COOKING TEACHER AND AUTHOR

Highland Park, Los Angeles

BUCKWHEAT FLOUR, ALL-PURPOSE FLOUR, tapioca starch, water. By all standards, it’s an unremarkable list of individual ingredients. But in the hands of Sonoko—educator, author, and consummate artisan soba noodle maker—the succinct recipe has never been an impediment to her imagination. “Every time I make noodles, they come out a little different. The ingredients are always the same, but there are numerous variables involved. Even the temperature of the hands can change the outcome,” she says, glancing up for a beat before returning to the rhythm of kneading. When we first began hosting creative workshops at Poketo, we knew we wanted to expand upon the traditional definition of an artist to include a wider range of talents, but all sharing a dedication to creativity. In this way, Sonoko embodies an artist who just happens to work in an edible medium.

Angie first caught wind of Sonoko in 2008. Back then, Sonoko was just beginning to teach workshops at our neighborhood organic grocer, utilizing the skills she learned while studying soba-making in Japan. Sonoko had left a decades-long career as a film producer to become a writer and teacher, introducing soba noodles and the technique for making them to an entirely new audience in Los Angeles. We reached out to Sonoko years later with the proposal of hosting a soba-making class at Poketo. She agreed after attending one of our other workshops, appreciating the energy and community, and her own workshop sold out in a matter of days.

Standing shoulder to shoulder with attendees, we were mesmerized by Sonoko’s confident and precise technique, following her guidance to transform our four ingredients into springy and complex noodles. Genuine buckwheat-flour soba noodles are earthy and texturally satisfying, and taste absolutely nothing like the packaged “soba” noodles found at the supermarket. “That’s just flour with food coloring added,” she says.

Sonoko is already sifting flour when we first enter her home, located in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Highland Park. She’s readying a snack of plain soba accompanied by a dipping sauce of seasoned stock we will soon sit down to share. It is a simple meal, prepared with the measured efficiency of someone who could do this with her eyes closed. So it is somewhat ironic that the modest method unfolding before our eyes happens upon a grandiose stage—a table built by her husband, accomplished artist Katsuhisa Sakai. The table was tailored specifically to Sonoko’s dimensions and movements, a platform of purpose and process for making and teaching. A shelf underneath offers a place for her to lodge her collection of bowls, knives, baskets, brushes, and rollers, a cast of tools that magically appears throughout the preparation we’ll witness. The table’s combination of form and function preludes the rest of the couple’s life inside these walls.

“This table is large, but it can be moved easily for my workshops. A lot of our furniture is made to be moved around as needed,” she explains, noting that hosting classrooms and workshops regularly within your own home requires an adaptable interior, if not an adaptive personality.

The entire house breathes with thoughtful purpose. Their work requires organization, with tidy collections of bowls, cookware, and jars of fermented foods that will eventually make their way into Sonoko’s cooking. What seems like a handmade lantern floating over the dining room table turns out to be a salvaged lampshade patched and turned upside down, an example of the couple’s devotion to extending the life of any object invited into their home. Fermentation jars, books, and a few objects of sentimental history congregate in corners of the house. “I was able to make a place for some sentimental objects I’ve kept over the years by giving them newfound purpose,” Sonoko says.

Inside this Southern California home, light and negative space operate as quiet partners with the couple’s spare collection of furniture. The overall effect isn’t austere, but one where it feels life is enjoyed without distraction. The few furniture pieces within their home seem to have arisen from the floor as naturally as geological formations. Warm sunlight enters the front of the home through their westward-facing windows, while the rooms in the back harbor a sanctuary of shade.

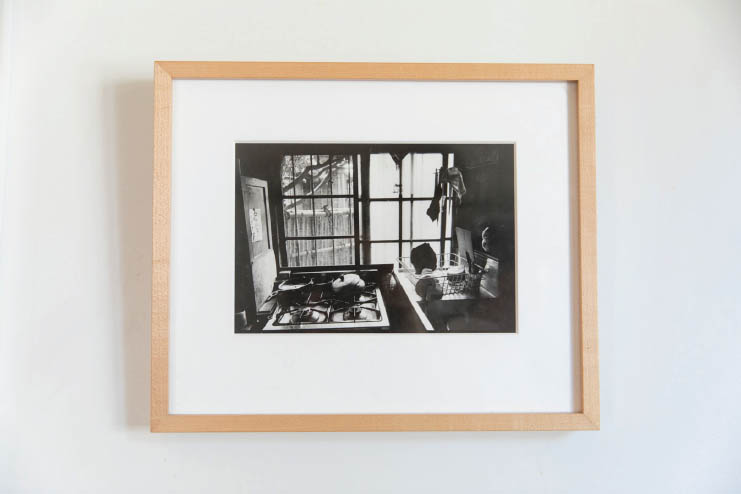

This is not to say the house is barren. Sonoko’s insistence for preserving memory keeps the home rooted in the realm of the domestic rather than the monastic. In the kitchen a lone black-and-white photograph of her grandmother’s Japanese kitchen adorns the wall, afforded a special place so Sonoko can always revisit the memory and be guided by it. “Look carefully and you can see I’ve arranged my kitchen to look as close to hers as I can. I have even placed my tools hanging the same way she did . . . I’m hoping to re-create the view out the window, too,” she says, looking into their courtyard where several of Katsuhisa’s statues stand sentry along a leaf-covered path leading to the backyard. “This house is a work in progress. There’s still so much to do. I have dreams for a garden soon.”

We asked Sonoko to give us a favorite, everyday recipe. Miso soup is something she makes for herself every morning. What a nourishing and warm way to start each day. This recipe is simple enough for anyone and so delicious.