The political and cultural beginnings in the five classical societies of Persia, Greece, India, Rome, and China laid the foundations for future development. Classical Greek and Indian societies created the foundations for the development of future decentralized governments, while classical Roman and Chinese societies created the blueprint for later centralized states.

Ancient Persia was centered in present-day Iran but grew to include Egypt, Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and Assyria. People first migrated to this area around 1000 B.C.E. and established a number of small kingdoms.

Around 550 B.C.E., the Persian king Cyrus II began to conquer neighboring kingdoms. By 539 B.C.E., he controlled an empire that extended 2,000 miles from the Indus River to Anatolia (present-day Turkey). Cyruss legacy is the method of his rule. Unlike most conquerors of this period, Cyrus honored local customs and religions of conquered peoples. He ended the Babylonian captivity of the Jews, allowing them to return to Jerusalem in 538 B.C.E. and rebuild their holiest temple; Cyrus would be mentioned 23 times in the Bible for this act, and described with the highest praise.

The Persian emperor Darius I, whose 36-year rule began in 522 B.C.E., is noted for his administrative genius. He divided the empire into 20 provinces, each of which closely resembled the homelands of the different peoples who lived in the empire. Each province was ruled by a satrap, who allowed the people under his jurisdiction to practice their own religion, speak their own language, and follow their own laws. Satraps collected tribute taxes, maintained roads, and performed other administrative duties.

Darius used other tools to maintain his empire, which also brought economic benefits. The Persians created an excellent road system that included the 1,677-mile Royal Road, which facilitated communication and trade within the empire. Darius also manufactured metal coins of standard value that were used throughout the empire. This network of roads and standardized coins stimulated trade.

Society was divided into three categories: warriors (the dominant element of society), priests (called Magi), and peasant farmers. Although family organization was patriarchal, women in the Persian elite were politically influential, possessed substantial property, and traveled.

Greeces political identity revolved around the concept of the polis (city-state). Greeces mountainous geography helped in the development of this decentralized political structure. Although different city-states emerged independently, they still shared a common language and somewhat similar cultural practices. A few city-states functioned as monarchies, but most were based on some form of collaborative rule.

It is worth noting that Athens did not start out as a democracy. Rather, political tyrants were overthrown in favor of an oligarchy, and then ultimately, a democracy. It was under Pericles that democracy was established. Over time, population pressures led to the establishment of colonies along the Mediterranean Sea, yet a centralized state was not created. These colonies relied on their own resources and took their own course. They did, however, facilitate trade throughout the region.

Greek cities in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) resented what they viewed as the oppressive rule of the Persian Empire and revolted, starting the Persian War (499–449 B.C.E.). Athenians, too, sent their own troops in support. In two separate wars occurring a decade apart, the Persians attacked the Greek mainland. During the first war, the important victory at Marathon by the Athenians led to the Golden Age of Athens. During the second war, the Athenian-led naval victory at Salamis and the Spartan-led army victory at Plataea stopped the Persian attempts to conquer the Greek city-states. The Greeks also developed a new kind of warfare, waged by hoplites—citizen-soldiers who were heavily armored, carried spears and shields, and fought in a phalanx formation.

The alliance of the Greeks against the Persians led to the formation of the Delian League, of which Athens served as the leader. However, the heavy-handed leadership of Athens spurred resentment within the league. This unrest led to the Peloponnesian War (431–404 B.C.E.). Sparta and Athens led the two opposing camps. Though Sparta was victorious, the conflict weakened Greece, leaving it vulnerable to domination by a stronger power—Macedonia, a frontier state north of the Greek peninsula.

King Philip II of Macedonia, who ruled from 359–336 B.C.E., consolidated control of his kingdom and moved into Greece, and by 338 B.C.E., the region was under his control. His next goal was to conquer Persia, but that job would be left to his son, Alexander the Great.

Alexander, a skilled military commander and strategist, successfully conquered Persia by 330 B.C.E. and went on to conquer most of the northwestern regions of the Indian subcontinent. At that point his troops refused to go any further. By 323 B.C.E., at the age of 33, Alexander the Great was dead. What he left behind was the creation of a Hellenistic Empire and Era. The empire was divided among three of his generals who were the namesakes for these areas: Antigonid (Greece and Macedonia), Ptolemaic (Egypt), and Seleucid (Persia).

