A CRIMSON TIDE

Chester Nimitz had had a bellyful. There were the day-to-day frustrations of managing war across the far-flung Pacific and the pressures of finding ships and planes to sustain his line commanders. His Washington masters demanded answers Nimitz did not have, and forced him to defend subordinates in whom he had his own doubts. Both King and Nimitz had lost faith in Frank Fletcher as Pacific carrier chief. King was very critical of Admiral Ghormley in the South Pacific. Early in September the COMINCH and CINCPAC held another of their periodic get-togethers at San Francisco, joined by Navy secretary James Forrestal, just returned from the South Pacific. Ernie King wanted assurances on Ghormley. Forrestal backed the SOPAC, which pleased Nimitz, but returning to Pearl Harbor the CINCPAC found a letter from Ghormley that revived his concerns. Between diatribes on British colonials, dark expressions of suspicion about Ernest J. King, and fears of diminished carrier strength (at a time the Wasp had yet to be sunk), Ghormley defended his cautious tactics and suggested he needed no greater authority—where many agreed operational command was precisely what SOPAC lacked.

Admiral Nimitz decided to visit the South Pacific himself. The seaplane carrying his party alighted on the water at Nouméa on September 28. The CINCPAC boarded flagship Argonne. Also there were General Henry H. (“Hap”) Arnold, leader of the Army Air Force, returning from an inspection of MacArthur’s command, and General George Kenney, who had come with Arnold for the conference. Nimitz got an earful. Bob Ghormley had worked in his little office on the Argonne for months. He had not left the ship, not to visit Marines on Guadalcanal, not even to coordinate with MacArthur. When Hap Arnold chided Ghormley for his sedentary manner, the SOPAC commander, his back up, told off the Army air boss in no uncertain terms. No one could question Ghormley on how he exercised command.

Nimitz and Ghormley both knew they had been pleading with the Army for planes. The CINCPAC also knew, even if Ghormley did not, that as an informal member of the Joint Chiefs, Arnold had resisted additional aircraft for the Pacific, even torpedoing already approved programs in favor of sending more to Europe. Only recently had Arnold agreed to provide some of the new, higher-performance P-38 fighters to the South Pacific. Antagonizing Hap Arnold was not smart, even less where Hap had a point. The SOPAC’s exhaustion was obvious even to George Kenney. “I liked Ghormley,” Kenney recorded, “but he looked tired and really was tired. I don’t believe his health was any too good and I thought, while we were talking, that it wouldn’t be long before he was relieved.”

There was more. Admiral Nimitz had discovered that the Washington, a new fast battleship assigned to SOPAC, had been left behind at Tongatabu, far from the battle zone. Ghormley pleaded fuel shortages. SOPAC was deficient on tankers, but the harbor was full of merchantmen awaiting cargo transshipment—theater logistics were a nightmare. And the admiral still resisted running warships up to contest the nightly Japanese dominance of Ironbottom Sound. Ghormley had been defensive on this when writing CINCPAC, and Nimitz nudged him now, suggesting he had been holding too tightly on to his cruiser-destroyer strike force.

Twice during the conference aides entered with action messages for the SOPAC, and both times the admiral seemed to have no clue what to do. Then came an eye-opening exchange between Ghormley and Kenney. SOPAC officers naturally appealed to the SOWESPAC air commander for mass strikes on Rabaul. Kenney replied that his airmen wanted to knock out Rabaul’s airfields, even burn down the town, but that several requirements of the New Guinea fight had to be met first. Kenney refused to say when Rabaul might be attacked. Admiral Ghormley responded that he appreciated what SOWESPAC was doing and wished them luck over Rabaul when they got there. Nimitz bristled at such flaccidity.

Next day Admiral Nimitz hopped a B-17 flight to Cactus. Even now Ghormley failed to seize the moment to visit the front. The aircraft went off course in stormy weather and found Guadalcanal almost by chance—CINCPAC’s air staff officer had to use a National Geographic map. They were an hour late, landing in rain, taxiing through mud, then disgorging Nimitz, disappointing Marines who hoped the plane carried nurses or chocolate. General Vandegrift, who wished Nimitz to see the real conditions under which his men fought, was privately pleased.

Vandegrift met the plane and squired the admiral around Henderson, then to see Bloody Ridge and some of the perimeter. Later they joined Roy Geiger for a nuts-and-bolts talk on flying planes from Cactus. The two boss men talked long into the night on everything from naval regulations to Vandegrift’s mission of defending Henderson, which he felt was threatened by Kelly Turner’s latest brainstorm—creating a new air base elsewhere on Cactus. It must have gratified Nimitz when the Marine, thinking about aggressive ship handling in Ironbottom Sound, advocated changing Navy regs to make skippers more venturesome, less anxious about running their ships aground. That was exactly what a young Lieutenant Nimitz had been charged with so many years before.

In the morning Admiral Nimitz awarded a number of medals, including the Navy Cross to Alexander Vandegrift. A dozen recipients were Cactus fliers. Then Vandegrift bundled the admiral into his B-17, wanting to get him out before rain turned Henderson into mud or the Japanese noontime raid hit. The aircraft failed on its first try and had to wait for a break in the weather. Back in Nouméa, Chester Nimitz ordered Ghormley to upgrade the facilities on Cactus, providing Quonset huts for the airmen, Marston mats for the entire runway, better fuel and ordnance storage, plus reinforcements. He overrode SOPAC’s objections about garrisoning islands far from the combat zone. Returning to Pearl Harbor, Nimitz professed himself satisfied with the situation in the South Pacific, though in truth he was far from happy. Admiral Nimitz told Time magazine the men on the spot “will hold what they have and eventually start rolling northward.”

TWO WALKS IN THE SUN

The advent of the 7th Marines afforded Alexander Vandegrift fresh opportunities. The Marine general was not content on the defensive. As a young officer he had served in China at the outset of its civil war and knew the costs of passivity, shown by the Chinese nationalists there. Happy to make an incursion with the Marine Raiders when he brought them over from Tulagi, Vandegrift did the same with his reinforcements now. He probed Japanese positions. Aerial photography showed the main body of Japanese stood west of a river called the Matanikau. The Marines knew little more than that. A probe would reveal the situation. It would also invigorate Marines who had sat far too long in their foxholes.

Vandegrift nominated Red Mike Edson to lead and told him to use any troops he wanted. Elevated to command the 5th Marine Regiment, Edson selected one of its battalions, included his old 1st Raider Battalion, and called on the fresh 7th Regiment for a unit too. The latter choice fell on Lieutenant Colonel Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller’s 1st Battalion, 7th Marines (1/7), a solid unit led by a famous Marine. The Raiders and the 1/7 were to swing to the south, skirting Mount Austen and crossing the river to establish precisely where the enemy might be. The 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, would be at the Matanikau’s mouth in reserve.

Nothing went according to Edson’s plan. The overland trek across foothills, through jungle and elephant grass, slowed to a crawl. Chesty Puller’s 1/7 tarried. The Marine Raiders got into a fierce firefight, climbed a hill to obtain better positions, and ended up defending themselves. Lieutenant Colonel Samuel B. Griffith, who had succeeded Edson in charge, was badly wounded and his deputy killed. Puller’s men followed the Matanikau to the sea, unaware the Raiders were trapped behind them. Chesty had sent a reinforced company back to base as bearers and guards for wounded, and these men were commandeered for a rescue mission to the Raiders. As a result of bombs that wrecked Vandegrift’s radio center, a message from Griffith had been misunderstood to mean the Raiders were on the far side of the Matanikau. So division called on Jack Clark of the naval support unit, who sent Higgins boats to carry the 1/7 Marines to save the Raiders. But there was no one to rescue, and the relief party was itself surrounded just inland from the beach. Puller and Edson were standing together at the river mouth when the Higgins boats chugged past, ignoring their frantic efforts to wave off the craft. Finally Puller boarded destroyer Ballard offshore and signaled his trapped men to move off in another direction. They were extracted, but not before Coast Guardsman Douglas A. Munro, diverting the enemy with some of the Higgins boats, fell dead. The fiasco cost 140 men.

September gave way to October, with General Vandegrift deciding to extend his perimeter to the Matanikau. He planned a new operation using six full battalions, almost half his troops, under direct command. This time most of Edson’s 5th Marines advanced along the coast; the 2/7 would cross the Matanikau and take up blocking positions, while Puller’s battalion and the reinforced 3/2 Marines made a right hook inland and marched to the sea. Puller would capture Point Cruz. The Japanese might be pocketed. In that case Edson should continue over the river, pass Point Cruz, and make for the enemy base at Kokumbona.

