LESSON 9

Be Polite!

礼儀正しく!

Reigi Tadashiku!

In this lesson you will learn a variety of prefixes, suffixes, forms, and words that make your speech very polite.

|

[cue 09-1] |

Basic Sentences

1. |

ご無沙汰いたしております。 Gobusata itashite orimasu. Haven’t seen you for a long time! (lit., I have not visited you frequently enough.) |

|

2. |

お元気でいらっしゃいますか。 O-genki de irasshaimasu ka. How are you? |

|

3. |

はい,お陰さまで。 Hai, okagesama de. I’m fine, thanks to everyone. |

|

4. |

お父様はいかがですか。 Otōsama wa ikaga desu ka. How is your father? |

|

5. |

父も元気にしております。 Chichi mo genki ni shite orimasu. My father is also fine. |

|

6. |

先月田中先生にお会いいたしました。 Sengetsu Tanaka sensei ni o-ai itashimashita. Last month I met Professor Tanaka. |

|

7. |

どちらでお会いになったんですか。 Dochira de o-ai ni natta n desu ka. Where did you meet him? |

|

8. |

博物館でございました。 Hakubutsukan de gozaimashita. It was at the museum. |

|

9. |

田中先生にいろいろ教えて頂きました。 Tanaka sensei ni iroiro oshiete itadakimashita. Professor Tanaka taught me a variety of things. (lit., I received the favor of teaching a variety of things from Prof. Tanaka.) |

|

10. |

高橋先生はお忙しくていらっしゃいますか。 Takahashi sensei wa o-isogashikute irasshaimasu ka. Is Professor Takahashi busy? |

|

11. |

「4月の学会にはおいでにならないのですか。」 “Shigatsu no gakkai ni wa oide ni naranai no desu ka.” “You are not going to the conference in April?” |

「はい,参りません。」 “Hai, mairimasen.” “Correct, I’m not going.” |

12. |

近いうちにまたお伺いいたします。 Chikai uchi ni mata o-ukagai itashimasu. I’ll visit you soon. |

|

13. |

他の先生方にも宜しくお伝えください。 Hoka no sensei-gata ni mo yoroshiku o-tsutae kudasai. Please send my best regards to the other teachers. |

