4

APRIL 6, FORENOON—GRANT

“I Think It’s at Pittsburg”

Ever after, Grant and Sherman would insist it was no surprise. For the rest of their lives, they would point to the continual skirmishes with Confederate units for days beforehand as proof that they had seen the attack coming. They would add, with similar truth, that they made defensive adjustments almost up to the moment it began.

1

But their Federals had not entrenched. To have done so would have bucked the judgment of General Charles Ferguson Smith, Grant’s mentor-friend and one of the top officers of the prewar army. Gruff old Smith had scoffed at fortifying. Attack, indeed; he growled that he only wished the Confederates would. He may even have meant to invite them to. Before Grant arrived, Smith had planned to order Sherman’s and Lew Wallace’s divisions to that vulnerable west bank of the Tennessee, where the Corinth-congregating Confederates could get at them without having to cross the river. So Grant had gone ahead and ordered them there. “We can whip them to hell,” Smith said.

2Sherman chose the Pittsburg Landing campsite for another credible reason that Smith doubtless considered. In this spring flood season, much of the ground along the Tennessee was inundated, but the road up from Pittsburg Landing rose onto a low, broad plateau that was comparatively dry and well drained.

Brigadier Bull Nelson’s hard-marching division of Don Carlos Buell’s army arrived at Grant’s headquarters in Savannah, on the river’s east side, on April 5. His mind on the offensive, Grant rebuffed Nelson’s anxiety and directed him to bivouac on the east bank for a couple of days. Boats to ferry Nelson’s men down to Hamburg Landing were scarce, he explained. No need to hurry.

3Despite Smith’s cockiness, Grant had shown some intent to follow Major General Henry Halleck’s cautionary directives. He ordered his chief engineer, Lieutenant Colonel James B. McPherson, to mark out a trench line at Pittsburg Landing. But when it turned out to run behind some bivouacs already established near water, Grant did not order the sites changed.

Other adjustments may have been in abeyance pending the arrival of Buell and Halleck. Halleck had ordered Grant to bring on no battle, so Grant and his division commanders ignored the increasing Confederate provocations. And more permanent fortifications were not thrown up, most likely, because doing so ran contrary to Grant’s aggressive nature. He expected to move toward Corinth as soon as Halleck arrived.

4Thus, most of Grant’s and Sherman’s reasons for their professed lack of surprise were intellectually dishonest. They correctly maintained that the sight of Confederates at Pittsburg Landing on April 6 was not unexpected. The sight of so many, however, was.

Many Federal officers and men did not share the Smith-Grant confidence. Several subordinate Union colonels were as convinced that they were about to be attacked as Sherman claimed to doubt it.

Sherman scoffed at their concerns. The Confederates would never come out of their fortified base and attack the Federals in theirs, he asserted, echoing Grant and Smith. Getting angry, he went out of his way to humiliate the nervous colonels, telling one to “take your damn regiment back to Ohio” and court-martialing another. He insisted that the parties of Confederates were just reconnoitering.

5Union pickets sensed otherwise. Since April 3, they had seen growing numbers of enemy cavalry watching them from behind trees and bushes. Colonel Everett Peabody, brigade commander in the division to the left front of Sherman’s, disobeyed an order from Brigadier General Benjamin M. Prentiss. Prentiss had told some Peabody pickets to pull back and not to be alarmed by the sound of widespread movements in the woods around them after dark on the night of April 5. Before dawn on April 6, Peabody sent out five companies to try to capture and interrogate some of the “prowling” Confederates.