The operation began early on October 7. Red Mike quickly ran into trouble and asked for help. Vandegrift sent the 1st Raiders. All stalled. Blissfully ignorant of American plans and intent on reaching good jump-off positions for their own offensive, General Maruyama of the Sendai Division had ordered his Aoba Detachment to advance also. The result was fighting on both banks of the Matanikau. Rain delayed movement late into the next afternoon. Some Marines in the enveloping force wavered, and neither 3/2 nor 1/7 could complete the encirclement. That afternoon Vandegrift received a vexing dispatch from Ghormley. SOPAC intelligence believed a large Imperial Navy task force was on the way. Though by then he had three battalions across the river, Vandegrift decided to pull back and defend the Matanikau line. On October 9 Marines began laying out new defenses.

Japanese troops were indeed marshaling for a big push, though intelligence was wrong about timing. On their side everything depended upon the buildup. Arrival of the 2nd Sendai Division would be the leading edge, dribbling in from the Tokyo Express. Lieutenant General Maruyama Masao arrived between the first and second Matanikau battles. Maruyama’s October 1 order of the day—captured by the Americans—was highly suggestive. “This is the decisive battle,” Maruyama had said, “a battle in which the rise or fall of the Japanese Empire will be decided. If we do not succeed in the occupation of these islands, no one should expect…to return alive.” Lieutenant General Hyakutake landed on Guadalcanal on October 9 with his Seventeenth Army forward headquarters. His own plan echoed Maruyama’s, stating, “The operation to surround and recapture Guadalcanal will truly decide the fate of the control of the entire Pacific area.”

Hyakutake left his chief of staff, Major General Miyazaki Shuichi, at Rabaul as a relay between the battlefront and IGHQ. Lieutenant General Sado Tadayoshi’s 38th Division had begun moving up from Borneo, and liaison officers were already at Rabaul. Special provisions were made for the 150mm heavy guns of the Army’s 4th Artillery Regiment, supposed to help neutralize Henderson. A Navy delegation visited Guadalcanal to survey conditions and reported that for effective bombardment the guns would need to be on the west bank of the Matanikau—one reason the Japanese contested this ground so fiercely and ordered that Aoba Detachment attack.

The Tokyo Express had gone into high gear. Some troops would complete their voyage to Starvation Island by ant runs—the Japanese employed enough barges to deliver half a dozen loads every day. There were four rat missions during the last week of September, and the Navy ran the Tokyo Express almost nightly during the first half of October. The Army’s heavy equipment, in particular tanks and the 150mm guns, would arrive on a pair of missions by seaplane carriers Nisshin and Chitose. The long-ballyhooed “high-speed convoy” would deliver the balance of the Army troops. Hyakutake had scheduled his offensive for October 21. The Imperial Navy bent every effort to make that possible.

POTENT FORCES

In the South Pacific, Allied fleets deployed thin resources to meet vast demands. Destroyers were especially hard-pressed in SOPAC. Not only were they vital for convoy protection and to cross Torpedo Junction, but they had to sweep harbor entrances during the entry or exit of fleet units, screen the task forces, conduct antisubmarine patrols, protect oilers refueling the fleet at sea, bombard enemy shores, and engage the Japanese fleet. American ships maintained one of several levels of alert. The highest form of readiness, battle stations, was called Condition 1. In Condition 2 half the guns were manned and the ship prepared to maneuver. Condition 3 was for normal cruising. Vessels in these waters almost never set Condition 3. Battle stations were the norm every day at dawn, whenever approaching Guadalcanal, often in its anchorage, and anytime action impended. Mostly skippers set Condition 2. This cycle of constant medium to high readiness played havoc with men’s lives—sailors had to eat on the run or at their action stations, grab sleep when possible, and perform at peak despite their constant demanding work. Guadalcanal convoys were timed to enter the eastern approach, the Lengo Channel, before dawn, arriving early at the anchorage. Escort commanders decided whether to up-anchor and skedaddle when things got too hot. The importance of unloading usually had them standing in Ironbottom Sound when the JNAF came, though ships might get under way to avoid damage.

Task Force 64, the SOPAC cruiser-destroyer flotilla, had been reconstituted since Savo Island. Still, with SOPAC’s meager forces and the available warships constantly called upon for anything and everything, it was difficult to prepare for surface combat. Rear Admiral Norman Scott led the unit. Scott had skippered one of the light cruisers that escaped Savo because she had been in the anchorage to protect the transports. He had no intention of allowing that tragedy to repeat. The Imperial Navy had had better night tactics. Scott made his ships practice night maneuvers whenever they could be spared. Gunnery exercises were numerous. At least twice in late September, Admiral Scott held night maneuvers with his complete force.

The Americans had one key advantage with their radar, then a newfangled gizmo, and a word constructed of an acronym that stood for “radio detection and ranging.” The technical development of radar had gained momentum quickly. An SC-type radar used longer-wavelength pulses, well suited to detecting targets at altitude, hence its utility for discovering enemy aircraft. The innovation of powered revolving antennae increased coverage to a full 360 degrees, and that of the “planned position indicator” enabled radarmen to “see” targets in a spatial relationship to the emitter. This became the basis for the aircraft carrier’s practice of positive control over intercepting fighters, vectoring them to engage specific targets. The SC radar was becoming widely distributed and now equipped all battleships and aircraft carriers, many cruisers, and late-model destroyers. But with its long radio wavelength (150 centimeters), the SC equipment had poor target discrimination closer to the surface, where signals were absorbed by landmasses and vegetation or broke up amid wave action. A new machine, the SG-type radar, had a micro waveform (10 centimeters) that promised excellent performance close to the surface, discriminating ships from land, even vessels of different sizes, and this became the basis for radar-directed gunnery. So far only the newest vessels had that equipment. The Japanese were far behind, their first, primitive radars installed in the summer of 1942.

By October a number of Norman Scott’s warships featured SC radars, and a couple had the SG-type also. Integrating technology into seamanship posed the next great challenge. The use of radar data in gun laying was one headache—could it be translated directly into direction and azimuth instructions or should it be fed to gun directors? Another problem was the effect of gunnery on radar. In a number of ships, when main batteries fired, the radars were knocked off-line and had to be repaired. These problems would eventually be worked out, and the first practical solutions came at Guadalcanal.

When SOPAC knew the Tokyo Express was coming, Task Force 62, Kelly Turner’s amphibious force, might strengthen convoy escorts with cruisers, or Scott could bring his surface action group up to engage them. In October, the operating tempos of the two sides meshed to produce the first round of what became a crucial passage. Initial contenders were the JNAF and Tokyo Express versus the Cactus Air Force. Anxious to prepare the way for the Japanese Army, the Navy sent bombers by day, the Tokyo Express at night. With Nimitz still returning to Pearl Harbor, the South Pacific erupted.

The Eleventh Air Fleet opened with a fighter sweep on October 2. Bombers, included as decoys, turned back short of Cactus, and most of the Zeroes went on. Japanese airmen downed six Wildcats, including those of two pilots Nimitz had just decorated, damaging several more. Tsukahara’s fliers repeated the formula the next day, but Cactus air was prepared, dispatching nine JNAF fighters and badly hitting another. That was a critical day at sea also. Seaplane carrier Nisshin steamed down The Slot carrying nine of the Japanese guns, their gunners, and General Maruyama. Scout bombers found her late in the afternoon but were driven off by Zeroes. The SBDs jumped Nisshin that night while unloading. The ship sprang a leak from a near miss, and Captain Komazawa Katsumi cut short the mission with two artillery pieces still aboard. The Cactus Air Force struck twice again, missed, and B-17s tried their luck too, but were put off their aim by a Chitose floatplane crashing into a bomber, shearing off a wing. The responsible airman, Warrant Officer Katsuki Kiyomi, actually survived the collision and parachuted to safety.

The Americans attempted to come back the next day. Commander Air Solomons (AIRSOLS) arranged for Hornet planes to hit Shortland while Army B-17s struck the Buin complex. Amid cloud cover the attackers could not find their targets. That night the Express ran, as it did on October 5, when Cactus fliers pounded the destroyer sortie, damaging two ships. Mikawa assigned light cruiser Tatsuta and seaplane carrier Chitose to augment the Reinforcement Unit, now facing a backlog of matériel to land, including eight of the 150mm howitzers plus a number of other artillery pieces.

Coastwatchers and aerial reconnaissance assumed primary importance. Radio intelligence had temporarily been blinded. On September 30, the Imperial Navy modified its entire system of communications, copying some U.S. methods, changing call signs, and introducing a revised D Code (the Japanese name for JN-25). At that moment the most recent CINCPAC monthly estimate had a good understanding of Mikawa’s fleet strength. Weekly reports on Japanese fleet dispositions issued in Washington by the F-22 section of the Office of Naval Intelligence, based primarily on radio direction finding, agreed with CINCPAC’s accounting in dispatches sent on September 29 and October 6.

