During Jedediah Smith’s absence in California, much history had been made, and Smith, Jackson & Sublette had been brought a long way on the road to solvency. Some of this was David Jackson’s doing; in his quiet way, he had brought in the beaver on which everything depended. But this was a year of achievement for William L. Sublette in particular.

To begin with, Sublette made a memorable fall hunt. Daniel Potts, who had not succeeded in getting off to the southwest with Jedediah Smith, ended by accompanying the junior partner, and thereby Sublette’s company acquired a historian. A reluctant historian, it is true, for Potts took his departure toward the Black-foot country only because he could make a party for no other route. Sublette, whom the Indians called “Cut Face” for a scar on his chin, or “Fate” for reasons unexplained,1 led his company north to the forks of the Snake, and then up Henrys Fork some thirty miles, after which he circled the Tetons into upper Jackson Hole. Most of the way he was harassed by Blackfeet.

In Jackson Hole, Sublette’s party again fell upon the principal branch of the Snake. They followed it up to its source, then went on north across a divide to the source of the Yellowstone, which proved to be “a large fresh water lake.... about one hundred by forty miles in diameter, and as clear as crystal.” They were the first white men since John Colter to lay eyes on Yellowstone Lake,2 and Potts’s description is the earliest of record. But Daniel Potts had a much more significant discovery to report, no hint of which had got into the legend of Colter’s wanderings:

On the South border of this Lake is a number of hot and boiling springs, some of water and others of most beautiful fine clay, resembling a mush pot, and throwing particles to the immense height of from twenty to thirty feet. The clay is of a white, and of a pink color, and the water appears fathomless, as it appears to be entirely hollow underneath. There is also a number of places where pure sulphur is sent forth in abundance.

An experience many later visitors to Yellowstone will understand:

One of our men visited one of these whilst taking his recreation—there at an instant the earth began a tremendous trembling, and he with difficulty made his escape when an explosion took place resembling that of thunder. During our stay in that quarter I heard it every day.

Evidently Sublette had reached the West Thumb of Yellow-stone Lake, its paint pots and geysers more active than now. From this time, tales about the Yellowstone would get around in the mountains, laughed at by those not simple enough to be taken in by mountain yarning; formal “discovery” of this magnificent country would not come for over forty years.

Of Sublette’s return to Cache Valley, Potts says merely:

From this place by a circuitous route to the North West we returned. Two others and myself pushed on in advance for the purpose of accumulating a few more Beaver, and in the act of passing through a narrow confine in the mountain, we were met plumb in the face by a large party of Blackfeet Indians, who not knowing our number fled into the mountain in confusion: we retired to a small grove of willows; here we made every preparation for battle—after which finding our enemy as much alarmed as ourselves we mounted our horses, which were heavily loaded, and took the back retreat. The Indians raised a tremendous yell, showered down from the mountain top, and almost cut off our retreat. We here put whip to our horses and they pursued us in close quarters until we reached the plains, when we left them behind. On this trip one man was closely fired on by a party of Black-feet; several others were closely pursued.3

Thus Sublette, late in the fall, got back to “the depot” in Cache Valley. What Jackson had been doing meanwhile remains something of a mystery: he is always a hard man to follow. It seems likely that Jackson headed for the lower reaches of the Snake Country. Who made up his party is not known, but two years later Thomas Fitzpatrick was Jackson’s clerk, and he may have acted in that capacity during all the years Smith, Jackson & Sublette operated in the mountains.4

Wherever Jackson went, whoever made up his party, he had a successful hunt. Either he returned in person to Cache Valley or he sent back an express with word of his prospects, for immediately after his own return from the Yellowstone country, Sublette took on himself the responsibility of getting the word down to Ashley. Such an express at this season involved a journey on foot, and Sublette had to go in person. He set out for St. Louis with a single companion, “Black” Harris.

Harris, the mountain men agreed, was the darnedest liar; lies tumbled out of his mouth like boudins out of a buffler’s stomach. But he was also a “man of great leg,” exactly suited to such a journey as this. His given name was Moses, and he was born, it is said, in Union County, South Carolina. He may first have gone to the mountains in 1822, and it is reasonably certain that he was one of the two men named Harris who in title fall of 1823 floated down the Missouri with John S. Fitzgerald. Beckwourth says he went to the Rockies a year later in Ashley’s party. Harris looked and was tough; the painter Alfred Jacob Miller described him as “of wiry form, made up of bone and muscle, with a face apparently composed of tan leather and whip cord, finished off with a peculiar blue-black tint, as if gunpowder had been burnt into his face.” He was a man of violent passions, but for all that, as Clyman once remarked, “a free and easy kind of soul Especially with a Belly full.”5

Wearing snowshoes, the two men set out from the valley of the Great Salt Lake on January 1,1827.6 Horses would have been able neither to travel through the snow nor to find feed, so Sublette and Harris took with them an Indian-trained packdog, on the back of which they strapped fifty pounds of sugar, coffee and other provisions. On their own backs they carried a supply of dried buffalo meat.