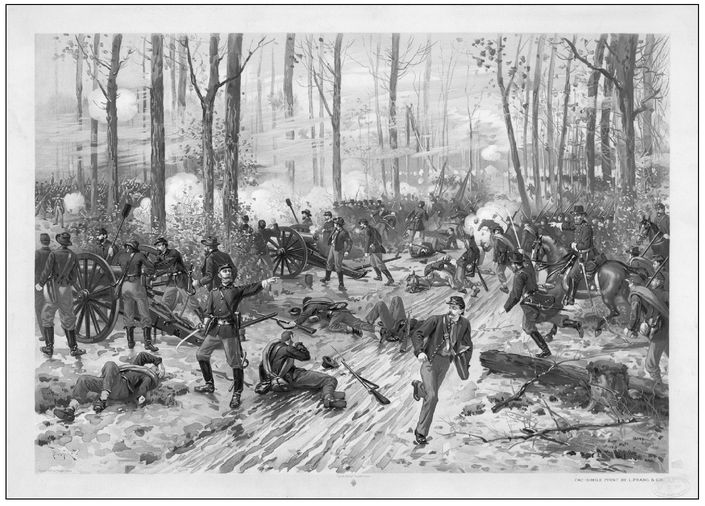

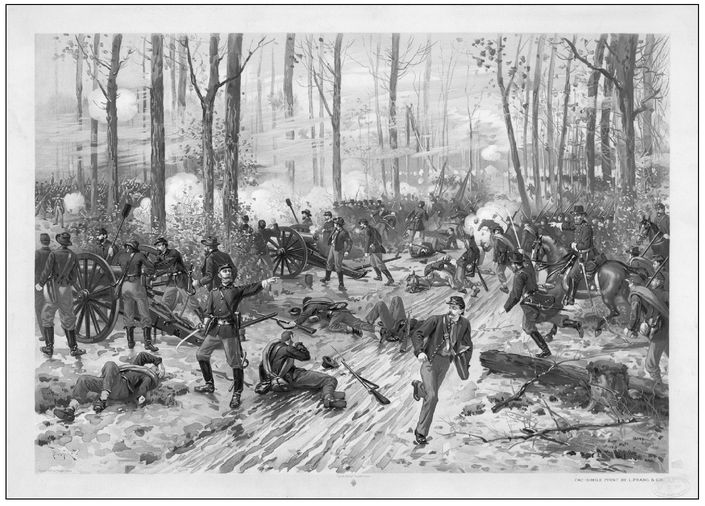

6

BATTLE OF SHILOH

The party soon encountered the enemy. They traded volleys for an hour, but the Confederates were so numerous that the Federals pulled back, dragging dead and wounded, as day dawned. Prentiss meanwhile heard heavy firing growing louder and ordered his division into line, then hurried it a quarter mile forward. There, at about 6:30 a.m., just after meeting his retiring pickets, he ran head-on into the center of Albert Sidney Johnston’s army.

Confederates and Federals began firing as fast as they could reload, but Prentiss was overmatched. Colonel Francis T. Quinn of the Twelfth Michigan Infantry saw an enemy line in his front stretching right and left, “and every hill-top” behind that line “was covered with them.” The sight was more than daunting.

7Prentiss’s men, new to combat, retreated to their camp, then through it. Dodging between tents, they lost formation, as well as many of their number, some falling to Confederate fire and more sprinting for the rear.

At about 7 a.m., Sherman, still skeptical, rode toward the increasing clamor. He was looking through his binoculars and deciding that this was indeed a sharp skirmish when Confederates burst from the undergrowth to his right and shot an aide dead beside him. Belatedly, he realized—and shouted—the truth: “We are attacked!” He threw up his right hand to shield himself and took a shot in it. Ordering Colonel Jesse Appler of the Fifty-third Ohio to stand his ground, Sherman galloped off for reinforcements.

Appler was the officer Sherman had told the day before to take his regiment back to Ohio. He now appeared eager to comply. Under assault by the Sixth Mississippi, Appler went to pieces. His troops were so decimating the Mississippians with cannon and musket fire that only a minority of the Sixth’s 425 men remained unhurt, but Appler suddenly shouted, “Retreat and save yourselves.” The Fifty-third Ohio broke and fled in disorder through the Fifty-seventh, which Sherman had just sent to Appler’s aid. Some of the Fifty-third rallied and stayed on the field, along with—briefly—Appler. But soon, dismayed by his officers’ refusal to obey his fearful commands, he fled.

8Despite Appler’s personal skedaddle, the Ohioans drew a lot of blood. The Fifty-third and Fifty-seventh had managed to mangle two regiments commanded by Colonel Patrick R. Cleburne, the Irish immigrant and foster Arkansan destined to become perhaps the hardest-fighting infantry commander in the western Confederate armies. The bloodshed seems to have been overwhelmingly in the Ohioans’ favor. Sherman later claimed Appler’s line broke after losing but two enlisted men and no officers.

9

William T. Sherman had some excellent traits—high intelligence in particular—but a placid, steady nature was not one of them. This perhaps owed to his boyhood experience of his father’s death, which shattered his world and thrust him into a foster family. That wrenching experience was reinforced in adulthood by a number of life’s capricious twists of fate. He often seemed to lack self-confidence and, as if trying to shore it up, overcompensated with boisterous, often outrageous talk. His contemptuous dismissal of the threat of Confederate attack at Shiloh was typical.