Pearl Harbor credited the JNAF with twelve to eighteen floatplanes and two patrol bombers at Shortland, and twenty-seven medium bombers, forty-five Zeroes, forty-eight floatplanes (half scouts, half the Zero seaplane version), and a dozen patrol bombers in the Rabaul area. Intelligence assessed that forty-five Zeroes and fifty-four Bettys were in the pipeline to the front.

Officers commented on Japanese intentions in their appreciation of October 1: “For the past six or seven weeks the Japs have been assembling planes, troops and ships in the general Rabaul area. There are no indications whatever of a move in any other direction.” But Pearl Harbor was complacent: “While the Japs may want to start such an [offensive] effort in the near future,” they had suffered heavy losses already, with Allied planes and submarines taking a steady toll, so that “all this has definitely slowed up their preparations.” CINCPAC tabulated Japanese losses and damage during September at several aircraft carriers, an equal number of cruisers, a battleship, plus lesser vessels, a distinct overestimate. In reality Yamamoto’s fleet was at its greatest strength since the invasion.

Disturbing indications mounted. The CINCPAC bulletin on October 6 mentioned Army and SNLF troops in the Solomons and predicted an impending attempt to overcome the Marines. Two days later the bulletin expected constant Tokyo Express runs, and the fleet intelligence summary noted the flow of aircraft to Rabaul, located the Sendai Division’s chief of staff on Guadalcanal, and commented that the Japanese Seventeenth Army was “increasingly associated” with the island. Next day Admiral Mikawa was thought to have gone to Buin. Then, on October 10, the CINCPAC summary mentioned the Nagumo and Kondo forces in relation to the Solomons, again associated the Seventeenth Army with Cactus, located the Sendai Division as possibly on the island with the Kawaguchi Brigade, listed several SNLF units as “implicated” in the islands, and ominously led with this: “The impression is gained that the enemy may be getting ready for larger-scale operations in the Guadalcanal area.” According to codebreaker Edward Van Der Rhoer, Op-20-G—hence Washington and presumably Pearl Harbor—knew the Japanese would lead off with a cruiser bombardment of Henderson.

The fat was in the fire. At SOPAC, Admiral Ghormley finally agreed to send U.S. Army troops to Cactus, and the 164th Infantry Regiment began loading out on October 8. Their move would be covered by the Hornet task force. The Japanese were intent on completing their transport schedule. Early on October 11 they put in motion the latest heavy reinforcement, employing both the seaplane carriers Chitose and Nisshin bearing artillery, and half a dozen destroyers in escort, most bearing troops. A daytime JNAF fighter sweep followed by a bomber raid tried to cripple the Cactus Air Force, which had just opened Fighter 1 to supplement Henderson Field. Weather and interceptors rendered the strikes ineffectual. But there was a third arrow in the Japanese quiver, a cruiser group sent to administer a naval bombardment. The enemy was bearing down at that very moment.

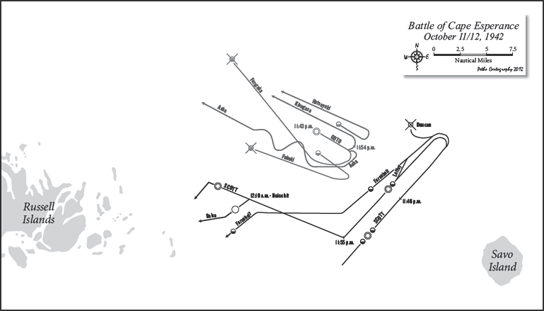

Norman Scott’s surface action group left Espíritu Santo on October 7. With just three cruisers and three destroyers, Task Force 64 was on the weak side, and at the last moment other warships in the area, light cruiser Helena and a pair of destroyers, joined Scott. Helena sported one of the new SG radars. Admiral Scott wanted to hunt. He had a healthy awareness of Tokyo Express activity and a desire to avenge Savo. From west of the Solomons, Scott closed The Slot, timed to arrive off Savo near midnight, then steamed back to his holding position. For two nights Task Force 64 encountered nothing. On the third, the night of October 11–12, Scott found game. On Guadalcanal, Cape Esperance happened to be the closest point, and the battle took that name.

Rear Admiral Goto Aritomo led the Japanese flotilla, composed of three ships of his own Cruiser Division 6 plus two destroyers. A thirty-two-year Imperial Navy veteran, Goto was a torpedoman and had led the Navy’s premier night-fighting unit before taking up these heavy cruisers, which had fought at Guam, Wake Island, and the Coral Sea before their stupendous Savo victory. Goto missed at least two chances for warning: Commander Yokota Minoru’s I-26 had seen a U.S. cruiser but radioed the information too late, while the Japanese reinforcement group unloading at Guadalcanal, which Scott’s force must have passed, apparently saw nothing. The Japanese had no radar, but they had honed their night skills, with specially trained lookouts and excellent equipment, including low-light, high-magnification glasses.

Admiral Scott’s Americans, on the other hand, only beginning to experience the use of radar, nearly squandered that advantage. Light cruiser Helena detected Goto first, at almost fourteen nautical miles, closing at thirty-five knots. Helena, which had never operated with Task Force 64, did not report her sighting. Heavy cruiser Salt Lake City also detected the Japanese with her less advanced SC radar, but remained silent. So did light cruiser Boise, with an SG radar, which assumed Admiral Scott had the information. Helena finally passed along her sighting at 11:42 p.m., and a couple minutes later Boise did too, but ambiguities in language and navigation terms left confusion as to the Japanese position and even whether there were different groups of them. By that time the range had shrunk to less than 5,000 yards, and Goto’s vessels were plainly visible. Aboard the Helena an officer grumbled, “What are we going to do, board them?”

Lookouts on the Japanese flagship, heavy cruiser Aoba, finally saw three U.S. vessels at 11:43. Admiral Goto tentatively reduced speed to 26 knots, but just a moment later the Helena opened fire followed by the rest of Scott’s ships. Goto had been steaming directly at the Americans, disposed in a line across his course, creating the sailors’ dream of “crossing the T” of an adversary, where all guns could shoot at the enemy, who could reply only with weapons on the bow or stern. The Aoba, leading the Japanese line, was quickly reduced to a wreck, both forward eight-inch gun turrets smashed, her bridge hit by heavy-caliber shells. The Boise landed a salvo, including a dud shell on the flag bridge that mortally wounded Goto and killed two of his staff. Rear Admiral Scott, worried his ships were shooting at one another, ordered a halt, resuming fire once he felt more confident.

The Japanese force disintegrated. Aoba veered to port to bring her broadside to bear, only to offer the Americans a bigger target. She staggered off, struck more than forty times, but lived to fight another day. Saima Haruyoshi, a petty officer with the damage control detail, was sleeping at his battle station in the stern when the shells began to fall. He did not feel the first hit, but after that, destruction came quickly. One shell wrecked the number three turret, in the compartment immediately forward. When Saima tried to open the hatch, flames drove him back. There were dead, wounded, and fires everywhere. They had to pile up the bodies to get at the fires.

Destroyer Fubuki, haplessly caught as Scott steamed across her course, was blasted to pieces. Captain Araki Tsutau of the Furutaka, second in the Japanese line, turned to starboard, followed by the Kinugasa. The Furutaka came around to support her flagship, sustaining more than ninety hits, but she scored twice on the Boise, once against a forward magazine. The shell, of a type the Imperial Navy had designed to hit water and travel beneath the surface to impact a ship hull, actually functioned as advertised, recording the only known wartime success for this munition. The magazine hit would have blown Boise up save that seawater pouring into her from the hole extinguished the fire. Furutaka finally succumbed. The Kinugasa was slammed four times but punched back at the USS Salt Lake City with eight hits. Aoba was badly damaged. The Imperial Navy vessels survived the huge numbers of hits due only to high-quality design, brave seamen, and the proportion of duds among the American shells.

The Boise would be out of action for six months, the Salt Lake City for a full year. And Admiral Scott had not been entirely wrong about friendly fire—destroyers Farenholt and Duncan were both hit by U.S. shells, the latter mortally.

Goto Aritomo’s death sent shudders through the Imperial Navy. Goto was the first Japanese admiral to die on his bridge in a surface battle. Yamaguchi Tamon had gone down with flagship Hiryu at Midway, but he had elected to stay behind when sailors were abandoning ship. Worse, Navy gossip had it that Goto died believing the Aoba a victim of friendly fire, not enemy action. After Aoki Taijiro, captain of the carrier Akagi at Midway, Goto became the second member of Etajima’s class of 1910 to succumb in the war. That was important to a lot of Imperial Navy officers who, at that very moment, were leading the fleet against the Americans on Cactus. Among Etajima classmates on the scene were Goto’s boss, Mikawa Gunichi of the Eighth Fleet; Kusaka Ryunosuke, chief of staff of the Kido Butai; and Kurita Takeo, leading a force of battlewagons. His close friends included destroyer master Tanaka Raizo, now heading Kido Butai’s screen, and battleship commander Abe Hiroaki, both of whom had been a class behind Goto; as had Hara Chuichi, driving a cruiser division in Abe’s Vanguard Force. The Japanese officers redoubled their determination.