|

|

[cue 09-2] |

Basic Vocabulary

POLITE PHRASES

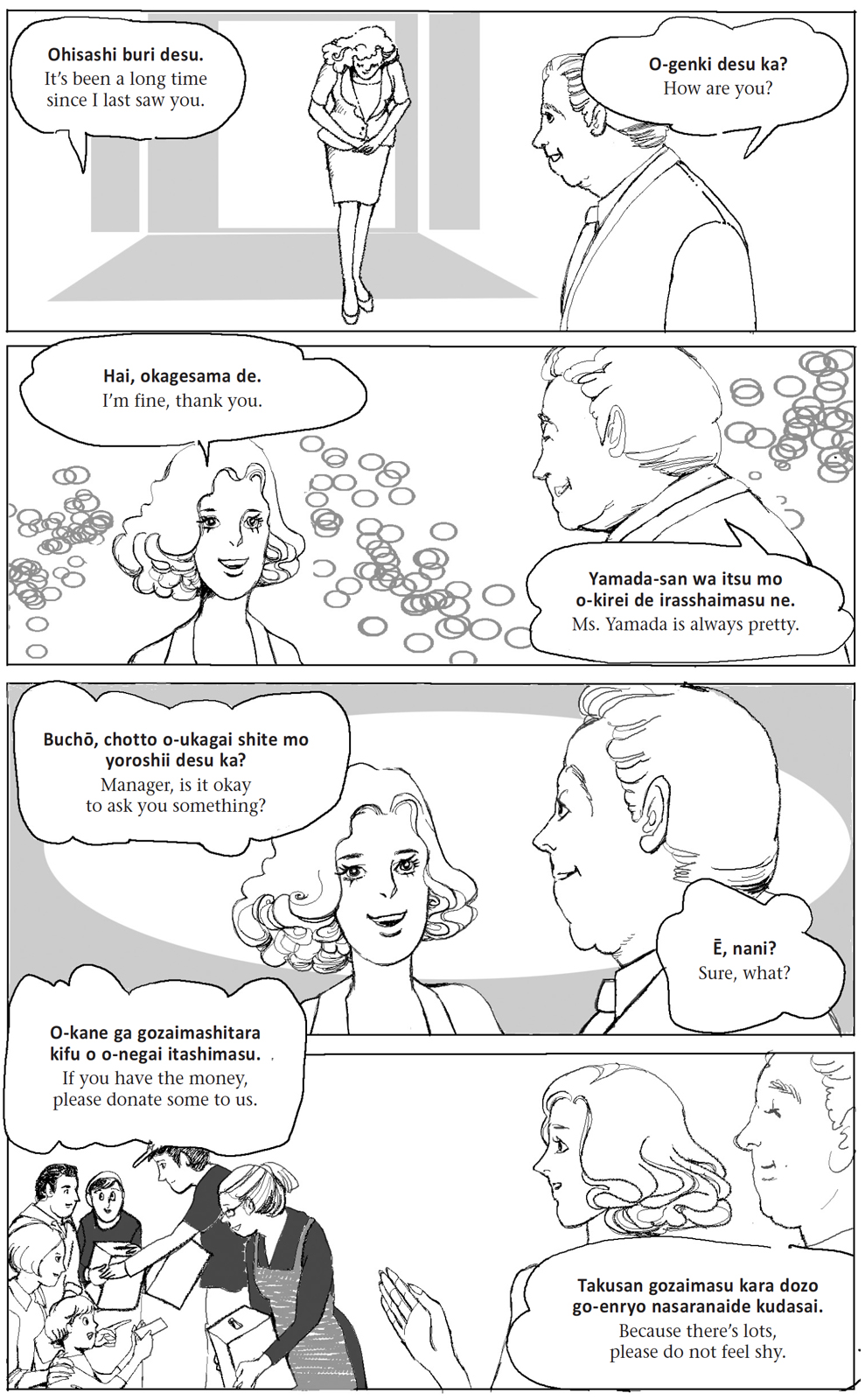

お久しぶりです。 O-hisashiburi desu. |

It’s been a long time since I saw you last. |

お元気ですか。 O-genki desu ka. |

How are you? |

お陰さまで。 Okagesama de. |

(I’m fine) thanks to (you and others). |

失礼します。 Shitsurei shimasu. |

(Expression used when one parts. Lit., I’ll be rude.) |

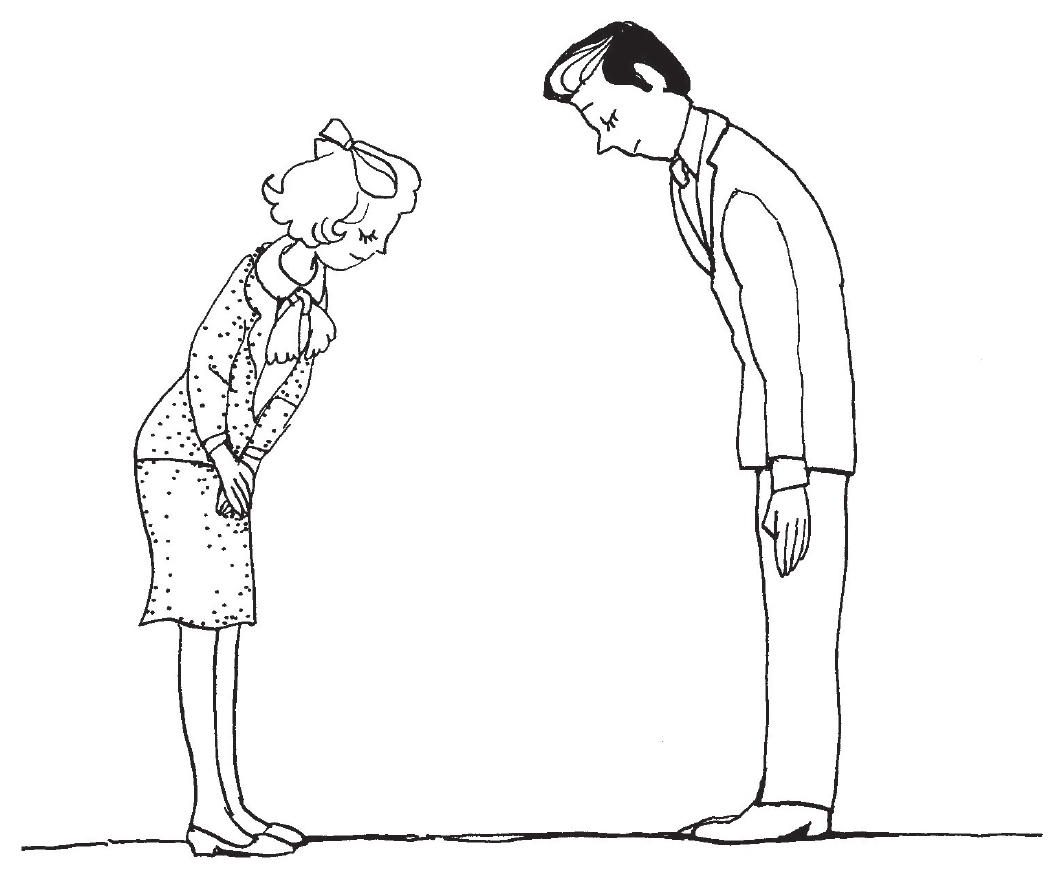

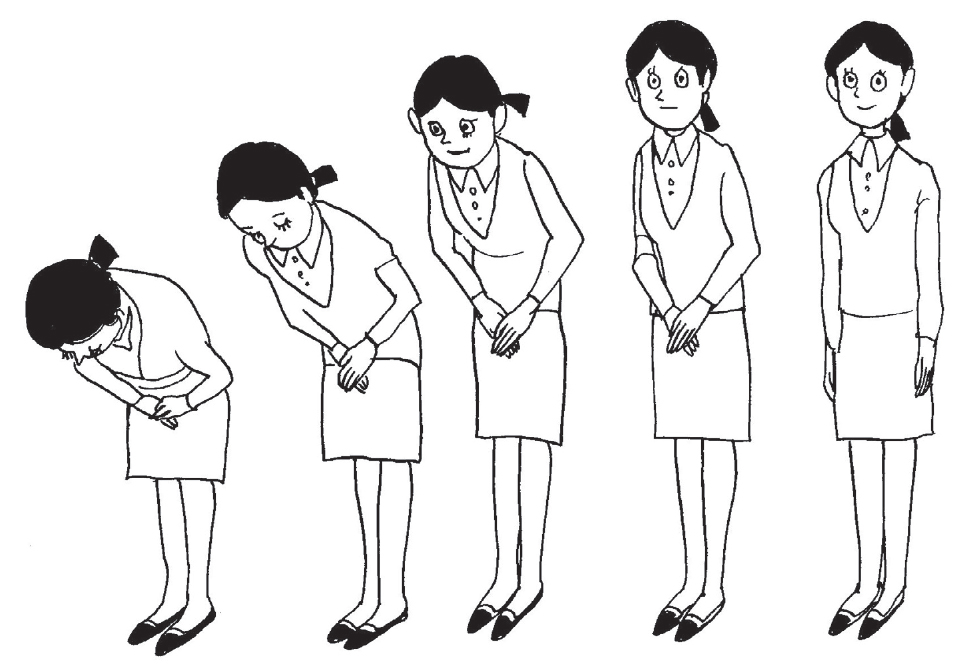

CULTURE NOTE Bowing

Bowing plays an important role for communication in Japan. Phrases for gratitude, apology, greeting, and parting are almost always accompanied by bowing. People sometimes bow without saying anything. The deeper the bow, the deeper the respect for the person to whom you are bowing. The bow is called the お辞儀 ojigi, or more formally 礼 rei. The former is more common because the latter is only one syllable. The deepest bow is called 最敬礼 saikeirei. The deep bow, lowering the upper half of the body by 45 degrees, is required if you make a horrible mistake, receive overwhelming kindness, or associate with people to whom you must show serious respect. Otherwise, you don’t have to bow very deeply. You can lower your upper body only by about 10–15 degrees, or just tilt your head forward for a moment or two in casual situations. When introductions are being made, Japanese do not shake hands, hug, or kiss, but just bow and smile.

