CHAPTER SIX

The House Where Death Lives

REVEALED:

How morticians became funeral directors, and Don Wilkerson’s Life in Death

In the waning days of the nineteenth century, the funeral home was a brand-new American business, as novel as the motion-picture camera, cotton candy, and the steel-framed skyscraper and as eager to establish itself to an inquisitive public. The undertaker had been around for a while, but the funeral director—who knew how to embalm and who took care of all the concerns one associated with funerals under one roof—was new. Pages from town directories from at least as early as the 1700s list the profession “Layer Out of Bodies.” It was a job often held by women who also worked as midwives. Until the very end of the 1800s, and even later in rural areas and much of the South, no one person took care of all the roles we associate with a funeral director. Instead, the operation was carried out piecemeal. Under the orders of physicians making home calls, families would first oversee the business of dying itself, from bleeding the sick to closing the eyes of the dead and tying the jaw shut with muslin.

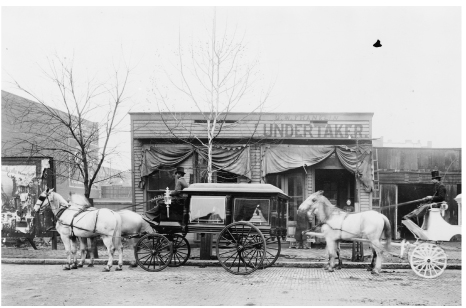

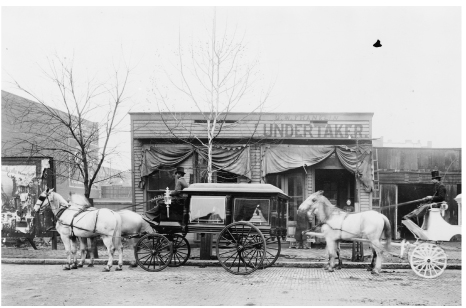

Horses and carriages in front of the funeral home of C. W. Franklin, undertaker, Chattanooga, Tennessee, 1899?

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, PRINTS AND PHOTOGRAPHS DIVISION, AFRICAN AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHS ASSEMBLED FOR 1900 PARIS EXPOSITION, LC-USZ62-109101 (B&W FILM COPY NEG.).

(Interestingly, bloodletting remained popular in the United States through the 1800s. Virginia Terpening, director of the Indiana Medical History Museum, tells me, “There was this idea that you could have too much blood, and that there might actually be bad blood. Problem was, they thought the body had a great deal more blood than there actually was.” As the practice declined, debate raged between those Civil War physicians who believed in bloodletting’s efficacy and those who did not. Phlebotomy is recommended as late as 1920 in at least one American medical text, which dictates that “To bleed at the very onset in robust, healthy individuals in whom disease sets in with great intensity and high fever is good practice.”1)

When someone in your household died, you might call upon your local carpenter. He made tables and shelves, so naturally he made coffins and put people in them, too. Or else he made a living selling or renting out carriages and horses, a universal occasion for such being, of course, the transport of the dead to graveyards.

By the late 1800s, however, a transition began to take hold. “If we know any good thing,” brags an announcement in The Casket magazine for the first annual meeting of the Funeral Directors of Michigan, “let us let our Brothers have the benefit of it and we will only feel better for it. The people at large expect more of us now than they did a few years ago. All they wanted of an undertaker then was to make or furnish them a coffin and they would have some friend or neighbor take charge of the funeral; but now it is far different. As soon as their dear one passes away they send for the Funeral Director, and they say to him, ‘We want you to take full charge and do what you think best.’”2

The display on one wall at the Museum of Funeral Customs is laugh-out-loud alarming. “The Long Motor pays him. It will pay you!” shouts the 1915 ad from Embalmers Weekly, in which a well-dressed, rather smug-looking man stands beside his hearse—which he also uses as a town ambulance. This particular duality of purpose went on in some places until the late 1970s, it turns out—around the time my mother had to call an ambulance when she was in labor with me. Finally, there’s an amateur photo here from around 1940 that pictures the long side of a black hearse with its door swung open. Inside, a young, white-capped nurse, her face a mask of efficiency, sits beside a reclining old woman who looks gray faced and disoriented. You want to make a joke about it, but it feels uncomfortable: Their port of call is not clear.

