Dragging for bodies near Caversham weir, Weekly Dispatch, 19 April 1896

Wednesday 8 April 1896

With one tiny body having already been recovered from the Thames and with an astonishing number of infants still to be accounted for, the police lost no time in overseeing the dragging of the wandering stretch of river which ran from the Clappers footbridge to the mouth of the River Kennet.

A number of local labourers were employed in this most gruesome of tasks. Henry Smithwaite was one such, and at around five thirty on the evening of Wednesday 8 April he brought up on the end of his hooks a parcel of what looked like linen rags. As the bundle broke through the surface of the water it split open and Smithwaite watched aghast as first a brick and then what looked like the shrivelled head of a tiny infant fell from inside the wrappings. The brick immediately sank from view, but the head, caught up in the current of the river, floated obscenely upon the surface before being whisked away and lost over the frothing waters of the weir.

The remains of the parcel were eventually recovered from the river and sent to the mortuary to be examined by Dr Maurice. The parcel consisted of a white linen wrapper tied together with cord. Wrapped up inside was the badly decomposed body of a male infant only a few weeks old. The infant was dressed in a chemise with a flannel band swathing its middle and two napkins fastened by a safety pin. Around the remains of his neck was a length of white tape, tied tight and buried deep in the flesh. As the body was in such an advanced state of decomposition, it was impossible for Dr Maurice to ascertain whether the child had been already dead when consigned to the depths of its cold grave. The jury at the inquest returned a verdict of “Found dead in the River Thames”.

The dragging operations continued. The unusual amount of activity on the river attracted the attentions of many curious passers-by who dallied by the towpath and voiced their theories in hushed and melodramatic whispers. By now rumours had spread and gossip was rife and the people of Reading were hearing, with horror, stories of missing children and of a woman being held at Reading Gaol who had used the river as a dumping ground for the murdered bodies of scores of innocent young victims.

Dragging for bodies near Caversham weir, Weekly Dispatch, 19 April 1896

At midday, a third body was hauled from the cold clutches of the water, wrapped in old sacking and tied up with thick cord. There was a brick in the parcel, tied tight to the chest of the nine-month-old baby boy curled up inside. There were two pieces of tape bound tightly around his neck and in his mouth was crammed a pocket handkerchief. What was left of the infant had been wrapped in an old white woollen shawl and a piece of twilled sheeting with patches on it. The baby looked as if it had been a fine one, with a crown of soft brown hair and enough teeth to enable Dr Maurice to establish its age.

The jury at the inquest held the next day was to return a verdict of “Found dead in the River Thames the presumable cause of death being suffocation”.

At about twenty to five in the afternoon, the team of draggers were to make their second macabre discovery of the day. Halfway across the Clappers footbridge at Caversham, on the left-hand side, a battered carpet bag with brown leather handles was caught on a hook and drawn up from the waters. It was tied around with string with about three inches left gaping open at the top and a piece of brown paper laid over the contents. Sergeant James, who had been superintending the dragging of this particular stretch of the river, cut the string from around the bag and prepared himself to examine inside. Although fairly certain of what he would find, he cannot have expected the pitiful reality of the sight that met his eyes. Wedged tightly into the bag, face down and one on top of the other, were the stiffened little bodies of two infants, one male, one female. There were also two bricks, a whole one and a broken one, both blackened by soot.

Up to Saturday five bodies have been taken from the Thames, all having met their death in a similar manner by strangulation with a piece of tape, the bodies then being placed in a parcel with a brick in it and deposited in the Thames. It is said that some thirty or forty infants were found drowned in the Thames within the London district last year, and that the bodies had been in the water six days or more, so that they must have been placed in the river some distance from London. Some of our London contemporaries hint at a gang of baby farmers, and that the Reading horrors are only a part of the doings of members of the gang.

Berkshire Chronicle, Saturday 18 April 1896

Saturday 11 April dawned warm and balmy. The bitterly cold days of late march had at last rolled away and spring had well and truly arrived. It was a day for throwing open windows and hanging stale bedding over sills to air; a day for pegging starched and dripping sheets out to dry and beating the dirt and dust from stuffy carpets. The residents of Reading would have hurried with their chores in order to join the throngs of people already gathered in the centre of Reading.

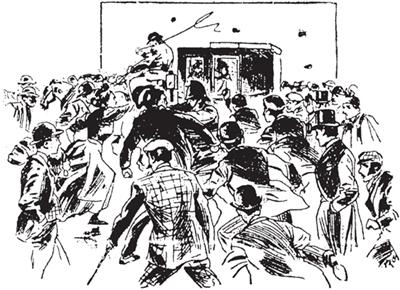

At an early hour the roads surrounding the courthouse were dense with onlookers, all anxious to catch a glimpse of the two prisoners due to appear before the magistrates. When a cab being driven at a brisk speed pulled up outside, its horses agitated by the noise and press of bodies, women, children, tradesmen and clerks all rushed forward, making it almost impossible for the occupants to step down. The crowd held its collective breath as a uniformed prison warder emerged from the dim interior of the cab, followed by a handcuffed Arthur ERNEST Palmer. The prisoner affected an appearance of lofty indifference as he was escorted down the cemented walkway into the entrance of the courthouse, the jeers of men and the screeches of angry women following at his heels. Dressed in silk top hat and long frock coat, he did not flinch at the indignation of the crowds.

The crowd mobbing Mrs Dyer, Weekly Dispatch, 3 may 1896

Before long another cab appeared in the distance being pursued by a mob of swift-footed boys. As it pulled up outside the courthouse the noise of the crowds abated to a murmur as the substantial figure of Amelia Dyer stepped heavily out on to the pavement. Accompanied by a female warder, she stumbled slowly and hesitantly down the walkway toward the doors of the courthouse, whereupon the crowds remembered their outrage and gave voice to it vociferously as she disappeared from view.