POLITE QUESTIONS

いかがですか。 Ikaga desu ka. |

How is it? |

どなたですか。 Donata desu ka. |

Who is it? |

どちらですか。 Dochira desu ka. |

Where is it?/Which one is it? |

おいくつですか。 O-ikutsu desu ka. |

How old are you? |

おいくらですか。 O-ikura desu ka. |

How much is it? |

どちらからですか。 Dochira kara desu ka. |

Where are you from? |

POLITE PHRASES AT RESTAURANTS

いらっしゃいませ。 Irasshaimase. |

Welcome! |

ご注文は。 Go-chūmon wa. |

What is your order? |

少々お待ちください。 Shōshō o-machi kudasai. |

Please wait a little bit. |

お待たせいたしました。 O-matase itashimashita. |

Sorry to have kept you waiting. |

申し訳ございません。 Mōshiwake gozaimasen. |

I’m terribly sorry. |

ありがとうございました。 Arigatō gozaimashita. |

Thank you so much! |

VERBS OF GIVING AND RECEIVING

あげる・あげます ageru/agemasu |

gives |

差し上げる・差し上げます sashiageru/sashiagemasu |

gives (honorific) |

くれる・くれます kureru/kuremasu |

gives (to me/us) |

下さる・下さいます kudasaru/kudasaimasu |

gives (to me/us, honorific) |

もらう・もらいます morau/moraimasu |

receives |

頂く・頂きます itadaku/itadakimasu |

receives (honorific) |

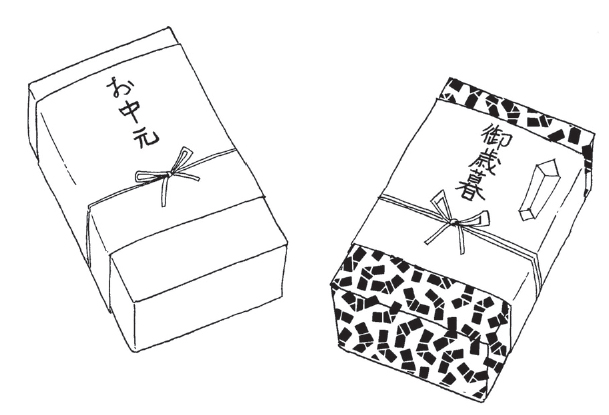

CULTURE NOTE Gift-giving

The Japanese send gifts to their bosses, clients, former teachers, friends, and relatives. There are two major gift-giving seasons in Japan: one is in summer, and the other is at the end of the year. The summer gift is called ochūgen, and the end-of-year gift is called oseibo. Popular ochūgen and oseibo gifts are foods and beverages such as pasta, cheese, seaweed, dried shitake mushrooms, cooking oil, canned foods, beer, sake, cookies, cakes, and items for daily living such as soap and towels. People usually purchase the gifts at a well-known department store and have the store wrap them with the store’s wrapping paper and send them directly to their relatives, superiors, and friends. During these seasons, the ochūgen and oseibo counter at department stores is very crowded with people clutching address books.

Structure Notes

9.1. Status words: humble, neutral, exalted

A word or expression in Japanese may have one of three connotations, indicating its reference to a social status: humble, neutral, and exalted. Many textbooks refer to the exalted forms as “honorific.” In this book, honorific is used to refer to BOTH the humble and exalted forms, and to the style of speech in which they usually occur. Most of the words and expressions you have learned so far are neutral. These are used in reference to anyone, provided you are not showing a special deference. Ordinarily, however, Japanese use a more polite level of speech—the honorific style—in speaking to older people, officials, strangers, guests, and so forth. And even in the ordinary polite level you use to a friend of your own age, it is customary to show deference to the other person and his family by using exalted forms for kinship terms and certain other words. Humble forms are only used when speaking of yourself or members of your family to other people. When directly addressing a member of your family you use the exalted term if the person is older, for example, Okāsan ‘Mother’ and Onīsan ‘Older Brother.’ The given name is used if the person is younger: Jirō ‘(younger brother) Jiro.’

For many expressions, including most nouns, there is no special humble form. Instead, the neutral form is used for the humble situations in contrast with the exalted form. In speaking very politely to someone of equivalent social rank, you usually use the exalted forms for reference to him or her and his or her actions, and the simple neutral forms in reference to yourself and your own actions, unless your actions can be construed as involving the other person or his or her family or property, or as involving someone else of higher social status than yourself, in which case you use the humble forms. If you are speaking to someone of much superior social rank, for example as an employee talking to her employer, you may use humble forms for yourself throughout.

9.2. Kinship terms

The terms used to refer to members of a family come in pairs: one neutral (also used for the humble situations ‘my…’) and the other exalted (‘your…’). For ‘his…,’ you would ordinarily use the exalted form, unless you consider the ‘him’ a member of your own in-group as contrasted with the person you are speaking to.

Neutral |

Exalted |

|

father |

父 chichi |

お父さん otōsan |

mother |

母 haha |

お母さん okāsan |

parent(s) |

両親 ryōshin |

ご両親 go-ryōshin |

sibling(s) |

兄弟 kyōdai |

ご兄弟 go-kyōdai |

son |

息子 musuko |

息子さん musukosan; 坊ちゃん botchan |

daughter |

娘 musume |

娘さん musumesan; お嬢さん ojōsan |

baby |

赤ちゃん aka-chan |

— |

child, children |

子ども kodomo |

子どもさん kodomosan; お子さん okosan |

older brother |

兄 ani |

お兄さん onīsan |

older sister |

姉 ane |

お姉さん onēsan |

younger brother |

弟 otōto |

弟さん otōtosan |

younger sister |

妹 imōto |

妹さん imōtosan |

grandfather |

祖父 sofu |

おじいさん ojīsan |

grandmother |

祖母 sobo |

おばあさん obāsan |

uncle |

おじ oji |

おじさん ojisan |

aunt |

おば oba |

おばさん obasan |

nephew |

甥 oi |

甥御さん oigosan |

niece |

姪 mei |

姪御さん meigosan |

cousin |

いとこ itoko |

おいとこさん o-itokosan |

relatives |

親戚 shinseki |

ご親戚 go-shinseki |

husband |

主人 shujin; 夫 otto |

ご主人 go-shujin |

wife |

家内 kanai; 妻 tsuma |

奥さん okusan |

family |

家族 kazoku |

ご家族 go-kazoku |

The words ojisan and obasan as well as ojīsan and obāsan are also used in a general way by young people to refer to anyone of an older generation, for example: tonari no ojisan ‘the man next door,’ ano obasan ‘that lady,’ and ano obāsan ‘that elderly lady.’

9.3. Other nouns

There are a few other nouns that come in pairs, with one neutral, the other exalted.