Today’s typical funeral business is a family business. It’s a profession built on trust, which is often based on reputations that run generations deep. In terms of square inches on glossy pamphlets and websites, the amount of marketing space that funeral homes dedicate to broadcasting their own integrity is considerable. This makes sense. When your father dies, the character of the people handling his physical remains and his memory matters to you. It also makes sense considering the storm of attack brought on by the publication in 1963 of Jessica Mitford’s book The American Way of Death. The work criticized the commercialized nature of the funeral trade; it also exposed financial deceit by businesses across the country. Funeral pros have spent the five decades since countering the public’s lingering distrust.

Actually, they’ve spent longer than that. Perhaps more than any other trade, funeral direction is built on a solid history of constantly reassuring the public. Take the new funeral directors at the turn of the twentieth century, whose job it was to convince the public for the first time that they were the ideal one-stop shop for getting the casket, calling the preacher, and getting the flowers, too.

Stephen George Wilkerson was among these enterprising young upstarts. A well-known county coroner, Stephen George saw the possibility of major success in the new business of death. It was 1932, and like many rural and southern places across the nation, his town of Greenville, North Carolina, was only just starting to move away from the tradition of the home funeral. Greenville was a small town—the population in 1930 was just under ninety-two hundred—but it was growing year by year into the square miles of cotton fields surrounding it. Upon establishing S. G. Wilkerson and Sons, Stephen George faced a diverse set of unprecedented challenges: determining the number and style of caskets to order and from which manufacturer, figuring out the best way to approach the grief of a set of young parents, and determining how to earn and maintain a good name for himself in the community so that an entire population might trust him to manage completely these raw, difficult, and socially important moments in their lives.

Splashy trade publications like The Casket and Sunnyside—which later converged into one magazine—helped young Stephen George make these decisions. The tabloid-sized pages gave voice to the ambitious mood of the funeral trade in its early days in vivid print and illustration. Fiery opinion pieces competed for space with eye-catching ads for hearses and caskets and embalming fluids. The ads made bombastic claims or masqueraded as articles. Behind it all pulsed the drumbeat of progress and modernity. For example, a letter to the editor in a March 1898 Casket decries the “old fogy ways that still cling to” a good number of Kentucky undertakers who had refused to learn embalming or to sell manufactured caskets—insisting instead on the “deficient” homemade variety.3 The editorial line was a bit hazy in this publication containing all sorts of ads for the latest manufactured caskets, vaults, and so forth.

The pages were rife with brand-new inventions. Another issue from the same year contains an ad for a patented metal chin supporter—to keep a dead jaw from dropping open in the middle of a viewing—and a number of competing burglarproof vaults. And then there’s the patent notice from an Ohio man in the July 1880 Casket for the “Coffin Torpedo,” which would fire a missile at any would-be grave-robbers. As a safeguard, the torpedo included a “rod [that] extend[ed] to the surface of the ground[,] to prevent any accident when filling the grave.”4 How exactly this safety rod would prevent the torpedo from wounding innocent gravediggers is not explained. Perhaps the weirdest ad, though, is a half-pager that features a photograph of what first appear to be a couple of scarecrows. Upon a closer look, you realize that they’re two exhumed corpses, apparently a woman and child, all desiccated and sticklike. G. H. Hamrick’s Embalming Liquid is the responsible party. The ad’s copy brags that the bodies were infused with his magical potion ten years prior. Says the proud underlined copy: “You can make mummies with it.”

