Kazuo’s Typical Tokyo Saturday

Every once in a while, Kazuo liked to walk around his part of Tokyo by himself. He would get in the mood to ramble without Yasuo or Nobuo along, and so he would head off without a destination.

He often did this on afternoons, after school had adjourned in the morning and he, his mother, and Yasuo had eaten lunch together. He would leave the house with the excuse that he was “going to play with Nobuo.”

He loved Saturday afternoons. Everybody did, of course, because work and school had ended and Sunday was a holiday. To Kazuo, time seemed to pass more slowly. The whole town appeared to take a collective deep breath and sprawl out on the floor, forgetting the week’s troubles. Walking around Tokyo as it exhaled this way was something Kazuo deeply enjoyed. Sometimes, he crossed the Haneto River, with its stench of factory wastewater that made him want to plug his nose, and headed toward Hara. Other times, he walked past the big houses on the hill in District 4, where he had seen Minoru and his father hauling their scrap cart, and ventured as far as the next ward. Or he went through the West Ito shopping area, where Nobuo’s house was, and walked the maze of narrow alleyways behind it, which was where Nishino-kun lived.

He had recently begun to realize that the streets of were changing. They had been changing, it seemed, ever since the Tokyo Olympics the year before last.

Dirt roads that had filled with puddles when it rained had been paved over, and old wooden houses had been knocked down and replaced with new stucco homes. , whose red iron tip Kazuo had once been able to see from the District 4 hill, had become invisible, probably because so many new buildings now blocked it from view. Just as Father’s older brother Yoshio had said when he visited their family before New Year’s, construction had been going on all over Tokyo before the Olympics. Huge stadiums had been built, highways had been routed through the center of the city, and the fastest bullet train in the world had begun regular service between Tokyo and Osaka.

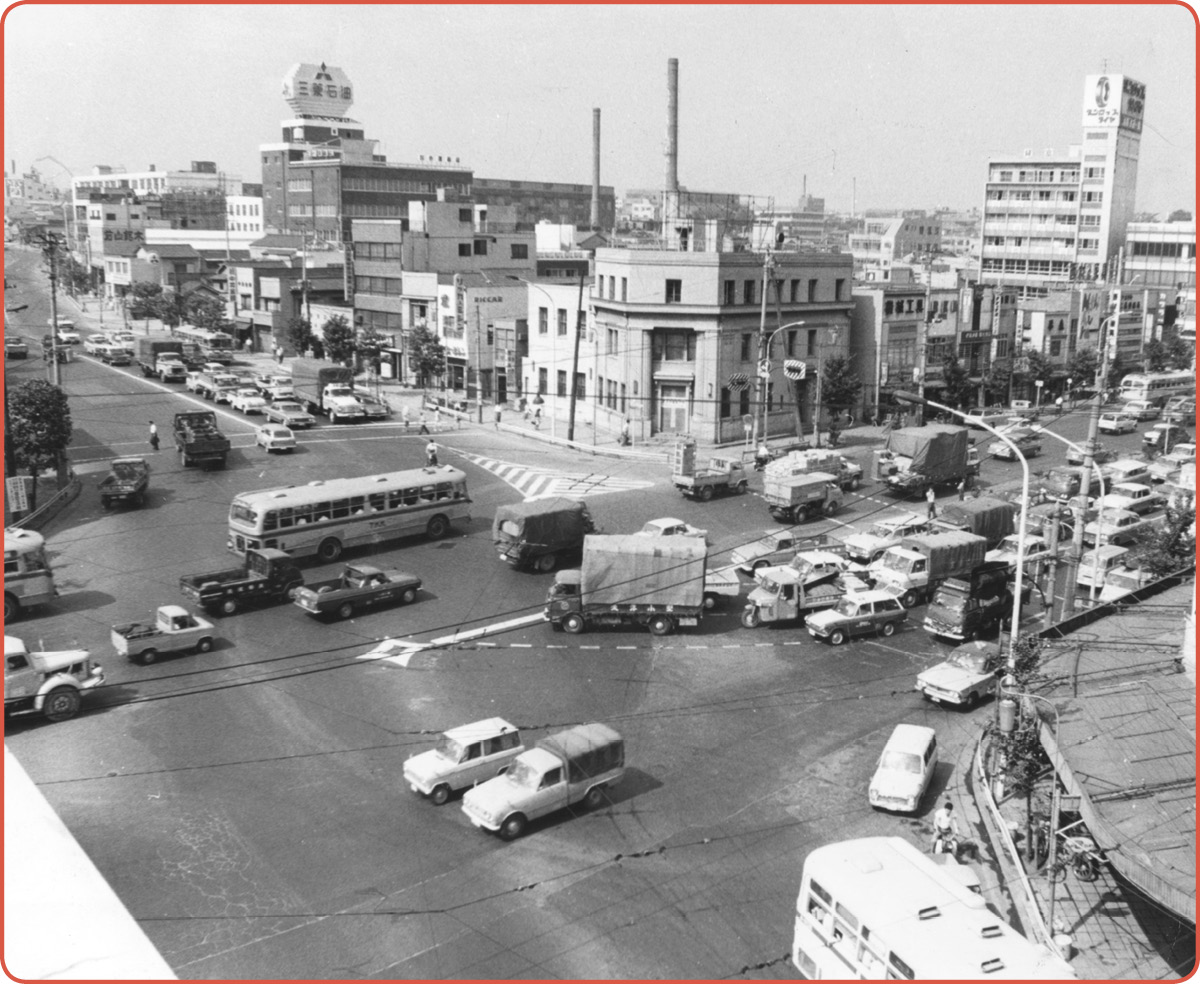

Then again, the construction of new buildings was not the only reason Tokyo Tower was harder to see. Kazuo had learned on the TV news that exhaust fumes from cars were dirtying the air. He himself had observed that the number of cars on the road was increasing at a very high rate.

