The appointment of William Dowdeswell as governor of the Bahama Islands in late 1797 more or less made it official: Dunmore’s career in the empire was over. His would not be a restful retirement. Between the saga of Lady Augusta’s marriage and the family’s finances, sources of anxiety were legion and every day a struggle.

George III was determined that his son never see Augusta again. But despite years of Crown-mandated separation, the prince remained committed to his young family. In a letter to Augusta in the spring of 1796, Augustus Frederick recalled the consummation of their marriage with rapture: “To this day my treasure do we owe the origin of our dear little boy…. This day three years ago was the first full Pleasure I enjoyed of my Wife.” After hearing exaggerated reports of her husband’s failing health in 1799, Augusta travelled under an assumed name to see him in Berlin, where the couple spent several happy weeks together. During that period, the prince asked Dunmore, then in London, to forward their marriage certificate to Germany. When Augusta decided to return to England, her husband followed. For much of 1800, they lived together at 40 Lower Grosvenor Street with their son, like the family they longed to be.1

These were tense, uncertain times for Dunmore. Although in good health, his financial woes continued. If he saw Augusta’s connection to the House of Hanover as a potential source of salvation, he knew enough not to rely on it alone. In 1800, he and John Miller were in London trying to convince the ministry to reimburse them for their investments with William Bowles. The ultimate failure of this effort coincided with a painful turn of events for Augusta. When the prince took his usual leave of England in the winter of 1800–1801, he did not know that she was pregnant with their second child, a daughter named Augusta Emma, the future Lady Truro. Jane Austen, whose brother shared the voyage back to England with the prince in 1801, reported that he “talks of Lady Augusta as his wife, and seems much attached to her.” Malicious gossip, however, gave rise to rumors that Lady Augusta’s pregnancy had resulted from an indiscretion. Possibly influenced by these stories, the prince abruptly ended the relationship in December 1801. Only days later, he was created Duke of Sussex. The news came as a shock to Augusta. In search of an explanation, she traveled to Lisbon in the spring of 1802, only to be turned away from the prince’s residence, an insult that she felt made her “the sport of his mistress & dependents.” She defended her honor and sought to shame her detractors in an affecting letter to Augustus’s older brother, the Prince of Wales, but the damage was done. She was left to provide for two children with no regular income. Augustus himself was having a hard time securing his own allowance from the Treasury at this time, but unlike Augusta he never had to struggle to pay for his bread.2

Outraged by his daughter’s treatment, Dunmore secured a conference with the king in October 1803. It was the last time the two men met. “Our Father has just returned from his Audience with the King in a most famous rage,” Jack Murray informed one of his brothers. The story, as retold by Jack, provides a rare glimpse of Dunmore both in old age and through the eyes of his children:

He informed us that before he went to the King, he was urged by Mr Addington [the prime minister] to be as moderate as possible on the subject he was about to bring under His Majesty’s consideration—as it was one to which he was most particularly alive. Our Father then went on to detail to us that having laid before the King the marriage of his daughter Augusta with his Son at Rome—he then proceeded to expatiate on the treatment she had experienced at his hands, by leaving her penniless and subject to all the misery of being arrested and of having her house daily beset by Creditors asking and demanding payment of her for things which had been furnished while her husband was living with her and many of which he had taken with him to Lisbon, leaving her without a shilling to provide for herself or his family during his absence or to pay the debts so contracted by him before his departure, all of which was quietly [heard] by the King until our Father went on to enlarge also on his [Augustus’s] unfeeling conduct to his children in leaving them in such a state of destitution, on which the King broke out in a rage, calling them “Bastards! Bastards!” To which our Father replied by observing “Yes, Sire, just such Bastards as your [children] are!” On his stating which the King, he said, became as red as a Turkey cock, and going up to him repeated “What, what, what’s that you say, My Lord?” “I say, Sir, that my daughter was legally married to your son and that her children are just such Bastards as Your Majesty’s are”—on hearing which the King stared at him—as if in a violent passion and then without uttering a word retired into another room and thus terminated the interview, while our Father, having finished his narrative, observed to us God damn him—It was as much as I could do to refrain from attempting to knock him down—when he called them Bastards! And really the Old Cock [Dunmore], tho’ in the seventy second year of his age, looked at the moment as if he could have done [it] without much difficulty and which, if I am to judge from the grip which he can yet give with [his] paw, he is yet equal to have done.3

However accurate in the details, this account indicates that Dunmore was as proud and passionate as ever in 1803. His fiery temperament had survived the disappointment of virtually all his dreams, even if only in self-aggrandizing stories told to his children. Two years later, Jack Murray died aboard a British ship in the West Indies during the blockade of Curacao. The seventy-five-year-old father who survived him remained formidable still.