Trade magazines also boasted professional how-to stories like Joel E. Crandall’s 1912 breakthrough feature in The Sunnyside, in which he submitted a brash new concept called “demisurgery” (later renamed “cosmetization”). Before, the primary aim of embalming had been to harden the body to a rocklike texture in order to preserve it as long as possible, á la G. H. Hamrick’s mummy-making potion. But Crandall proposed that embalmers might consider a different goal: through the use of makeup and other materials, he wrote, he had found a way to erase the physical evidence of a violent death, so that family and friends might “look upon their loved one again” before burial.5 It sounds very much like the Victorian ideal of the Good Death. However, later critics—people like Jessica Mitford and advocates of green burial—are harsher in their assessment. To them, “cosmetizing” a body means the funeral industry’s attempt to erase real death from our experience of it.

Funeral directors don’t see it that way.

Deep tradition matters and so does progress, and if there’s anyone in Greenville, North Carolina, who’s aware of this, it’s Stephen George’s grandson, third-generation funeral director Don Wilkerson. This is how Don gives you the facts about progress: “It seems that Greenville might be the center, in eastern North Carolina, as far as health care goes.” His tone is polite, his word choice indirect, but what he’s saying is accurate. Greenville today is home to Pitt County Memorial, the teaching hospital for East Carolina University’s Brody School of Medicine. The town also boasts one of North Carolina’s fastest-growing public universities, one of its largest convention centers, and plans for that pinnacle of any real American metropolis: an ovoid beltline reaching some twelve miles’ diameter at its widest north–south span. Greenville is one of the fastest-growing towns in North Carolina. It’s just up the road from Wilmington, where I live, and also near the tiny burg where my mother grew up.

The carloads of newcomers to Greenville from other parts of the country might judge Don Wilkerson’s above statement as indirect. What it really is, however, is prudent. In telling me what she knew about S. G. Wilkerson and Sons, a woman in her seventies who had lived in a neighboring town all her life used a similar style of explanation. “It’s the—well, everybody knows about Wilkerson’s, of course, it’s the big, well, around here, in terms of funerals and cremations.”

For the physical structure, big is a good word to describe S. G. Wilkerson and Sons Funeral Home: The two-story brick structure takes up an entire tree-lined block just off Greenville’s main commercial drag. Wilkerson’s dwarfs the United Methodist church next door and in fact looks a lot like a church itself, all beige-brick modern, that style so popular for ecclesiastical architecture in the 1970s and ’80s. A magnificent stained-glass sanctuary dominates, and when early in our conversation I ask Don whether their building used to be a church, he says, not unkindly but with a hint of frustration, “No, no. We had this building built in 1975.” I’m reminded of another church-that-isn’t, the Museum of Funeral Customs in Illinois, a structure that similarly reads spiritual without actually cleaving to any particular faith. The tone of Don’s comment doesn’t miss its mark, either. Someone who had lived here in 1975 would have known that this had never been a church.

Don’s entire thesis in our conversation today has to do with insiders—the people who grew up in and around Greenville and the small farming communities surrounding it—and outsiders, those who have arrived in recent decades, from other places. As these newcomers arrived, life changed in and around Greenville—and death, too. The decades have altered, in ways surprising and fundamental, the manner in which funeral operators like Don work and, as it turns out, the very meaning of what they do.

After observing the business the whole of his early life, Don started working here summers at age seventeen. After graduating from college at twenty-four, he returned to work full-time as a funeral director. At that time, the early 1960s, Wilkerson’s saw most payments at one time of year only. “A lot of our accounts receivable were what they call fall accounts. You carried the account until fall because that’s when tobacco was sold and that’s when the bills were paid. Banks were the same way.” At that time, a skeletal sequence of Main Streets broke up the region’s flat expanse of farmland and scrub swamp. These were the little towns of Greenville and Kinston, and around them the humbler settlements of Ayden, Grifton, Winter-ville, and Hookerton. They were all linked by Highway 11’s two lanes and stamped with miles of tobacco and cotton fields.

All that flat farmland proved a defenseless canvas for the fleet of car dealerships, fast-food joints, and shopping malls that began their unremitting march out from Greenville four and a half decades ago, when East Carolina College became East Carolina University and, soon after, the hospital began its massive expansion. Pharmaceutical research giant Burroughs Wellcome arrived in the area around the same time, as well as a number of manufacturing plants, including Dupont. In 1950, the population of Greenville and the areas surrounding it was just over sixteen thousand. At the time of my conversation with Don Wilkerson, it tops seventy-two thousand.