As far as the valley of the Green they saw no buffalo sign; they came instead on evidences that Blackfeet were in the country. It seemed expedient to leave the traveled road for “the open plains,” the approaches to South Pass south of the Sandy, where they were able to obtain water only by melting snow or ice. Of water in this form, however, there was no lack, for the whole countryside seemed drifted over with it. Two weeks’ travel brought them to the Sweetwater, and on the fifteenth day they reached Independence Rock.

From here on the journey was a rugged one, for the plains were a formidable proposition in winter. As Sublette and Harris moved down the Platte, they encountered snowdrifts which compelled them to wear their snowshoes for half a mile at a time, and there was ever less wood: often they were forced to walk half the night to keep from freezing. Near Ash Hollow they came on Pawnee sign. A large party like Ashley’s might be safe among the Pawnees, but what had befallen Jim Clyman in the summer of 1824 was a memory still fresh. Although they were beginning to stumble with weakness, Sublette and Harris veered away from the river for three days.

Afterward they fell on a large and recent trail made by Omahas. Sublette and Harris followed this trace four days before overtaking the camp. The chief, Big Elk, received them kindly, and other Indians they met subsequently were no less friendly. But the red men could afford the whites little in the shape of food. On one occasion Sublette traded his butcher knife, a mountain man’s most prized possession, for a dried buffalo tongue—a dainty he and Harris devoured on the spot.

The dog was lame and starving. Each day it fell behind, limping into camp long after dark. The two men had got as far down the Platte as Grand Island, but the two hundred miles that separated them from the settlements seemed an infinity; both were in bad shape. One night they halted at a point where three elm trees grew. Sublette had barely strength to scrape the snow from the earth, gather his blanket about him and fall exhausted to the ground, but Harris broke dead branches from the trees and kindled a fire. When the dog crawled into camp, Harris proposed that it be killed. After a long wrangle Sublette gave in. Harris snatched up his ax and struck the dog. The animal fell, but staggered to its feet. Reeling with weakness, Harris struck again and missed. At the third blow the ax flew off the handle, and the dog, howling piteously, fled into the night. The frantic Harris called for Sublette’s assistance, and the two men groped about in the darkness until they found the mourning dog. While Sublette held the animal, Harris stabbed it, then flung the carcass on the fire to singe it. But the dog still clung to life; convulsively it kicked off the fire. It was more than their nerves could stand. Sublette seized his ax and dashed in the animal’s skull.

Sublette returned to his blanket. Harris roasted the dog and set aside some of the flesh for his booshway. By morning Sublette was able to choke down a little of it. This food carried them for another two days. They staggered along, now and then seeing a bird, without being able to bring it down. They had turned away from the Platte, taking the road southeast toward the Kaw,7 but the going was desperately hard, for the snow was not crusted over sufficiently to bear their weight. They shot a rabbit, however, and soon afterward fell on a Kaw trail. The trail was a month old, but the Kaws had beaten down the snow, and they were able to make better progress. In a timbered bottom they killed four wild turkeys. That carried them to the Big Vermilion, and a few more days brought them to the Old Kaw village. Here they were fed and given something to drink, but the terrible pressure of time rode them, the necessity to be in St. Louis by March 1. Harris had sprained his ankle, but by giving up his pistol, Sublette got a horse for him to ride, and on they went, reaching the Missouri two days later. On March 4, just three days late, the two men rode into St. Louis.

This arrival was important to William L. Sublette and his partners to a degree they could scarcely have anticipated when, the previous July, they signed the contract with Ashley. For Ashley, Sublette found on reaching St. Louis, was by no means done with mountain adventures; he was full of plans to send an expedition to the Rockies which in effect would compete with Smith, Jackson & Sublette.