The Greek world relied heavily on trade as the cornerstone of its economy. The Mediterranean Sea linked its communities through trade and created a larger Greek community. During the Hellenistic Era, caravan trade flourished from Persia to the West, and sea lanes were widely traveled throughout the Mediterranean Sea, Persian Gulf, and Arabian Sea. This trade created a cosmopolitan culture.

Overall, Greece was a patriarchal society with fairly strict social divisions. Women were under the authority of their fathers, husbands, and then, sons. Most women owned no land and they often wore veils in public. Their one public position could be that of a priestess of a religious cult. Literacy, however, was common among upper-class Greek women, and Spartan women took part in athletic competitions.

The two most famous city-states were Athens and Sparta. Athens used democratic principles to negotiate order, while Sparta used military strength to impose order. Athens' government was a direct democracy that relied on its small size and the intense participation of its citizens. However, those citizens were restricted to free adult males, and excluded women, foreigners, and slaves. The Spartans, on the other hand, lived life with no luxuries. Distinction was earned through discipline and military talent. Boys began their rigorous military training at age seven, and girls received physical education to promote the birth of strong children.

Slaves comprised about 30 percent of Greek society and were acquired because they had debts they could not repay, were prisoners of war, or were traded. The treatment of slaves varied widely, depending of their assigned task and the temperament of the owner.

The Hellenistic Era greatly contributed to cultural diffusion. It was particularly facilitated by the conquests of Alexander the Great. Culturally, the Greeks stressed a central importance on human life and a growing appreciation of human beauty. This is seen through Greek religion, philosophy, art, architecture, literature, athletics, and science.

Polytheistic, the Greeks believed that their gods were personifications of nature. Each city-state had its own patron god or goddess for whom rituals were performed. One of the greatest legacies of classical Greek civilization is philosophy. The great philosopher Socrates, who posed questions and encouraged reflection, is credited as saying, The unexamined life is not worth living. His student Plato wrote The Republic, in which he described his ideal state ruled by a philosopher king. Platos student Aristotle wrote on biology, physics, astronomy, politics, and ethics. Aristotle is considered the father of logic; his system of deductive reasoning was an important element in the development of political systems, scientific advancements, and religion up to the modern era.

In literature, the great epic poems attributed to Homer, the Iliad and the Odyssey, convey the value of the hero in Greek culture. In architecture, the Greeks built temples using pillars or columns, and they developed a realistic approach to human sculpture. The Olympic games were held regularly to demonstrate athletic excellence. The Greeks also made great strides in anatomy, astronomy, and math including the medical writings of Galen and the mathematics of Archimedes, Pythagoras, and Euclid. Greek drama also flourished in its comedies and tragedies, with notable playwrights such as Euripides. Lastly, the Greek writer, Herodotus, is credited as being the father of modern history.

Following the invasions of the Aryans, by the sixth century B.C.E., India developed into small regional kingdoms that often fought each other. Though there were periods of centralized rule, the subcontinent remained decentralized through most of its early history.

One significant example of centralized rule was that of the Mauryan Empire. In the 320s B.C.E., Chandragupta Maurya made his move to fill the power vacuum left after Alexander of Macedonia (Alexander the Great) withdrew from the region. Maurya successfully dominated the area and set up a bureaucratic administrative system to rule his empire.

His grandson, Ashoka, continued his grandfathers conquering ways until the bloody campaign to conquer Kalinga. This bloodbath convinced Ashoka to stop using a conquering approach and instead rule by moral example. He used his Rock Edicts (announcements carved into cliffs and in caves) to get his message out to the people. During his reign, Ashoka set up a tightly-organized bureaucracy that collected taxes and was made up of officials, accountants, and soldiers. He built roads, hospitals, and rest houses, and helped facilitate trade. After Ashokas death, the Mauryan Empire declined and India returned to a land of large regional kingdoms; however, order, stability, and a prosperous trade were maintained.