Such a populace makes the traffic on the town’s main commercial drag a sight to behold the Friday after Thanksgiving. The malls surge like anthills with shoppers who swarm the parking lots of Panera and Applebee’s and Starbucks, their Escalades and Rangers stacking up by the dozens at each traffic intersection. Around the corner and inside the hushed carpeted hallways of Wilkerson and Sons, business is the same as it is year-round. Today, four services will take place or have already taken place—two graveside, and two more in-house. As Don sits across from me in a small conference room dominated by a table of dark wood polished to a mirror-ball shine, there are at least three other conversations taking place in similar rooms around the building. In those rooms, at those tables, visitors are planning funerals, their own or those of parents, spouses, or children they’ve just lost. Don Wilkerson plays the straight man for such emotionally loaded conversations every day he works, discussing with people which flowers, Bible passages, music, and caskets define perfectly the lives of their fathers, great-aunts, or selves. He addresses larger questions, too. Am I doing this right? Why did this happen? What’s next?

Don is semiretired now and works just three days a week rather than the seven days, thirteen hours per, that he put in for forty-some years. (S. G. Wilkerson and Sons does business roughly 364 days a year, closing to visitation on Christmas Eve and Christmas morning only.)

Today his dress is characteristically prim: neat silver-frame glasses and a black suit, a bright Carolina blue tie adding a spark of conviviality. The tie is like the small jokes he starts to venture about thirty minutes into our conversation. (The first, to drive home the point that death could come at any time, for any of us: “Heck, a jealous husband could shoot me!” an infectious chortle pealing out quickly before he adds, “I don’t know what he’d shoot me for.”) When he laughs like this it’s surprising, as there is so much about this man that telegraphs strict propriety. However, Don Wilkerson is also a good old boy, and I mean the term in a positive sense, the way my own male relatives from this part of the country use it: as in hail-fellow-well-met. “Oh, Don? He’s a good old boy.”

However, Don also moves in and out of these frank discussions about death smoothly, unlike a single one of those male relatives. He himself has had his own brush with mortality—a heart attack in his early forties. He has claimed a born-again health-club fanaticism ever since. (He blames the heart attack on the long hours; he does not, overtly, blame the breakup of his first marriage on the same, although it took place at roughly the same time, both in his life and in a five-minute span of our conversation.)

Counting funerals, cremations, and bodies shipped to other states, Wilkerson and Sons oversees about 650 cases a year, a strong number for a major funeral home in a growing metropolitan area this size. When the firm started in 1932, it was a small funeral home in a small town. By the 1970s, it had an on-site crematory, which was by then a common practice for elite firms around the nation. Wilkerson’s also owns and runs Pinewood Memorial Park, a well-ordered ninety-five-acre cemetery near the university. In the 1950s, when the Wilker-sons purchased Pinewood, cemetery ownership was a hallmark of extremely successful funeral operations. However, times have changed, and Don frowns when he brings the place up. Perpetual care is the predicament. “Problem with cemeteries,” he says, his thick brown eyebrows knitting themselves together, “whoever owns it has got to maintain it. And it’s a constant maintenance thing. That’s a reason churches got out of cemeteries first. Then families got out of the cemetery business by selling the land.”

Wilkerson and Sons is still in the cemetery trade, even though every year more and more people are opting for cremation, and more and more, those ashes are not buried in cemeteries. And then there’s the upkeep: mowing and weeding and monument preservation, which gets to be expensive for an independent business, especially when you consider the fact that cemeteries in this country are not the popular draw they once were for visitors. It’s hardly the mall on a Friday after Thanksgiving. It’s hardly even the softly lit halls of a successful funeral home on any day of the week. Once, the Sunday afternoon gravesite visit was customary for people in communities like this. But times have changed.