In private, Sherman may not have been so sure there was no danger. His professed skepticism was perhaps a desperate attempt to quell his own growing apprehensions. Although he had spent thirteen years in the army, he had seen no antebellum combat. The Seminole War in Florida had been a simmering thing that afforded him no opportunity to bleed, shed blood, or experience battle, and during the Mexican War, he had served in California, even farther from the fighting.

10Once this new and much larger war began, though, Sherman showed that fear of losing his own life was not his problem. He had led men in combat at Bull Run, was grazed twice by bullets there, and had a horse killed under him. He trembled only for his country. He had long doubted the national will to reunite the states, as well as his—or anybody else’s—capacity to do anything about the looming cataclysm. His problem was more one of ambivalence than fear. Although Southerners would come to hate his name, he felt affection for them. He despised abolitionists for tearing the nation apart, shared Dixie society’s extreme racial animus, and thought Southerners and the South all but impossible to defeat.

Yet, he remained unionist to the bone. At the advent of secession, he had been in the second year of his prewar life’s most fulfilling job as inaugural superintendent of the future Louisiana State University. But when Louisiana troops took over the Federal arsenal in Baton Rouge, he resigned. He felt beholden to the Union for his West Point education.

11Sherman had brought a division of “perfectly new” volunteers, as he called them, to these camps around Shiloh Church, and he had seen little in this war to assure him of their competence. He had watched mobs of volunteers flee the Confederate guns at Bull Run. Given command in the state of Kentucky, he had insisted he needed 200,000 such volunteers to prevent Confederates from overrunning the whole Midwest. The figure seemed huge so early in the war. When, as a result, newspaper headlines pronounced him insane, he requested to be relieved of the Kentucky assignment and was granted transfer. That bitter memory influenced him in the run-up to Shiloh. If he agreed with his fearful colonels, he told someone on April 5, “they’d say I was crazy again.”

Nobody could call him that, though, when he agreed with the colonels the next morning.

12

Around 7 a.m. the Confederates overran the Union camps “yipping and yelping,” as one Federal remembered. Many of the erstwhile campers bolted. The hundreds of fugitives began a gradual exodus that would swell into the thousands as many fled as far as they could without drowning: to and under the overhanging banks of the Tennessee River.

13

Grant’s unreadiness for a wholesale assault did not stem from lassitude. For three weeks he had pushed to visit on the Confederates what they had come here to visit on him: destruction. While gathering intelligence about the Southerners massing at Corinth, he had dispatched an aide, Captain W. S. Hillyer, to St. Louis to beseech Halleck to let him assail Johnston’s army before it was ready. Just that morning, April 6, Hillyer had returned. Grant’s plea had been rejected out of hand. Bring on no battle, Halleck reiterated.

14Now, over an early breakfast at Savannah, Grant heard the fighting nine miles away. He had been awaiting Buell’s arrival for a talk; otherwise, he would have left already for Pittsburg Landing, where he had planned to move his headquarters that day. On April 4, he had received word that the Senate had confirmed two of his subordinates, John McClernand and Lew Wallace, as major generals. That would make the grasping McClernand the ranking officer at Pittsburg Landing, surpassing Sherman, unless Grant went there himself. So Grant decided to do that. Buell, sulky as when he and Grant had met in Nashville in late February, had arrived in Savannah the previous evening, April 5. But he did not inform Grant, indicating continuing reluctance to coopperate.

15Buell had still not reported in when, a few minutes past 7:00, everybody at Grant’s breakfast table lapsed into silence at the alarming sound coming from the southwest. Chief of Staff Joseph D. Webster stated the obvious. “That’s firing.” An orderly rushed in and said the sound was coming from upriver. Everybody went to the door. “ Where is it?” Webster asked. “At Crump’s or Pittsburg?”

“I think it’s at Pittsburg,” Grant said. He was on crutches; the ankle sprained in the horse fall in the thunderstorm thirty-six hours earlier was swollen and throbbing. He leaned against Webster to strap on his sword, and everybody headed for the steamboat

Tigress. The craft’s engines were already running in preparation for the staff’s expected departure that morning.