Neutral |

Exalted |

|

house, home |

うち uchi; 家 ie |

お宅 otaku |

person |

人 hito; 者 mono |

方 kata |

he, she |

あの人 ano hito |

あの方 ano kata |

how |

どう dō |

いかが ikaga |

where |

どこ doko |

どちら dochira |

who |

だれ dare |

どなた donata; どちら dochira |

9.4. Honorific prefixes

There are two common honorific prefixes, o- and go-. Words containing an honorific prefix may indicate an exaltation of the word itself, on its own merits, as in watashi no o-tomodachi ‘my friend’ and anata no o-tomodachi ‘your friend,’ or it may indicate the relationship between the word and an exalted person, as in o-niwa ‘your garden.’ Again, with nouns and verb forms, it may be just generally honorific, used for both humble and exalted situations. With adjective forms, the use of the honorific prefix seems always to indicate an exalted relationship: o-isogashii toki ‘at a time when YOU are very busy.’

The prefix go- is attached to a number of nouns (often, but not always, of Chinese origin) and to a few verb infinitives: go-shujin ‘your husband,’ go-yukkuri ‘slowly,’ go-zonji ‘knowing.’ The prefix o- is more widely used and is attached readily to nouns (including many of Chinese origin: o-shōyu ‘the soy sauce,’ o-denwa ‘the telephone’), verb infinitives (o-yasumi), and many adjectives (o-isogashii ‘busy’).

Some words by convention have the prefixes o- and go-, particularly in the speech of women and children, regardless of whether the situation calls for an honorific (humble or exalted) form or not. This is an extension of the usage exalting the word itself, on its own merits. Here is a list of some of these words with a conventional honorific prefix:

ご飯 go-han

cooked rice, meal, food

お米 o-kome

rice (uncooked, but harvested)

お酒 o-sake

rice wine

ご褒美 go-hōbi

reward, prize

お盆 o-bon

tray

お茶 o-cha

tea

お金 o-kane

money

お腹 o-naka

stomach

お菓子 o-kashi

pastry, sweets

お釣り o-tsuri

change

お湯 o-yu

hot water

9.5. Honorific suffixes for people’s names

There are two honorific suffixes for people’s names: -san and -sama. The latter is a formal variant of the former, usually restricted to certain set expressions. The suffix -san is widely used with names (= Mr., Miss, Ms., Mrs.), kinship terms, occupations, and other nouns referring to people. In more formal speech, -sama sometimes replaces -san in these terms. In more intimate speech, -chan is heard.

田中さん Tanaka-san

Mr. Tanaka

スミスさん Sumisu-san

Mr. Smith

陽子さん Yōko-san

Yoko

陽子ちゃん Yōko-chan

Yoko

マイケルさん Maikeru-san

Michael

社長さん shachō-san

president

お客さん o-kyaku-san ・お客様 o-kyaku-sama

customer, guest

9.6. Verbs: the honorific infinitive

The humble or exalted equivalent to a simple polite verb of neutral status is often an expression built around the HONORIFIC INFINITIVE. For verbs, this form is usually made by prefixing o- to the regular infinitive.

The most common honorific usage for verbs is as follows. For the humble form, use the honorific infinitive plus some form of the neutral verb suru ‘does’ or of the humble verb itasu ‘does.’ The forms with itasu show greater deference (= are more humble) than the forms with suru:

お書きいたします。/お書きします。

O-kaki itashimasu./O-kaki shimasu.

I’ll write it.

For the exalted form, use the honorific infinitive + the particle ni + some form of the verb naru ‘becomes.’

お書きになります。

O-kaki ni narimasu.

(He) will write it.

Some verbs such as kaeru ‘returns’ can be used with some form of the copula da or of the honorific polite copula de gozaimasu, or of the exalted copula de irassharu.

お帰りです。 O-kaeri desu.

(He) is returning.

お帰りでございます。 O-kaeri de gozaimasu.

(He) is returning.

お帰りでいらっしゃいます。 O-kaeri de irasshaimasu.

(He) is returning.

Other examples are:

お休みでございます。 O-yasumi de gozaimasu.

(He) is resting.

お出かけでございます。 O-dekake de gozaimasu.

(He) is out.

お探しでございます。 O-sagashi de gozaimasu.

(He) is looking (for it).

9.7. Special honorific verbs

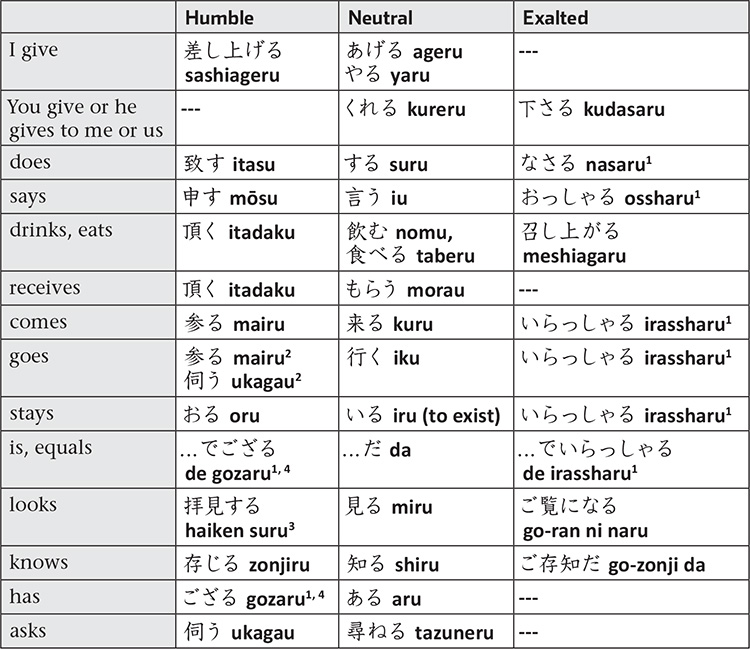

For many common verbs, in addition to (or to the exclusion of) regularly formed exalted and humble forms, Japanese use special verbs or special infinitives for either the exalted or the humble, or for both. In the table of special verbs below, the verbs are arranged in three vertical columns, humble, neutral, and exalted. Where there are blanks in the table, it means there is no special verb for the humble or for the exalted, but that the form can be made in the regular way (HONORIFIC INFINITIVE + itasu; HONORIFIC INFINITIVE + ni naru, etc.).