“WHERE IS THE MIGHTY POWER OF THE IMPERIAL NAVY?”

Marines had standing orders to examine the dead enemy for documents that might help divine intentions and movements. Many Japanese defied orders not to keep diaries. These were fodder for the Americans, part of the pillar of combat intelligence. Some documents Vandegrift’s staff exploited immediately. The bulk went to Nouméa, where SOPAC translated and examined them. During the second Matanikau battle a captured diary, translated at SOPAC, yielded a soldier’s plaintive cry, “Where is the mighty power of the Imperial Navy?”

The complaint hardly needed to be heard. Admiral Yamamoto issued preparatory orders for his fleet sortie on October 4. The Tokyo Express chugged, and the Eleventh Air Fleet roared into Cactus, but it was a race with the Americans. The morning after Cape Esperance, the U.S. convoy bearing the 164th Infantry arrived. Destroyer Sterett, among its escorts, dropped anchor. Unloading had barely begun when the air raid sirens sounded and the ships weighed again. On the bridge, Lieutenant Herbert May grabbed the skipper and pointed to planes breaking through the clouds. “Christ, Captain—look, there’s a million of ’em.” Lieutenant C. Raymond Calhoun, Sterett’s gunnery boss, fired the main battery at maximum elevation to disrupt the Japanese V-of-Vs formation; then they were past. Calhoun watched. “The pilots exhibited excellent discipline. They kept tight formation and never wavered…. Their aim was excellent and we watched a perfect pattern fall smack on Henderson Field.” Several hours later the JNAF repeated the performance in every detail save direction of the attack.

The Cactus Air Force got in its own licks. They helped track down Cape Esperance survivors, and they attacked destroyers that had been detached from the Japanese artillery convoy to rescue them. One enemy warship, crippled, had to be scuttled. Meanwhile, sharp as they had looked from the Sterett, Japanese bombardiers did not actually crater Henderson, so U.S. missions continued into the afternoon, blasting another destroyer to the bottom. Undeterred, Rear Admiral Joshima, the R Area Force commander leading the mission, immediately sailed on another artillery run in the Nisshin.

Yamamoto’s operation gathered momentum. Combined Fleet planned to wallop Henderson in conjunction with the sailing of the high-speed convoy. This would open with a battleship bombardment—the C-in-Cs notion of putting the Yamato alongside Guadalcanal—followed by heavy cruiser shellings on succeeding nights. In a way Yamamoto’s flagship would be at Guadalcanal—Yamato had sent expert lookout Lieutenant Funashi Masatomi to the island as an observer and installed him atop Mount Austen with radio gear.

The morning after Cape Esperance, Vice Admiral Kurita Takeo and his bombardment force, led by battleships Kongo and Haruna, left the main body. Suffering from fevers a few days earlier, Kurita was back on his mark. Rear Admiral Tanaka escorted. Battleship Kongo carried incendiary AA shells of a new type, tested at Truk in early October, which promised to be very effective. Haruna had older shells that could still be destructive. Theirs became the first opportunity to avenge Goto’s death.

For a prelude, Admiral Kusaka Jinichi sent his Rabaul bombers to hit Henderson, flying a course like the Sterett had seen—out to sea, avoiding coastwatchers and approaching from the south. This time the runway was damaged. Then the Japanese Army chimed in with the first shells from its 150mm howitzers, quickly christened “Pistol Pete,” impeding American efforts to repair the Marston matting. Kusaka followed with several night intruders that arrived at intervals, twin-engine Nells the Marines knew as Washing Machine Charlie.

Kurita arrived off Guadalcanal late in the evening of October 13. He made a high-speed circuit of Savo, set an easterly course past Lunga Point, then swung onto the reciprocal track, with the two battleships’ fourteen-inch guns pummeling Henderson and the U.S. positions for ninety minutes. Kurita launched floatplanes to illuminate the scene. The warships pumped out 918 shells, mixing their time-fused incendiaries with armor-piercing shells, both to destroy aircraft in the revetments and to dig under the runways. Captain Koyanagi Tomiji had his Kongo space her salvos at one-minute intervals. The pace allowed Lieutenant Commander Ukita Nobue, gunnery officer, to ensure accurate gun laying. Marine shore batteries that replied—they were beyond range anyway—were engaged by the battleships’ secondary armament, and searchlights were used to blind the Marine gunners.

Those on Guadalcanal remember this simply as “The Night.” General Vandegrift, who records that he used to go to sleep every evening about 7:00, after listening to the shortwave broadcast from San Francisco, refrains from commenting on The Night, though he surely must have awoken. In the same passage Vandegrift notes his first act every morning was to inspect the previous night’s damage. Marine Bud DeVere, a control tower operator at Henderson’s “Pagoda,” recalls a continuous ordeal of Pistol Pete shooting them up, Washing Machine Charlie harassing them, then the battleships. At Cactus Crystal Ball, radioman Phil Jacobsen was trying to relax in a bunker the Seabees had built to protect their intercept gear when he saw a star shell burst almost directly overhead. He had barely sought cover when all hell broke loose. After The Night, whenever it rained, their receivers went on the blink.

Lieutenant Bill Coggins, with 2/1 rifle battalion, located a full mile from Henderson, remembers the Marines had become inured to naval bombardments, but that, from the beginning, everyone realized this was different—star shells, tight six-gun salvos, heavy blast concussion. Far away though they were, the baseplate of a fourteen-inch shell landed awfully near the E Company cookhouse. When greenies of the Army’s 164th Regiment arrived to replace Coggins’s men the next day, wily Marines frightened them with promises of greater horrors to come. Captain Nikolai Stevenson, whose C Company of the regiment’s 1st Battalion was relieved that night by Army newbies, pulled into reserve near Henderson. He was playing poker when the fireworks started. “All at once the murmuring night exploded into ghastly daylight…. The concussion knocked me halfway over as I dived headlong for the puny cover of the ditch, where I lay shaking among the fallen palm fronds.” Japanese shells roared and screeched, like subway cars tearing through a thousand bolts of cloth strung together. Warren Maxson, also of the 1st Marines, counted five air raids that night. Lieutenant Merillat of Vandegrift’s staff remembered the alarming series of “Condition Red” alerts—always announced by siren for incoming air raids—followed by the bombardment: “The shelter shook as if it were set in jelly. Bombs, artillery, big naval shells made it sheer hell.”

From an American point of view the one good aspect of The Night was that it marked the appearance of a new piece on the board, the Patrol Torpedo (PT) boat. These high-speed seventy-foot craft, each armed with .50-caliber machine guns, a 20mm cannon, and torpedoes, would contest Ironbottom Sound full-time. The convoy that brought Army troops had also deposited the first elements of PT Squadron 3. They based at Tulagi. Four PTs came out to fight Kurita’s fleet, attacking shortly before the bombardment ended. Commander Ukita on the Kongo recalled the PT boats’ intervention, but stoutly insisted Kurita’s worst fear was of running aground on the treacherous shoals and reefs in the channels. Destroyer Naganami contemptuously brushed off the PTs, but those gnats would be back, gnawing painfully at the Imperial Navy.

By morning Cactus had descended into crisis—Henderson Field holed, Fighter 1 damaged. Only seven SBDs and thirty-five fighters could fly; forty-one men were dead, including two more of those Admiral Nimitz had decorated so recently. The Pagoda was demolished. Roy Geiger ordered it bulldozed. Aviation gas was mostly destroyed, enough left for just one mission. Mechanics worked desperately on crippled planes. This was the day of the high-speed convoy, which had left on the thirteenth with six transports and eight destroyers. Scout bombers found both it and a fresh Japanese surface force—Admiral Mikawa with cruisers Chokai and Kinugasa—the latter bouncing right back to seek vengeance for Cape Esperance. Naturally, Japanese bombers struck at midday. Only late that afternoon did Cactus scrape together a flight of four SBDs and seven Army fighter-bombers to fling at the convoy. Draining the gas out of a couple of B-17s permitted a second wave of nine SBDs before dark. They achieved nothing save the loss of one plane and the crash of another.

Now the night cast Mikawa Gunichi as avenging angel. His cruisers lashed Henderson with 752 eight-inch shells. U.S. radio intelligence reported Mikawa at sea, probably in Chokai, that very day, but Cactus had had to choose between cruisers and convoy. While nowhere as destructive as Kurita’s battleship bombardment, Mikawa’s shells inflicted more damage on planes and renewed the craters that pockmarked airfields.