16Before leaving, Grant wrote three messages, two to division chiefs of Buell’s army. Bull Nelson, whom Grant had so casually told to stay on the Tennessee’s east side, was now ordered to march down that bank to a point opposite Pittsburg Landing and ferry across from there. Brigadier General Thomas J. Wood should hurry his men to Savannah and march them onto Pittsburg-bound steamboats. The third dispatch informed Buell that Grant could not wait longer in Savannah for their meeting.

17Grant headed upriver probably between 7:15 and 7:30. Before 8:00, six miles north of Pittsburg, he ordered the

Tigress to run in close to Crump’s Landing. There Lew Wallace paced the deck of another boat. The two briefly conferred. Grant told Wallace to get his division ready; instructions would be coming.

18Likely between 8:00 and 8:30,

Tigress nosed into Pittsburg Landing under a thundering din from the plain above. A handful of stragglers clustered nearby. The lame major general strapped his crutch rifle-like to his saddle and rode upward toward the roar of the battle. Finding two newly arrived regiments of Iowans, he ordered them into line above the bluff. They were to stop further stragglers from retreating and organize them into makeshift units to return to the fight.

19Grant next ordered wagons of ammunition collected to go to the front, then headed there himself. Arriving, he found his engineer, Lieutenant Colonel McPherson, holding the command together as well as possible. The situation was grim. The most advanced Union line—a brand-new, totally green division under Brigadier General Prentiss—had initially been located two miles southwest of Pittsburg Landing. Most of Prentiss’s 5,400 men had fallen back nearly half that distance during the early morning, more than 1,000 of them becoming casualties. To the left, Brigadier General Stephen A. Hurlbut’s division began pulling back and trying to slow the Confederate steamroller that thinned, then at around 9:00 stampeded, much of Prentiss’s unit. To the right, Sherman and McClernand retreated too, but more deliberately.

20Then fate aided Prentiss’s remaining 2,000 troops and the Hurlbut units they were falling back on. As they overran the Federal camps, the famished Confederates stopped to bolt food they found there. This gave the mingling Prentiss and Hurlbut units time to reform a remnant along a farm lane. Years of travel by animals and wagons had slightly depressed its bed, and it lay amid a thicket fronted and flanked by open fields. Later exaggeratingly dubbed the Sunken Road, this path linked McClernand on Prentiss’s right and Sherman, even farther to the right, with Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, and Missouri units to the left between Prentiss and the Tennessee River. The depression and its fierce defense would on this day earn another name honoring its flying bullets: the Hornet’s Nest.

21People who saw Grant that morning detected no great concern. Having assured himself that the Pittsburg Landing attack was no feint preceding a knockout blow aimed at Crump’s, he sent a message to Lew Wallace to bring his division from there. He also wrote another message to Bull Nelson: “You will hurry up your command as fast as possible. The boats will be in readiness to transport all troops of your command across the river. All looks well, but it is necessary for you to push forward as fast as possible.” When aide William Rowley asked if things were not looking “squally,” Grant demurred. “Well, not so very bad,” he said. Wallace would surely be along soon.

22The Federal line was still receding at 10 a.m. as Grant rode to the right. There he found Sherman embattled, his right hand wrapped in bloody cloth. But Sherman was not his normal nervously excited self. Battle seemed to calm and focus him. With those of his men who had not run, he was trying to fight his way back to the church. He told Grant he needed more ammunition. Grant said wagonloads of it were coming and complimented the performance of Sherman’s green troops.

Grant wheeled away to gallop to points more needful of personal direction. “I never deemed it important to stay long with Sherman,” he would write afterward. He visited and revisited his other corps commanders and told them Lew Wallace’s and Nelson’s divisions were approaching. He ordered Prentiss in the center to hang on in the sunken lane “at all hazards” and personally helped somewhat to stabilize the still-retreating line. Parts of McClernand’s, Sherman’s, Prentiss’s, Hurlbut’s, and Brigadier General William H. L. Wallace’s units—the Union’s right and center—were taking a savage Confederate hammering but holding.

23The initial sight of a bloodied Sherman in the fray seems to have remained large in Grant’s mind. His own efficiency and coolness under fire in the Mexican War had led one combat associate to describe him as a man of fire, so at home where bullets flew that he seemed to belong there. Now he perceived in Sherman, so radically unlike him in many other ways, another man of fire. His battle report would go out of its way to praise Sherman. This favorable impression on his commander could only have been deepened by messages like one Sherman gave to a courier that day: “Tell Grant if he has any men to spare I can use them; if not, I will do the best I can. We are holding them pretty well just now—pretty well—but it’s hot as hell.”

24