1 These verbs are consonant verbs, but り ri that appears directly before the polite suffix (ます masu, ません masen, etc.) changes to い i.

2 If the speaker is going to the place of the addressee, use 伺う ukagau rather than 参る mairu.

3 Use 拝見する haiken suru only if the item seen belongs to the addressee.

4 ござる gozaru and … でござる de gozaru function either as humble forms or very polite forms.

9.8. 申し上げる mōshiageru

The verb mōshiageru is used as a humble form for either ‘does’ or ‘says’:

またお伺い申し上げます。=またお伺いいたします。

Mata o-ukagai mōshiagemasu. = Mata o-ukagai itashimasu.

I’ll visit you again.

申し上げたいことがございます。= 申したいことがございます。

Mōshiagetai koto ga gozaimasu. = Mōshitai koto ga gozaimasu.

There’s something I want to tell you.

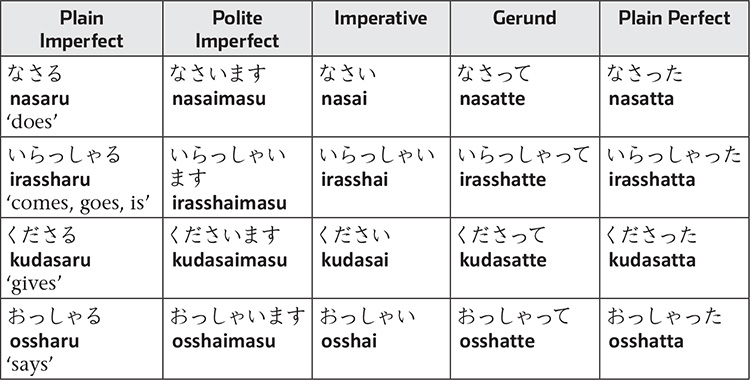

9.9. Inflection of slightly irregular exalted verbs

The verbs nasaru, irassharu, kudasaru, and ossharu are irregularly inflected in similar ways:

For gozaru (gozaimasu) see 9.15.

9.10. Special inflections of - ます -masu

The polite ending -masu is really itself a verb that is used only when attached to other verb infinitives. In ordinary polite speech it is inflected only for the imperfect -masu, the perfect -mashita, and the tentative -mashō. But in honorific speech, -masu is inflected for all categories except the infinitive. These polite forms are used at the end of sentence fragments, and also in the middle of sentences instead of the usual plain forms, to make the entire expression a bit more honorific:

そこへいらっしゃいまして

Soko e irasshaimashite…

You go there and…

そこへいらっしゃいましたら

Soko e irasshaimashitara…

If you go there …

そこへいらっしてくださいませ。

Soko e irasshite kudasaimase.

Please go there.

Here are the inflections of the polite verb -masu:

Imperfect: -masu

Tentative: -mashō

Infinitive: --

Provisional: -maseba

Imperative: -mase

Perfect: -mashita

Alternative: -mashitari (10.5)

Gerund: -mashite

Conditional: -mashitara

You may also encounter deshite, a polite gerund for the copula ‘is and’:

スキー王と呼ばれた人でして,関西に初めてスキー場を開いた人でした。

“Sukī-ō” to yobareta hito deshite, Kansai ni hajimete sukī-jō o hiraita hito deshita.

He was the man they called the “Ski King,” and the one that opened the first ski resort in Kansai.

9.11. Use of humble verbs

In general, humble verbs are used to denote one’s own acts when speaking to persons who are socially superior.

「部長,ちょっとお伺いしても宜しいですか。」

“Buchō, chotto o-ukagai shite mo yoroshii desu ka.”

“(Manager,) is it okay to ask you something?”

「ええ,何?」

“Ē, nani?”

“Sure, what?”

When two people of approximately equal social status are talking, each may use the exalted forms in reference to the other person, but they generally use just the simple polite forms rather than the humble forms in reference to themselves.

「どこへいらっしゃいますか。」

“Doko e irasshaimasu ka.”

“Where are you going?”

「銀行へ行きます。」

“Ginkō e ikimasu.”

“I’m going to the bank.”

An exception to this occurs when the verb implies participation of the other person or some person of higher social status as fellow-subject, indirect or direct object, possessor of something involved in the action, etc.; in this case, the humble form is customary. Sometimes, however, the humble form may be used by both speakers.

「どこへいらっしゃいますか。」

“Doko e irasshaimasu ka.”

“Where are you going?”

「田中先生のお宅へ参ります。」

“Tanaka sensei no otaku e mairimasu.”

“I’m going to Professor Tanaka’s house.”

9.12. Adjectives and adjectival nouns

An adjective used as a modifier before a noun or noun phrase either remains unchanged or just adds the honorific prefix o-: o-isogashii toki ‘a busy time (for you).’ When an adjective is used at the end of a sentence as the main predicate, it may be treated in one of two ways: as an exalted expression, or as a general honorific (exalted or humble) expression. It is usually treated as an exalted expression IF THE REFERENCE IS DIRECTLY TO THE PERSON YOU ARE TALKING WITH or TO SOMEONE ELSE OF HIGH SOCIAL STATUS. Otherwise, if the reference is to one of his possessions, or to someone else of equal social status, or to yourself, it is treated as a general honorific.

The exalted expression is made by using the gerund (-kute) form of the adjective, with the honorific prefix o-, followed by some form of the exalted verb irassharu ‘stays, exists’:

お忙しくていらっしゃいます。

O-isogashikute irasshaimasu.

You are busy.

Similarly, adjectival nouns can be preceded by o and followed by de and irassharu.

山田さんはいつもおきれいでいらっしゃいますね。

Yamada-san wa itsu mo o-kirei de irasshaimasu ne.

Ms. Yamada is always pretty.