Two centuries ago, I would have called Don Wilkerson a funeral undertaker; a half-century later, just plain undertaker. The term “funeral director” wasn’t invented until the late 1800s. Up until around the Civil War, people specified a “funeral undertaker” when they meant someone who dealt with the dead. The world saw the dramatic birth of term “mortician” in a February 1895 issue of Embalmers’ Monthly: “In the January … Embalmers’ Monthly[,] the wish was expressed that a word might be coined that would take the place of ‘funeral director’ and ‘undertaker.’ … We have given the subject considerable thought and … present the word ‘mortician.’”6

A business like the death trade is going to involve some euphemisms. These will change every few generations or so, as the old euphemisms lose their euphemistic quality—that is, their power to make people conceive of death as something less than the scariest thing imaginable. There was the coffin-to-casket switch. The funeral chapel–to–funeral parlor–to–funeral home–to–funeral service switch. And the graveyard–to–cemetery–to–memorial park switch.

“Mortician” might be a riff on the reputable, medical “physician.” Given the funeral trade’s extremely fragmentary record, there’s no way to know for sure. But over time, anything related to the dismal trade, including “mortician,” takes on grim connotations. Really, there’s not a whole lot more uniformity today in the professional labels of those who work with the dead for a living. “Undertaker,” “funeral director,” and “embalmer” tend to be used interchangeably in current embalming textbooks and trade magazines. Despite the ingenuity of the minds at Embalmers’ Monthly back in 1895, the term “mortician” failed to triumph over all, which is good, because the publication got to keep its name. However, these days, most professionals advertising themselves these days do so as “funeral directors” rather than as “morticians.” Who knows why this is. Maybe it’s that pesky Latin “mort-” that calls to mind, again and again, the fact that this person works with dead bodies. Then again, that’s most likely my own bias revealing itself: The comprehensive funeral director of my imagination runs the whole show, leading widows to caskets and securing flower arrangements, while the pasty, bent mortician sticks to the shadows of the cold embalming table.

As for the humble “mortuary” from whence “mortician” sprang, it’s really the granddaddy of every one of these terms, having been on the scene for hundreds of years. At one point or another, “mortuary” has meant just about everything we have ever associated with death and memorialization. It holds a two-hundred-year stint as a synonym for “funeral” in the fifteenth through seventeenth centuries. This overlaps with its definition, through the nineteenth century, as a special tax paid to the church when someone died. In the seventeenth century, “mortuary” is also another word for a burial place, and it makes at least one appearance as an eighteenth-century synonym for a written remembrance—a precursor to the modern obituary. Its modern definition, “a building or room for the temporary storage of dead bodies, either for purposes of identification or examination, or pending burial or cremation,” first appeared in an 1865 trade publication. As part of the effort to establish the funeral business as an authentic, even—again—medical, industry, Casket and Sunnyside magazine in 1936 introduced the term “mortuary science” to refer to “the theory and practice of embalming and funeral directing as a subject of academic study.”

When undertakers became funeral directors and began trumpeting their very own patented products in their very own trade magazines, it was only a matter of time until home funerals died and funeral homes were born. But there were other forces at work, too. The Civil War played a huge part in moving death out of the house, an emigration that felt extremely unnatural to Good Death–loving Americans who were used to caring for their dying and dead there. Some of the first modern undertakers were entrepreneurs who hung their shingles on barns near fresh battlefields, offering to locate bodies, embalm them, and ship them home. Virginia’s Dr. William MacClure advertised that “‘bodies of the dead would be ‘Disinterred, Disinfected, and sent home’ from ‘any place within the Confederacy,’” and he had his share of Yankee counterparts as well.7

The late 1800s was also a period when the sick and mentally ill left homes and went to the new hospitals. As the new century arrived, death took place less frequently at home—and less frequently, period, as a result of advances in medicine and sanitation. It became something that people experienced more and more often alone, and it was handled now by specialists and strangers—physicians and nurses—at places that did not resemble the home.

The moment was right for funeral directors to create a physical space of their own. The new “funeral chapel” came first. Funeral directors often ran their businesses from mansions previously owned by upper-crust families. The large houses offered social prominence, expansive living areas upstairs for the directors’ families, and large basements that were ideal for embalming.

