LESSON 2

What? Where? Who?

何?どこ?だれ?

Nani? Doko? Dare?

In this lesson you will learn how to identify people and things around you. You will learn many ways to refer to items, using the Japanese equivalent of the copular verb ‘to be.’

|

[cue 02-1] |

Basic Sentences

1. |

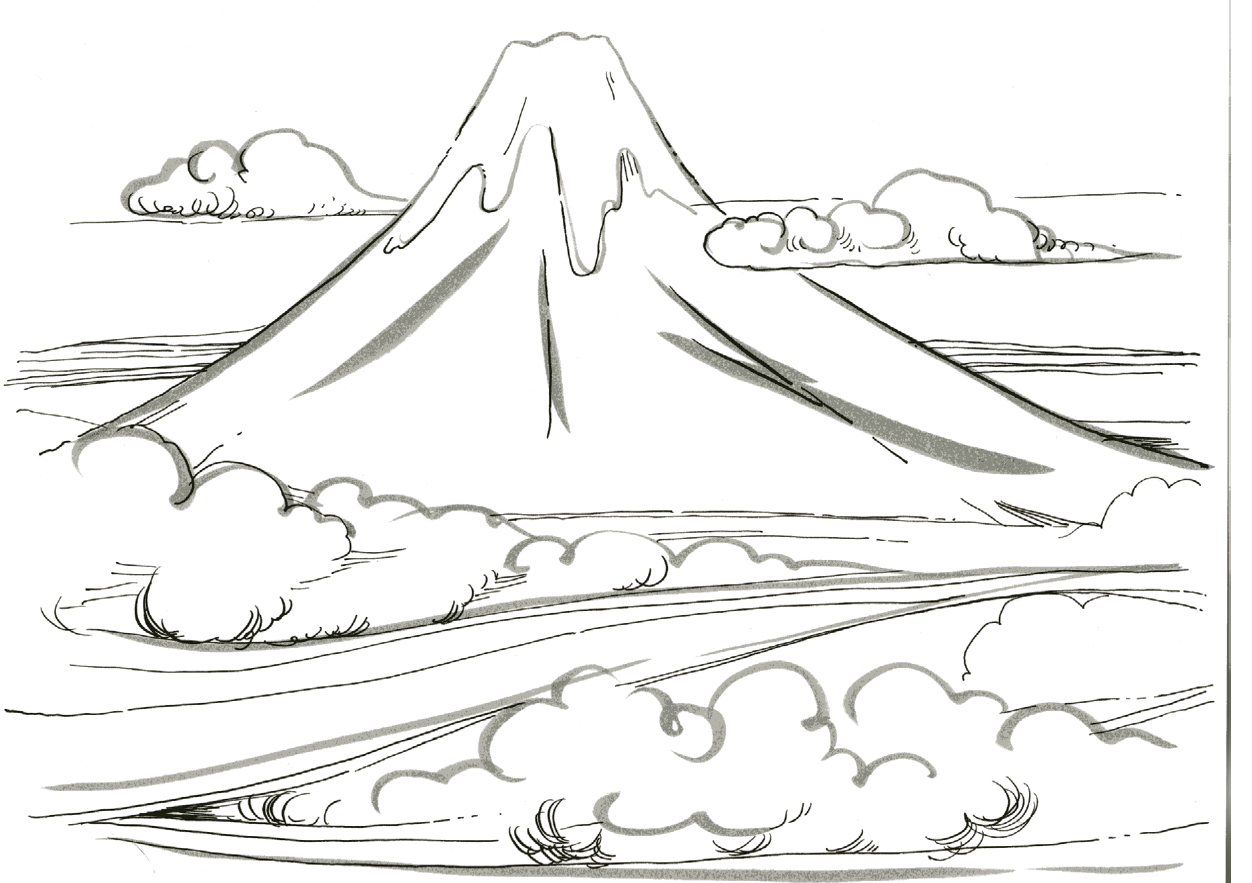

あれは富士山です。 Are wa Fujisan desu. That one over there is Mt. Fuji. |

|

2. |

「それは何ですか。」 “Sore wa nan desu ka.” “What is that (the thing you are holding)?” |

「これはカメラです。」 “Kore wa kamera desu.” “This is a camera.” |

3. |

「あの人はだれですか。」 “Ano hito wa dare desu ka.” “Who is that person?” |

「マイクさんです。マイクさんは 学生です。」 “Maiku-san desu. Maiku-san wa gakusei desu.” “He is Mike. Mike is a student.” |

4. |

「この傘はだれのですか。」 “Kono kasa wa dare no desu ka.” “Whose is this umbrella?” |

「それは私のです。」 “Sore wa watashi no desu.” “That’s mine.” |

5. |

「田中さんの傘はどれですか。」 “Tanaka-san no kasa wa dore desu ka.” “Which is Ms. Tanaka’s umbrella?” |

