God’s Children—Not Slaves (4:1–7)

This section shows what inheritance means. The contrast is a direct one between “slaves” and “sons” (4:7), and so what believers are as inheritors. Roman society—with its institution of slavery and its family life, where children had no rights or little significance until they grew up to adulthood—is reflected here. Paul uses this framework to argue for spiritual applications, which we may tabulate: (1) Childhood is a time under control (4:2); (2) it is akin to slavery (4:3); (3) yet it holds the promise of reaching adulthood, just as some slaves hoped to be set free by manumission (see earlier on 3:13).

“Abba, Father” (4:6). Abba is Jesus’ familiar name for God as “dear father”(Mark 14:32–39; Luke 11:2–4).

No longer a slave, but a son (4:7). (1) Slavery induces fear and can represent the human condition under the power of bad religion, called “the basic principles of the world” (4:3). Here, however, it is more likely a reference to star worship. The cosmic “elements” were thought to control human beings and to lead to uncertainty about human fate, as 4:8–9 makes clear. (2) Slavery pictures men and women in bondage to sin and needing to be “redeemed.” This has happened in Christ’s coming and death (1:4; 3:13). (3) The outcome is a new life of “sonship,” enjoying our full inheritance (4:1, 5) and freedom as God’s children who know intimately the smile of their Parent.

Paul’s Expression of Concern (4:8–20)

Slaves to those who by nature are not gods (4:8). This is a clear indication that the Galatians were pagan before entering God’s family in Christ. Paul marvels (as he does at 1:6) that they should wish to revert to the slavery brought on by fear of cosmic powers—such as the star deities that once ruled their lives—by imposing a regime of observing “special days” when good luck may be expected for an enterprise (a typical sentiment of Greco-Roman religion with its recourse to magic, omens, and horoscope predictions). Their interest was in what “days” were good for business or travel or marriage and which “seasons” were favored by the gods to produce fertile ground or harvest yield.

Because of an illness that I first [or, on a former occasion] preached the gospel to you (4:13). Paul’s first visit to Galatia (in Acts 13–14) is the background here. He was evidently a sick person at that time and suffered a disfiguring or debilitating illness that could have made the Galatians reject him as the opposite of a divine messenger. Instead, they welcomed him as a person sent from God (like Hermes/Mercury in Acts 14:12) and obeyed the gospel call as if Christ himself were speaking.

HERMES

You welcomed me as if I were an angel of God (4:14). The surnaming of Paul as a “messenger [angelos] of God” combines the two cultural ideas of (1) Jewish representatives (Heb. seluḥim) of the synagogues of the Dispersion, charged to carry funds to Jerusalem, and (2) the Hellenistic depiction of a messenger of the gods, notably Hermes in the Homeric pantheon.50 A son of Zeus and the nymph Maia, Hermes played many roles, notably as a guide for divine children, leading them to safety, and as a psychopōpos, i.e., one who escorts souls to the underworld of Hades. But he is best known as a messenger god who is obedient to the king of the gods, Zeus, and executes his orders.

Torn out your eyes (4:15). Some take this to mean that Paul’s sickness was ophthalmic—possibly a migraine headache that affected his vision; this is why, perhaps, he had to write in large letters (6:11).

My dear children, for whom I am again in the pains of childbirth until Christ is formed in you (4:19). This sentence is a remarkable window into Paul’s pastoral care for his converts. He likens his role as a birth-mother undergoing labor to deliver her child. His goal as an apostle is to see people reflect the likeness of Christ (2 Cor. 3:18). Children were regarded in low esteem in Greco-Roman society.51 Paul’s more positive attitude is given in Colossians 3:18–4:1.

Two Women—Two Covenants (4:21–31)

Paul reverts to an argument from scriptural exegesis, employing an allegorical method familiar in Philo. In Abraham’s household two women lived uneasily together: Hagar (Gen. 16:5) and Sarah (21:2). Paul’s chief interest is with them as mothers of two children, Ishmael and Isaac. He develops two lines of descent and connects them to a spiritual/figurative meaning. This interpretation is based on his desire to show that only one son was “born as the result of a promise” (4:23) and that this line leads to freedom, not slavery (4:31). That is the key to Paul’s thought. We may note that he uses the term “covenant” to include both lines of development from Ishmael as well as Isaac, whereas in 3:15–16 he kept “covenant” to relate to promise, not law.

| Slavery | Freedom |

|---|---|

|

• Hagar was a slave woman |

• Sarah was a “free” wife |

|

• Ishmael, born of the flesh, a trademark of the Judaizers (6:13–14) |

|

|

• Mount Sinai, Jerusalem of the Judaizers (4:25), is a symbol of slavery |

• Mount Zion (4:26; Heb. 12:22) stands for joyous freedom (based on Isa. 54:1) |

|

• “Ishmael” is in slavery and opposes his brother |

• “Isaac” (Paul and his converts) suffers persecution (Gal. 6:12–13) |

|

• But the Judaizers are to be refused since Ishmael did not gain an inheritance (4:30) |

• Rather, Paul’s gospel connects believers with the “free woman” and the promise of liberty (4:31) |

The table above may help set out the issues as Paul sees them:52

Recent study of these verses has helped our understanding of Paul’s argument in introducing this extended allegory or illustration of Hagar and Sarah.53 The Jewish scribes used this story from Genesis to praise the line from Abraham/Sarah to Israel,54 but Paul’s purpose is different. The climax comes at 4:30, where he cites Genesis 21:10. The citation in this verse shapes his conclusion in answer to the question, “Are you not aware of what the law says?” (4:21).

The examples given of Hagar and Ishmael (who represent slavery and the life of servitude “under the law”) and Sarah and Isaac (who stand for the covenant of grace and freedom) are targeted at the Judaizers, who sought to impose legalism on Paul’s Gentile converts. Yet the conclusion in 4:30—“get rid of the slave woman and her son”—is not directed at Judaizers or Jews, but at the covenant of Sinai. The old covenant leads to bondage since it is based on “flesh” and not the Spirit. It belongs to the old order, not the new age of messianic salvation brought by Christ and endorsed by the Spirit.

Paul will develop this line of reasoning at length later when he writes 2 Corinthians 3:1–18. There the same conclusion is reached as in Galatians 4:31: “We are . . . children . . . of the free [one],” Christ Jesus, and we have a spiritual parentage, “the Jerusalem that is above [which] is free” (4:26), the mother of both believing Jews and Gentiles. Paul’s use of the figure of the holy city of Jerusalem to relate to a spiritual home, the church of God’s new creation, not any geographical or ethnic location, is to be noted, and is parallel with Hebrews 12:22 and Revelation 21:1–5.

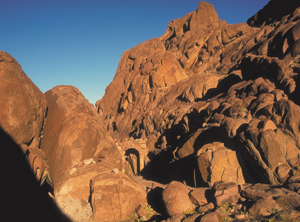

MOUNT SINAI