To complete their mastery of Ironbottom, the Japanese may have sent a midget submarine sortie into the anchorage. Orders for the mission exist. It was to have been launched from seaplane carrier Chiyoda, which had shuttled eight of the craft to the Solomons. These small two-man subs, notably used at Pearl Harbor and at Sydney, Australia, were to invade the sound around midnight. But there is no evidence of their actual presence. Some American small craft, escorted by a pair of the new PTs, crossed undisturbed from Guadalcanal to Tulagi that night. Admiral Ugaki complained that plans for the midgets’ employment were incomplete, and notes that he ordered a study, puzzling since Combined Fleet staff had discussed using the subs in the very first days of Watchtower. Ugaki recommended putting the boats at Kamimbo and loosing them when there were suitable targets. It is not clear whether Yamamoto overruled him. The Japanese did set up a midget sub base at the designated place, and other sorties did run from there. Months later the American salvage ship Ortolan found a midget and raised her long enough to recover this day’s attack order and other documents, but a storm broke her grip and the submersible was lost.

At dawn on the fifteenth, Marines were outraged to see Japanese transports unloading in broad daylight across the sound. But Cactus air was in disarray. Roy Geiger demanded his men find gas, and they did—an officer remembered fuel barrels had been cached in swamps and groves, and several hundred were found and laboriously hauled to the strips. That brought two days’ supply. Guadalcanal called upon SOPAC to fly gasoline aboard its daily flights and even bring a load on submarine Amberjack. Mechanics rushed repairs. Starting early, scratch flights of SBDs and Army planes took off to hit the transports at Tassafaronga Point. Fighters engaged R Area Force floatplanes and Japanese interceptors—ominously, from Kido Butai’s Carrier Division 2—to open the way, strafing ships when they had the chance.

Mitsukuni Oshita, a chief petty officer on destroyer Hayashi, was impressed at the way the Americans pressed their attacks in the face of murderous flak. Half the Japanese transports, damaged, withdrew. The others, also damaged, were beached—hopefully to be emptied later. The Nankai Maru and Sasago Maru were hit by the first U.S. wave, Azumasan Maru in the second attack, the Kyushu Maru later. An American bomb wrecked the Kyushu Maru’s wheelhouse, killing her captain and all the bridge crew. Ignorant of this, the ship’s engineers kept her at full speed until she ran up on the beach. The ammunition aboard another ship cooked off and she blew up. The Nankai Maru, the only cargoman not to catch fire—and the only damaged ship that tarried to unload—would be the only vessel of this group to escape. Men of the Independent Ship Engineering Regiment struggled to unload the supplies. The Japanese estimated the ships were 80 percent emptied. They would be furious in turn when U.S. warships appeared to shell the stacked supplies, destroying many. Beach crews were heavily hit too, with the regimental commander killed and one of his companies wiped out but for eight men.

Yet the Army troops had landed. They could not be stopped. With a Tokyo Express on October 17 the program was fulfilled. Captain Inui Genjirou brought his 8th Antitank Company, now without any guns, to help move the supplies. The men were so exhausted he had to rest them for a day, and they could do little to combat the fire that broke out in a nearby dump. But one of Inui’s companies, thrilled to get cigarettes, labored to move the rice sacks away. Inui himself enjoyed the first coffee he had had since leaving Java.

General Geiger so focused on the supply battle that the day’s Japanese air raid went virtually uncontested. Come night the Imperial Navy returned. This time it was Rear Admiral Omori Sentaro with heavy cruisers Myoko and Maya. Commander Nagasawa Ko, whose home prefecture of Fukushima would be devastated by tsunami and the nuclear meltdowns of 2011, was Omori’s senior staff officer and recalled later that the Japanese had expected to be sunk. On the Myoko the crew were given rifles and instructed to get to shore and fight as naval infantry. Instead they faced no opposition. The warships pounded Henderson Field with 1,500 more eight-inch shells (some sources report 926). Yet next morning the Cactus Air Force could still fly ten dive-bombers and seven Army fighter-bombers. Geiger’s maintenance crews plus the Seabees literally saved Guadalcanal.

American commanders recognized the crisis even if the Japanese did not. And they spoke up. Vandegrift cabled SOPAC and demanded every ounce of backing. Slew McCain, the AIRSOLS commander, did the same. Ghormley repeated the essence of their appeals in a dispatch to Nimitz. And the SOPAC had Rear Admiral George D. Murray’s Hornet task force mount a carrier raid on the R Area Force floatplane base at Rekata Bay. Results were indeterminate.

At Pearl Harbor, Admiral Nimitz decided he had had enough. Ghormley’s dispatch struck him as more weak-kneed passing of the buck. Aircraft carrier Enterprise, having completed repairs, was rushing to the South Pacific to increase the Allies’ paper-thin strength. Vice Admiral William F. Halsey, whom CINCPAC had appointed to lead the “Big E’s” task force, had gone ahead to get a feel for the situation. Nimitz huddled with his inner circle late into the night discussing the SOPAC command situation. On October 16, Admiral Nimitz asked Admiral King for authority to substitute Halsey for Ghormley. The COMINCH approved. Just as “Bull” Halsey reached Nouméa, Nimitz sent him a message: The Bull would supplant Bob Ghormley as theater commander. The aggressive Halsey led the next battle, the most important yet. Allied leaders already knew it was upon them.

BLOOD UPON THE SEA

Despite the Imperial Navy’s changed codes and communications, Allied intelligence assembled an increasingly alarming picture of its activities. Indications piled up from radio traffic analysis, from the coastwatchers, from combat intelligence, from observation and aerial reconnaissance, even a few from Ultra proper. After Cape Esperance—itself an intelligence windfall, because the Allies captured 113 survivors of the warships Furutaka and Fubuki, whom they plied for information—the picture darkened further. Starting the next morning, the Allies observed a rapid increase in the volume of messages sent on the Japanese radio nets, especially those used to report radio fixes on Allied ships. Meanwhile a snooper discovered Kido Butai, reporting carriers, battleships, cruisers, and destroyers 400 miles northeast of Cactus. Intelligence also detected the enemy intercept of that scout’s message, plus Imperial Navy sighting reports, an increasing number of them from I-boats. The fighting around Cactus certainly indicated the Japanese were not giving in.

The captured seamen revealed to Allied intelligence the actual Imperial Navy vessels engaged at both Cape Esperance and Savo, furnishing information that was accurate, if not at first believed, because it did not accord with the claims of U.S. commanders. Richmond Kelly Turner circulated this data on October 21. The prisoners knew nothing of Yamamoto’s current plans, but they possessed a wealth of knowledge of Japanese procedures, equipment, and operational methods.

On October 15, codebreakers reported that the pattern of radio traffic showed Yamamoto had taken direct command of operations. Combined Fleet became a heavy originator of messages. Ultra also provided radio bearings for a fleet unit containing at least two aircraft carriers, and reported an unidentified radio emitter on Guadalcanal—likely Lieutenant Funashi’s Navy observation post—that had begun providing fairly accurate tabulations of Cactus air strength. The next day Ultra confirmed the traffic flow from Combined Fleet and reported that the Japanese appeared to have focused all their attention on the Solomons. Pearl Harbor was on edge. The CINCPAC war diary for October 17 read, “It now appears that we are unable to control the sea…in the Guadalcanal area…our supply of the position will only be done at great expense.” Nimitz did not believe the situation hopeless, but it had become critical: “There is no doubt now that Japs are making an all-out effort in the Solomons, employing the greater part of their Navy.” Ultra noted quiet, or an unchanged Japanese situation, over several succeeding days. Starting on October 19, Ultra tabulated a reduction in high-level, high-priority message volume, ominously suggesting Yamamoto’s offensive was under way. The next day it furnished a new location for the Kido Butai and associated carrier commander Nagumo with surface fleet boss Kondo.

But Allied intelligence was not omniscient. As had happened before the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, there were doubts about the Japanese aircraft carriers. The Combined Fleet had five of these ships, with the large carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku, plus the light carrier Zuiho in Carrier Division 1, and the slower fleet carriers Hiyo and Junyo in Carrier Division 2. At the end of September, Washington’s weekly estimates located Carrier Division 1 not far from Rabaul, when it rode at anchor at Truk, except possibly the Zuikaku, which intelligence believed en route to Yokosuka. A week later it put the Zuiho also in Japan—and continued to believe the Zuiho in Empire waters right through the estimate of October 20, the last to appear before the battle. The Zuikaku the Allies estimated back in Truk on October 13, and they continued to place Carrier Division 1 there a week later, even though Japanese carriers had already been seen at sea, with locations for them repeatedly remarked in Ultra.

The record for Carrier Division 2 was worse. It was continuously placed in Empire waters right through the estimate of October 27, the day after the impending battle. The combat intelligence unit at Pearl Harbor wavered on locating these carriers, indicating they were in Japan on October 6, reporting a “slight” possibility of the Philippines on October 11, and a possibility the two ships might be in Empire waters a week later. In reality, Rear Admiral Kakuta Kakuji’s Carrier Division 2 had sailed from Japan for Truk on October 2 and sortied for the operation with the rest of the fleet nine days later. At least Pearl Harbor consistently believed that two big carriers were involved, and held them to be Shokaku and Zuikaku. On October 23, Pearl Harbor intelligence shifted to declare that “at least” two carriers must be among the enemy fleet.