「私のはあれです。」 “Watashi no wa are desu.” “Mine is that one over there.” |

6. |

「銀行はどこですか。」 “Ginkō wa doko desu ka.” “Where is the bank?” |

「あそこです。」 “Asoko desu.” “It’s over there.” |

7. |

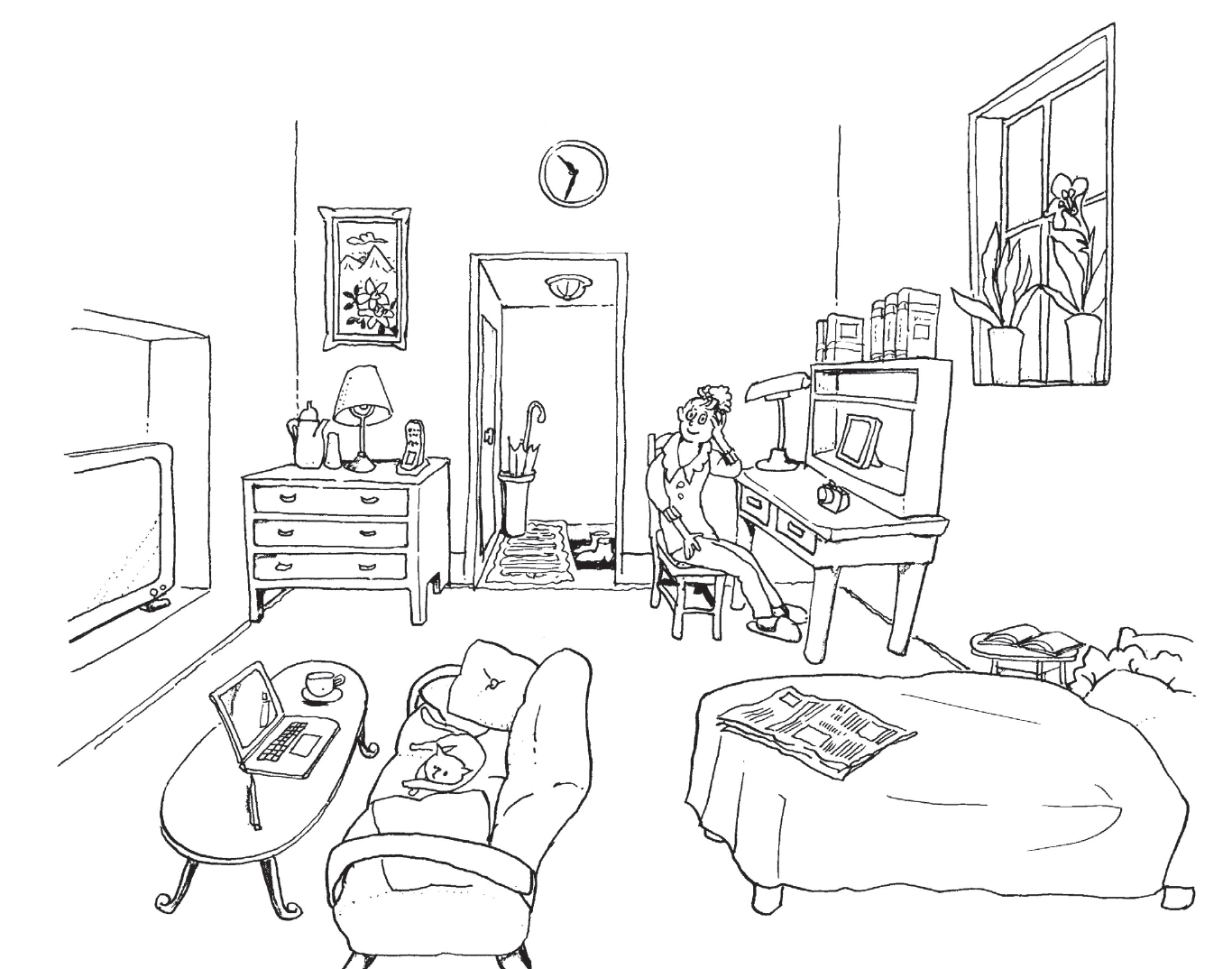

「パソコンはどこにありますか。」 “Pasokon wa doko ni arimasu ka.” “Where is the computer?” |

「机の上にあります。」 “Tsukue no ue ni arimasu.” “It’s on the top of the desk.” |

8. |

「マイクさんはどこにいますか。」 “Maiku-san wa doko ni imasu ka.” “Where is Mike?” |

「銀行にいます。」 “Ginkō ni imasu.” “He is at the bank.” |

9. |

「アンさん。アンさんは日本の 食べ物が好きですか。」 “An-san. An-san wa Nihon no tabemono ga suki desu ka.” “Ann, do you like Japanese food?” |

「ええ, 大好きです。」 “Ē, daisuki desu.” “Yep, I love it.” |

10. |

「日本のアニメはどうですか。」 “Nihon no anime wa dō desu ka.” “What do you think of Japanese anime?” |

「素晴らしいです。」 “Subarashii desu.” “(It) is wonderful.” |

|

[cue 02-2] |

Basic Vocabulary

IN MY ROOM

部屋 heya |

room |

テーブル tēburu |

table |

ソファー sofā |

sofa |

ベッド beddo |

bed |

椅子 isu |

chair |

机 tsukue |

desk |

パソコン pasokon |

computer (lit., personal computer) |

テレビ terebi |

TV |

リモコン rimokon |

remote control |

スタンドライト sutandoraito |

floor/table/desk lamp |

充電器 jūdenki |

battery charger, charger |

鉛筆 enpitsu |

pencil |

ペン pen |

pen |

時計 tokei |

clock, watch |

カメラ kamera |

camera |

本 hon |

book |

新聞 shinbun |

newspaper |

雑誌 zasshi |

magazine |

PLACES

駅 eki |

train station |

郵便局 yūbinkyoku |

post office |

銀行 ginkō |

bank |

病院 byōin |

hospital |

映画館 eigakan |

movie theater |

レストラン resutoran |

restaurant |

喫茶店 kissaten |

coffee shop |

ネットカフェ netto kafe |

cyber café |

ATM ei tī emu |

ATM |

スーパー sūpā |

supermarket |

PEOPLE

人 hito |

person, people |

友達 tomodachi |

friend |

学生 gakusei |

student |

先生 sensei |

teacher |

SCHOOLS

学校 gakkō |

school |

高校 kōkō |

high school |

大学 daigaku |

college, university |

大学院 daigakuin |

graduate school |

CULTURE NOTE Netto Kafe

Internet cafés in Japan are called netto kafe or nekafe, and are found in most major cities. They are actually very complex. In addition to desktop computers, Internet access, and drinks, they offer tons of comic books, magazines, and DVDs for the customers to read and watch as much as they want during their stay. They are usually open 24/7, and the customers are charged by time. They offer some private rooms in different sizes so the customers can read or watch undisturbed by others. Some netto kafes have comfortable reclining chairs, massage chairs, and shower rooms as well as billiards, karaoke, and darts. It is possible for homeless people to live in netto kafes in Japan, because a one-night stay could cost as little as ten dollars, and such people are called netto nanmin ‘net refugees.’

