Milk

Every day at about eleven forty-five, just over halfway through fourth period, everyone in Kazuo’s classroom began to grow restless.

That was because their attention would shift to the smells drifting down the hall from the large room where their lunches were being made. They would forget about their studies as they tried to guess what the day’s meal might be. They had, of course, received a menu from the teacher at the beginning of the month. It was printed on cheap brown paper and was also posted at the back of the classroom. But nobody ever actually looked at that sheet. The reason was that looking at the monthly menu took half the fun out of eating lunch. Everybody knew that imagining what was for lunch, based on the smells drifting in from the kitchen—just when everyone was beginning to feel hungry—was the first step in enjoying the school lunch.

Kazuo felt strongly that school lunch was a very big deal. The school lunch program had started after the war so that everybody, even children from poor families, could eat at school. Every day from Monday through Friday, everyone—from students to teachers to the principal—ate exactly the same thing.

One morning, as Mr. Honda explained how to multiply numbers with two digits, Kazuo only pretended to study the blackboard. He was trying with all his might to identify the day’s main dish.

Typically, if the smell was curry, everyone would smile. That meant the day’s menu was curry stew. All the children would suddenly become diligent students, their pencils scribbling twice as fast in their notebooks so they could eat sooner. At lunchtime, even children who never asked for seconds would jostle for a spot in line to get another helping.

On the other hand, if the hallway smelled strongly of soy sauce, gloom would instantly descend. A strong soy sauce smell meant that the meal was boiled seaweed and vegetables, which didn’t have a single fan among the students, including Kazuo.

But most of the time, Kazuo thought the food in school lunch was delicious. And because of school lunch, he got to discover foods he had never tasted before—even foods from American TV shows. For example, he had seen spaghetti on the comedy program The Three Stooges, which always featured three men raising a ruckus with foolish antics. At first, Kazuo had not known the dish was called “spaghetti.” He’d only known that noodles piled on a dish were eaten laboriously with a fork by a guy named Curly, who was a big blockhead.

So in the spring of his second-grade year, when a mass of fat noodles, thinner than yet thicker than , were served to Kazuo on his metal school lunch plate, he was excited. He was going to eat the same food as blockheaded Curly! Kazuo had poked Nobuo in the seat next to him and asked if he knew the name of the odd-looking noodles with red sauce.

“Spaghetti, of course!” Nobuo had flared his nostrils and grinned confidently. “You should know better than to ask that question of a butcher’s son.”

Kazuo wasn’t sure how being a butcher’s son related to spaghetti, but he was impressed that Nobuo knew the name of this foreign food.

Still, school lunch had one flaw. The name of that flaw, which was enough to bring disgusted looks to students’ faces when they said it, was .

Miruku, or “milk,” referred to a certain lukewarm, white liquid passed out in metal cups to everyone. The substance was nothing at all like cow’s milk, commonly known in Japanese as gyunyu. This other drink was so unlike gyunyu that it had to have its own name—a name reserved for powdered skim milk.

Just how disgusting was it? First, Kazuo had decided that it gave off exactly the same foul smell as a kitchen drain. Second, when he managed to take a drink despite the smell, a very strange sweet and sour taste filled his mouth. If he left his miruku until the end of the meal, with the plan to swallow it all in one big gulp, it would congeal completely and taste exactly like melted butter mixed with water.

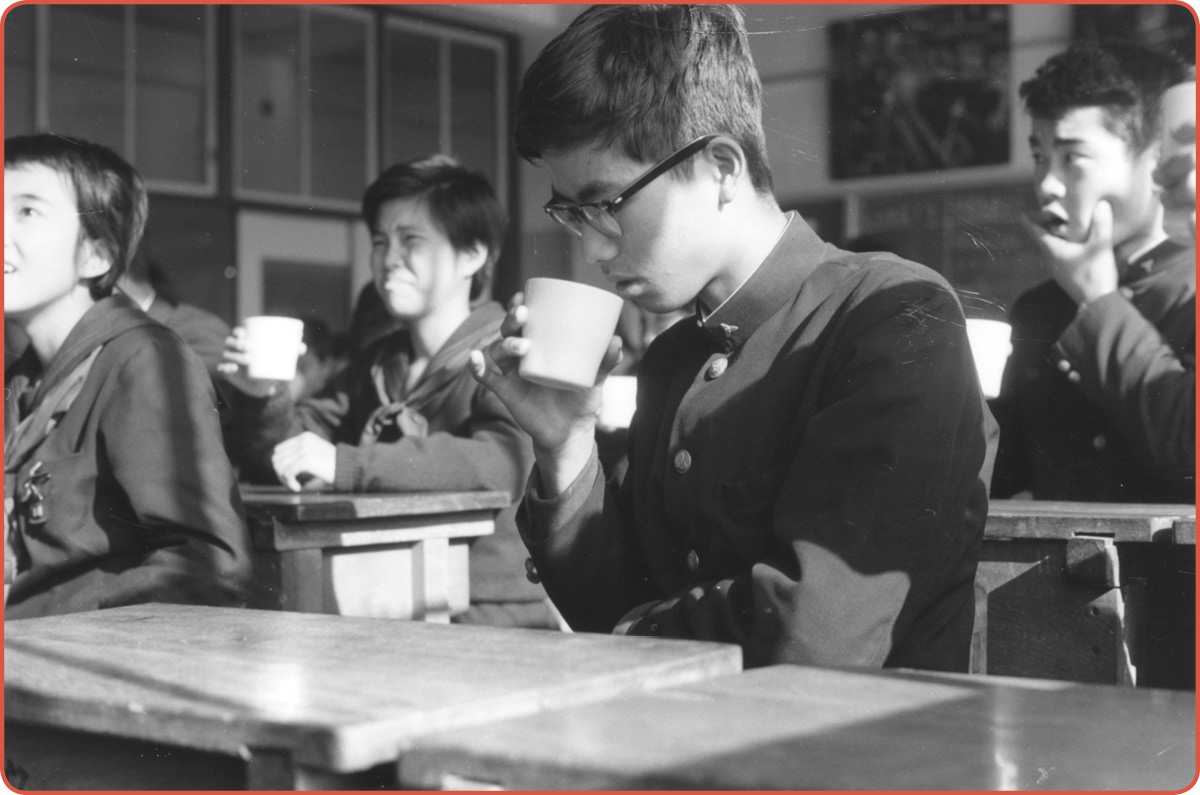

Middle school students drinking their miruku.