Estimates for surface gunnery ships were skewed because Admiral Norman Scott reported inflicting much greater losses at Cape Esperance than was true. There was also another complication, according to Commander Bruce McCandless: ONI mistakenly believed all four Aoba-class cruisers lay at the bottom of the sea. When Scott claimed on October 18 to have sunk three heavy cruisers and four destroyers and possibly dispatched another tin can and a light cruiser (actual losses had been one heavy cruiser and one destroyer), these were scored to units other than the Imperial Navy’s Cruiser Division 6, which had the Aobas. This effectively minimized Japanese heavy cruiser strength. When the Myoko and Maya bombarded Cactus, ONI believed the former was anchored at Yokosuka and the latter at Palau. As for battleships, the October 20 estimate carried as “possibly damaged” one of Admiral Kurita’s vessels that had smashed Cactus on The Night, placed the Yamato and Mutsu as possibly at Rabaul, and credited the fleet in the Solomons—again “possibly”—with the Ise, then in Empire waters.

Fortunately other pillars of intelligence clarified. The combination continued to furnish a clearer picture. Rabaul would be covered by aerial photography at least a half dozen times during the last ten days before the battle. Estimated aggregate tonnage there ranged between 170,000 and 250,000 tons. At the high point, Simpson Harbor contained two oilers and forty-one merchant ships, with a light cruiser, a minelayer, three destroyers, and several aviation tenders. General Kenney’s SOWESPAC B-17s finally kicked off their Rabaul bombing on October 22, claiming to have blasted a cruiser, a destroyer, and eight merchantmen for 50,000 tons, and, two nights later, to have left the Nisshin wreathed in flames from a direct hit amidships, claiming her utterly destroyed. The Nisshin was at Shortland that night and no ship of her type lay at Rabaul.

As for Admiral Kakuta’s carriers, the first to intervene at Guadalcanal when he sent fighters to help screen the high-speed convoy while it unloaded, a scout plane signaled a carrier northwest of Kavieng on October 16, which put new light on the arguments over Carrier Division 2’s location.

The Japanese center of gravity had to be the Shortland-Buin complex, and there Allied intelligence benefited from coastwatchers as well as aerial spies. Reports covered that area virtually every day. Interestingly, the several separate forces counted here on October 15 totaled two aircraft carriers, four battleships, seven heavy and an equal number of light cruisers, twenty destroyers, and three aviation ships. An oiler and seventeen cargomen were reported the next day. If the intelligence estimates on Imperial Navy disposition were to be believed, those figures could not be accurate. But Kurita’s battleships stopped here briefly after The Night, Kondo’s fleet with Kakuta’s carriers were in the area, and Shortland was the center of Mikawa’s Eighth Fleet operations, with his typical tally some cruisers, aviation ships, and a dozen or so tin cans. The net impression, perfectly correct, was of Japanese might assembled for a big blow.

American air reconnaissance on October 17 recorded two cruisers and seven destroyers, and noontime aerial photography on October 20 revealed a heavy cruiser, four light cruisers, and seventeen destroyers. The other vessels were gone. Additional overhead imagery the next day disclosed the presence of five additional warships, with a different mixture of the cruiser types. On October 24 there was nothing at Shortland but a few tin cans. Over subsequent days sightings of all kinds showed Mikawa’s base reverting to its usual strength. The specifics could have been mistaken. What was inescapable was the sense of a mission force assembled, then launched.

Chester Nimitz did not need a weatherman to know which way the wind blew. SOPAC’s forces were divided among its cruiser-destroyer group, a unit with new battleships Washington and South Dakota, now titled Task Force 64, and the Hornet’s carrier group. The Enterprise group, steaming as fast as possible, promised to reach the theater in time. By October 17, Nimitz knew the Japanese had seen Task Force 64. CINCPAC remained in doubt regarding locations of enemy fleet units, but he knew they were out there, and Ultra had provided some carrier positions and even radio call signs. On October 20, via COMINCH, Nimitz appealed to the British Admiralty for an Indian Ocean offensive to distract the Japanese from the Solomons.

The next day, in conjunction with new SOPAC chief Bull Halsey, the plans were set. The Enterprise (Task Force 16) and the Hornet (Task Force 17) would join on the twenty-fourth as Task Force 61 under Rear Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, and sweep north of the Santa Cruz islands, on the flank of any approaching Japanese fleet. At first CINCPAC foresaw the task force as being unable to act until the following day, but later it seemed they might be ready shortly after uniting. The battleships were sent on a midnight romp through Ironbottom Sound. No Japanese were found, so they moved to strengthen the carriers’ defenses. On the twenty-second a snooper saw the Kido Butai. Nimitz foresaw that for at least several weeks the Japanese would be able to throw more troops, planes, and ships into a battle than SOPAC. That could not be avoided. CINCPAC would apply calculated risk. “From all indications,” Nimitz’s war diary recorded on October 22, “the enemy seems about ready to start his long expected all out attack on Guadalcanal. The next three or four days are critical.”

In Truk lagoon on the morning of October 11, Yamamoto and Ugaki witnessed a momentous event from the fantail of the Yamato. Admiral Nagumo’s ships raised anchor and gingerly began their egress. Dark gray warships disappeared beyond the coral reefs of Truk’s north channel. After lunch the towering battleships of Admiral Kondo’s fleet, with Kakuta’s Carrier Division 2, departed south-side. Yamamoto, so sensitive of late, had begun micromanaging, questioning details. One big one was that the operations plan did not cover what to do in case of failure. Ugaki justified that with the comment that the fleet could not afford to fail. Everything had been done to ensure victory. Now was the time. The determined reinforcement program had put major Army units on Guadalcanal, and Navy efforts were near to suppressing Henderson Field. The day after the fleet sailed, Seventeenth Army chief of staff General Miyazaki and Navy staff officers Genda and Ohmae came up from Rabaul to plead for a battleship bombardment of Cactus. They were startled to learn one had already been laid on and was about to occur. Victory—that had a nice ring, rolled off the tongue easily, and it seemed close.

But Imperial Navy doctrine could be an obstacle. Under Yamamoto’s plan, Nagumo’s Striking Force of carriers would sail alongside Kondo’s battleships and cruisers of the Advance Force. Japanese doctrine accorded primacy to battleships, making Vice Admiral Kondo the overall commander. There were many aspects of carrier employment that would seem peculiar to a surface warfare specialist, and Kondo Nobutake had no experience of aeronaval operations. This might prevent success.

The fleet command was aware of the problem. Admiral Hara Chuichi had encountered it at Coral Sea and Eastern Solomons. After the second action Ugaki had Hara in for a long talk. Distilling his experiences, Hara sensitized Ugaki to the dangers in traditional doctrine. Though Hara sailed now as a cruiser commander, his contribution had been helpful. In the course of planning this operation, Ugaki brought Kondo and Nagumo together several times. The two were Etajima classmates and friends, so they were inclined to cooperate. But the reticent Nagumo was not the man to educate Kondo, gracious as he was, in carrier operations. That role fell to Third Fleet chief of staff Kusaka Ryunosuke, who had known Kondo since they had been boys in middle school together. Before leaving Truk, Kusaka coached Kondo on the finer points of aircraft use, and he induced the force commander to agree that in matters involving carriers, Nagumo would exercise control.

So the fleet went to sea. Vice Admiral Kondo maneuvered in the waters northeast of the Solomons. By night they steamed south to attain favorable dawn launch positions. During the day they would turn north and head toward Truk—if battle came, the Japanese wanted to be headed for safety, not destruction. This cautious approach disgusted many. In the screen, Commander Hara Tameichi on his destroyer Amatsukazi was among those discomfited by the seeming reluctance to close with the enemy. It bothered Yamamoto too. He had imagined an aggressive sortie beyond the Solomons into the Coral Sea, cutting through Torpedo Junction to isolate Guadalcanal. That would have forced the Allies into the open to restore communications. As Combined Fleet saw Kido Butai diverge, Ugaki nudged Kondo and Nagumo to adopt a forward-leaning posture. But neither Ugaki nor Yamamoto made this a direct order.

Rear Admiral Kusaka counseled caution. Kusaka could not escape feeling the American carriers, as at Midway, would appear on Nagumo’s flank. A sortie into the Coral Sea invited that. Kusaka was determined not to take the risk until the enemy carriers were accounted for. In the Imperial Navy, chiefs of staff had great power, and Kusaka used his to shield Nagumo from the complaints of inaction. When a new staffer aboard flagship Shokaku asked why the fleet did not stop this indecisive to-ing and fro-ing, Kusaka told him off, saying he was still an amateur at battle. The staff chief used the example of the sumo wrestler, who repeatedly left the fight to get salt to improve his grip, an act known as shikari. The fleet was doing shikari.