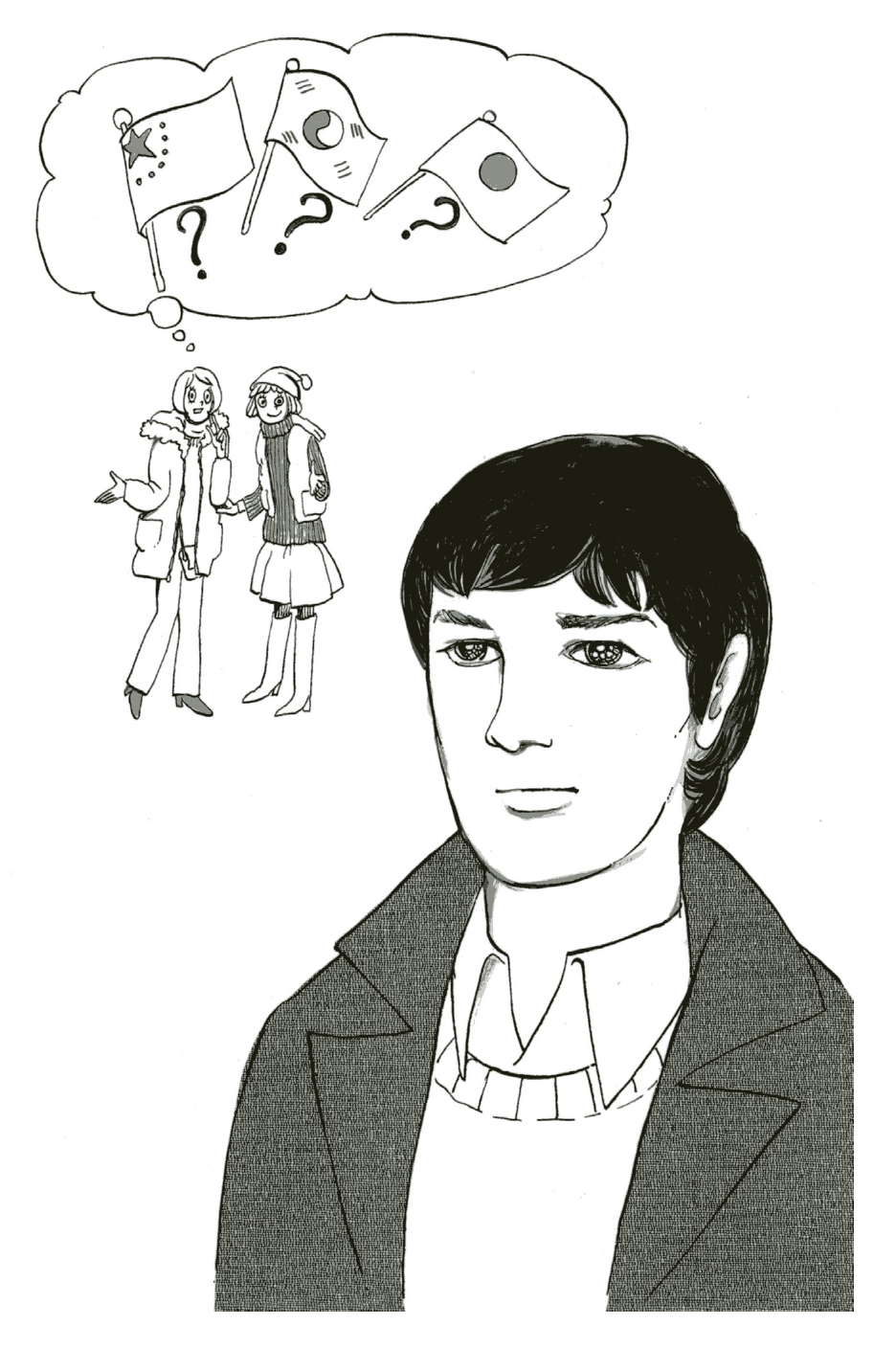

COUNTRIES

日本 Nihon/Nippon |

Japan |

アメリカ Amerika |

The United States of America |

イギリス Igirisu |

England |

中国 Chūgoku |

China |

韓国 Kankoku |

South Korea |

オーストラリア Ōsutoraria |

Australia |

フランス Furansu |

France |

ドイツ Doitsu |

Germany |

スペイン Supein |

Spain |

インド Indo |

India |

フィリピン Filipin |

The Philippines |

ロシア Roshia |

Russia |

PEOPLE

日本人 Nihon-jin |

Japanese |

アメリカ人 Amerika-jin |

American |

中国人 Chūgoku-jin |

Chinese |

韓国人 Kankoku-jin |

Korean |

フランス人 Furansu-jin |

French |

LANGUAGES

日本語 Nihongo |

Japanese |

英語 Eigo |

English |

中国語 Chūgokugo |

Chinese |

韓国語 Kankokugo |

Korean |

フランス語 Furansugo |

French |

Structure Notes

2.1. Nouns and pronouns

Nouns are words that name people, places, things, and concepts such as hito ‘person,’ Yamada ‘(Ms.) Yamada,’ zasshi ‘magazine,’ and uchi ‘house.’ Nouns often precede a particle like wa, ga, no, and ni, or occur before the word desu ‘is (equals).’