The idea may have been in Ashley’s mind all along, for there is a curious stipulation in the contract the General drew up with the three partners in July 1826: “it is understood and agreed.... that so long as the said Ashley continues to furnish said Smith Jackson & Sublette with Merchandise... he will furnish no other company or Individual with Merchandise other than those who may be in his immediate service.” This was enough to put the squeeze on the free trappers, who would have to deal with Smith, Jackson & Sublette or develop a supply service of their own. But for Ashley himself the arrangement left a loophole large enough to drive a wagon through. He no sooner reached St. Louis than he began loading the wagon.

On October 14, 1826, Ashley addressed a letter to the partners of the French Fur Company, Bartholomew Berthold, Bernard Pratte and Pierre Chouteau. That letter has been quoted in part on page 190, but it is significant for other reasons than its account of Ashley’s dealings the previous summer with Smith, Jackson & Sublette. The General went straight to the point:

I contemplate sending an expidition across the R Mountains the ensuing Spring for the purpose of trading for and trapping Beavers, and from a conversation had with Genl. B. Pratte a few days since I am induced to propose to you an equal participation in the adventure.

[He describes the arrangements he has made with Smith, Jackson & Sublette, including the prices at which some of the merchandise is to be delivered in the mountains, then continues:]

The expedition which I propose sending in the spring will consist of about forty Men one hundred and twenty mules & horses, the merchandise &c necessary to supply them for twelve months, and that to be furnished Messrs Smith Jackson & Sublett, all of which must be purchased for cash on the best terms.

If you are disposed to join me in the adventure you will please signify the same by letter previous to my departure for the East–––8

Here are two separate though related business undertakings. Ashley is to act as supplier for Smith, Jackson & Sublette. But his expedition is to trap as well as trade for beaver; and it is to be equipped for twelve months. The logic is apparent. If men were to be sent out to the Rockies anyway, it would be a good idea to keep them there a full year, trapping beaver the while.

The partners in the French Company took Ashley’s proposal under advisement. His rivals had been profoundly impressed with Ashley’s successes of the past two years, but the mountains had ruined everybody else who ventured into them. A further complication was that Etienne Provost was back from the mountains asking to be taken into the company.9 The partners in St. Louis wrote to Berthold, then upriver at Fort Lookout, requesting his advice. On December 9 he replied:

I dare not advise anything about the project with Ashley. However, it seems to me that it would be well for us to assure ourselves of Provost, who is the soul of the trappers of the Mountains [l’ âme des chasseurs des Montagues]..... Even if it was only to hinder the meeting between him and the Robidoux I would say it seems that he should be made sure of, unless you have other plans.10

Provost was put on the payroll, to remain the rest of his life. But the negotiation with Ashley dragged. On February 2, 1827, Ashley wrote Pierre Chouteau from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, trying to bring the business to a head.

Dr Sir

In addition to the terms of my proposition made to Messrs. B. Pratte & Co to equally participate with me in an expedition intended for the Rocky mountains—I propose to furnish what mules & horses I have (say about one hundred) with each a saddle & rope, the former at fifty five dollars & the latter at twenty five dollars pr head—all the merchandize which I now have intended for that Expedition, on terms equal to such as you may furnish similar articles for the same purpose, I will accompany the expedition as far as I may deem absolutely necessary, and receive for my personal services at the rate of two hundred & fifty dollars pr. month which sum is to be paid by Messrs. B Pratt &c—all the beaver which I may receive for debts now due me by the hunters west of the mountains shall be delivered to said concern as proposed, they accounting to me for the same at whatever price I receive it in that country which is in no case to exceed three dollars pr pound—after the conclusion of the hunt say about the first of July 1828 any remna[n]ts of merchandize or other articles (furs mules & horses for the transportation of the same excepted) is to be taken by said B Pratt & Co on their acct at a discount of thirty three & one third pr ct less than the retail price in that country & for one half of the whole amt. thereof the said B. Pratt will account to me for and pay the same at St Louis—Two confidential persons will be necessary to conduct the business to whome we must expect to pay saleries of considerable amt I should prefer Mr. August Chouteau [eldest son of Pierre Chouteau] being at the head of the business I would be willing to pay him one hundred dollars pr month for his services—The other person I will Select myself—If Mr. Chouteau or some other Gentleman equally qualified cannot be had on the terms before mentioned I would be willing to allow him or the person in charge of the business an equal participation in the profits we finding the whole capital, viz, this person to receive one third of the neat proceeds and he at the same time accountable for one third of any loss which may appear in the business—Messrs. B. Pratte & Co will not suffer any person trading for them at Taus or other place or places, directly or indirectly to interfere with the business of the proposed concern in any way whatever—or allow them to persue a similar business in the same section of country—my [word lost by seal] will not permit me at preasant to enter more minutely into the articles of the proposed assoseation, the outlines being understood, articles of a minor nature can be specifyed at St Louis—I must require of Mr. Chouteau an answer to this proposition in positive terms, befor I leave Pittsburg say by the 15th next—my health is much better than when I left Phia—I shall go directly to Pittsburg––11

