakish than the performers at whom they were gawking” (figure 3).147

The production featured prominently in Tatler, which published not only Shepperson’s painting but various photographs of the actors over several issues. This suggests that the production was very much in the public eye and that its premature closure due to air raids was the reason for its demise as a play, rather than theatrical inviability. Ironically, then, The Freaks was a victim of the very circumstances to which it alluded: “This satiric lesson of man’s inhumanity to man suffered the effects of two air-raids in its opening days and, despite full houses and an enthusiastic welcome, closed” after a run of fifty-one performances.148

Figure 3 “The wonderful drop-scene of The Freaks”: Claude Shepperson’s drop-curtain for The Freaks, a play by Arthur Wing Pinero. The curtain was displayed across the stage between the acts and was reproduced in Tatler (February 1918), along with photographs of the leading actors. (© Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

It would have been challenging to stage a play that required half the cast to be freaks. How would they be played convincingly, if not by actual freak performers? Pinero alludes privately to the “difficulties of presentation” and theme that might prevent the play being produced in America.149 His stage directions certainly seem to call for complete realism. Tilney is “emaciated,” with “a pale face and sunken cheeks.”150 Eddowes is a giant “between eight and nine feet high,” while the two midgets have “lined, wizened features, a tottery gait, and heads which, being too heavy for their necks, have a tendency to lop on one side.”151 And there is no possibility that these figures are just glimpsed briefly; Tilney introduces each one in turn, and he presents them as relics of both an evolutionary past and a theatrical one, expanding in one stage picture the spectrum of the human. Indeed, he refers to them all as “by-products of the animal kingdom.”152 Sheila, the “normal” girl who falls in love with Tilney, probes him on his origins as if getting at a much bigger ontological issue. “Who are you?” she asks. “What have you sprung from, Mr. Tilney; where were you born; how did you come to be mixed up with this curious crowd?”153

The subtitle of the play (An Idyll of Suburbia) directs the focus on the nonfreaks (and most of the theatre audience) who inhabit suburban London and gives the sense that this space represents the status quo that is only briefly jeopardized. In fact, the “normal” and the freak groups turn out to be related: Segantini was Sheila’s uncle. The centerpiece of the play is Tilney’s “who is a freak” speech, syntactically and thematically echoing Shylock’s “what is a Jew” soliloquy in The Merchant of Venice:

TILNEY: Who is a freak and who is normal in this world? Who shall decide? . . . Are there no Freaks in your list of acquaintances? Are all the women you lip, and all the men you rub palms with, beautiful specimens of the normal—the Christian—type? And yet you sneer at my poor grotesque companions, who, in spite of infirmities of body and temper, have more true love in their hearts, treat ’em kindly, than seventy-five per cent. of the well-formed and the well-endowed. [Grinding his teeth.] Freaks, are they! . . . Looking into the faces in front of me at our shows, my hardest task has been to refrain from crying out that we ought to change places—to change places—the so-called Freaks upon the rickety platform and the damned sniggering spectators on the tan floor!154

What is so interesting here is the emphasis on changing places, on switching audience and actors and using theatrical practice itself to bring about the very exchange it is suggesting, if not literally—the audience is not actually going to rise up and change places with the actors—then imaginatively. The cultural memory of the Victorian freak show becomes not an awkward anachronism but a potent tool as it haunts the theatre and puts the audience, which probably prided itself on having evolved superior theatrical taste to its Victorian predecessors, in the uncomfortable position of gawking at freaks just as they did. The audience viscerally experiences, not just observes, the blurring of boundaries between freakish and normal that Christine C. Ferguson describes in her study of John Merrick, the “elephant man”: “Physical normalcy and irregularity, rather than representing two permanently opposed and inherent states of being, are fluid concepts involved in a recurrent process of dialogue and mutual remaking.”155

Although the play was praised at the time, it has been virtually neglected; what little attention it has received has focused on the way in which Pinero might have been using his piece to comment on the war.156 Nadja Durbach, although apparently unaware of Pinero’s play, writes of the effect of the war on freak shows in Britain more generally: “The cataclysmic events of the First World War immediately wrought changes to the ways in which British audiences engaged with freakery. This was both because the war triggered changes to the entertainment industry that had long-term effects and because it compelled British society to engage with physical deformity in new ways.” During the war, the War Office “took control over several major exhibition venues, including the resort and theme park of Kursaal at Southend-on-Sea and the Crystal Palace in Sydenham. . . . The government encouraged the closing of fairs and shows that detracted from war work, seeking to prioritize the production of munitions and discourage leisure activities. . . . Human and animal acts in particular went into sharp decline, surviving primarily within the context of the circus.”157 The Freaks marks this transition.