Pronouns refer to people and things. Personal pronouns refer to people. Watashi means ‘I’ or ‘me.’ In a formal situation watakushi is used instead of watashi. Women also say atashi in an informal situation. Men often say boku for ‘I, me’; a rougher term is ore. The pronoun ‘you’ in Japanese is anata, and a rougher term is anta. Kimi is a slightly intimate term for ‘you’; a condescending form is omae (sometimes used to small children). However, you should remember to avoid using these second-person pronouns (you) as much as possible: you can drop the pronoun or use the name or the title of the person. Kare means ‘he’ or ‘him’ and kanojo means ‘she’ or ‘her,’ but again, you can use the name or the title of the person as much as possible.

Demonstrative pronouns can be conveniently used for referring to items that both the speaker and the listener can see. For referring to things, use kore, sore, or are. For referring to locations use koko, soko, or asoko. (See 2.15. for related words.)

これ kore

this one

それ sore

that one near you

あれ are

that one over there

どれ dore

which one

ここ koko

this place, here

そこ soko

that place (near you), there

あそこ asoko

over there

どこ doko

where

「先生, これは先生の傘ですか。」

“Sensei, kore wa sensei no kasa desu ka.”

“Professor, is this your umbrella?”

「いいえ, それはマイクさんの傘です。」

“Īe, sore wa Maiku-san no kasa desu.”

“No, it’s Mike’s.”

2.2. Prenouns

The words kono, sono, and ano are prenouns, or more commonly called demonstrative adjectives. These words precede a noun and modify its meaning, much as a noun is modified by a phrase consisting of a noun followed by the particle no: kono gakkō ‘this school,’ watashi no gakkō ‘my school.’

この kono

this

その sono

that

あの ano

that over there

どの dono

which

2.3. Place words (relative location)

Words such as ue ‘topside’ and naka ‘inside’ are used along with reference nouns as in tēburu no ue ‘on the top of the table.’ They are often used for situations we would express in English with prepositions like in, on, under, behind, above, and between.

前 mae

in front

後ろ ushiro

behind

右 migi

right

左 hidari

left

上 ue

up

下 shita

below

そば soba

beside, near

近く chikaku

near(by)

中 naka

inside

外 soto

outside

隣 tonari

next door, next position

間 aida

between (two places)

Here are some example sentences.

駅は銀行の後ろです。

Eki wa ginkō no ushiro desu.

The train station is behind the bank.

充電器はテーブルの下にあります。

Jūdenki wa tēburu no shita ni arimasu.

The charger is under the table.

2.4. Adjectival nouns

The word suki ‘likable’ is a special kind of noun called an adjectival noun (or copular noun, nominal adjective). It acts as an adjective describing a noun, but it patterns like a noun, being placed before some form of the copula da/desu ‘is (equals).’ Here are a few examples:

好き(だ) suki (da)

(is) likable, liked

嫌い(だ) kirai (da)

(is) dislikable, disliked

きれい(だ) kirei (da)

(is) neat, pretty, clean

シック(だ) shikku(da)

(is) chic, stylish

派手(だ) hade (da)

(is) showy

静か(だ) shizuka (da)

(is) quiet

まじめ(だ) majime (da)

(is) serious, studious

簡単(だ) kantan (da)

(is) easy

駄目(だ) dame (da)

(is) not good

Notice that the literal translation of suki desu and kirai desu is ‘(something) is liked’ and ‘(something) is disliked,’ but we freely translate them ‘(somebody) likes (something)’ and ‘(somebody) dislikes (something).’

2.5. Untranslated English words

In English we seldom say just ‘book.’ We say ‘a book,’ ‘the book,’ ‘some books,’ or ‘the books.’ In Japanese, the situation is just the other way around. Since the Japanese have another way of implying that they’ve been talking about the noun, by making it the topic with the particle wa, as in hon wa ‘the book, the books,’ they don’t need a word to translate ‘the.’ And they usually leave it up to the situation to make it clear whether there are several things in question or just one, unless they want to focus your attention on the number itself, in which case the number word indicates just how many you are talking about. The Japanese, like everyone else, do not always bother to express things they think you already know. This doesn’t mean they lack ways to say things we do; it just means they leave implied some of the things we are used to saying explicitly. Americans tend to use watashi and anata too much. Remember to omit pronouns when the reference is clear.

2.6. Particles

In English, we usually show the relations between words in the way we string them together. The sentences ‘Jon loves May’ and ‘May loves Jon’ both contain the same three words, but the order in which we put the words determines the meaning. In Japanese, relations between words are often shown by little words called particles. This lesson will introduce you to several of these particles: wa, ga, ka, no, and ni.

2.7. は wa

The particle wa sets off the TOPIC you are going to talk about. If you say Watashi wa gakusei desu ‘I am a student,’ the particle shows you are talking about watashi ‘I’—what you have to say about the topic then follows. A pidgin-English way of translating this particle wa is ‘as for’: Shinbun wa koko ni arimasu ‘As for the newspaper, it’s here.’ But it is better not to look for a direct translation for some of these particles—remember they just indicate the relationship between the preceding words and those that follow.