Replying from Philadelphia on February 10, Chouteau observed that in all their conversations the difficulty had been to decide who should conduct the enterprise. “I am convinced that with you in charge of the Expedition, you would prove of great service, not only in deciding upon the route to be followed, but to instill order and obedience, which are indispensable in a voyage of this sort. But you are aware General that your presence would be still more necessary in crossing the Mountains & for transactions with the Hunters, than it would be elsewhere.” He proposed that they wait on the return of both to St. Louis, when an hour’s conversation would be more effective than volumes of correspondence in deciding on a head for the expedition.12

Ashley went on back to St. Louis. There, on February 28, in the presence of Bernard Pratte, he drew up a memorandum covering the main points of the discussions previously had. Down to this moment, four days before Sublette reached St. Louis, the project still hung fire, for the memorandum ended, “should Genl. Pratte exceede to these propositions, it will be necessary immediately to enter into articles of agreement.”13

Unless it had been clearly understood the year before that Ashley reserved the right to trap on his own account, Sublette must have objected strenuously to any such project as he found shaping up in St. Louis. What it amounted to was that Smith, Jackson & Sublette, by purchasing goods through Ashley, underwrote the expenses of a rival operation. Sublette may have threatened to look for backing elsewhere, with good prospects of finding it despite the circumstance that the firm’s returns for the present year were committed to Ashley. Another possibility is that Chouteau’s reluctance to enter on an arrangement for a trapping venture which did not require Ashley’s return to the mountains proved to be an insuperable obstacle. A final possibility is that Sublette made so good a proposition to Ashley that the General gave over his own plans.

This third idea has to be taken seriously, for there are facts to support it. The proposition might have shaped up like this: Merchandise to the amount of $15,000 would be taken up to the mountains this spring and the furs brought down in late summer. When the caravan reached Missouri, probably about the end of September, Ashley would meet it with an outfit for 1828. Smith, Jackson & Sublette would buy from Ashley all his mules and horses and use them to transport the new outfit back to the Rockies immediately. This would save the expense of wintering the pack animals in Missouri; it would return them to the mountains where an unfailing demand existed; and it would save the trouble of sending outfit 1828 to the mountains next spring. Above all, it would remove Ashley from the operating end of the business. Smith, Jackson & Sublette would find a new function for him; hereafter Ashley would serve as agent in marketing their furs.

The arrangement just described actually materialized, but we may never be sure to what extent the details were worked out beforehand. At any rate, nothing more is heard of Ashley’s proposal to trap in the Rockies for a year, and the agreement he reached with the Chouteau interests was limited to the delivery in the Rockies of the goods ordered by Smith, Jackson & Sublette.

Courtesy, Bureau of American Ethnology.

CROW INDIAN, ET-TISH-EASTER-KO-KISH OR SPOTTED RABBIT

Photo by De Lancey Gill, 1910.

Courtesy, Coe Collection, Yale University.

GIVING DRINK TO THIRSTY TRAPPERS

Alfred Jacob Miller, 1837.

Courtesy, U.S. Forest Service.

THE FALLS OF THE POPO AGIE

Photo by A. H. Carhart, 1922.

Courtesy, U.S. Forest Service.

STRAWBERRY POINT, UPPER VIRGIN RIVER

Photo by Paul S. Bieler, 1941.

For this limited undertaking the French partners named as their agent James B. Bruffee, and Ashley picked as field commander Hiram Scott, one of the two captains (with Jedediah Smith) who had commanded his men in the campaign against the Rees.14 The party got off from St. Louis late in March 1827 and, a distinct novelty, took along a piece of artillery, a four-pounder, mounted on a carriage drawn by two mules—the first wheeled vehicle that ever crossed South Pass.15 (It was this cannon which saluted Jedediah Smith on his return from California.) Ashley accompanied the party only to the frontier in consequence of his “verry bad health,” but he got the expedition off confident it was in good hands. “Messrs Bruffee & Scott appears alive to our intrest,” he wrote the Chouteaus from Lexington on April 11, “the latter is entirely efficient & if properly supported by the former will keep all things in their proper channel.”16