Kusaka fended off Ugaki as well. But as the days passed without action, morale suffered. The surface fleet was engaging the enemy. The Army, supposedly, was fighting. The Kido Butai did nothing. There were two key questions: the Army’s attack and the location of Allied fleets. Actually Hyakutake’s troops were still cutting their way through the jungle, struggling to reach assault positions. They literally hacked the “Maruyama Trail,” named for the leader of the Sendai Division, through the harsh land. The date of the Seventeenth Army attack was postponed once, then again. General Hyakutake pleaded insuperable difficulties. At Truk, Admiral Ugaki complained that the Army did not understand that postponements of a day here and there, of little consequence to a soldier, were serious for a fleet burning oil and wearing its ships. Delay pressed against operational limits. Had the Army kept its promises, the naval battle would have occurred before the arrival of U.S. carrier Enterprise, affording the Japanese overwhelming superiority. Aboard Amatsukaze, Commander Hara recalled “waiting impatiently,” a Navy that “stamped its feet in disgust.”

Intelligence on the Allied fleet posed the other big headache. The Imperial Navy had an inkling of new Allied forces. The Owada Communications Group had reported a task force leaving Pearl Harbor in mid-October. Ready to inform the Japanese was a low-grade aviation codebook captured from a U.S. torpedo bomber downed at Shortland on October 3. The first concrete information came ten days later, when a Chitose floatplane spotted a carrier and a battleship through a hole in the clouds. Also that day, Lieutenant Commander Nagai Takeo’s I-7 sent a floatplane over the harbor at Espíritu Santo at dawn, determining that there were no U.S. carriers there. Traffic on Japanese direction finding and intelligence radio nets spiked, especially on Rabaul circuits, something Allied codebreakers noticed. On the fourteenth Nagumo’s combat air patrol shot down an Allied scout. The Kido Butai (the text will use this term for all the Kondo-Nagumo forces for the moment) went looking for American carriers on its run south next day and found nothing but a tug towing a fuel barge toward Cactus. There had been an Allied convoy, but SOPAC had recalled it.

Continuing this shadow sumo bout, Japanese codebreakers recorded a high volume of Allied operational traffic, and on October 16, Rabaul added at least a dozen radio fixes on Allied ships. Aerial searches revealed a battleship group and a carrier force. With Nagumo out of position, the Eleventh Air Fleet sent out two attack units that encountered nothing but a tanker, which they hit but could not sink. Submarines supplied numerous sighting reports, establishing that Allied battleships were steaming south of Cactus. A few days later, Lieutenant Commander Tanabe Yahachi of the I-176 got close enough to attack, and his torpedoes put the U.S. cruiser Chester out of action for more than a year.

At the initiative of Kusaka Ryunosuke, the fleet tried another ploy to locate the American carriers. Kusaka imagined them lurking at the edge of Torpedo Junction. He convinced Nagumo to conduct a special search using the heavy cruisers Tone and Chikuma of Rear Admiral Hara’s Cruiser Division 8. These had been designed specifically as scout vessels. Carrying five floatplanes and capable of supporting more, they were ideal for work with the Kido Butai. Indeed, these cruisers had been sailing with Nagumo since Pearl Harbor. Hara had commanded carriers and knew their habits and workday cycles. For this operation his cruisers were with Abe Hiroaki’s Vanguard Force, still part of Nagumo’s command. On October 19, the Japanese carrier boss set Hara on a dash forward to the Santa Cruz islands. The Tone, screened by a single destroyer, sent aerial scouts to search. They found nothing. Admiral Abe recalled Hara when an Emily patrol bomber from Jaluit sighted a U.S. carrier near Nouméa. A few days later the Chikuma repeated the exercise in an easterly direction. Again no result.

Meanwhile the Japanese scouted Nouméa on October 19 with a floatplane from Lieutenant Commander Kobayashi Hajime’s I-19. No American carriers there. I-boats and air searches sighted battleships and cruisers but not carriers. Japanese intelligence circuits went wild, according to Allied monitors. By October 22, the Allies knew the Japanese were recording and tracking their radio call signs, and a couple of days later reported that the Imperial Navy had installed and was operating a radio direction finder on Guadalcanal itself.

The South Pacific cruise took its toll on the Imperial fleet. By October 17, Admiral Ugaki worried that the Kido Butai, running short of fuel, would be unable to maneuver. As an emergency measure one of Kondo’s tankers, emptied by the fleet, took half the oil from each of battleships Yamato and Mutsu at Truk and, after topping off from another vessel, went back out. The Japanese suffered their first important loss that day, in Kakuta’s Carrier Division 2, when a fire broke out in the generator room of his flagship, Captain Beppu Akitomo’s aircraft carrier Hiyo. Damage control extinguished the blaze, but Commander Matoba Shigehiro, Hiyo’s chief engineer, thereafter could not produce more than sixteen knots, hardly enough for a fleet engagement. Hiyo stayed in formation for the moment, but with growing strain on Matoba’s engines, on October 22 she blew out a condenser, cutting steam to some boilers. Admiral Kakuta shifted his flag to Captain Okada Tametsugu’s Junyo. Lieutenant Kaneko Tadashi led half of Hiyo’s planes to Buin, while the rest crowded onto Junyo. Escorted by destroyers, Beppu sailed Hiyo to Truk at her best speed, six knots. This loss reduced Japanese strength even before the battle.

The quandary continued. On October 22, an I-boat surfaced off Espíritu Santo before dawn and treated the SOPAC base to a rare harassing bombardment. Part of the Kido Butai refueled on October 24. In his cabin on the Shokaku, even Nagumo Chuichi chaffed. Hara Tameichi relates this scene: Puzzling over the assorted sighting reports and an American news story that mentioned expectations for imminent battle in the South Pacific, Nagumo spoke to his senior staff officer, Commander Takada Toshitane. What to do? Takada mentioned the high level of radio emissions from Allied submarines and aircraft. Nagumo asked for his chief of staff. Kusaka reported on the progress of refueling. Nagumo ordered him, once the oilers had finished, to inform the fleet that major battle impended.

A similar conversation took place on Kakuta’s flagship. Commander Okumiya Masatake, the admiral’s senior staff officer, drew attention to the date October 27—Navy Day in the United States (today annual naval festivities are part of Armed Forces Day, at that time Navy Day, dreamed up by active officers but enshrined in 1922 by the Navy League of the United States), which was celebrated on the birthday of Theodore Roosevelt, the father of the “Great White Fleet.” In conjunction with the expectations expressed in the American press, it seemed SOPAC might engage that day.

Back on the Shokaku, Commander Takada, no doubt aware of Admiral Kusaka’s views, suggested consulting Combined Fleet. Kusaka assented, but, after a few moments’ thought, turned the idea on its head, sending a dispatch that warned of a trap and recommended halting the fleet until the Army captured Henderson Field. He mentioned the idea of rescheduling to October 27. Ugaki’s return message was direct: “STRIKING FORCE WILL PROCEED QUICKLY TO THE ENEMY DIRECTION. THE OPERATION ORDERS STAND, WITHOUT CHANGE.”

Admiral Ugaki’s version of this story appears in his diary. Kusaka’s dispatch reached Yamato in the evening. Though sent before noon, it was delayed in retransmission by a relay vessel. Ugaki acknowledged that October 27 might be a better moment for battle, but the Kido Butai’s failure to attain assigned positions could endanger the entire plan. Combined Fleet sent the Army a different message declaring that if the offensive did not begin immediately, lack of fuel would require the Navy’s withdrawal. But Ugaki felt Kusaka’s eleventh-hour démarche outrageous and arbitrary. His urgent reply: “THIS COMMAND HAS THE WHOLE RESPONSIBILITY. DO NOT HESITATE OR WAVER!”

Everything hinged on the Japanese Army. Admiral Yamamoto recognized that. As they stood together on Yamato’s upper deck, he told Ugaki that the Army chief of staff must be more anxious for victory than anyone. Only the Army could actually capture Henderson Field. American bombardments and air attacks had robbed Seventeenth Army of about a third of the supplies from the high-speed convoy, and the remainder, those to sustain the fight, had to be carried by the men themselves. General Hyakutake split the Army into two detachments under his overall control. To attack along the coast, around the Matanikau, would be Major General Sumiyoshi Tadashi, the Army’s artillery commander, with two infantry regiments plus the tanks and guns. Inland, under tactical command of Sendai Division boss Lieutenant General Maruyama, the other group would make the direct attack toward Henderson Field.

