J-Boys

That November Kazuo made two new friends.

One was a tall, sturdily built boy named Minoru Kaneda, and the other was Minoru’s physical opposite, a skinny boy named Akira Nishino. Kazuo got to be friends with Minoru and Akira after being assigned to the same small group for a class project. Also in the group was Keiko Sasaki, who lived in company housing just like Kazuo. Keiko was the group leader, and Kazuo was the assistant leader.

Nobuo was disappointed that he did not get to be in the same group as Kazuo. But he was glad to make two new friends too.

MINORU AND THE SCRAP CART

Five months earlier, on a Saturday in June, something had happened to make Kazuo want to be friends with Minoru. Kazuo had spent the afternoon rambling through the streets of West Ito, doing nothing in particular, and had ended up on top of the hill in District 4. There had been days and days of gloomy rain, and he was staring at the big houses with yards, watching the town below him gradually light up in the sunshine. Whenever he stood here, looking out from this height, Kazuo felt like a bird soaring through the sky. Sometimes he would pick out different tiny roofs in the town and imagine what kind of people lived underneath them and what they might be doing.

Kazuo felt a thin layer of sweat form on his forehead. The June sunlight was growing stronger. He closed his eyes against it, and behind his eyelids, the light seemed to gather various sounds: people’s voices and footfalls, car engines, the rustling of leaves. . . .

Chirin, chirin.

Somewhere in the mixture of sounds, he heard the faint ringing of a bell.

Kazuo opened his eyes. It was a brass bell from a two-wheeled cart piled high with bundles of old newspapers and magazines. Pulling the cart was a man. He wore a towel tied around his head and a dirty white T-shirt. Like a snail, he was inching ever so slowly up the slope.

“It’s a scrap man,” murmured Kazuo.

Scrap men bought people’s old magazines and newspapers, empty bottles, iron scrap, and other unneeded items for low prices. On days when the weather was good, they walked through town pulling their carts, ringing a bell and calling, “Scrap man, will haul! Scrap man, will haul!”

Today, now that the weather had finally cleared, they were probably trying to catch up on work they had missed due to the rain.

Even Kazuo, at the top of the hill, could see that the cart, loaded with newspapers, was hindering the man’s progress. For every step he took up the hill, the cart seemed to pull him a half step back down.

That’s got to be hard, thought Kazuo. A moment later he realized there was someone else behind the cart.

That person was pressing both hands against the back of the cart and digging into the ground with both legs. His face was hidden behind the mountains of old newspapers. But with every step he took, his head—wrapped, like the scrap man’s, in a towel made into a headband—bobbed up and down like a buoy.

After the two people had climbed slowly for a while, they stopped next to a telephone pole. They removed the towels from their heads and wiped the sweat from their faces.

Kazuo gasped in surprise. The scrap man’s helper was his own classmate, Minoru. Kazuo instinctively ducked behind another telephone pole, hiding himself.

who had grown up in Japan and lived in a neighborhood of shacks with tin roofs. It was the Korean quarter, located down the Haneto River, with its many small and medium-sized factories.

Minoru was completely hopeless at studying, but he was the biggest boy in fourth grade and so good at that no one could defeat him. That had bothered Yukichi, the toughest kid in Kazuo’s class. So one time, Yukichi had invited Minoru over to the sandbox during lunch recess. Yukichi’s older brother Masato, a very large fifth grader, had been waiting there.

“Hey, Minoru! I hear you said you never lose at sumo,” Masato said, giving Minoru a hard stare.

“I didn’t say I never lose. I said I was good at sumo, that’s all.” Minoru hunched his shoulders tensely on either side of his round, plump face.

At the start of fourth grade, Kazuo’s teacher, Mr. Honda, had said, “For the next year, you and I will be studying together. So I would like to get to know each of you well. To help me with that, please tell me something you are good at. Maybe you are good at drawing comics, or you’re an expert on baseball players—it can be anything at all.”