One detail William L. Sublette had to attend to personally was a license to trade with the Indians. Issued March 26, 1827, the license authorized Smith, Jackson & Sublette to trade for two years at “Camp Defence [Defiance], on the waters of a river supposed to be the Bonaventure.—Horse Prairie, on Clark’s river of the Columbia, and mouth of Lewis’ fork of the Columbia.” The first location undoubtedly was the place of rendezvous in Cache Valley (Bear River as yet was shown on no maps, and the Buenaventura served to approximate the location for official purposes). Jedediah had some firsthand acquaintance with Horse Prairie, which was located a few miles east of Flathead Post. But none of the American trappers, to the time Sublette left the Rockies, had yet worked the country about the mouth of the Snake, the near vicinity of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Fort Nez Perces. This may have been Jackson’s objective at the time he and Sublette parted from Jedediah Smith at the rendezvous of 1826. The amount of capital employed was stated in the license as $4,335, which would seem to have been a gross understatement.17

Scant enough is the information as to what was happening in the mountains while Jedediah Smith was working his way north through California and William L. Sublette was wrestling with the destinies of the partnership in the lower country. Jackson presumably spent the time clearing off any beaver which remained on the Weiser, the Payette and the Boise after Alexander Ross’s summer hunt of 1824 and Jedediah’s spring hunt of 1826.18 He lost no men and got back to rendezvous with good returns. The only definite information regarding the movements of any of the trappers is furnished by Daniel Potts. His narrative is worth quoting; he participated in an exploration which corrected a misconception Jedediah Smith had entertained about the course of the Sevier River, and he describes one of the first trapping forays into central Utah:

Shortly after our arrival last fall in winter quarters, we made preparations to explore the country lying south west of the Great Salt Lake. Having but little or no winter weather, six of us took our departure about the middle of February, and proceeded by forced marches into the country by way of the Utaw Lake—which lies about 80 miles south of the Sweet Water [Bear] Lake, is thirty miles long and ten broad. It is plentifully supplied with fish, which form the principal subsistence of the Utaw tribe of Indians. We passed through a large swamp of bullrushes, when suddenly the lake presented itself to our view. On its banks were a number of buildings constructed of bullrushes, and resembling muskrat houses. These we soon discovered to be wigwams, in which the Indians remained during the stay of the ice. As there is not a tree within three miles, their principal fuel is bullrushes.

This is a most beautiful country. It is intersected by a number of transparent streams. The grass is at this time from six to twelve inches in height, and in full bloom. The snow that falls, seldom remains more than a week. It assists the grass in its growth, and appears adapted to the climate.

The Utaw lake lies on the west side of a large snowy mountain [the Wasatch Mountains], which divides it from the Leichadu [Green River]. From thence we proceeded due south about thirty miles to a small river [the Sevier] heading in said mountain, and running from S. E. to S. W. To this I have given the name of Rabbit river, on account of the great number of large black tail rabbits or hares found in its vicinity. We descended this river about fifty miles to where it discharges into a salt lake, the size of which I was not able to ascertain, owing to the marshes which surround it, and which are impassable for man and beast. This lake is bounded on the south [north] and west by low Cedar Mountains, which separate it from the plains of the Great Salt Lake. On the south and east also, it is bounded by great plains. The Indians informed us that the country lying southwest, was impassible for the horses owing to the earth being full of holes. As well as we could understand from their description, it is an ancient volcanic region. This river is inhabited by a numerous tribe of miserable Indians. Their clothing consists of a breech-cloth of goat or deer skin, and a robe of rabbit skins, cut in strips, sewed together after the manner of rag carpets, with the bark of milk weed twisted into twine for the chain. These wretched creatures go out barefoot in the coldest days of winter.’ Their diet consists of roots, grass seeds, and grass, so you may judge they are not gross in their habit. They call themselves Pie-Utaws, and I suppose are derived from the same stock.

From this place we took an east course, struck the river near its head, and ascended it to its source. From thence we went east across the snowy mountain above mentioned, to a small river [the Frémont River] which discharges into the Leichadu. Here the natives paid us a visit and stole one of our horses. Two nights afterwards they stole another, and shot their arrows into four horses, two of which belonged to myself. We then started on our return. The Indians followed us, and were in the act of approaching our horses in open daylight, whilst feeding, when the horses took fright and ran to the camp. It was this that first alarmed us. We sallied forth and fired on the Indians, but they made their escape across the river.