9.13. Formation of the adjective honorific infinitive

If we include the vowel that appears before the imperfect ending -i, Japanese adjectives are of four types: -ii, -ai, -oi, and -ui (ōkii, akai, aoi, warui). To produce the honorific infinitive form, we have to change not only the ending, but also the vowel before the ending, as follows:

Imperfect |

Honorific Infinitive |

Neutral Infinitive |

-ii |

-yū |

-iku |

-ai |

-ō |

-aku |

-oi |

-ō |

-oku |

-ui |

-ū |

-uku |

Here are some examples of adjective expressions in the plain, polite, and honorific imperfect:

Meaning |

Plain |

Polite |

Honorific |

is satisfactory |

よろしい yoroshii |

よろしいです yoroshii desu |

よろしゅうございます yoroshū gozaimasu |

is red |

あかい akai |

あかいです akai desu |

あこうございます akō gozaimasu |

is early |

はやい hayai |

はやいです hayai desu |

はようございます hayō gozaimasu |

is white |

しろい shiroi |

しろいです shiroi desu |

しろうございます shirō gozaimasu |

is slow, late |

おそい osoi |

おそいです osoi desu |

おそうございます osō gozaimasu |

is thin |

うすい usui |

うすいです usui desu |

うすうございます usū gozaimasu |

is good |

いい, よい ii, yoi |

いいです ii desu |

ようございます yō gozaimasu |

Note that this form is old-fashioned, and is used only in quite formal contexts or by elderly people.

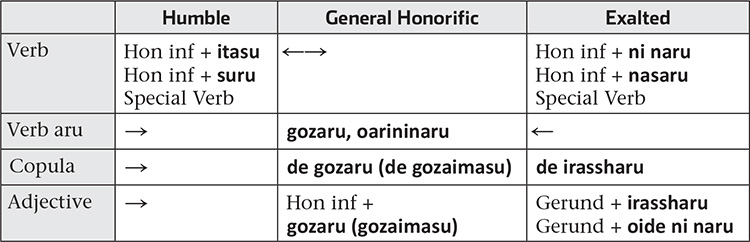

9.14. Summary of honorific predicates

9.15. ござる gozaru

The verb gozaru is the honorific equivalent of the neutral verb aru ‘exists’; it is neither specifically humble nor specifically exalted, just generally honorific. In modern speech it never actually occurs in any plain forms—you don’t hear gozaru. You hear gozaimasu in set phrases and within a sentence:

おはようございます。 O-hayō gozaimasu.

Good morning.

ありがとうございます。 Arigatō gozaimasu.

Thank you.

申し訳ございません。 Mōshiwake gozaimasen.

I’m terribly sorry.

お金がございましたら寄付をお願いいたします。

O-kane ga gozaimashitara kifu o o-negai itashimasu.

If you have the money, please donate some for us.

沢山ございますから, どうぞご遠慮なさらないでください。

Takusan gozaimasu kara, dōzo go-enryo nasaranai de kudasai.

Because there’s lots, please don’t feel shy (i.e. about helping yourself).

Gozaimasu is also used after the honorific infinitive form of the adjective as in Takō gozaimasu ‘It is expensive.’ (See 9.13)

Just as gozaimasu (gozaru) is the general honorific equivalent of the neutral verb aru, the expression de gozaimasu (de gozaru) is the general honorific equivalent of the copula da. For example:

4階でございます。

Yon-kai de gozaimasu.

It’s the fourth floor.

9.16. いらっしゃる irassharu

The exalted verb irassharu corresponds to three different neutral verbs: kuru ‘comes,’ iku ‘goes,’ and iru ‘stays, exists.’ As with all homonyms, you can usually tell which meaning is intended by the context:

どちらからいらっしゃいましたか。

Dochira kara irasshaimashita ka.

Where did you come from?

どちらへいらしゃいましたか。

Dochira e irasshaimashita ka.

Where did you go?

お母様はどちらにいらっしゃいますか。

Okāsama wa dochira ni irasshaimasu ka.

Where is your mother?

9.17. おいで oide

The expected forms for the honorific infinitives of kuru ‘comes,’ iku ‘goes,’ and iru ‘stays, exists,’ which are oki, oiki, and oi, rarely occur. Instead, for the exalted form you use either the special exalted infinitive oide (+ ni naru, etc.) or the exalted verb irassharu.

どちらからおいでになりましたか。

Dochira kara oide ni narimashita ka.

Where did you come from?

どちらへおいでになりましたか。

Dochira e oide ni narimashita ka.

Where did you go?

お母様はどちらにおいでになりますか。

Okāsama wa dochira ni oide ni narimasu ka.

Where is your mother?

9.18. Verbs for giving and receiving

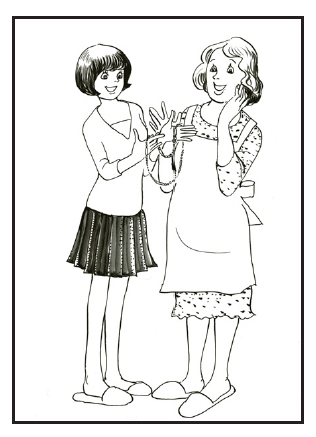

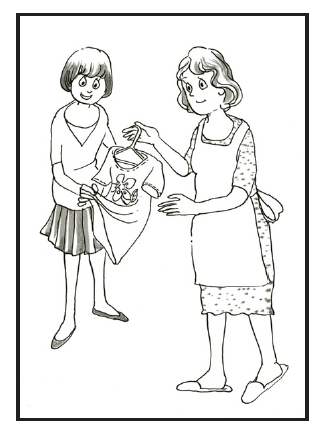

The verbs ageru and kureru both mean ‘to give.’ The choice between the two depends on how close the speaker feels to the giver and the recipient. The verb kureru is used only when the recipient is the speaker’s insider, and the recipient is closer to the speaker than the giver. In all other contexts, ageru is used. For example, in the following sentences, the recipients are the speaker’s “insiders” (the speaker or the speaker’s family members), the recipients are closer to the speaker than the giver, and the verb kureru is used.

ジョンさんが私にチョコレートをくれました。

Jon-san ga watashi ni chokorēto o kuremashita.

John gave me chocolate.

ジョンさんが母にチョコレートをくれました。

Jon-san ga haha ni chokorēto o kuremashita.

John gave my mother chocolate.

母が私にチョコレートをくれました。

Haha ga watashi ni chokorēto o kuremashita.

My mother gave me chocolate.

*Watashi ga haha ni chokorēto o kuremashita ‘I gave my mother chocolate’ is UNGRAMMATICAL because the recipient is less close to the speaker than the giver, although the recipient is the speaker’s insider. Once kuremashita is replaced by agemashita, as in Watashi ga haha ni chokorēto o agemashita, the sentence becomes grammatical. When the giving event takes place among the speaker’s insiders, excluding the speaker himself, either ageru or kureru can be used. If kureru is used, it shows that the speaker feels closer to the receiver than to the giver. When the giving event takes place among outsiders, ageru is generally used.