It was not until 320 C.E. that India would again be united under a centralized rule. Chandra Gupta established the Gupta empire and conquered many of the regional kingdoms. The south, however, remained outside his control. Instead of setting up an organized bureaucracy, the Gupta left the local government and administration in power. The Gupta empire is an example of a theater-state: a political structure acquiring its prestige and power by developing attractive cultural, public works. Under the Gupta, Hinduism emerged as the primary religion of Indian culture, while Buddhism mostly disappeared from the Indian subcontinent. Their rule continued until the invasion of the Huns severely weakened the empire and India subsequently returned to regional rule.

Indias economy benefited from the expansion of agriculture and the increase in trade throughout the classical period. Ashoka encouraged agricultural development through irrigation and encouraged trade by building roads, wells, and inns along those roads. Agricultural surplus led to an increase in the number of towns; these towns maintained marketplaces and encouraged trade. Long-distance trade increased with China, Southeast Asia, and the Mediterranean basin.

Like Greece, India developed into a patriarchal society with a strict social structure. Women were forbidden from reading the sacred prayers (the Vedas), and under Hindu law, they were legally subject to the supervision of their fathers, husbands, and then sons. In order to marry well, a womans family needed a large dowry. Women were not allowed to inherit property, and a widow was not permitted to remarry. If their husbands passed away, widows were expected to burn themselves at their husbands funeral pyre in a ritual known as sati.

The Brahmins and the caste system dominated the social structure. Caste—something that could not be changed—determined ones job, diet, and marriage. These restrictions were reinforced by the ruling class. As the Brahmins became more powerful, especially during the rule of the Guptas, caste distinctions grew more prominent.

During this period, Indias culture thrived, including its advancements in the arts, math, and science. The Mauryan emperor Ashoka became a devout Buddhist around 260 B.C.E. after the battle at Kalinga; he changed the way he ruled his empire. He rewarded Buddhists with land and encouraged their spread by building monasteries and stupas (mound-like structures that contained Buddhist relics and served as places of worship). He even sent out missionaries, who facilitated the spread of Buddhism to Central Asia, East Asia, and Southeast Asia. Still, Hinduism gradually eclipsed the influence of Buddhism. The Guptas gave land grants to Brahmins, promoted Hindu values through education, and built great temples in urban centers.

Unlike Greek art, Indian art during this time stressed symbolism rather than accurate representation. Science and math, such as geometry and algebra, flourished. The circumference of the Earth and the value of pi were calculated. Additionally, the concept of zero, the decimal system, and the base 10 number system we use today were developed.

Chinas political development during this time period laid the foundation for what would endure over two millennia. It began during a period referred to as the Warring States period (403–221 B.C.E.). During this time of turmoil and warfare, three important philosophies emerged to address the problems of the day and attempt to end the fighting: Confucianism, Daoism, and Legalism. These three philosophies were part of a larger intellectual flowering known as the Hundred Schools of Thought. Legalism offered the firmest solution to Chinas problems, preaching a practical and ruthless approach to state rule. The foundation of a states strength, it proposed, was in its agricultural production and its military, and strict laws and punishments were required to maintain order.

Chinas first emperor, Qin Shi Huang, believed Legalist ideas might be the solution to the countrys problems. In 221 B.C.E., the emperor ended the Era of Warring States and started Chinas tradition of centralized rule. The Qin dynasty created a centralized bureaucracy and divided the land into administrative provinces. For protection, he sponsored the building of defensive walls, which were the predecessor to Chinas Great Wall. Laws, currencies, weights, measures, and the Chinese script were standardized. As Emperor Qin did not approve of Confucianism, he had Confucian books burnt. Many books of history, poetry, and philosophy were also burned to stifle dissent and to unify political thought. He also had 460 scholars buried alive.

Emperor Qin ruled only 14 years, but he established the precedent for centralized rule in China, which would last for the next 2,000 years. When the emperor died in 207 B.C.E., revolts broke out and a new dynasty—the Han—was established. In 1974 C.E., a vast mausoleum built for Emperor Qin was unearthed, including a large army of terracotta soldiers.

The Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.–220 C.E.) lasted much longer than the Qin dynasty and its emperors learned from the Qins mistakes. The Han used what worked—such as centralized rule and a strong bureaucracy—but lessened the stricter aspects of the Legalist rule. As in the Zhou dynasty, the Han emperors used the Mandate of Heaven to justify their rule. It wasnt until the Yellow Turban Rebellion, a peasant revolt that lasted from 184 to 205 C.E., that the Han dynasty began to seriously decline.

The most prominent Han emperor, Wu (141–87 B.C.E.), built roads and canals, and established an imperial university with Confucianism as the basis for the curriculum. The university prepared students for civil service exams, which became the entry test for government jobs. Though in theory any young man could take the exams, bureaucratic appointments were made by the recommendation of existing officials. This allowed the landed gentry to promote their sons and entrench their own interests. The Han emperors still exerted absolute control, applying Confucian ideas on rigid, family structure to their authority over the empire. During the Han dynasty, a foreign policy of expansion was pursued, and Korea, northern Vietnam, and portions of Central Asia came under its control.

Chinas economy was based on agriculture, and it flourished during this period with increases in long-distance trade. Iron metallurgy was introduced during the Warring States period, which led to an increase in agriculture. That, in turn, allowed for an increase in trade and in the military strength of the empire. With the military expansion of the Han, peace and order allowed overland trade to increase. It was during the Han dynasty that the trade route known as the Silk Road began to flourish. The route consisted of a series of roads that connected the Han Empire with Central Asia, India, and the Roman Empire through trade.

The Han also followed a tributary system of trade. Officially, the policy stated the Han did not need to trade with their inferior neighbors, so instead, they demanded tribute from neighboring groups. These neighboring groups would visit the court, bringing tribute, and the Chinese would give trade goods in return. In addition, the Han often sent gifts to nomad groups so as to prevent any possible invasion.

China, like the other classical civilizations, had a patriarchal society with a set social structure. A womans most important role was to make a proper marriage that would strengthen the familys alliances. Widowed women were, however, permitted to remarry. Upper-class women were often tutored in writing, arts, and music, but overall, women were legally subordinate to their fathers and husbands.

Socially, the highest class was that of the scholar-gentry. These landlord families were often the only ones able to take the civil service exam, because preparation was very expensive. Most Chinese were peasants who worked the land. Merchants, who gained great wealth during this period with the increase in trade, did not enjoy high social status because they did not produce anything, but rather lived off the labor of others.

In China, the family became the most important cultural and organizational unit in society. The family consisted both of its living members and its ancestors. Confucianisms emphasis on filial piety, respect or reverence for ones parents, was also very influential. The family always provided for its own members.

Daoisms emphasis on being close to nature also had a lasting impact on China. This reverence for nature became a central value of the Han people. This was also a time of great invention and innovation. For many centuries, horses could not be efficiently used as draft animals. The solution, developed in China by the fifth century C.E., was to provide a collar around the neck and shoulders of the animal to distribute the weight. Collars of this kind reached Europe by the ninth century C.E. This development enabled the horse to become the main draft animal of Eurasia for both plowing and hauling. Agriculture was also aided by the wheelbarrow, while watermills were created to grind grain. The sternpost rudder and compass aided sea travel. Possibly most important was the invention of paper, which increased the availability of the written word.

Romes political history is one of change and evolution. In 509 B.C.E., the Roman nobility overthrew a tyrannical king, and what had been a monarchy became a republic—a government in which the people elect their representatives. The Roman Republic consisted of two consuls who were elected by an assembly that was dominated by the patricians, or wealthy class. The Senate, made up of patricians, advised these consuls. This system of leadership created tension between the patricians and the common people, known as the plebeians. Eventually, after a revolt, the patricians granted the plebeians the right to elect tribunes, who had the right of veto. When a civil or military crisis occurred, a dictator was appointed for six months.