We then paid a visit to the Utaws, who are almost as numerous as the Buffaloe on the prarie, and an exception to all human kind, for their honesty.19

Bear Lake, site of rendezvous this year, lies within the great bend of the Bear River, nearly bisected by the Utah-Idaho boundary along the forty-second parallel. The lake was probably discovered by the Nor’Westers, for Alexander Ross prints a letter written by Donald Mackenzie on September 10, 1819, from “Black Bears Lake,” and in his account of his own adventures in the summer of 1824 Ross writes that his party considered proceeding “by the Blackfeet river to . . . Bear’s lake, where the country was already known.” Still, it is curious that William Kittson, who was a member of Mackenzie’s party in 1819-1820, should later have drawn a map of the Bear River country which has no intimation that such a lake existed. For the Americans, Bear Lake undoubtedly was discovered by Captain Weber in the fall of 1824, because Jim Beckwourth calls it “Weaver’s Lake.” The lake had many other names—Little Lake, Sweet Lake and Sweet Water Lake (all serving to distinguish it from Great Salt Lake), Little Snake Lake and Trout Lake; it is one of the most beautiful bodies of water in the West, its waters profoundly blue under the sienna hills. Rendezvous was at the south end of the lake, near present Laketown. A trail south from Bear River ran along the west shore of the lake, and it was by this trail, undoubtedly, that the lake was first discovered, but it could also be approached from the east over a ridge, and from the west by the canyon of Blacksmiths Fork—the way Jedediah was led by his Snake guide on his return from California.20

The ingathering of the trappers at Bear Lake began in June, and was attended with a degree of excitement. Potts relates that a few days before his own return from the trapping expedition into central Utah

a party of about 120 Blackfeet approached the camp & killed a Snake Indian and his Squaw. The alarm was immediately given and the Snakes, Utaws and whites sallied forth for battle—the enemy fled to the mountains to a small concavity thickly grown with small timber surrounded by open ground. In this engagement the squaws were busily engaged in throwing up batteries and dragging off the dead. There were only six whites engaged in this battle, who immediately advanced within pistol shot and you may be assured that almost every shot counted one. The loss of the Snakes was three killed and the same number wounded; that of the whites, one wounded and two narrowly made their escape; that of the Utaws was none, though they gained great applause for their bravery. The loss of the enemy is not known—six were found dead on the ground, a great number besides were carried off on horses.21

Jim Beckwourth participated in this battle, and the account he gives of it illustrates the facility with which he embroidered the facts; the fruits of victory, Jim says, “were one hundred and seventy-three scalps, with numerous quivers of arrows, war-clubs, battle-axes, and lances..... The trappers had seven or eight men wounded, but none killed. Our allies lost eleven killed in battle.” But Beckwourth does furnish two details to amplify Daniel Potts’s factual report: the scene of the fight was the shore of Bear Lake, perhaps five miles from camp, and William L. Sublette took a valiant part in the battle.22

Participation of Utes in the fight is the more interesting because a rumor of treaty making with that tribe penetrated all the way to Mexico and gave rise to diplomatic representations. The degree of exaggeration in those representations was something in which Beckwourth himself could have taken a just pride. The Mexican Secretary of State wrote the American minister on April 12, 1828, of intelligence lately received that

at four days’ journey beyond the lake of Timpanagos, there is a fort situated in another lake, with a hundred men under the command of a general of the United States of North America, having with them five wagons and three pieces of artillery; that they arrived at the said fort in May, and left it on the 1st of August of the year last past, with a hundred horses loaded with otter skins; that the said general caused a peace to be made between the barbarous nations of the Yutas Timpanagos and the Comanches Sozones, and made presents of guns, balls, knives, &c., to both nations; that, of the above-mentioned hundred, five-and-twenty separated themselves to go into the Californias; that the Yuta Timpanago Indian, called Quimanuapa, was appointed general by the North Americans, and that he states the Americans will have returned to the fort by the month of December.23

Such happenings as these, and especially “the iruption of the twenty-five men into the Californias,” were calculated to disturb the tranquillity of the republic, and the American minister was informed that “necessary measures” would be taken. He, however, replied suavely that on examining Melish’s map of North America, he found the dividing line between Mexico and the United States to pass through the lake of Timpanagos.

Any point, therefore, four days’ journey beyond that lake must be situated within the territory of the United States; and the only act set forth in your excellency’s note of which this Government has any right to complain, is that of the entrance of the twenty-five men into California without passports.