Issues of The Casket were peppered with glowing profiles during this time that served as how-to prototypes for aspiring young mortuary owners. A 1905 article trumpets the Frank C. Reavy Estate, in Cohoes, New York, as “a Model of Completeness and Up-to-Dateness.”8

Readers are filled in on the business’s every praiseworthy particular. There are “handsome cabinets” finished in white enamel “with mirror-inset doors, the interior measuring 8 × 13 feet, and lined with black velvet,” which display funereal robes for the deceased. Such fine detail, claims the story, regularly prompts the residents of Cohoes to “make it a show place to their visitors.” I love this idea: We’ll round out the evening taking in a play, but first, to the mortuary!

Moreover, what young mortician wouldn’t read this piece and dream of his own such business, complete with an “attractive” exterior “finished in paneled oak, large panes of glass, with … opalescent borers, and no display of gruesome objects”? These magazines are filled with such profiles, each, as one publication put it, serving as “an example that may well be followed by others who contemplate the erection of a real ‘Funeral Home.’”9

That set of quotation marks around “funeral home” belongs to Embalmer’s Monthly, not to me, as the term was still tentative in 1915. The funeral chapel came first, and then for a while businesses were called funeral parlors, a name coming from the room in family homes where people had traditionally met with company and laid out their dead.

But then around World War I, about the time the British were tossing their widows’ weeds in the name of God and country, parlors began disappearing from homes. Homemaking magazines decried gloomy “parlors,” now linked inescapably in people’s minds with death before the advent of modern medicine, favoring instead a new kind of space and title: the living room. Funeral operators themselves followed suit, to avoid appearing Victorian and outdated. Their businesses became “funeral homes.” In later decades, when many funeral operators abandoned the old mansions for stand-alone businesses, they abandoned the term “home,” too, in favor of the ever more distant, professional “funeral service.” Yet most of us still think of them as funeral homes, those places where death lives.

In Greenville, Wilkerson’s has been that place for decades. Back in the 1940s, Don Wilkerson’s father and uncles guided the company. In the casket storage room, they would advise you on what to buy and then take a legal pad and lean it up against one of the empty caskets, all stored upright in those days, to figure your bill before shaking your hand on it. When fall came, they’d walk the invoice over to your house or place of business, where you’d sit and talk awhile. This last practice was started by the elder Wilkersons and continued into the 1970s. All these men were affable men, and all respected countywide, just like Stephen George, who founded the firm in 1932. In the early twenty-first century, we are not untouched by these facts; their contours remain. On the webpage labeled “Staff” on the Wilkerson Funeral Home website, founder Stephen George was listed first, his four sons next. “Deceased” read the bold font above their names. This is why Don tells these stories. To make the listener understand: We are here. We are sunk down deep; the deeper we sink, and further from this moment, the more entrenched we become in the here and now.

You can guess the percentage of cremations a community might have from the education level of its citizens. “Usually, university settings will lead the way,” says Don. Here in East Carolina Pirate country, the number is about 27 percent—roughly 13 points below the national average for cremations, which hovers now around 40 percent. Over in the central part of the state, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, founded in 1789, has arguably played a strong role in its community for much longer. There, the percentage of cremations is far higher, around 42 percent. These numbers both eclipse what you’ll find in some other North Carolina counties—like rural Hertford County, due north of Pitt County on the Virginia State line, population twenty-four thousand. Hertford’s cremation rate is 11 percent.

If you were to look up the term “progress” in the dictionary, you’d find something about advancement or development toward a better, more complete, or more modern condition. Look closely. There are two definitions housed in one: the “better, more complete” and the “more modern.” In Don Wilkerson’s personal view, the progress inherent in the growing popularity of cremation has everything to do with the latter but less to do with the former.