The verb ageru must be replaced by sashiageru when the receiver is socially superior to, and/or distant from, the giver:

私は先生にチョコレートを差し上げました。

Watashi wa sensei ni chokorēto o sashiagemashita.

I gave the teacher chocolate.

父は社長にチョコレートを差し上げました。

Chichi wa shachō ni chokorēto o sashiagemashita.

My father gave the president chocolate.

The verb kureru must be replaced by kudasaru when the giver is socially superior to, and/or distant from, the receiver.

先生は私にチョコレートを下さいました。

Sensei wa watashi ni chokorēto o kudasaimashita.

The teacher gave me chocolate.

社長は父にチョコレートを下さいました。

Shachō wa chichi ni chokorēto o kudasaimashita.

The president gave my father chocolate.

Note that the verb kudasaru is a consonant verb, but its masu-form is kudasaimasu rather than kudasarimasu.

The verb ageru can be optionally replaced by yaru when the receiver is socially in a lower status than the giver. For example, when you are giving something to your younger siblings, children, or pets, you can use yaru instead of ageru:

子どもにチョコレートをやりました。

Kodomo ni chokorēto o yarimashita.

I gave chocolate to my children.

For the meaning ‘to receive,’ you can use morau or its honorific version itadaku. The receiver must be closer to the speaker than to the giver when using these verbs. The source of receiving is marked by the particle kara or ni.

私は父に時計をもらった。

Watashi wa chichi ni tokei o moratta.

I received a watch from my father.

母は隣の方からケーキを頂いた。

Haha wa tonari no kata kara kēki o itadaita.

My mother received cakes from our next-door neighbor.

9.19. Favors

When you say ‘someone does something FOR someone else,’ you are reporting a FAVOR. To do this in Japanese, use the gerund of the verb representing the action of the favor, and then add on the appropriate verb meaning ‘gives.’ In other words, to say ‘I’ll write the letter for you,’ the Japanese says something like ‘I will give you (the favor of) writing the letter,’ Tegami o kaite agemasu. The person doing the favor is either the topic, followed by the particle wa, or the emphatic subject, followed by the particle ga. The person for whom the favor is done is indicated by the particle ni:

田中さんは中村さんに手紙を書いてあげました。

Tanaka-san wa Nakamura-san ni tegami o kaite agemashita.

Mr. Tanaka wrote the letter to Mr. Nakamura.

The verbs for giving are used just as they would be if you were giving some object instead of a favor. Similarly, the verbs of receiving can also be used for this function. Make sure to mark the recipient of the kind action with the particle ni.

兄は私に本を読んでくれました。

Ani wa watashi ni hon o yonde kuremashita.

My brother read a book to me.

先生は私に漢字を教えてくださいました。

Sensei wa watashi ni kanji o oshiete kudasaimashita.

My teacher taught me kanji.

私は犬にセーターを作ってやりました。

Watashi wa inu ni sētā o tsukutte yarimashita.

I made a sweater for my dog.

先生に推薦状を書いていただきました。

Sensei ni suisenjō o kaite itadakimashita.

I had my teacher write a letter of recommendation for me.

9.20. Requests

The Japanese do not use imperative forms as often as we do. There are several ways to make a polite request in Japanese. You can use gerund forms or honorific infinitive along with some forms of verbs of giving and receiving. The expressions ending in a verb of giving (e.g. kudasai) are quite straightforward and might be too plain in a polite context. The politeness increases if the expression takes the form of a negative question (…masen ka), because this would make it sound more indirect. Furthermore, it sounds more polite if you use a verb of receiving (morau/itadaku) rather than a verb of giving, in the potential form (moraeru/itadakeru) in a negative question, as in moraenai deshō ka, itadakemasen ka or itadakenai deshō ka. The following sentences all express the request ‘Please read this letter.’

この手紙を読んでください(ませんか)。

Kono tegami o yonde kudasai(masen ka).

この手紙をお読みください。

Kono tegami o o-yomi kudasai.

この手紙を読んでもらえませんか。

Kono tegami o yonde moraemasen ka.

この手紙を読んでいただきたいんですが。

Kono tegami o yonde itadaki-tai n desu ga.

この手紙を読んでいただけないでしょうか。

Kono tegami o yonde itadakenai deshō ka.

Negative requests are not ordinarily made except in the form of prohibitions to inferiors: Itsu mo o-kashi o tabete wa ikemasen yo ‘You mustn’t eat sweets all the time.’ To a social equal or superior, you suggest that ‘it would be better not’ to do something: Sore o tabenai hō ga ii deshō ‘It would be better if you didn’t eat that.’ Or, given two alternatives, you emphasize the positive one: Sore o tabenai de, kore o tabete kudasai ‘Please eat this one instead of that one.’

9.21. Answers to negative questions

The words hai (or ē) and īe are used to mean ‘what you’ve said is correct’ and ‘what you’ve said is incorrect.’ So if you state a question in a negative way, the standard Japanese answer turns out to be the opposite of standard English ‘yes’ and ‘no,’ which affirm or deny the FACTS rather than the STATEMENT of the facts.

「砂糖はいりませんか。」

“Satō wa irimasen ka.”

“Don’t you need sugar?”

「はい,いりません。」

“Hai, irimasen.”

“Correct, I don’t need it.”

「バナナはありませんか。」

“Banana wa arimasen ka.”

“Do you have no bananas?”

「はい,バナナはありません。」

“Hai, banana wa arimasen.”

“Correct, we have no bananas.”

Of course, if the negative question is really just an oblique request, then you indicate assent with hai and your refusal with īe, as you would in English.

「スーツケースを持ってきてくださいませんか。」

“Sūtsukēsu o motte kite kudasaimasen ka.”

“Won’t you please bring the suitcase over here?”

「はい,かしこまりました。」

“Hai, kashikomarimashita.”

“Yes, gladly.

「もう少し召し上がりませんか。」

“Mō sukoshi meshiagarimasen ka.”

“Won’t you have a little more

(to eat)?”

「いいえ,もう結構です。」

“Īe, mō kekkō desu.”

“No, thanks.”