2.8. が ga

The particle ga shows the subject. In Eiga ga suki desu ‘I like movies,’ the particle ga shows that eiga ‘movies’ is the subject of suki desu ‘are liked.’ The difference between the particles wa and ga is one of emphasis. In English we make a difference in emphasis by using a louder voice somewhere in the sentence. We say ‘I like MOVIES’ or ‘I LIKE movies,’ depending on which part of the sentence we want to bring out. In Japanese, the particle ga focuses our attention on the words preceding it, but the particle wa releases our attention to focus on some other part of the sentence. So, eiga ga suki desu means ‘I like MOVIES,’ but eiga wa suki desu means ‘I LIKE movies.’ When there is a question word in the sentence (like dare ‘who,’ dore ‘which one,’ dono ‘which,’ and doko ‘where’), the attention usually focuses on this part of the sentence, so the particle wa is not used: Dono tatemono ga eki desu ka ‘Which building is the train station?’ Since our attention is focused on ‘WHICH building,’ the answer is Ano tatemono ga eki desu ‘THAT building is the train station.’ If the question is Ano tatemono wa nan desu ka ‘What is that building?,’ our attention is released from ano tatemono ‘that building’ by the particle wa and concentrates on ‘WHAT,’ so the answer is Ano tatemono wa eki desu ‘That building is a TRAIN STATION,’ or just Eki desu ‘It’s a train station.’ Some sentences have both a topic—or several successive topics—and a subject:

あなたは日本のアニメが好きですか。

Anata wa Nihon no anime ga suki desu ka.

Do you like Japanese anime?

あなたは日本のアニメは好きですか。

Anata wa Nihon no anime wa suki desu ka.

Do you LIKE Japanese anime?

Because the difference in meaning between wa and ga is largely one of emphasis, you can often take a sentence and change the emphasis just by substituting wa for ga. The particle wa can be thought of us an “attention-shifter”: the words preceding it set the stage for the sentence, and serve as scenery and background for what we are going to say. This can lead to ambiguity. The sentence Tarō wa Hanako ga suki desu (literally, ‘Taro as topic, Hanako as emphatic subject, someone is liked’) can mean either ‘Taro likes Hanako’ (It’s HANAKO that Taro likes’) or ‘Hanako likes Taro’ (It’s HANAKO that likes Taro). The situation usually makes it clear which meaning is called for. If you have both wa and ga in a sentence, the phrase with wa usually comes first: the stage is set before the comment is made.

Sometimes two topics are put in contrast with each other: Kore wa eigakan desu ga, sore wa ginkō desu ‘This is a movie-theater, but that is a bank.’ (The particle ga meaning ‘but’ is not the same particle as the one indicating the subject.) In this case, the emphasis is on the way in which the two topics contrast—in being a theater on the one hand, and a bank on the other.

2.9. か ka

The particle ka is placed at the end of a sentence to show that it is a question. It is as if we were pronouncing the question mark:

あの家です。

Ano ie desu.

It’s that house.

あの家ですか。

Ano ie desu ka.

Is it that house?

A common way of asking a question in Japanese is to give two or more alternatives, one of which the answerer selects.

あの人は日本人ですか。中国人ですか。

Ano hito wa Nihon-jin desu ka. Chūgoku-jin desu ka.

Is he Japanese or Chinese? (Literally, ‘Is he Japanese. Is he Chinese?’)

Alternative questions are further discussed in Note 7.8.

2.10. の no

The particle no shows that the preceding noun “modifies” or “limits” the noun following. The particle no is often equivalent to the English translation of, but sometimes it is equivalent to in or other words.

私の本 watashi no hon

my book

日本語の本 Nihongo no hon

Japanese (language) books

私の友達 watashi no tomodachi

my friend

部屋の中 heya no naka

the inside of the room

家の外 ie no soto

the place outside the house

ここの学校 koko no gakkō

the schools of this place, the schools here

東京の銀行 Tōkyō no ginkō

banks in Tokyo

アメリカの新聞 Amerika no shinbun

American newspapers

日本の会社員 Nihon no kaishain

company employees in Japan

The expression NOUN + no is sometimes followed directly by the copula desu ‘is (equals),’ as in:

「これはだれのですか。」

“Kore wa dare no desu ka.”

“Whose is this?”

「石田さんのです。」

“Ishida-san no desu.”

“It’s Ms. Ishida’s.”

2.11. に ni

The particle ni indicates a “general sort of location” in space or time, which can be made more specific by putting a place or time word in front of it. The phrase heya ni means ‘at the room, in the room.’ To say explicitly ‘in(side) the room,’ you insert the specific place word naka ‘inside’: heya no naka ni. Notice the difference between gakkō ni imasu ‘he’s at school, he’s in school’ and gakkō no naka ni imasu ‘he’s in(side) the school (building).’

A NOUN PHRASE + ni is not used to modify another noun, and it does not occur before desu ‘is (equals)’; it is usually followed by arimasu ‘(a thing) is (exists)’ or imasu ‘(a person) is (exists in a place).’ To say ‘the people in the room,’ you connect heya no naka ‘the inside of the room’ with hito ‘the people’ by means of the particle no: heya no naka no hito.

The particle ni is also used figuratively:

友達に言いました。

Tomodachi ni iimashita.

He said TO his friend.

It sometimes shows “purpose”:

散歩に行きました。

Sanpo ni ikimashita.

He went FOR a walk.

It is also used to indicate a “change of state” and after an adjectival noun, to show “manner”:

先生になりました。

Sensei ni narimashita.

He became a teacher, he turned into a teacher.

ネットカフェにしました。

Netto kafe ni shimashita.

They made it into an Internet café.

きれいに書きました。

Kirei ni kakimashita.

He wrote neatly.

Occasionally, a particle like ni will be used in an expression that calls for an unexpected equivalent in the English translation:

だれに日本語を習いましたか。

Dare ni Nihongo o naraimashita ka.