At that time, Minoru had answered that he was good at sumo. Now Yukichi and Masato were using Minoru’s answer as an excuse to bully him.

“If you’re so good at sumo,” Masato went on, “why don’t you and I have a match right here? I’ll help you find out just how strong you are.”

In a corner of the sandbox, Masato began to warm up like a professional sumo wrestler. He stood with his legs apart and bent his knees. Then he lifted one leg at a time out to the side, his hands on his thighs.

Kids began to gather around.

Yukichi smiled slyly, putting an arm around Minoru’s shoulders as if they were the best of pals. “How about it, Minoru? If you’re so good at sumo, have a go with my brother.”

Minoru twisted his lip and answered in a shaky voice. “Well, okay, but just once.”

“Face your opponent!” At the command of Yukichi, who had assumed the role of referee, the two boys crouched in starting positions and touched the ground with their fingertips. Masato instantly leaped up and charged into Minoru. He grabbed Minoru’s belt with his right hand, trying to knock him over.

“Uh oh, Minoru’s going down!” everyone thought.

But a second later, the boy who hit the sand was not Minoru. It was Masato.

Minoru had waited until Masato was off-balance from trying to push him over. Then he’d thrown down the older boy.

Masato got to his feet, his entire back covered in sand. “I wasn’t ready. One more round.”

Masato again prepared to fight. This time he charged at Minoru while pushing at him in various places with his hands. But without retreating even one step, Minoru took the pushes in stride and grabbed Masato’s body. As before, Masato ended up on his back in the center of the sandbox.

Furious to have lost twice in a row to a younger kid, Masato’s face turned bright red. “One more round,” he shouted, charging at Minoru. But the result was the same. In an instant, Masato went sprawling in the sand.

Everyone in Kazuo’s class, except Yukichi and a few of his friends, applauded for Minoru, who had defeated a fifth-grader three times. But being beaten so easily by a fourth-grader was more than the giant Masato could take.

Standing up slowly, Masato spit in the sand. “Stupid Korean! He stinks so much of garlic, you can’t even wrestle him.”

Minoru’s round face, which always smiled good-naturedly and never showed anger, suddenly turned fierce. Then as Minoru clenched his jaw and glared at Masato, his face slowly crumpled. Standing there in the middle of the sandbox, he hid his face in the crook of his right arm.

He’s crying, Kazuo realized.

Masato started mocking him again. “Korean pig. Korean pig!”

“Shut your trap, you jerk! What did Koreans ever do to you?”

A girl suddenly came flying out of the group gathered around the sandbox and went toward Masato. It was Hanae Yanagi, a realtor’s daughter, and one of the top students in Kazuo’s class.

But before she could reach the fifth-grader, a furious voice boomed across the playground.

“What are you doing over there?”

Everybody turned toward the voice. Mr. Honda was sprinting toward them with his hair flying up.

Kazuo could not remember Mr. Honda ever looking angry before. But at that moment, his face looked as scary as a demon’s. He ran up at full speed and planted himself before Masato.

“What did you just say to Minoru Kaneda?”

“I called him a Korean pig,” Masato answered without a sign of remorse. “He’s a Korean, so I called him one. I didn’t do anything wrong.”

The next moment, an unbelievable scene unfolded before Kazuo’s eyes.

Mr. Honda’s pale hand came down hard on Masato’s cheek, as if in slow motion. Mild-mannered Mr. Honda had hit a student! Everyone fell silent in shock. Even Yukichi, the ringleader of the incident, and Minoru, who had been crying, grew quiet and stared in disbelief.

“You ought to be ashamed of yourself as a human being,” Mr. Honda continued. “You’re a fifth-grader, yet you lose at sumo and have to go picking on a fourth-grader? Do you find that enjoyable? And have you no idea how shameful it is to discriminate against another person?”