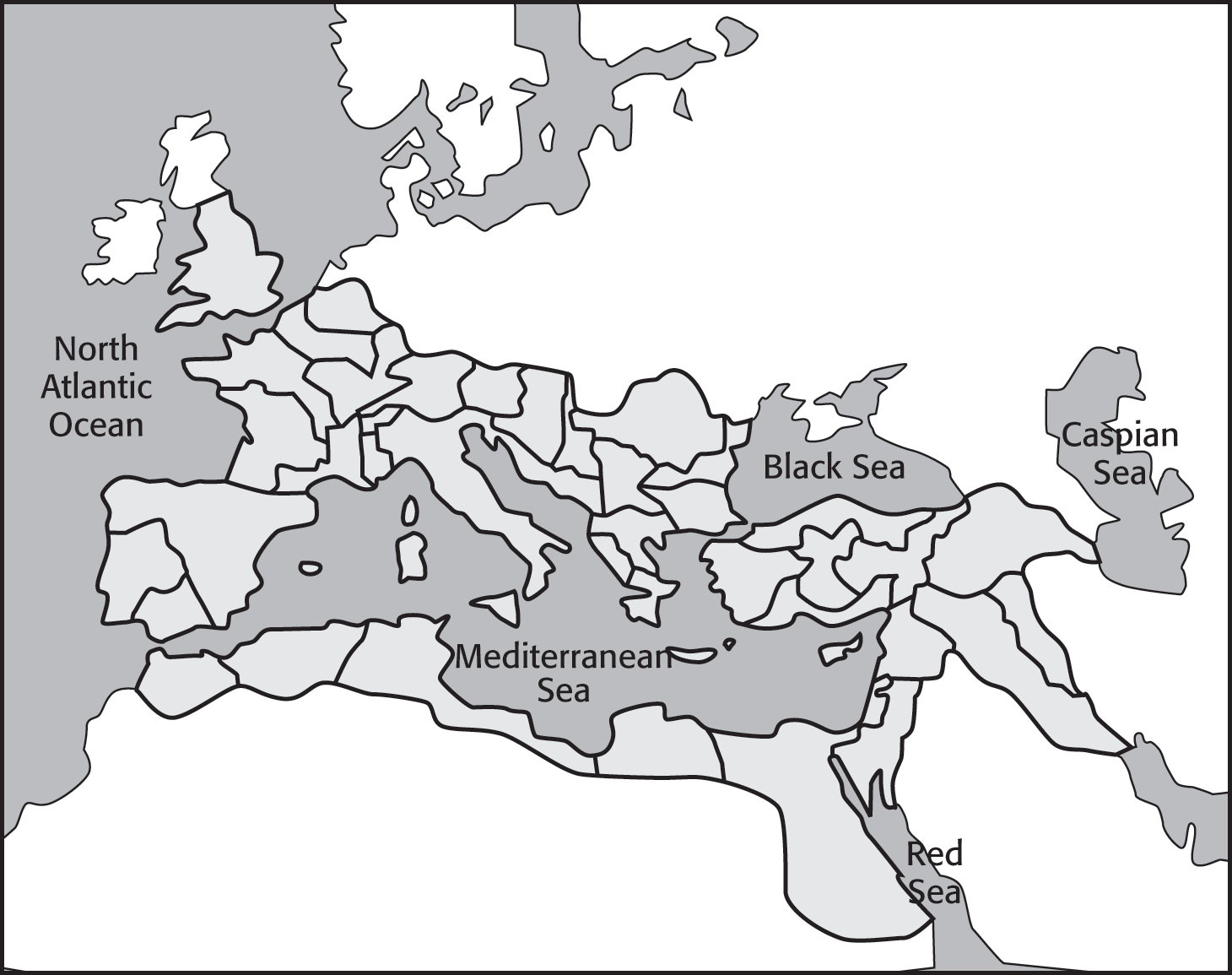

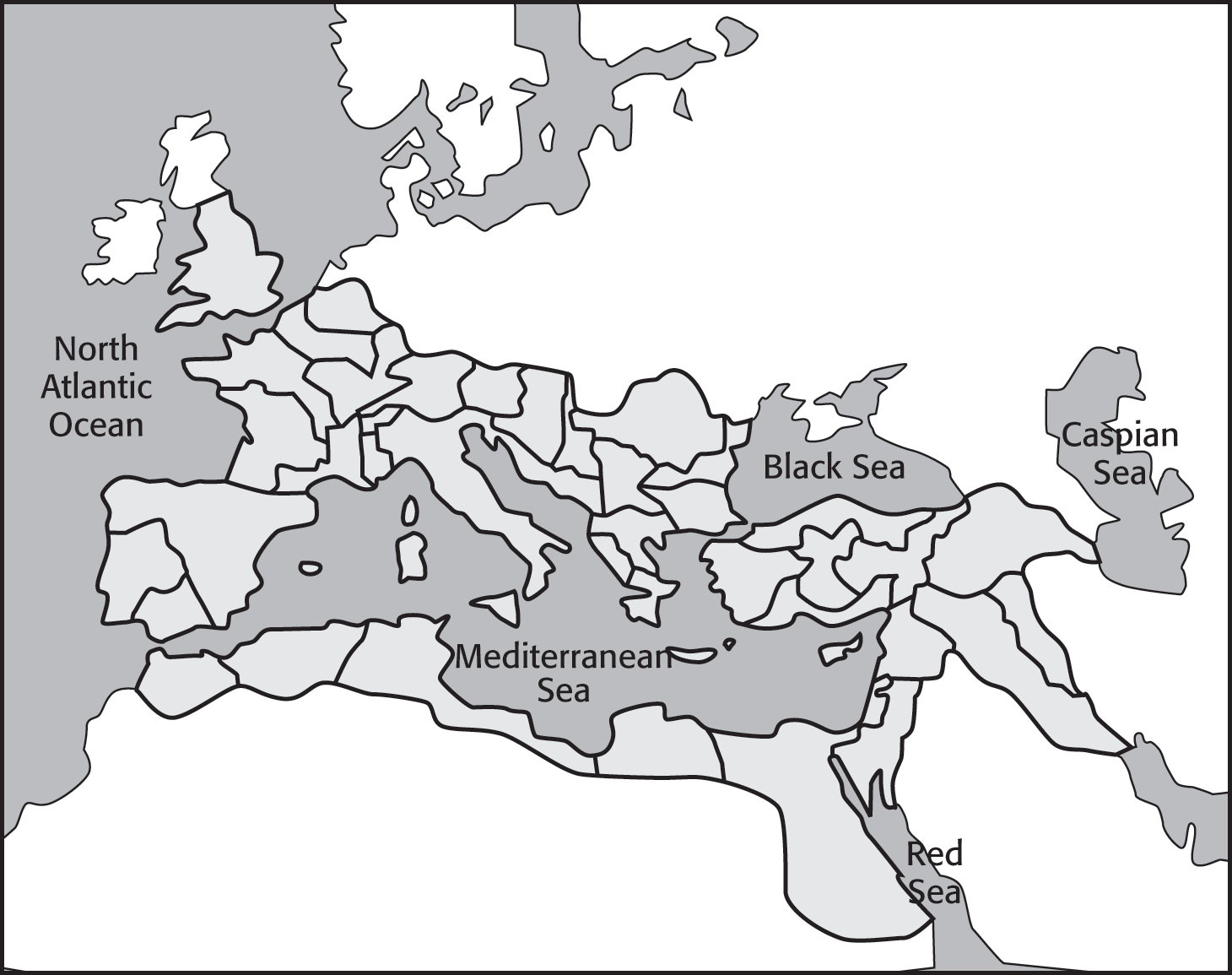

As Rome expanded throughout the Italian peninsula and then the Mediterranean, it encountered a fierce competitor in the city of Carthage. Located in North Africa, Carthage was initially a colony in Phoenicia. It gained wealth through the thriving trade in the Mediterranean region. This economic competition led to the Punic Wars, a series of three wars which took place from 264 to 146 B.C.E. By the end of the conflict, Rome had sacked the city of Carthage, solidifying Romes domination of the Mediterranean. Rome was also expanding east into Greece and the western coast of Anatolia, the former empire of Alexander the Great.

As Rome expanded, its republican system began to break down. The wealth and power resulting from conquest led to many problems, most notably the unequal distribution of land. The wealthy amassed large plantations using slave labor and the small farmers could not compete. Also, the growth of cities led to an increase in the urban lower class and an increase in poverty. Sporadic attempts by reformers to correct this inequality led to bloodshed, as the patricians and merchant classes resorted to violence to protect their wealth, defending their actions as saving the republic from would-be kings crowned by the plebeians.