Who did you learn Japanese FROM?

2.12. Words meaning ‘is’

In this lesson we find three different Japanese words translated as ‘is’ in English: desu, arimasu, and imasu. The word desu is the COPULA and it means ‘equals.’ Whenever an English sentence containing the word is makes sense if you substitute equals for is, the Japanese equivalent is desu.

あれは富士山です。

Are wa Fujisan desu.

That is Mt. Fuji. (That one = Mt. Fuji)

あの人は私の友達です。

Ano hito wa watashi no tomodachi desu.

That person is my friend. (That person = my friend)

それは私のです。

Sore wa watashi no desu.

That’s mine. (That = mine)

Preceding the word desu, there is always a noun or a phrase consisting of NOUN + no or some other particle, but never wa, ga, o (discussed in 3.6.), de (discussed in 3.5), or ni.

When an English sentence containing the word is makes sense if you reword it as ‘(something) exists,’ the Japanese equivalent is arimasu:

ATMがあります。

ATM ga arimasu.

There is an ATM.

When the English sentence can be reworded ‘(something) exists in a place’ or ‘(something) is located,’ the usual Japanese equivalent is also arimasu:

リモコンはそこにあります。

Rimokon wa soko ni arimasu.

The remote control is there.

But often, especially if the topic is itself a place, for example, a city, a building, a street, a location, either desu or (ni) arimasu may be used:

映画館はあそこです。/映画館はあそこにあります。

Eigakan wa asoko desu./Eigakan wa asoko ni arimasu.

The movie theater is over there.

お台場はどこですか。/お台場はどこにありますか。

Odaiba wa doko desu ka./Odaiba wa doko ni arimasu ka.

Where is Odaiba?

When an English sentence containing the word is makes sense reworded as ‘(somebody) exists (in a place)’ or ‘(somebody) stays (in a place)’ or ‘(somebody) is located,’ the Japanese equivalent is imasu ‘stays’:

「あの人はどこにいますか。」

“Ano hito wa doko ni imasu ka.”

“Where is he?”

「外にいます。」

“Soto ni imasu.”

“He’s outside.”

There are other uses of these two verbs, arimasu and imasu, which we will examine later. It may help to think of tag meanings for these words as follows: desu ‘equals,’ arimasu ‘exists,’ imasu ‘stays.’ Note that ‘exists’ is the usual way of saying ‘(somebody) has (something)’:

プリンターはありますか。

Purintā wa arimasu ka.

Do you have a printer? (Does a printer exist?)

2.13. Inflected words

Words like desu, arimasu, and imasu are called inflected words, because their shapes can be changed (inflected) to make other words of similar but slightly different meaning. In English, we change the shapes of inflected words to show a difference of subject—‘I am, you are, he is; I exist, he exists,’ as well as a difference of time—‘I am, I was; you are, you were.’ In Japanese, the shape of an inflected word stays the same regardless of the subject: Gakusei desu can mean ‘I am a student, you are a student, he is a student, we are students, you are students, they are students’ depending on the situation. If you want to make it perfectly clear, you can put in a topic: Watashi wa gakusei desu, anata wa gakusei desu, ano hito wa gakusei desu.

2.14. Dropping subject nouns

In English, every normal sentence has a subject and a predicate. If there is no logical subject, we stick one in anyway: ‘IT rains’ (what rains?), ‘IT is John’ (what is John—it?). Sentences that do not contain a subject are limited to commands—‘Keep off the grass!’—in which a sort of ‘you’ is understood, or to a special style reserved for postcards and telegrams, for example, ‘Arrived safely. Wish you were here.’ In Japanese, the normal sentence type contains a predicate, Arimasu ‘There is (some),’ Kamera desu ‘(It) is a camera’—and to this we may add a subject or a topic, but it isn’t necessary unless we wish to be explicit. Since the topic of a sentence is usually obvious in real conversation, the Japanese often doesn’t mention it at all, or occasionally throws it in as an afterthought.

A predicate may consist of a simple verb, arimasu, imasu, or of a noun plus the copula, Kyōshi desu ‘It’s (I’m) a teacher,’ but it cannot consist of the copula alone. The Japanese can talk about the equation A = B, that is A wa B desu as in Kore wa kamera desu ‘This is a camera,’ by dropping the topic (A) and just saying = B, that is B desu as in Kamera desu ‘(It) is a camera.’ But they never say just = (desu) or give a one-sided equation like A = (B). Something has to fill the blank before the word desu, in all cases.

2.15. Words of relative reference and question words

Notice the related shapes and meaning of the following classes of words:

わたし

watashi

I

あなた

anata

you

あの人

ano hito

he, she

だれ

dare

who

これ

kore

this one

それ

sore

that one near you

あれ

are

that one over there

どれ

dore

which one

この

kono

(of) this

その

sono

(of) that

あの

ano

(of) that there

どの

dono

which

こんな

konna

like this

そんな

sonna

like that one near you

あんな

anna

like that one over there

どんな

donna

what sort of

ここ

koko

here

そこ

soko

there

あそこ

asoko

over there

どこ

doko

where

こう

kō

in this way

そう

sō

in that way

ああ

ā

in that way there

どう

dō

in what way, how

The words in the column with watashi are used to refer to something near the speaker. The words in the column with anata refer to something near the person you are talking with, or to something you have just mentioned. The words in the column with ano hito refer to something at a distance from both you and the person you are talking with. For some situations, either those in the column with anata or those in the column with ano hito may be heard, since the reference is a relative matter. Be sure to keep dare ‘who’ and dore ‘which’ distinct. Instead of konna, sonna, anna, and donna, we often hear the more colloquial kō iu, sō iu, ā iu, and dō iu. (Note that iu ‘says’ is often pronounced as if spelled yū or ‘you.’)