The teacher seized Masato by the arm and marched him off to the office. Kazuo and the rest of his classmates, including Yukichi, remained silent, as if they were the ones being punished. They stayed that way even after they had returned to their classroom. Saying nothing, they waited quietly in their seats.

Soon Mr. Honda came in. His face was pale as he looked around at all of the students in the class. “First of all, I need to apologize. Today during lunch recess, when a fifth-grade student insulted Kaneda-kun, I grew very angry and hit that student. Using violence against other people is unacceptable under any circumstances. I was wrong to do what I did, and I would like to apologize to you.”

The teacher bowed low before the class.

“I would, however, like everyone to understand why I got upset,” Mr. Honda said, then wrote some characters on the chalkboard.

“These characters are read sabetsu, which means discrimination. This is making fun of, or looking down on, people because of the color of their skin, their nationality, or the way they look. It is a shameful practice, the one thing people should avoid doing at all costs. The reason I got upset today was because the older student made fun of Kaneda-kun’s Korean nationality. There are other students besides Kaneda-kun in this school who are nationals of North Korea or South Korea.”

Mr. Honda is talking about Hanae, Kazuo realized. When Minoru began to cry, she alone had confronted Masato. Kazuo was impressed that she had tried to take him on, even though she was a girl.

“Now why are there residents of Japan who have North Korean and South Korean nationality? They are known as zainichi, or resident, Koreans.”

Kazuo listened as Mr. Honda explained that before World War II, Korea had been colonized by the Japanese. The people in Korea were forbidden to use their native language or their real names and were put to work like servants. Later on, during the war, when the male adults of Japan were off fighting as soldiers and there was a shortage of workers in coal mines and factories, many people from Korea and China were forcibly brought to Japan and made to work like slaves, without even getting enough to eat.

“So the Koreans living in Japan had their homes and livelihoods taken from them,” Mr. Honda explained.

Kazuo listened uneasily. He had heard from his parents that during the war there were air raids almost every day, that life had been hard because food was scarce, and so on. He had been told that many people died in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and in the firebombings of Tokyo. He knew that war was very bad, bringing misery to many people.

But Mr. Honda had just said that the Japanese had ruled over Minoru and Hanae’s parents, and grandparents, and their friends, and treated them like slaves. Everything the teacher had talked about, all those terrible things, had been done by people connected with Kazuo.

That day his discomfort made him decide one thing: from then on he would be kinder to Minoru and Hanae.

Now, as he stood on the hill behind the telephone pole, listening to the labored breathing of Minoru and his father, Kazuo wondered why he had jumped out of sight so quickly. He thought it was because Minoru might feel embarrassed to be seen pushing his scrap man father’s cart. If it were Kazuo, he would feel shame, as if a dark secret had been revealed.

But Kazuo also wondered if his act might be called discrimination. Maybe Kazuo was looking down on the work that Minoru’s father did, judging it as dirty and shameful. Kazuo felt a heavy lump deep down in his chest. Minoru and his father began to move the cart forward again. Soon Kazuo could hear Minoru’s father shouting, “Scrap man, will haul!”

Kazuo knew he could still call out, “Minoru, how’s it going?” And sturdy Minoru would probably just crinkle his round face into a smile and wave back.

But that is not what Kazuo did.

The sounds of the bell on the cart’s handle and of Minoru’s father calling out, “Scrap man! Will haul!” gradually moved away through the quiet town as sunlight flooded its streets.

Kazuo, still hidden in the shadow of the telephone pole, stood as if frozen, listening intently to those two sounds.

NISHINO-KUN’S HOUSE OF BOOKS

The other friend that Kazuo made in November was Akira Nishino. Nobuo and Minoru usually called him just Akira or by the nickname Nishiyan. But Kazuo eventually started to call him Nishino out of respect.

Akira’s father was a university professor, and his mother was an elementary school teacher. Not one other student in Kazuo’s grade had a parent who was a teacher, and only a few students had a parent with a university degree. Most parents, like Kazuo’s father, had gone straight to work after finishing their compulsory education.

