“Dead to Sin” and “Alive to God” (6:1–14)

What Paul has said in 5:20 about grace increasing all the more where sin increased might lead readers to the wrong conclusion. They might think that God’s promise to meet sin with his grace means that sin does not matter—that Christians, because they are ruled by grace, need no longer concern themselves with sin. Like the seasoned preacher that he is, Paul anticipates this incorrect inference and heads it off immediately in chapter 6.

What shall we say, then? (6:1). As we noted in our comments on chapter 2, the question and answer style of writing that Paul frequently uses in Romans is similar to the ancient style of diatribe. In this case, however, he uses the style to teach Christians, not to debate with opponents of the faith. Scholars have shown that the diatribe style was often used in the ancient world in just this educational kind of setting.36

All of us who were baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death (6:3). Paul’s teaching that baptized believers become participants in Jesus’ death and resurrection (cf. 6:5) has led to a long and contentious search for the background that might have led him to this idea. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, many scholars, persuaded that Paul’s interpretation of Christ was deeply indebted to Greco-Roman influences, thought his conception of baptism into Christ’s death came from the so-called mystery religions. These religions, which adherents joined by undergoing a secret rite of initiation, or mystērion, sometimes offered people the opportunity to be mystically joined to a dying and rising god. Paul, it was thought, adopted this idea and applied it to the Christian’s union with Jesus in his death and resurrection through baptism. However, most scholars today don’t think that the mystery religions had much influence on the early Christians’ conception of Christ and his benefits. As A. J. M. Wedderburn has argued, it is improbable that Paul’s presentation of the Christian’s identification with Christ in his death and resurrection through baptism in Romans 6 has much to do with the mystery religions.37

What does inform Paul’s notion of the believer’s identification with Christ is his “second Adam Christology.” As we have seen, Romans 5 presents Adam as representative head of the human race. Because all people are represented in Adam, his sin can at the same time be the sin of all people. Now Paul, of course, presents Christ as a representative figure similar to Adam. He can, then, portray Christians dying with Christ and being buried with him because he thinks of believers participating in Christ’s acts of redemption. Baptism, as we will see, is Pauline shorthand in this text for the conversion experience.

Also debated is what Paul means by claiming that baptism is “into Christ Jesus.” Paul may simply be abbreviating the common formula “in the name of Christ/Jesus,” used several times in the New Testament in relationship to baptism (see Matt. 28:19; Acts 8:16; 19:5; cf. 1 Cor. 1:13, 15). But the “name” in the culture of that day represented the person himself or herself. Thus, this concept inevitably shades into the other idea, that Paul views believers as incorporated into Christ through baptism. At least one rabbinic text (b. Yebam. 45b) suggests that “wash in the name of” signifies being bound to the person in whose name one is washed.

“BAPTISMAL” POOL

A traditional Jewish purification bath (miqveh) discovered near Herod’s palace in Jericho.

We were therefore buried with him through baptism (6:4). An important concept in 6:4–8 is the notion that Christians were “with” Christ in his death/crucifixion (6:5, 6, 8), burial (6:4), and resurrection (6:5, 8). How are we to understand this “withness”? Many scholars appeal to the general religious notion of “mysticism” to explain the idea. The identification with a god who died and rose to new life each year (imitating the cycle of nature) in the mystery religions (see above) would be one example of such a mystical concept. But the notion of some kind of merging of personality between a person and a god was found in many ancient Near-Eastern religions as well.

The basic concept that informs Paul’s language here, however, should not be labeled “mysticism.” As we noted in our comments on 5:12–21, Paul’s teaching grows out of the Old Testament/Jewish notion of corporate solidarity. This notion is not properly “mystical,” since it does not posit any merging of personalities. The solidarity is judicial or forensic. This is particularly clear with respect to Adam, who is, of course, not a god but an individual human being, whose significance for others is as their representative. This notion carries over into Romans 6 and explains how Paul can claim that believers were “with” Christ in his death, burial, and resurrection. As Adam in his sin represents all people, so Christ in his redemptive work represents people. Death, burial, and resurrection are singled out here because these three events were part of the core early Christian tradition about Christ’s redemptive work. Note, for example, 1 Corinthians 15:3–4: “For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures.”