Arthur Palmer was the first to be ushered into the dock in the prickling silence of the courtroom. Carrying his silk hat under his arm, he looked the image of respectability, with perfectly trimmed whiskers and a dapper black and white checked tie contrasting with his colourless complexion. He stood poised and calm, watching for the doors to open and for his mother-in-law to enter the room. She appeared with a constable supporting her by the elbow and proceeded to walk with painfully slow steps toward her seat in the dock. Her face was devoid of emotion; her mouth set in grim determination. As she spotted Arthur standing waiting, she was heard to mutter to a court official, “What’s Arthur here for? He’s done nothing.”

Standing before the magistrates, Amelia Elizabeth Dyer was charged with “having on or about march 20th in the Parish of St Mary, Reading, feloniously killed and murdered a female child unknown”. Arthur ERNEST Palmer was charged with being an “accessory after the fact that he on march 30th did knowingly conceal the murder of a female child name unknown with intent to enable Dyer to elude the pursuit of justice”.

As the identity of the first body found was still in question, and as certain other matters had since come to the knowledge of the police, not least the discovery of more murdered infants, it was recommended that the case be adjourned to the following week.

![]()

Certain letters found in Kensington Road had led the police to contact Evelina Marmon, the barmaid from Cheltenham, and Amelia Sargeant, the married woman from Ealing, and on the morning of Saturday 11 April both women were brought from their homes to Reading.

Evelina had been informed by the police that she had placed her child in the custody of a woman who “could not be depended upon to properly act by it”; she left Cheltenham fully expecting to be able to bring her daughter home.

Instead she was escorted to a collection of grim buildings situated on Lock Island in Reading. Surrounded by the grey waters of the River Kennet, Lock Island was home to the Reading Corporation Isolation Hospital, and the mortuary. The cold stone room with bare brick walls and a sour smell contained the bodies of two dead babies lying on slabs with rough woollen blankets pulled up to their chins and with their heads resting on sheets of brown paper.

Evelina Marmon could not contain her grief upon recognizing one of the babies as her own Doris. It had been a mere eleven days since Evelina had given her child up into the care of a Mrs Harding. She did not at first understand the full implications of the horror that had taken place, exclaiming through her tears, “She was in perfect health when I sent her away.”

Amelia Sargeant was equally distressed upon recognizing the body of the second child as that of Harry Simmons, a child she had last seen only ten days earlier when she, too, had given him up into the care of a woman called Mrs Harding.

![]()

Until the mid-nineteenth century it was a requirement for Coroners’ Inquests not only to be held in public, but specifically in public houses. Southampton Street, Reading, was home to a number of such inns. Set a short distance away from the main hub of the town, the tall spire of St Giles Church towered over the street’s assorted buildings, casting its long shadow over the roofs of Lord Clyde’s Beerhouse, the Little Crown inn, and the Reindeer Inn with its advertisement for Hewett & Sons’ ales and stouts set solidly above dusty wooden doors. Across the street from the Reindeer Inn was a neat, well-maintained building with a polished glass-panelled frontage, bearing the name “St. Giles Coffee House”. Although it did on occasion provide its customers with steaming jugs of bitter coffee, it was in every respect an ordinary ale house.

On the evening of Saturday 11 April, within the cramped but comfortable confines of this particular public house, Mr William Weedon, local solicitor and acting coroner, held the inquests on the bodies of Doris Marmon and Harry Simmons.

Mrs Amelia Sargeant was the first witness called to give evidence. She was dressed entirely in black and was visibly distraught, having identified the body of Harry Simmons only a few hours earlier. She told the story of his short life and related the events which had led her to hand him over to a stranger at Paddington railway station. She had acted in good faith; she had been sure that “Mrs Harding” would be good to the boy.

“I have seen some of the clothing at the police station which I sent with the child. I made it all myself. I do not think the clothing has been worn since I sent it to her. My husband came with me when I handed the child to the prisoner at Paddington.”

Henry Smithwaite was next to give evidence and confirmed that he had found the carpet bag containing the bodies of the two children. DC Anderson and Sergeant James told how they had conveyed the bag to the police station, where, in the presence of Dr Maurice, the two bodies were taken out and photographed.

Young Willie Thornton proved to be a first-class witness. He gave his evidence in a “very intelligent manner” and earned the commendation of the coroner, who told him he was “the best witness he had had in a long time”. Willie proved that the carpet bag had belonged to him. He had brought it with him when he had come to live with Mother six months earlier. He knew the carpet bag was his by the pattern and the torn state of the inside. It was kept in a cupboard upstairs. The last time he had seen it was on the Tuesday before Good Friday. Mother had gone up to London and taken the bag with her.

Evelina Marmon confirmed that the body of the female child she had seen that morning at the mortuary was that of her daughter Doris. She was certain of the identity. She had had the baby vaccinated four days before she parted with her. She recounted how a Mrs Harding had come to Cheltenham to fetch the child. Evelina had handed over £10 and Harding had promised to provide Doris with a happy home.

“All for £10,” the coroner interjected, “an easy way of getting rid of a child. I don’t know how you could expect it to be done.”

“I wanted to pay her so much a week, but she said she wanted the child as her own, so that I could not fetch it away at any time.” Evelina sensed the coroner’s reproachful tone and added defensively, “I gave her a lot of clothes.”

The inquest was adjourned, pending further evidence, until the following week.