Akira was polite to everyone, as well as kind. But when it came to his grades in school, he definitely did not fit Kazuo’s expectations of a child of two teachers.

That was because Akira spent a lot of time absentmindedly staring out the window. When he wasn’t staring out the window, he seemed to be thinking about something completely different from what was being written on the chalkboard or explained by the teacher. When Mr. Honda pointed at him to answer a question, he would often give an answer that made no sense, making the kind teacher smile wryly. Akira seemed to have an especially hard time with math. He still made mistakes, even though he was in fourth grade now.

Still, Akira appeared to be acting a little more lively in school these days. Last year, with Mr. Tanaka, who was strict and lost his temper at the drop of a hat, Akira had gotten a scolding nearly every day. When he gave a wrong answer or made a mistake at math, Mr. Tanaka would say, “If you can’t even handle this problem, don’t you think your parents will be disappointed in you?”

And Akira would press his lips together and nod, his face the saddest in the entire world.

But one day in April, Kazuo had changed his opinion of his classmate.

During science, Mr. Honda had been talking about pistils and stamens in flowers, explaining that the reason flowers bloom on plants and trees is to produce seeds and fruit. Then he asked a question of Akira, calling him by his family name.

“Nishino-kun, why is it that flowers bloom on plants and trees?”

Akira, who had been staring out the window, turned red in the face. He remained silent, crossing his long, thin arms awkwardly in front of his body.

“You must not have heard my question,” Mr. Honda said gently. “Very well, I will ask you again. Why is it that flowers bloom on plants and trees?”

Akira stared silently at the ceiling.

“How about it, did you think of something?” Mr. Honda prodded him.

“Perhaps . . . ” he said in a small voice.

“Perhaps what?”

“Perhaps flowers bloom to get attention from people and insects and animals,” Akira finally said.

Half of the students tittered. His answer was just too strange—as if plants and trees would flower for the same reason people get dressed up, to get attention.

“Everyone, please be quiet.” The teacher silenced the laughter. “So, Nishino-kun, why do you think that is?”

Akira still spoke softly. “When flowers are in bloom, people and insects and animals are attracted to their colors and smells and go over to them. That probably makes it easier for the pollen to scatter, and easier to produce seeds and fruit.”

Mr. Honda nodded vigorously several times, grinning broadly. And this time nobody laughed.

“Nishino-kun’s response was an extremely good one,” Mr. Honda said. Then he motioned for Akira to sit down. “Nishino-kun focused on the beauty and scent of flowers, and considered them within all of nature. It is exactly as Nishino-kun has explained: flowers’ beauty brings insects and animals closer, and makes the pollen on the stamens easier to scatter. This way the plants do not have to rely only on the wind to get the pollen to the pistils.”

Listening to Mr. Honda, Kazuo began wondering about Akira, who had always seemed so absent-minded and slow to find the right answer. Maybe he was more interesting than Kazuo had realized. Maybe he had even more mysterious ideas inside his head. After this, Kazuo himself began to add the suffix “-kun” to Akira’s family name as a sign of respect.

After Nishino-kun and Minoru ended up in the same group as Kazuo, the three of them often walked home together. Nobuo, and sometimes Yasuo, joined them, making them a group of five—the J-Boys. The boys said if they ever had a rock band, that was what they’d call themselves. In their own language they were , but to Americans, they were “Japanese boys.” That’s what Nishino-kun had said, anyway, and the name just stuck.

On the days when the weather was fine, they always went to the empty lot. Nobuo and Kazuo had not yet given up on their Bob Hayes program. As soon as they got to the lot, they began talking back and forth about Bob Hayes. Then they practiced starting low to the ground and charging into a sprint as they took off running.