Furthermore, as Sean O’Casey’s The Silver Tassie (1928) so eloquently shows, the war created a new generation of “human oddities”—the deformed, mutilated, disabled bodies that were its casualties. This meant that in addition to genetically generated anomalies, there was now a growing number of men permanently disfigured or altered by their environment, and since their deformities were inflicted in the service to their country, they occupied a higher social place than natural freaks. Durbach tracks this change and the resulting category of “disabled,” pointing out that in fact the one did not subsume the other: “Indeed, the distinction between disabled veterans and others with bodily deformities not only remained, but in many ways it intensified during the interwar period in Britain.”158 The relationship of the onlooker to the thing exhibited also changed dramatically, no longer safely distant but intimately connected as these war-deformed people were woven back into the fabric of the community and daily life, not objects up on a stage to be stared at and then forgotten.

Despite being closed prematurely, the play enabled Pinero to be rediscovered by critics who had dismissed him as merely an unsuccessful imitator of Ibsen in the 1890s. The Freaks, writes the Saturday Review critic, “teaches us how Sir Arthur should really be viewed and valued.” The characters are distinctive, the story is “ingenious,” and the play as a whole shows us “a dramatist in continuous touch with his audience.”159 The critic feels it is a bold move to introduce a group of “nature’s freaks” into a suburban household: “Nothing could seem more surely bound in the direction of crude farce. But we are speedily reassured,” as Pinero shows us their humanity in all its fullness. The review applauds the play’s “sincerity” and “honesty,” its compassion for the freaks, its genuine feeling through scenes like the one when the female contortionist begs the vicar to pray for the sick giant lying in bed upstairs—“One of the best [scenes] we have had on our stage for many years.” Yet the critic notes that part of the play’s honesty lies in its ending: the freaks are not allowed to “marry and live happy ever afterwards.” The critic does not spell out this eugenic message, but the assumption here is that the coupling of freaks with nonfreaks would never be natural or socially acceptable.160

Pinero’s “little play,” as he self-deprecatingly called it,161 is not mentioned in any of the standard works on freakery; one can only assume that it has gone unnoticed by most scholars. It is hardly better known in theatrical circles, though Griffin’s study of Jones and Pinero calls it “an extraordinary experimental play.”162 It deserves scholarly recognition and theatrical revival, not least because the play was more radical than even Pinero might have realized. It championed freaks as more human than normal people precisely at the peak of eugenic interest in both the United Kingdom and the United States, when the freak show “became a willing tool of the direst perversions of Darwinism.”163 The subsequent synthesis of Mendelian genetics with natural selection meant that “congenital disability was recast as pathology. Freak shows thus provided a counterdiscourse for the rising popularity of such notions as eugenics and the elimination of ‘invalids,’ ‘defectives,’ and ‘mutants.’” It was a culture in which “all deviances came to be seen as diseases.”164

Eugenics on Stage

The Freaks makes a fascinating and important intervention in this discourse on deviation and is one of dozens of examples of how theatre in this period engaged with eugenics, or as its founder Galton put it: “What Nature does blindly, slowly, and ruthlessly, man may do providentially, quickly, and kindly.”165 Darwin in his Autobiography says he is “inclined to agree with Francis Galton in believing that education and environment produce only a small effect on the mind of anyone, and that most of our qualities are innate.”166 A full consideration of eugenics in the theatre lies beyond the scope of this study, and the work of Tamsen Wolff has already significantly expanded our understanding of this area.167 In addition to the many playwrights she explores in her groundbreaking study Mendel’s Theatre, there are those like H. M. Harwood, Elizabeth Baker, and Adam Neave whose eugenics-themed work I briefly discuss. Others, in particular Maeterlinck, lie beyond the scope of this study; Maeterlinck’s Betrothal (1921), for instance, directed by Granville-Barker, combines eugenics, monism, and an epic theatrical vision spanning the whole of human evolution.