Augusta’s situation got worse before it got better. Since many of her obligations, which ultimately exceeded £25,000, had been incurred by the prince, she filed a suit against him in the Court of Chancery. With the decision pending, she was nearly arrested for her outstanding debts, escaping imprisonment only through the eleventh-hour intervention of a friend.4 Finally, in 1806, she reached an accommodation with the royal family, according to which Augustus and the Treasury combined to pay her bills in full (or nearly). She was also granted an annual pension of £4,000 as well as additional funds for the upbringing of the children. In exchange, she had to drop the lawsuit and forever relinquish her ties to the prince. This meant forfeiting the title Duchess of Sussex, which in her pride and bitterness she had taken to using. Thereafter, she was to be known as Lady Augusta De Ameland, a name from her parents’ joint lineage. These were merely public concessions. In private, she continued to encourage her children to view themselves as unequivocally royal. The first cousin of Queen Victoria, Augustus D’Esté was still pursuing legitimacy through the courts as late as 1831.5

Lord and Lady Dunmore spent their last years near the ocean in Kent. A popular destination for those seeking salubrious air, the seaside town of Ramsgate was also home to Augusta and her daughter (young Augustus spent most of his time away at school). As the beneficiary of a substantial royal pension, Augusta helped to support and care for her father and mother in their dotage. Moving the elderly earl one day, she sustained a back injury that bothered her for the rest of her life. With a degree of financial security, however, these were happy times, at least for Augusta, for whom “dear Ramsgate” always held special significance.6

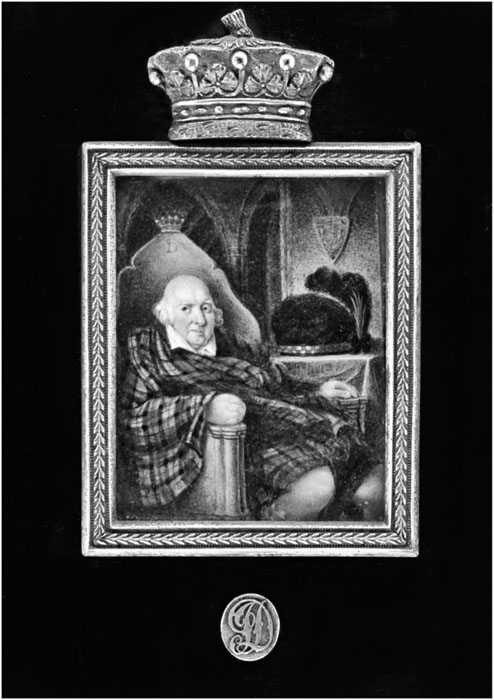

FIGURE 12. This miniature portrait of Dunmore, painted shortly before his death by an unknown artist, bears an inscription on the back that reads, “D[utche]ss of Sussex’s Picture of her Beloved Father John Murray Earl of Dunmore Taken Febry 1809.” A nearly identical portrait, evidently by a different painter, can be found in the same collection. (The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase)

On 25 February 1809, Dunmore died. He was seventy-eight years old and suffering from what a contemporary described as “decay.”7 Shortly before his death, Augusta commissioned a miniature portrait of him, a tribute to her “Beloved father,” whom she called “Pappy.” At first glance, the picture seems a world apart from the youthful, heroic portrait painted by Joshua Reynolds more than a half century earlier. Alongside the larger Romantic image, the miniature is striking in its realism. A frail Dunmore slumps in his seat. He is bald except for patches of long white hair that cover his ears. As in 1765, he wears tartan. A Scots bonnet rests on a table beside him. His expression bears the hint of a smile, but his eyes are tired. In the foreground, his right hand forms a fist on the arm of the chair, as if punctuating some unheeded insistence.8