Nishino-kun and Minoru sat on the wilted grass and watched them. Neither had ever heard of the great sprinter Bob Hayes from the Tokyo Olympics. Plus, Nishino-kun had absolutely no interest in sports, while Minoru knew the names of sumo wrestlers but nothing about the other sports.

Today, after Kazuo and Nobuo grew tired of their efforts, the four friends sat talking.

“What do you want to be in the future?” Nobuo asked suddenly. He was sprawled on the ground, his chin resting in his hand, which was propped up by one elbow.

“A sumo wrestler, of course.” Minoru jumped up and got into the squat that wrestlers assume before a match, spreading his arms out wide. “I’m going to reach the rank, live in a huge house, and eat good food every day until I’m bursting.”

Nobuo grinned. “You’re an eater, aren’t you, Minoru!”

Minoru laughed self-consciously.

“I’m going to be a runner,” Nobuo said, brimming with confidence. “I’m going to compete at the Olympics and win the gold medal. I’ll run the hundred meters in one burst, just like Bob Hayes. But my time is going to be nine seconds flat, a new world record. How about that—impressive, huh?”

Watching Nobuo as he flared his nostrils and spoke with gusto, Kazuo felt that one day his friend just might make his dream come true. Nobuo had been growing a lot recently and was now quite tall.

“And what do you want to be, Nishiyan?” Minoru asked. Nishino-kun had been listening to the other two with a quiet smile.

“I bet you’ll be a college professor like your father,” Nobuo interrupted before Nishino-kun could answer. “With all those books, it would be a waste if you didn’t become one!”

Kazuo suddenly pictured the inside of Nishino-kun’s house behind the shopping area. Two weeks ago, they had all gone there to play, taking Yasuo with them. Because Nishino-kun’s parents were both educators, Kazuo had expected to see a white house with a triangular roof, like the houses in American TV shows. He’d imagined carpets on the floor, and chairs and tables, and the family drinking black tea or coffee.

But when Nishino-kun said, “This is it,” and pointed to his house, Kazuo saw instead an aging wooden structure that looked exactly like every other house in West Ito. The exterior walls were covered in cedar boards that had weathered to a dark brown. The roof was a traditional black tile roof, and the front door was no different from the door to Kazuo’s company housing unit: a sliding door with frosted glass windows. It was an extremely ordinary house.