In order that . . . we too may live a new life (6:4). A literal translation would be: “in order that . . . we too may walk in newness of life.” Paul’s use of the word “walk” to describe a person’s lifestyle reflects a widespread Jewish metaphor (using the Hebrew word hlk). See, for example, Deuteronomy 26:17: “You have declared this day that the LORD is your God and that you will walk in his ways, that you will keep his decrees, commands and laws, and that you will obey him.”

If we have been united with him like this in his death, we will certainly also be united with him in his resurrection (6:5). “United with” comes from a verb that means “grow together” (symphyō) and is often used in horticulture. Many interpreters, therefore, conclude that Paul may be alluding to Jesus’ famous illustration of the vine and the branches (John 15). However, the word is used in many contexts, most of them not horticultural. We have no reason to think that this particular connotation of the word would have been in Paul’s mind at this point.

Our old self was crucified with him (6:6). Paul uses the language of the “old self” or “old man” also in Ephesians 4:22–24 and Colossians 3:9–11. In both of these, the “old self,” which Christians “put off,” is contrasted with the “new self,” which they have put on (Col. 3) or are to put on (Eph. 4). Modern interpreters often give the imagery an individualistic interpretation, as if the “old self” were the believer’s sinful “nature” and the “new self” the renewed nature given at conversion. But Paul’s idea is probably more corporate than this. We must again remember what he said about Adam’s representative significance in chapter 5. With this notion present in the context, we are probably right to think of the “old self” as essentially Adam himself. Christ is then the “new self” (see Eph. 2:15; 4:13). What is crucified with Christ, then, is not some part, or nature, of us, but, as J. R. W. Stott puts it, “the whole of me as I was before I was converted.”38 When a person comes to Christ, that person is no longer under the domination of (though still influenced by) the nexus of sin and death brought into the world by Adam.

Anyone who has died has been freed from sin (6:7). “Freed [from]” actually translates the verb that is regularly translated “justify” (dikaioō). Many commentators think this translation should be preserved here. If so, then this verse is claiming that the believer’s freedom from sin’s power (6:6) is based on (note the “because” at the beginning of 6:7) the believer’s justification (from sin’s penalty). This idea may be theologically quite acceptable. But the NIV rendering has a lot to be said for it. Only here in his writings does Paul use the preposition “from” (apo) after the verb “justify” (though cf. Acts 13:38). More important, Paul may well be reflecting here a Jewish tradition, preserved in b. Šabb. 151b: “When a man is dead he is freed from fulfilling the law.”39

The death he died, he died to sin once for all (6:10). The believer’s death “to sin” is the ruling idea of this paragraph (see 6:2). It is a metaphor Paul uses to indicate the believer’s complete break with the domination or mastery of sin. Being “dead to sin” means that Christians are no longer “slaves to sin” (6:6); sin is no longer our master (6:14). But why would Christ have had to “die to sin,” as 6:10 claims? Some commentators think Paul may be using the metaphor in a different way here, to depict the redemptive benefits of Christ’s death on our behalf. But we can maintain the same basic significance of the metaphor when we remember that Paul is writing in the context of his ruling “two-age” salvation-historical scheme (see comments on 5:21). In his incarnation, Christ took on our humanity and entered into the present evil age. Sin rules this age, and so Christ was subject to its power throughout his earthly life. To be sure, he never succumbed to that power and actually sinned. But he did need to be released from its power; and his death was that release. The main line of Paul’s argument in these verses thus becomes clear:

• Christ died to sin (6:10).

• We died with Christ (6:5, 6, 8).

• Therefore, we have died to sin (6:2).