Unfortunately, Kazuo’s previous teacher, Mr. Tanaka, had flown into a terrifying rage the year before, yelling at the class one day when they’d refused to drink the miruku.

“All of you are spoiled rotten! When the war was on, people on the battlefield had to drink mud to quench their thirst. If you can’t drink a cup or two of this milk, what does that make you? All of you, drink! Until everyone drinks, no one leaves this classroom for lunch recess!”

Frightened by Mr. Tanaka’s outburst, Kazuo and his classmates had taken their cups of miruku back to their seats and somehow forced it down.

And for the rest of the year, the miruku had to be drunk. Kazuo and the other boys in his class had begun to hold contests to see who could drink the most. After they’d eaten the food, they had dared each other to drink as much as possible of the completely cooled, leftover miruku to demonstrate fortitude. The game was put to an end when Yukichi Nakajima, the class tough guy, drank four cups of miruku and then had an upset stomach for a week.

After Mr. Honda became their teacher at the beginning of fourth grade, Kazuo’s class no longer had to drink all of their miruku. Mr. Honda was a man of about thirty who never raised his voice. During their first lunch period as fourth-graders, after everyone had said “ at the start of the meal, Mr. Honda had told them, “Everyone, before you eat, please watch me.”

Mr. Honda brought his cup of miruku to his mouth and, holding his nose, gulped it down. When he finished, he laughed and said, “Wow, that was disgusting!”

Everyone in the class, including Kazuo, laughed heartily. With a single phrase, Mr. Honda had broken the spell cast by Mr. Tanaka.

“No one, including myself, likes the taste of miruku,” Mr. Honda said quietly. “This is not milk. And this kind of powdered skim milk is completely different from what you would find in a store. It is nothing but the sediment left over from making butter, which has been dissolved in hot water. In the United States, this kind of powdered skim milk is actually fed to cows.”

“Fed to cows!” the class cried.

“Settle down, everyone.” Mr. Honda held up a hand. “Our fifth period class is social studies, so after lunch, I will talk with you about why something that is used as feed for American cattle is being given to us for lunch. But now, about this miruku. Those of you who can drink it, please do so. But if you cannot drink it, please do not force yourself. As your teacher, I will not scold you if you leave it in your cup. I do ask, however, that you remember the lunch ladies who worked hard to prepare it for you. If you choose to leave it, please say a silent word of apology to them before doing so.”

Everyone obediently nodded.

And after lunch recess, Mr. Honda explained further. He told the children that Japan had been faced with a serious food shortage after World War II. Many Japanese children were suffering from malnutrition. So large quantities of canned fish and powdered milk had been donated, and miruku became part of a new school lunch program. It was a desperate time, and even feed for cattle was accepted with gratitude.

But twenty years had passed since the end of the war, thought Kazuo. The Olympics had even been held in Tokyo, and Japan was economically better off than before. So why was miruku still being served? The reason was that Japan had signed an agreement with the United States. It promised that American soldiers could be stationed inside Japan, and in return, if Japan were attacked by another country, America would defend Japan. As payment for this alliance with the U.S., Japanese elementary school children had to drink “powdered skim milk” every day.

After hearing Mr. Honda’s lesson, Kazuo was very upset. He felt the situation was completely unfair.

That evening at dinnertime, Kazuo told his parents and Yasuo what he had learned.

His parents reacted much less strongly than he had expected.

His mother tamped his father’s rice into a bowl. As always, she said, “During the war and afterward, people had nothing to eat at all. We’re lucky to have what we have.”

His father, whose face was red again from drinking beer, said, “I wonder if Mr. Honda is a Communist,” and brought a bite of rice to his mouth.

Yasuo was the only one to agree with Kazuo. “I hate that awful miruku. The smell of it alone makes me want to throw up. If that agreement with America ever goes away, maybe miruku will go away, too.”

But Kazuo did not think that the agreement would disappear anytime soon. So he tried to teach himself to forget about the miruku that always accompanied the school lunch.

Today, what he detected in the smells wafting through the hallway was soy sauce fried in oil.

fried whale, he thought.

was the meat that was served most often in school lunches. Deep fried whale, whale cutlets, boiled whale. Kazuo would have preferred chicken and pork, or beef, but the budget for school lunch rarely allowed for that.

Even Nobuo, the son of a butcher, said he had never eaten beefsteak. And he ate chicken and pork so few times each month that he could count them on his fingers.

Today’s food was placed on Kazuo’s metal tray by a classmate on lunch duty, a boy wearing a white apron. It was, just as he had detected, whale meat in a thick breading. Next to the whale meat was bread, and next to that was the miruku.

“Itadakimasu.” A student leader said the word of thanks, and the class repeated it. Kazuo held his nose, just as Mr. Honda had done, and downed his tepid miruku to get it over with. Then, sighing with relief, he looked down at the piece of fried whale. He could tell that it would be as tough as the sole of a shoe, as usual.

Still, Kazuo put the meat in his mouth and chewed laboriously. He couldn’t help but think about how tender and delicious real beefsteak must be.