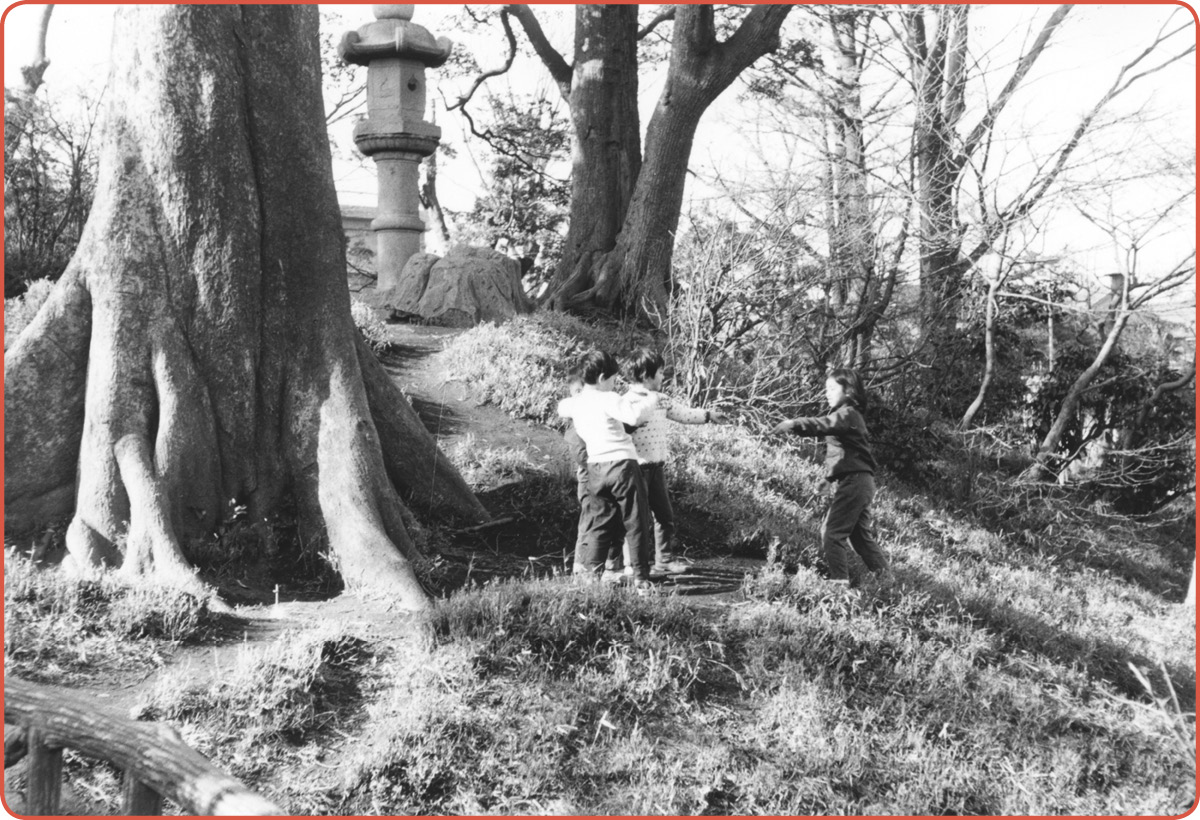

Boys playing near a huge tree in a city park.

Following Nishino-kun, the boys passed the Nishino Residence nameplate on the front gatepost and headed to the door. To the right of the path was a small garden.

“Hey, Nishino-kun, you could have a dog here!” Yasuo told him when he spotted the garden.

“Yasuo, is that the only thing you ever think about?” Kazuo said, and everybody laughed at his exasperated tone.

“Actually, I wish I could have a dog,” Nishino-kun said.

“You should get one!” Yasuo agreed, excited.

But Nishino-kun smiled sadly. “My father won’t let me. He says that having a dog would ruin the garden.”

None of the boys knew why having a dog would ruin the garden. But if Nishino-kun’s university-professor father said it would, they had to believe it.

Nishino-kun used a key to open the old door to the entryway. It slid to the side with a clatter, like a cart traveling through gravel. But when the four boys saw what appeared beyond it, their mouths dropped open.

Nishino-kun’s house was crammed with books.

The was typically a place where people sat or bent down to put their shoes on or take them off. At Nishino-kun’s house, however, the books took up so much space that there was nowhere to sit down. Tall stacks of books were everywhere, lining both sides of the hallway leading into the interior of the house.

“Go on in.” At Nishino-kun’s urging, the boys ventured further inside, where the air smelled musty, like old paper. Yasuo clung to the bottom of Kazuo’s sweater, looking as frightened as if he had lost his way in a haunted mansion.

“These sure are huge piles of books,” Kazuo said to Nishino-kun. He tried to sound nonchalant as he gaped at all of the stacks, which seemed to have them surrounded. “Are they all your father’s?”

“Yeah, they’re his,” Nishino-kun answered.

Kazuo noticed that more than half of the books were in foreign languages.

“Why don’t we have some juice or something?” Nishino-kun suggested. He led them into the living room and brought some juice powder, cups, and a kettle of water from the kitchen. Kazuo and the others continued to look about uneasily, not touching the juice that Nishino-kun prepared in front of them.

Nobuo’s eyes were fixed on some sliding doors at the back of the room. A pine tree was painted on them. “Is there a room on the other side of those doors, too?”

“Yeah, that’s my dad’s study. Would you like to see it?” Nishino-kun stood up and opened the doors.