The difficulties of the land slowed preparations. Except for Sumiyoshi’s men along the Matanikau, in increasingly well-known terrain, the Japanese were largely navigating by compass bearing through thick jungle. No one had surveyed Guadalcanal or produced accurate maps. And the soldiers starved. Hungry men had trouble hacking their way through the undergrowth. Rough country plus rudimentary navigation meant errors in reckoning positions. Thus Hyakutake’s postponements. To divert the Americans and keep to some semblance of the schedule, General Sumiyoshi ordered one regiment across the Matanikau to probe the Marine defenses. The unfortunate Colonel Oka led this maneuver, never intended as the main assault. On October 23 his troops tried to attack but bogged down in the jungle. At Truk, Admiral Ugaki, learning of Oka’s failure, reflected on the dishonor the colonel heaped on his regiment’s flag. Sumiyoshi’s other regiment, with the tanks, was to attack across the river as part of the main offensive, most recently scheduled that very day. But General Sumiyoshi was prostrated with malaria, and his staff never circulated the postponement notice. The attack along the Matanikau went ahead on the original schedule. It gained little—though Marine General Vandegrift indeed turned his eyes there. The Marines crushed the developing attack with 6,000 rounds of artillery fire.

Hyakutake’s main attack by Maruyama’s force had been set for nighttime. But the tactical commander found himself short of the assembly area. Chronic neuralgia also impaired Maruyama’s faculties. He pleaded for another postponement. The troops finally swung into action on October 24. This operational group divided into two wings plus a reserve. Each wing, one of them led by General Kawaguchi, comprised a reinforced regiment. Maruyama kept another regiment in reserve. They would attack up Bloody Ridge and to its right.

In U.S. Marine lore, that night through the next went down as “Dugout Sunday.” Vandegrift had made preparations too, and his forces were well fortified. With the addition of the U.S. Army 164th Infantry, Vandegrift was slightly superior in men, considerably advantaged in artillery, and now better supplied. One Japanese officer ruefully told comrades that for every shell loosed against the Americans, they answered with a hundred.

The redoubtable Chesty Puller and his battalion had redeployed to the sector Maruyama attacked. Vandegrift sent them a battalion of the green 164th Infantry, making up for a Marine unit hastily pulled away to the Matanikau. The Japanese went in. Unlike in the Matanikau sector, Maruyama had but a single mortar battalion to support him. Kawaguchi’s column wandered into the jungle and hardly participated. A fulminating Maruyama relieved Kawaguchi. Colonel Nakaguma Nomasu’s regiment bore the brunt of the fight. Their only chance lay in the fact that Puller had had to extend his line to take over the front vacated by the absent Marine battalion, and that Marine artillery had expended most of its ammunition in the Matanikau action. A spirited attack began after midnight on October 25. Puller slowly fed the 164th Infantry reinforcements into his 1/7 Marine line as the fighting progressed. Nakaguma made only a few shallow penetrations. The Japanese left almost 1,000 bodies in the barbed wire.

Following Maruyama’s attack, the Army notified the Navy that Henderson Field had been captured. Carrier planes were sent to verify this. Soon afterward, Lieutenant Funashi reported from his observation post that battle raged in Henderson’s vicinity. The situation remained obscure. Based on General Hyakutake’s instructions and the original capture claims, Admiral Mikawa initiated what was to have been the coup de grâce of the offensive—a variety of actions by several units. One was the landing of a unit called the Koli Detachment to complete the conquest of the airfields from the beach side. A group of three destroyers would also deliver fuel and bombs to the newly captured Henderson Field to enable Japanese planes to fly from it immediately. A formation of tin cans led by a light cruiser would interdict Guadalcanal waters from the west, while another did so to the east. Mikawa recalled them when aerial observers determined that the Americans still held Henderson.

But the Army begged for a naval bombardment, and Mikawa sent back three destroyers, hoping a sudden shelling might stun the Americans into relinquishing their hold. Combined Fleet ordered Rear Admiral Takama Tamotsu’s group, with light cruiser Yura and five destroyers, to back this sally, unnecessary since the Destroyer Squadron 4 leader had already reversed course for that very purpose. After daybreak, the Navy observation post reported a U.S. light cruiser in the anchorage. Two World War I–vintage tin cans, not a cruiser, actually lay off Tulagi, where they had delivered fuel and torpedoes for the PT boats and towed in four new craft. They cleared harbor once they saw the first Japanese destroyers, which gave chase and inflicted some damage. The Japanese then nearly ran down a pair of U.S. naval auxiliaries before returning to their bombardment mission. At that point shore batteries and the Cactus Air Force intervened, driving off the destroyers.

Cactus airplanes caught up to Yura. When the first bomb hit, Lieutenant Kamimura Arashi was at the engineering control station, his body vibrating as the engines strained into a high-speed turn. Kamimura staggered with a direct hit on Yura’s number three boiler room. Men in the other two were wounded by fragments. The Yura lost power, fires broke out; then more hits followed. Captain Sato Shiro ordered, “Abandon ship.” He signaled other vessels to fight to the end. Sato refused to leave, tying himself to Yura’s bridge. The sailors evacuated to destroyers. While standard accounts state the Yura had to be scuttled, Lieutenant Kamimura believed the cruiser was breaking up as her crew left.

Through the afternoon the Cactus Air Force beat off renewed JNAF attacks with more losses on both sides. But that was only a prelude for the ground battle, when General Maruyama again hit Vandegrift’s perimeter, this time with a better-prepared night attack. Chesty Puller’s Marines and the U.S. Army infantry had by now taken separate sectors, with Puller on Bloody Ridge. Maruyama hit both and committed his reserve, whose commander, as well as Maruyama’s tactical leader, Major General Nasu Yumio, were killed. The weight of the Japanese attack fell on the newly blooded 3/164, which acquitted itself well. Meanwhile, the wing formerly led by General Kawaguchi again failed to engage. On the Matanikau front, Colonel Oka launched his troops against the 2/7 Marines and succeeded in taking one hill, but they were ejected by Marine counterattacks. Although General Maruyama claimed he had penetrated the U.S. perimeter, that was an illusory result. Staff officers, including Colonel Tsuji, told Seventeenth Army the attack had failed. General Hyakutake ordered a stand-down on the morning of October 26. The Army offensive had collapsed. Navy observers reconfirmed the American hold on Henderson at 5:15 a.m. But by that time the Imperial Navy was embroiled in its own battle.

Rear Admiral Kusaka discounted Combined Fleet’s peremptory orders. In his view Ugaki was a blowhard with no battle experience, a neophyte not worth listening to. The fleet held to its routine, making the usual run south on the night of October 24. Frustration increased. In the morning Nagumo detached Rear Admiral Abe Hiroaki’s Vanguard Force to take station ahead of the carriers. Abe had battleships Hiei and Kirishima, Cruiser Divisions 7 and 8, and a destroyer squadron. Shortly after 10:00 a.m., a U.S. scout discovered the Kido Butai in position roughly 230 miles northeast of Henderson. Kusaka heard that a snooper had been downed by patrol fighters. Nagumo turned north. Carrier planes, then the Navy observation post, advised that the Americans were still at Henderson, affirmed by the bombing that cost the Yura. Unknown to Nagumo, Kinkaid had actually sent an Enterprise strike wave against him that afternoon, but with Kido Butai’s turnaway, and no tracking data, the planes found empty sea. They returned in the dark. A Wildcat plus seven TBFs and SBDs, out of gas, had to ditch.

There was no escaping Combined Fleet’s constant prodding, however. Late that afternoon, alone in the flag plot on the Shokaku, Nagumo had another heated exchange with his chief of staff. Kido Butai’s commander was ready to fight. Kusaka still advised caution. The same conversation had occurred repeatedly before staff. Admiral Nagumo had had enough of that unpleasantness. The time had come to attack without remorse. Ugaki’s latest dispatch could not be ignored. The carriers would advance. Nagumo wanted his chief of staff to decide to head south.

“I admit I’ve objected to your suggestions,” Kusaka replied, “but you are the commander and must make the final decisions.” Then the chief of staff repeated his litany: The American fleet had yet to be found; now that they themselves had been discovered, the B-17s from Espíritu Santo would surely reacquire them. If they went south they must expect things to happen. Besides, Kusaka continued, as chief of staff his place was merely to assist. Only the two men were present, staring each other down, and Nagumo Chuichi did not survive the war. Kusaka attests that Nagumo insisted. The chief of staff gave in: “It’s your battle. If you really want to head south, I’ll go along with your verdict.”

In the gathering dusk of October 25, the Kido Butai came about and set a southerly course at twenty knots. It was one of those enchanting South Pacific evenings, the night warm and the moon shining. At 9:18 p.m. the fleet received Yamamoto’s latest operations order, noting the Army’s plan to storm Henderson Field, forecasting a high probability that Allied naval forces would appear northeast of the Solomons, directing that the enemy be destroyed.