Julius Caesar led a Roman army in its conquest of Gaul (present-day France). In 49 B.C.E. he seized Rome and soon made himself dictator for life. While fighting a civil war (49–45 B.C.E.) with the Senate, Caesar centralized military and political functions, undertook land reforms, and initiated large-scale building projects which gave jobs to the poor. Caesar pardoned many of his enemies in an effort to foster peace. After the end of the civil war, a group of senators feared Caesar aimed to become a king and assassinated him. His nephew Octavian took over. After another, shorter civil war, Octavian took the title of Augustus in 27 B.C.E. as the first Roman Emperor.

During Augustus’s 45-year rule, Rome was a monarchy disguised as a republic. The Senate continued to exist, yet only served as a rubber stamp for Augustus, who did not call himself a king or emperor but rather the humbler princeps civitatis (first citizen). The continued expansion of the empire stimulated the growing economy, and new cities emerged. Economic prosperity, centralized power, and the strength of the Roman army resulted in stability throughout the empire; the next two and a half centuries were called the Pax Romana, or Roman Peace.

The Roman Empires economic success was due to two key factors: its extensive system of roads and its access to the Mediterranean Sea. The 60,000 miles of roads linked the empires sixty million people, connecting all regions of the empire for trade and communication, and also allowing for the speedy transportation of armies. The Mediterranean Sea allowed for the transport of goods more cheaply than inland routes; the Romans kept the sea lanes clear of pirates. Taken together, these avenues of trade made the merchants very rich and created markets for the goods that the farmers produced. The resulting tax revenue strengthened the empire. A uniform currency was used, and while Latin was the language of politics and the Romans, Greek was the lingua franca (common language) for trade throughout the Mediterranean.

The extensive trade network made the empire very interdependent. Cities grew and so did their populations. The cities had access to fresh water through the use of aqueducts, sewers, plumbing, and public baths.

Like other classical societies, Rome was patriarchal, where the eldest male, the paterfamilias, ruled as the father of the family. Roman law gave the paterfamilias authority to arrange marriage for the children and the right to sell them into slavery—or even execute them. Womens roles were in supervising domestic affairs, and laws put strict limits on their inheritances, though this was inconsistently enforced. As the wealth of the empire increased, new classes emerged, and these new wealthy merchants and landowners built very large homes. On the other hand, the poor were often unemployed. Slaves, one-third of the population by the second century C.E., worked on large estates in the countryside or in the cities as domestic servants. Slaves served as everything from miners, tutors, prostitutes, farm laborers, and more.

Romes system of law had begun in 450 B.C.E. with the Twelve Tables—a series of laws that were organized into 12 sections and written down so they could be understood by all. As the empire spread, the laws spread with it. Such laws as innocent until proven guilty and a defendant has the right to challenge his accuser before a judge originated in Rome.

Much of Roman culture and achievements were inspired by Greek examples. Romans were polytheistic, like the Greeks, and believed that the gods intervened directly in their lives. The empire tolerated the cultural practices of its subjects, as long as they paid their taxes, did not rebel, and revered the emperors and Roman gods. The Jews, strict monotheists, who were scattered and generally accepted throughout the Roman Empire, were considered a problem in their homeland of Judea because rebellious groups often tried to overthrow the Roman rule. After a series of bloody rebellions in the first and second centuries, the Jews were completely defeated by the Romans and forced out of the city of Jerusalem. This was the start of the Jewish Diaspora (or scattering) and of the rabbinical form of Judaism.

Christianity, originally a Jewish sect, was also seen as a threat to Roman rule, and its followers were often persecuted. However, the number of Christians continued to grow throughout the empire. By 313 C.E., Emperor Constantine issued the Edict of Milan, which legalized Christianity. By 380 C.E., Emperor Theodosius proclaimed Christianity as the Roman Empires official religion.

Rome was heavily influenced by the Greeks in art and architecture as well. Roman architecture took its inspiration from Greece, making its columns and arches more ornate. Improvements in engineering, including the invention of concrete, allowed the Romans to build stadiums, public baths, temples, aqueducts, and a system of roads.