He used to be able to cross National Highway One, which intersected the south end of the West Ito shopping area, even with no pedestrian crossing signal. But now there were so many cars that walking across the highway without a signal was impossible.

He did not feel that all this change was bad. Car fumes dirtying the air was certainly a problem, but the tall buildings and automobiles showed that Japan was becoming wealthier. At school, the students still had to drink that awful miruku, but that was a different story.

A busy intersection in Shinagawa Ward.

One Saturday, Kazuo finished lunch and told his mother that he was going to the lot to play. Then he began to walk in the direction of the West Ito shopping area, the January wind gusting around him. There was still plenty of time before the late-afternoon rush, when the area would bustle with shoppers. Only a few people passed him on the street now.

He reached the center of the shopping area and saw Takahashi Meats, the shop owned by Nobuo’s family. He could smell the delicious aroma of croquettes and see Nobuo’s mother frying them at the front of the store. Nobuo was nowhere to be seen. Maybe he was in the back mashing boiled potatoes for the croquettes. Or maybe he was upstairs where the family lived, shirking his chores and getting lost in a comic book.

Whatever the case, Kazuo did not want to be noticed, so he crossed the street and walked quickly past the Takahashis’ shop. He glanced back. Still busy frying the croquettes, Nobuo’s mother did not seem to have noticed him. He exhaled softly and headed for the train station, feeling a little guilty.

Next to the station was Chujiya, the bar where his father often stopped on his way home. Smoke would be billowing from the yakitori chicken barbecue by late afternoon, but right now the doors were closed. Two buildings down, at the hall, he could hear music and the constant clicking of metal balls.

Until last year, the pachinko hall had been a cinema called the Ito Theater. It had shown movies for children during the school holidays, and it was here that the children of West Ito had watched, on the edge of their seats, as took on and and and wreaked havoc in the cities of Japan.

But in the spring of the previous year, the Ito Theater had suddenly closed. That had come as a big shock to Kazuo. Father said it was because everybody had gotten a TV set and stopped going out to the theaters.

“Used to be we didn’t have any TV at all, so movies and plays were the best entertainment there was. Week in and week out, people would look up which movie stars were in which movies and then go out to see them.”

Father spoke while staring at the TV’s tiny black-andwhite screen. A samurai was fending off his attackers.

“Even the tiniest towns had a movie theater or two,” he continued. “So you could see a movie close to home, and it didn’t cost very much. But now there’s a TV set in every house. Nobody bothers going to the theater anymore, unless there’s a movie they really want to see. It’s no wonder the little local cinemas are hurting for business.

“TV has its good points and its bad points,” he added, “but there’s nothing you can do about the times changing.”

Now, listening to the clicking of metal balls through the glass in the pachinko hall’s front door, Kazuo found himself remembering how a man used to perform on Tuesdays in a side street near company housing.

Those kamishibai performances, in which the man told stories while showing colorfully illustrated panels in a wooden stage, were one of Kazuo’s greatest delights.

The kamishibai man always came at three o’clock on Tuesdays, carrying illustrated kamishibai cards and cheap sweets in a big wooden box on the back of his black bicycle. When he arrived, he would bang his wooden clappers together to summon the children. Then the children would pay five yen apiece for wafer-thin rice crackers spread with just the tiniest bit of apricot jam, syrup, or savory sauce.

After a group of children had bought their sweets, the man would raise the top portion of his wooden box to create a stage. He would then slide his illustrated cards into and out of the stage as he performed a kamishibai. Sometimes, he told adventure stories about the young ninja or the —“a friend of justice who fights evil.” Other times, the children heard about a young girl in search of her long-lost mother, or about the funny Happy-Go-Lucky Boy, or they enjoyed quizzes. The kamishibai man had different voices for different characters, and the children would be completely drawn into the world of the story that unfolded before them. The performances probably lasted only ten or fifteen minutes, but to Kazuo, they were as thrilling as a one- or two-hour movie.

Around the time he started school, however, the kamishibai man had stopped coming. That was just before Kazuo’s family got a TV set, on which American shows such as Father Knows Best, Popeye the Sailor, and Tom and Jerry, and Japanese-made programs such as Moonlight Mask were being broadcast every day. These programs were not necessarily more interesting than kamishibai, but it was easier to stay home and watch the performances on the black-and-white screen.

After he left the pachinko parlor, Kazuo walked along a road that followed the train tracks. Right next to him, a train of four cars sped off into the distance with its caution whistle blowing. The fact that Tokyo was quickly changing, and that the movie theater and kamishibai man had disappeared, was not something he could blame entirely on the Olympics or TV, he realized. He himself, and Nobuo and Yasuo, and Mother and Father, and the many people living around them, had begun to prefer the new Tokyo over the old. He wondered if this was good or bad.

And if he knew one thing for sure, it was that his city would continue to change.