Infractions of the laws of Mexico were to be deplored, but hunters passed the boundary of the United States ignorant that they were doing wrong, and pursued their hunting excursions within the territories of Mexico unaware that they were committing a trespass.24

Thus the far, faint international repercussions of the activities of Smith, Jackson & Sublette in the West. The gathering at Bear Lake was in fact a trespass on the soil of Mexico, for the site of rendezvous was some fifteen miles south of 42°, but no one knew where that vague abstraction, the boundary line, really ran. No one much cared. Effective sovereignty was exercised here by no nation; law was what could be agreed on with friendly Indians or enforced on hostile Indians.

More important to mountain history was the developing economics of the fur trade. The varied years since Ashley set out for the mountains had brought complications which by the time of rendezvous in 1827 were exerting a powerful pressure on the trade.

Ashley had introduced free trappers into the mountains in 1822-1823. The price for beaver then fixed, $3.00 a pound, held down to the flush times of 1833-1834, when under the pressure of competition it rose to $5.00 a pound in merchandise, $3.50 a pound in cash.25 Since the price was fixed without regard to the fluctuating market value of the fur, the variable became the price of the goods which were exchanged for beaver. A good market for beaver just possibly might bring lower prices for goods; a poor market most certainly would result in higher prices.

When he sold out to Smith, Jackson & Sublette in the summer of 1826, Ashley stipulated that payment was to be made in beaver delivered at the mountain price, that is, at $3.00 a pound. (He was alternatively willing to transport it to the States and sell it for them, charging them $1,125 a pound for transport, which shows that Ashley was serious when he said, as he once did, that he would gladly pay $1.00 a pound to have beaver delivered in St. Louis from the mountains.)26 Obviously, if the new partners paid the free trappers $3.00 a pound for their beaver, then turned around and sold it to Ashley at the same price, there was nothing in the deal for them. Their whole margin had to come from the goods they sold. Ashley had therefore stipulated also that he would supply goods to no other company or individual. Unless and until competition showed its face in the mountains, the free trappers would have to deal with Smith, Jackson & Sublette.

There was one other factor in this situation—men who were hired by the year and whose beaver catch, if any, was the property of the company. Engagés had always been necessary around the fixed posts, and they may not have been dispensed with when Ashley’s men cut loose from their bases on the Missouri and the Yellowstone; camp tenders and horse wranglers as well as trappers were important to a hunt. And a certain number of engaged men was essential. Otherwise a brigade could go nowhere except by common consent. When Jedediah Smith returned to the mountains as Ashley’s partner in the fall of 1825, a considerable proportion of his men, perhaps as many as forty-two, were engagés.27

Some of the men may have been hired at a fixed annual wage, say $200 a year.28 Others may have been paid a minimum annual wage, plus a percentage of the value of the beaver they caught. When the engagements of his men ran out on the Oregon coast in July 1828, Jedediah agreed to pay ten of them $1.00 a day until they should get back to rendezvous,29 but whether this was typical of contractual engagements it would be hard to say.

Throughout this period, however, the backbone of the trade remained the free trapper, who might attach himself to a brigade yet retain the right to deal independently with company partners or clerks in the sale of his beaver. And the free trappers, at rendezvous 1827, began getting an education in the manipulation of prices. That Smith, Jackson & Sublette were under heavy pressure themselves did not make the free trappers feel more kindly about it.

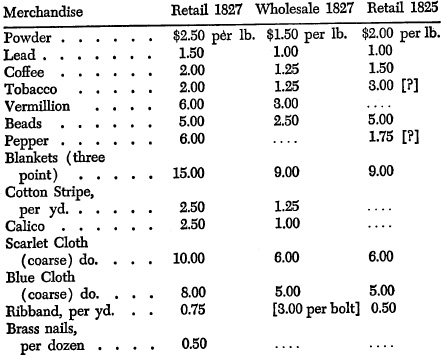

A table will illustrate what happened to prices in the mountains between 1825 and 1827. The first column lists the retail prices noted by Daniel Potts at rendezvous in 1827; the second column shows the prices at which Ashley agreed to deliver goods under the contract of July 18, 1826; the third column lists prices for the same goods found in Ashley’s accounts of 1825.