その中にカメラがあります。

Sono naka ni kamera ga arimasu.

Inside it, there is a camera.

どんな本ですか。

Donna hon desu ka.

What sort of book is it?

どうですか。

Dō desu ka.

How is it?

あの人はだれですか。

Ano hito wa dare desu ka.

Who is that person?

2.16. Words for ‘restaurant’

There are a number of different words for various types of restaurant in Japan. You will often hear the word resutoran, from the English word of French origin. Other words include old-fashioned shokudō ‘dining room/hall,’ kissa or kissaten ‘a kind of French-type café,’ and specialized restaurants or shops that end in ya ‘store,’ as in sushiya ‘a sushi restaurant,’ sobaya ‘a noodle restaurant,’ yakinikuya ‘a table-top BBQ restaurant,’ yakitoriya ‘a grilled chicken restaurant,’ and izakaya, a friendly bar that serves home-style dishes and alcoholic beverages.

Ryōtei is a rather high-class traditional Japanese restaurant. In addition, there are many American-style fast-food restaurants that serve hamburgers, donuts, and fried chicken.

2.17. Words for ‘toilet’

As in English, there are various oblique ways of talking about toilets in Japanese. Probably the most current polite terms are otearai ‘lavatory’ and (o)toire ‘toilet,’ but women may say keshōshitsu ‘powder room.’ So when asking where it is, you may say O-tearai wa doko ni arimasu ka.

2.18. 何 nani/nan ‘what’

The word meaning ‘what’ is usually expressed by nan before a word beginning with t, d, or n, and nani before other words. However, nan- ‘how many’ never has the shape nani-.

何ですか。

Nan desu ka.

What is it?

何と言いましたか。

Nan to iimashita ka.

What did (he) say?

何の本ですか。

Nan no hon desu ka.

What book is it?

何がありますか。

Nani ga arimasu ka.

What is there? What do you have?

何をしていますか。

Nani o shite imasu ka.

What are you doing?

CDが何枚ありますか。

Shī dī ga nan-mai arimasu ka.

How many CDs do you have?

本が何冊ありますか。

Hon ga nan-satsu arimasu ka.

How many books are there?

|

[cue 02-3] |

Conversation

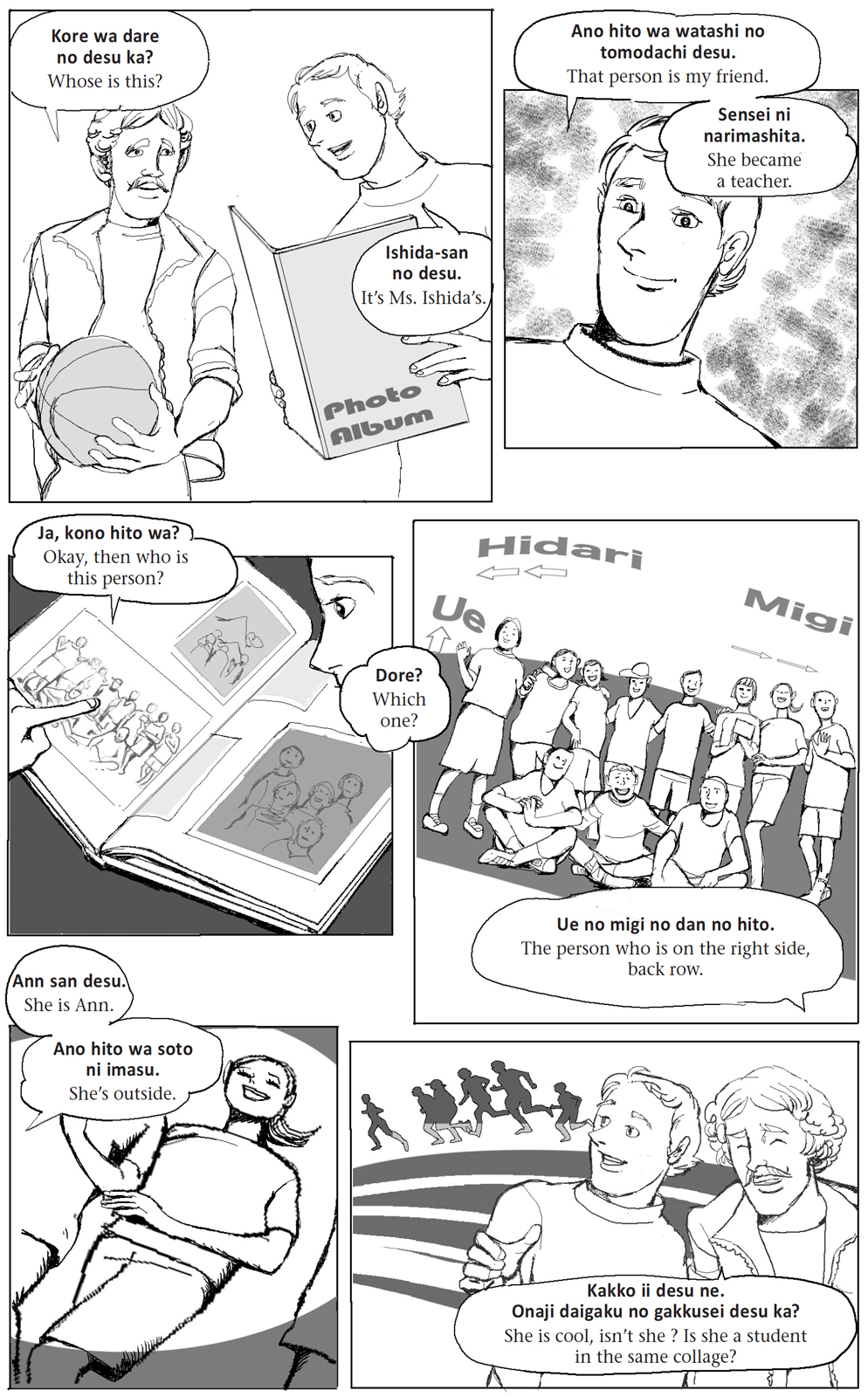

Emi (E) is a member of a rock band formed in her college. She shows a photo of the members to Masahiro (M).