In Christ Jesus (6:11). Paul’s salvation-historical conception, rooted in Jewish apocalyptic, can again explain his claim that believers are “in” Christ. This idea, widespread in his letters, is again often thought to reflect ancient religious mystical notions. A. Deissmann, who popularized the notion in the early 1900s, argued that Paul viewed Christ as the “medium” or “ether” in which the Christian lives. But such a conception tends to depersonalize Christ and therefore runs counter to New Testament views of Jesus. A better explanation is to refer again to Paul’s belief that Christ is the representative head of the new age of salvation. He incorporates within himself all who belong to him by faith. To be “in Christ,” then, means to be identified with Christ as our representative and to have all the benefits he has won in his redemptive work applied to us.40

You are not under law, but under grace (6:14). Failure to appreciate the background of Paul’s teaching can lead casual readers of Romans to misunderstand this assertion badly. Some might think that Paul proclaims believers to be free from any code of ethics at all. Those who have some knowledge of the history of theology might conclude that Paul proclaims the freedom of the believer from any divine commands—“law” in the sense the word is used in Lutheran theology, as the contrast to the gospel.

But, as we have seen earlier (see comments on 2:12), “law” (nomos) in Paul, a first-century Jew, almost always refers to the Mosaic law, the Torah. Paul is not claiming that believers are free from any divine commands (such as those we find in the teaching of Jesus or the New Testament letters). What he means is that believers are no longer bound to the Mosaic law. A new era in God’s plan of salvation has dawned, an era in which God’s eschatological grace is being poured out. With the coming of this new era, the old era has ceased to be the one to which we belong. The law of Moses was part of that old era. (Paul develops this argument in great detail in Gal. 3:15–4:7.) Paul’s statement here is similar, then, to John’s claim: “The law was given through Moses; grace and truth came through Jesus Christ” (John 1:17).

Freed from Sin’s Power to Serve Righteousness (6:15–23)

Paul’s focus in 6:1–14 has been on the negative: Believers are no longer slaves of sin (6:6). In 6:15–23, he broadens the perspective by including the positive side as well: Set free from sin, believers are now slaves of righteousness and of God.

Don’t you know that when you offer yourselves to someone to obey him as slaves, you are slaves to the one you obey (6:16). Slavery was one of the best-known institutions in the ancient world. Almost 35–40 percent of the inhabitants of Rome and the peninsula of Italy in the first century were slaves; and the situation in the provinces may have been comparable.41 So Paul’s analogy would have been one that all his readers could immediately have identified with. Making the analogy even more exact is the fact that people in the ancient world could sell themselves into slavery (e.g., to avoid a ruinous debt).42 Similarly, Paul suggests, believers who constantly obey sin rather than God might find themselves to be slaves of sin again, doomed to eternal death.

You have been set free from sin and have become slaves to righteousness (6:18). Modern people, especially in the West, prize their autonomy. As heirs of the humanism of the Enlightenment, they assume that the noblest human being is the one who is subject to nothing but his or her own rational considerations. Ancient people, however, had a much stronger belief in the degree to which all human beings were under the control of outside powers—whether they be gods, the stars, or fate in general. The biblical writers certainly share this conviction. Nowhere in this paragraph does Paul suggest a person might not be a slave of something. Either he or she is dominated by sin or by righteousness and God—there is no middle ground. Jesus reflects the same perspective when he claims that “no one can serve two masters. Either he will hate the one and love the other, or he will be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve both God and Money” (Matt. 6:24).

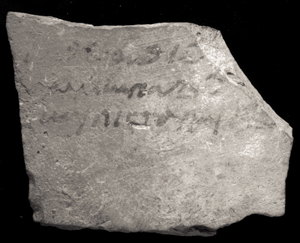

RECEIPT FOR DELIVERY OF A SLAVE

This receipt is written on a pottery shard (ostracon) discovered in Egypt.

Offer them in slavery to righteousness leading to holiness (6:19). “Holiness” (which suggests the state of being holy) can also be translated “sanctification” (which suggests the process of becoming holy). In either case, Paul picks up the imagery from the Old Testament, where the root qds is widely used to denote the idea of being “set apart” from the world for the service of the Lord. As Christians give themselves in slavery to righteousness, they will progress further and further on the path of becoming different from the world and closer to the Lord’s own holiness.

The wages of sin is death (6:23). “Wages” translates opsōnia, a word that means “provisions,” but which is often used of money paid for services rendered. It was particularly applied to the pay given to soldiers (all three uses in the LXX have this sense [1 Esd. 4:56; 1 Macc. 3:28; 14:32]). The specific imagery in this verse, therefore, might be sin, as a commanding officer, paying a wage to his soldiers.