No wonder Daniel Potts exclaimed that there was a poor prospect of making much money in the mountains; he cited the price of goods and horses, saying that horses cost from $150 to $300 apiece, and some sold as high as $500. (Potts lost one horse on the Yellowstone hunt and two on the central Utah hunt; his loss, he said, could not be computed at less than $450.)30

Potts was not the only one to resent the sudden upward surge of prices. We shall see in Chapter 13 that rising American prices and lowered British prices did much to alter the balance of economic force in the mountains. Meanwhile, observe Peter Skene Ogden entering in his journal on January 5, 1828, reports which had reached him of developments at the American rendezvous the previous summer:

. . . altho our Trappers have their goods on moderate terms, the price of their Beaver is certainly low, compared to Americans, with them Beaver large & small are averaged at five Dollars each, with us two Dollars for a Large and one Dollar for a small Beaver here then there is certainly a wide difference . . . it is optional with them to take their furs to St. Louis where they obtain five & half Dollars pr. lb., one third of the American Trappers follow this plan, it is to be observed goods are sold to them at least 150 p.Cent dearer than we do, but again they have the advantage of receiving them on the waters of the Snake Country and an American Trapper, from the short distance he has to travel, not obliged to transport provisions, requires only half the number of Horses we do, and are also very moderate in their advances, for Three years prior to the last one, General Ashly Transported supplies to this Country and in that period has cleared Eighty Thousand Dollars and retired, selling the remainder of his goods on hand at an advance of 150 Pr.Ct. payable in five years in Beaver at five Dollars per lb. or in cash optional with the purchasers, Three young men Smith, Jackson and Soblitz purchased them, and who have the first year made a gain of twenty Thousand Dollars, it is to be observed, finding themselves alone, they sold their goods one third dearer than Ashley did, but have held out a promise of a reduction in their prices this year, What a contrast between These young men and myself, They have been only six years in the Country, and without a doubt in as many more will be independent men. . . ,31

Ogden’s envious view of his young American rivals was a little astigmatic, but 1827 brought them over the hump. At Bear Lake, Jackson and Sublette delivered to Bruffee, as agent for “W. H. Ashley & Co.,” 7,400⅓ pounds of beaver at $3.00 a pound, together with 95 pounds of castor at the same price, and 102 otter skins at $2.00 each, the proceeds of the year’s hunt totaling $22,690. At the same time they accepted delivery on merchandise invoiced at $22,447.14, plus 5 horses valued at $30 each. There were some sundries among both the credits and the debits, but these balanced out at $22,929.32 Apparently the invoice of merchandise delivered included the note given to Ashley the previous year, for the Sublette papers contain a quit claim by Ashley dated October 1, 1827, which says that if in July 1826 Smith, Jackson & Sublette gave a note in Ashley’s favor for $7,821, “a ballance then due by them to me now therefore if any such note was given it is to be considered en-tir[e]ly void as they the said Smith Jackson & Sublette have since paid said amount.”33

All this had been the doing of Jackson and Sublette, for the proceeds of Jedediah Smith’s spring hunt of 1827 were still in California. On the whole, the partners had had an encouraging first year, and they were prepared to undertake something more ambitious. This year it had suited their convenience to hand over their beaver in the mountains at $3.00 a pound, letting Ashley run the risk and assume the expense of transport. Next year one of the partners would take down the year’s hunt, and they might have a try at marketing their beaver themselves.

One detail remained, getting outfit 1828 up to the mountains this fall. It seems likely that an arrangement was entered into with Hiram Scott to handle this business for the partnership, for Scott came to a tragic end on the Platte next year, and this was the only opportunity that offered for him to get back to the mountains. He may, however, have returned in the capacity of clerk. If so, Jackson himself must have gone down with Bruffee and come back in charge of the outfit. Ashley says that he met the incoming party with everything necessary for another outfit, and that, turning back with the same horses and mules, they reached the mountains by the last of November. However, Peter Skene Ogden was informed in February 1828 that the American “Traders from St. Louis. . . . did not return last fall. . . . [owing to] the severe Winter.” En route back to the mountains, this party seems to have lost a few horses to Pawnees; otherwise, nothing is known of their experiences.34

Rendezvous broke up July 13, 1827, ten days after Jedediah’s arrival from California. The partners had made their plans.

Sublette was to take another party north, all the way to the Blackfoot lands; the opportunity might have arisen to open trade with these Ishmaelites. Jackson went down to Missouri and back, or more probably he spent the fall in the Utah country, wintering at “the depot” on Bear River. Robert Campbell seems to have remained with Jackson until the spring hunt of 1828, when the young Irishman took a party north to the Flathead lands.

Re-outfitted with eighteen men and supplies for two years, Jedediah proposed to rejoin his men in California, then trap his way up the California-Oregon coast to the Columbia. If he got back to rendezvous, which again next year would be held at Bear Lake, well and good. If not, his partners would see him in two years