M: これは恵美さんですか。

Kore wa Emi-san desu ka.

Is this you, Emi?

E: ええ。

Ē.

Yes.

M: ぜんぜん違いますね。

Zenzen chigaimasu ne.

Look so different.

E: そうですか。

Sō desu ka.

Really?

M: この人はだれですか。

Kono hito wa dare desu ka.

Who is this person?

E: 洋介です。ギタリストです。

Yōsuke desu. Gitarisuto desu.

Yosuke. He is a guitarist.

M: かっこいいですね。同じ大学の学生ですか。

Kakko ii desu ne. Onaji daigaku no gakusei desu ka.

He is cool, isn’t he? Is he a student in the same college?

E: ええ。

Ē.

Yes.

M: じゃあ、この人は?

Jā, kono hito wa?

Okay, then. Who is this person?

E: ベーシストの拓也です。

Bēshisuto no Takuya desu.

He is Takuya, the bassist.

M: ドラマーはだれ?

Doramā wa dare?

Who is the drummer?

E: 私。

Watashi.

Me.

Exercises

* Do it aloud; don’t write the answers down.

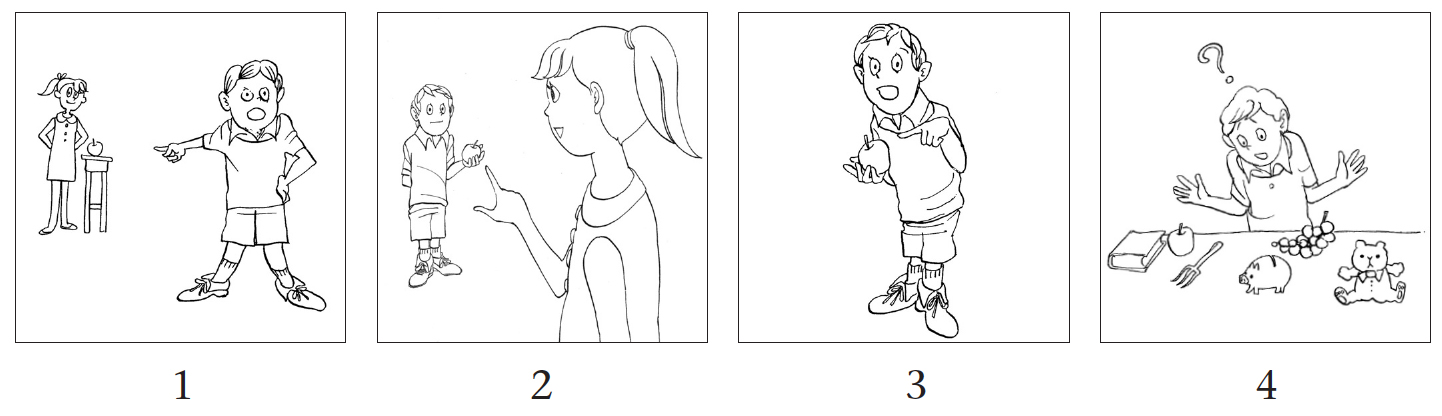

I. For each situation illustrated below, choose which word the speaker would use, kore, sore, are, or dore.

II. Fill in the blanks with the appropriate particles.

1. あの建物——何ですか。 Ano tatemono —— nan desu ka. What is that building?

2. 私——学生です。 Watashi —— gakusei desu. I’m a student.

3. 私——本です。 Watashi —— hon desu. It’s my book.

4. 新聞はテーブル——下にあります。 Shinbun wa tēburu —— shita ni arimasu. The newspaper is under the table.

5. どれ——あなたのですか。 Dore —— anata no desu ka. Which one is yours?

III. Choose the appropriate item in the parentheses.

1. (あれ・あの)は富士山です。 (Are, ano) wa Fujisan desu. That’s Mt. Fuji.

2. (これ・この)カメラはだれのですか。 (Kore, kono) kamera wa dare no desu ka. Whose camera is this?

3. 「それは何ですか。」「(それ・これ)はカメラです。」 “Sore wa nan desu ka.” “(Sore, kore) wa kamera desu.” “What is that?” “It’s a camera.”

4. 郵便局は(あれ・あそこ)にあります。 Yūbinkyoku wa (are, asoko) ni arimasu. The post office is over there.

5. 銀行は(あれ・あの)です。 Ginkō wa (are, ano) desu. The bank is that one over there.

IV. Fill in the blanks with one of the words です desu, あります arimasu, or います imasu.

1. あなたは学生———か。 Anata wa gakusei ——— ka. Are you a student?

2. 銀行はどこ———か。 Ginkō wa doko ——— ka. Where is the bank?

3. ホテルはどこに———か。 Hoteru wa doko ni ——— ka. Where is the hotel?

4. 犬はどこに———か。 Inu wa doko ni ——— ka. Where is the dog?

5. 机の下には雑誌が———。 Tsukue no shita ni wa zasshi ga ———. There is a magazine under the desk.