Kazuo saw yet another room overflowing with books. It did not look like it was even used by humans. With just a tiny bit of afternoon sunlight streaming in through an opening in the curtains, it looked more like something from a science-fiction movie.

All the walls of the six-mat room had large bookcases placed against them. Books that did not fit into the bookcases were piled into towering stacks on the floor. Kazuo thought they looked like skyscrapers built by aliens. He could even picture a creature with an oversized head and detached eyeballs sitting at the desk in the middle of the room and ruling over the alien city.

And so, two weeks later, as the boys sat in the empty lot talking about their futures, Nobuo was obviously remembering all the books in Nishino-kun’s house, too. But when he asked Nishino-kun if he were going to be a college professor, Nishino-kun shook his head. “That would be impossible. I’m not very smart, you know.” He wrapped his long, skinny arms around his legs and looked away.

“You’re smart,” Kazuo spoke up.

“Yeah,” Nobuo chimed in. “If you don’t want to be a college professor, then what do you want to do?”

Nishino-kun stayed silent. He just kept staring off at the wilted, brown grass.

Kazuo exchanged glances with the others. He couldn’t help feeling annoyed with Nishino-kun. His family was well off, at least compared to the rest of them. Both of his parents were teachers, and he had a ton of books in his household. He ought to be able to do anything he wanted when he got older.

“Akira!” someone said sharply.

Kazuo turned around. A thin man wearing a gray suit and glasses was coming toward them.

“Otohsan!” Nishino-kun scrambled to his feet.

Nishino-kun’s father approached the boys with deliberate strides. “These must be your friends.” He held a bulging briefcase, and his forehead was furrowed as he glanced at Kazuo and the others.

“Yes,” Nishino-kun answered in a small voice.

“Is your homework done yet?”

“No, not yet.” Nishino-kun hung his head.

“Well then, instead of loitering in a place like this, I want you to go straight home and study. Do I make myself clear?” Nishino-kun’s father spoke in a low, stern voice.

Nishino-kun nodded, then picked up his backpack.

“I’ll see you tomorrow, everyone,” he muttered. He hunched his shoulders as he followed his father out of the lot.

“He’s heading home to that house of his,” Minoru murmured.

Kazuo knew exactly what Minoru was saying. In that house of his, Nishino-kun probably had to study under the stern eye of his father. Kazuo himself studied while being nagged by his mother. But that was in the living room with the TV on, and plenty of ways to escape her instructions. Nishino-kun’s house, which seemed to exist for the sole purpose of storing books, probably didn’t have any escape routes.

A chilly wind had begun to blow though the empty lot. Without anybody saying much of anything, Kazuo, Nobuo, and Minoru got up and put on their backpacks.

“Well, see you,” Minoru said.

“Yeah, see you tomorrow,” Nobuo answered.

“Bye.” Kazuo waved and started for home. As he walked, he thought again about Nishino-kun and how he’d refused to say anything about his future plans. Why had he acted so stubborn? Kazuo wondered. Then he remembered how Nishino-kun acted in class, all dreamy with his unusual way of thinking that Mr. Honda seemed to admire. Nishino-kun was different, that was for sure. But maybe like the other boys, he did dream about his future. It was just that he had trouble expressing that dream in words because of the mountains of books in his house, or because of that low, stern voice that told him to “go straight home and study.”

Kazuo smiled when he remembered what he himself had said about what he wanted to be when he grew up. He hadn’t answered with his father’s words: “Kazuo will enter a national university, get a Ph.D., and work at a top company!” Instead he’d said the first thing that had popped into his head.

“I think I’ll be the captain of a ship that goes to foreign countries.”

“That’s cool,” Minoru had said. The others had grinned and nodded.

Kazuo was nearly home. The sun had set and the sky was nearly black now.

Being the captain of a ship does sound cool, Kazuo thought. He wondered if he’d really do it. He wondered what the future held for any of the J-Boys.