9.22. The specific plural

In general, singular and plural are not distinguished in Japanese: hon means ‘book’ or ‘books’ and kore means ‘this’ or ‘these.’ There are, however, ways to make specific plurals for certain nouns, and these are in common use, particularly for the equivalents of English pronouns. There is the following set of suffixes:

HUMBLE

-ども -domo

NEUTRAL

-たち -tachi

EXALTED

-方 -gata

These occur in the following combinations:

私たち wata(ku)shi-tachi

we (neutral)

私ども wata(ku)shi-domo

we (honorific = humble)

あなたたち anata-tachi

you all (neutral)

あなた方 anata-gata

you all (honorific = exalted)

あの人たち ano hito-tachi

they (neutral)

あの方々 ano katagata

they (honorific = exalted)

The suffix -tachi is used frequently with nouns indicating people: gakusei-tachi ‘students,’ Tanaka-tachi ‘Tanaka and his group,’ and kodomo-tachi ‘children.’ Unless used impersonally, such expressions seem rather impolite. They can be made more polite by adding -san before -tachi, as in gakusei-san-tachi, Tanaka-san-tachi, kodomo-san-tachi. If special deference is shown to the people discussed, the exalted suffix -gata is used: sensei-gata ‘teachers.’ Both hitotachi and hitobito are used to mean ‘people.’ Reduplications of the hitobito type often include a connotation of variety or respective distribution ‘various people.’ Other examples are kuniguni ‘various countries,’ shimajima ‘(various or numerous) islands, island after island,’ and sorezore ‘severally, variously, respectively.’

The words kore, sore, and are refer to both singular and plural, ‘this’ or ‘these,’ ‘that’ or ‘those.’ They can be made specifically plural by adding the suffix -ra: korera ‘these,’ sorera ‘these,’ and arera ‘those over there.’ But in a simple equational sentence like ‘These are roses, and those are camellias’ you just use the plain forms Kore wa bara de, sore wa tsubaki desu.

Another polite way to say ‘you (all)’ is mina-san or mina-san-gata. The word mina-san is often heard at the beginning of a public talk, equivalent to English ‘Ladies and Gentlemen.’ Sometimes it means just ‘everybody (at your house)’ as in Mina-san ni yoroshiku ‘Please give my regards to everyone.’

|

[cue 09-3] |

Conversation

Christopher (C) wants to apply for a graduate school in Japan, and he needs a letter of recommendation. He thought of asking his Japanese teacher (T).

C: 来年から大学院で言語学を勉強したいと思っているんです。

Rainen kara daigakuin de gengogaku o benkyō shitai to omotte iru n desu.

I’m thinking of studying linguistics at a graduate school starting next year.

T: ああ,それはいいですね。

Ā, sore wa ii desu ne.

Oh, that’s great!

C: はい。それで1つお願いがあるんですが。

Hai. Sore de hitotsu o-negai ga aru n desu ga.

Right. And I have a favor to ask you.

T: はい。何でしょう。 Hai. Nan deshō. Sure. What’s that?

C: 推薦状を書いていただけないでしょうか。

Suisenjō o kaite itadakenai deshō ka.

Could you write a letter of recommendation for me?

T: もちろんいいですよ。 Mochiron ii desu yo. Of course, I’d be glad to.

C: ああ,どうもありがとうございます。

Ā, dōmo arigatō gozaimasu.

Oh, thank you so much!

T: いつまでに要りますか。 Itsu made ni irimasu ka. By when do you need it?

C: 来月の終わりまでにお願いできますでしょうか。

Raigetsu no owari made ni onegai dekimasu deshō ka.

Could you write it by the end of next month?

T: ええ, 大丈夫です。 Ē, daijōbu desu. Sure, no problem.

C: ああ,ありがとうございます。お忙しいところ申し訳ございませんが, どうぞ宜しくお願いいたします。

Ā, arigatō gozaimasu. O-isogashii tokoro mōshiwake gozaimasen ga, dōzo yoroshiku o-negai itashimasu.

Oh, thank you very much. I’m terribly sorry to ask this when you are busy, but your help is very much appreciated.

Exercises

I. Fill in the blanks with appropriate verbs of giving or receiving.

1. 私は母にネックレスを ———————— 。

Watashi wa haha ni nekkuresu o ———————— .

2. 母は私にTシャツを ———————— 。

Haha wa watashi ni tīshatsu o ———————— .

3. 私は母からTシャツを ———————— 。

Watashi wa haha kara tīshatsu o ——————— .

4. 私は先生にワインを ———————— 。

Watashi wa sensei ni wain o ———————— .

5. 母は隣の方にお菓子を ———————— 。

Haha wa tonari no kata ni o-kashi o ———————— .

6. 田中さんは兄にネクタイを ———————— 。

Tanaka-san wa ani ni nekutai o ———————— .

7. 兄は田中さんからネクタイを ———————— 。

Ani wa Tanaka-san kara nekutai o ———————— .

II. Match the words in Box A with the words in Box B.

Box A i. ありました arimashita ii. くれました kuremashita iii. しました shimashita iv. 来ました kimashita v. 言いました iimashita |

Box B a. なさいました nasaimashita b. くださいました kudasaimashita c. おっしゃいました osshaimashita d. いらっしゃいました irasshaimashita e. ございました gozaimashita |

III. Select the best choice.

1. 先生,どうぞ ——————— ください。

Sensei, dōzo ——————— kudasai.

a. 召し上がって meshiagatte

b. 頂いて itadaite

c. 食べて tabete

d. 食べに tabeni

2. 先生, あの本はもう ———————— 。

Sensei, ano hon wa mō ———————— .

a. お読みしましたか o-yomi shimashita ka

b. お読みなりましたか o-yomi narimashita ka

c. お読みになりましたか o-yomi ni narimashita ka

d. お読みいたしましたか o-yomi itashimashita ka

3. 私が ———————— 。

Watashi ga ———————— .

a. お書きします o-kaki shimasu

b. お書きになります o-kaki ni narimasu

c. お書きなさいます o-kaki nasaimasu

d. お書きにいたします o-kaki ni itashimasu

4. 僕の ———————— は石田さんの ———————— とよく話します。

Boku no ———————— wa Ishida-san no ———————— to yoku hanashimasu.

a. 奥さん okusan, ご主人 go-shujin

b. 主人 shujin, 奥さん okusan

c. 家内 kanai, 奥さん okusan

d. 家内 kanai, 主人 shujin

5. この手紙を読んで ———————— 。

Kono tegami o yonde ———————— .

a. お願いします onegai shimasu

b. いただけませんか itadakemasen ka

c. くださいございます kudasai gozaimasu

d. なさいます nasaimasu