Wilkerson’s houses the county’s only on-site crematory, and it does a swift business. The display room features an attractive array of urns: boxes crafted of finished pecan and cherry wood, many adorned with artistic bucolic scenes—enough flowers and trees to chart some new forest, a place called Expiry Woods, maybe, which is probably the name of a real-life cemetery somewhere, some place with real trees and real flowers. In this room, I absently play the mental game of “Which might I choose if … ?” and settle on a simple box that looks like walnut or locust wood, burned with the striking silhouettes of a few birds—gulls?—taking flight. There are still more to choose from: delicate vases and sterling silver boxes. And Don points out a papier-mâché plate onto which ashes are meant to be sprinkled. The plate comes with a lid decorated in watercolor with pink and yellow flowers. One floats this ultimate picnic set out onto a body of water, and the lid prevents a windy day from ruining the farewell. At the moment of good-bye, the set will float out, placid and dependable, and then sink and biodegrade, guaranteeing that your father really rests in the deep of the Cape Fear River and not around the pilings of the dock you’re standing on or, worse, in the folds of your own jacket.

Wilkerson and Sons makes these cremation products available, but they’ve placed them in a separate side room from the central casket display gallery, which holds main event status with its even more myriad personalized options. The blue-ribbon casket here is crafted of bronze, offering “the very finest in materials, workmanship, permanence and durability,” according to Wilkerson’s website. Other models are crafted from copper, stainless steel, plain steel, mahogany, walnut, hickory, birch, cherry, maple, oak, poplar, or pine. Wilkerson’s carries two popular brands of caskets. One of these, Bates-ville, offers the option of the MemorySafe® drawer, where keepsakes and farewell messages can be displayed and stored forever. Personalized designs on casket panels are another option. Then there are the optional LifeSymbols®, models sculpted from acrylic that fit into the alcoves of casket corners. Think mini golf clubs, praying hands, gardening tools, even a lighthouse for the deceased seafarer.

The idea of having a picturesque death scene replete with items like elaborate caskets dates back to Victorian England and the Good Death. However, while such pomp was quashed in the United Kingdom in part by that nation’s massive casualties during the First World War, funereal finery in the United States continued to flourish even as our own attitudes toward death changed.

In this country, even when prescribed mourning periods and weeping veils went away, the physical Beautiful Death lived on in funeral homes—and at home funerals, too. Into the 1930s, ’40s, and even ’50s, funerals continued to take place at home in many small towns and rural places around the country, and great importance was placed on the appearance of such events. The caskets here at Wilkerson’s remind me of an exhibit I saw at the Museum of Funeral Customs displaying a typical home funeral from the 1930s. A wooden casket lined in candy-purple plush presided before a darker purple backdrop. This casket loomed, draped in a mile of sparkly white bunting, all of it seeming to float, dreamlike, above vases bursting with fake white and purple flowers, a veritable floral sea. The effect was dramatic. It made me stop and catch my breath. It was kind of a beautiful death, lacking only, at that moment, the death. For years and years, it was the job of the undertaker to create such a visual effect in people’s front parlors. Funeral workers of the day, people like Don Wilkerson’s forebears, brought to people’s houses all the ingredients for a presentable service, like traveling carnival workers. Or like salesmen: The dark purple backdrop on this exhibit folded open from a suitcase to stand behind the casket for the viewing, like those old briefcases that popped open to transform into displays of fine cutlery. In the early days of the twentieth century, every single such item—from the six-foot, aubergine velour curtain with its folding metal stand, to the small clip lamp that illuminated the deceased’s face—would have been brought to the house of the deceased by the funeral professional.

This period had its own stylish trends, 1930s versions of the acrylic golf-ball panels. The open upper half of the museum casket was covered with a glass sealer, a fashionable preservative measure—basically, a small, round window through which visitors could view the deceased. According to the display text, the sealer “softened the visual image of a viewing, discouraged individuals from touching the body and kept insects away from the deceased when windows needed to stay open in the days before air conditioning.” Its crafters had good sense, considering occasional hot days that harbored the twin threats of insects and melty cosmetics—even though the little round window with its bolted, metal rim made the casket look a touch Jules Verne to me.

Still, then as now, there was an incredibly pleasing design element to it all, which made me think of one responsibility of funeral professionals that I’d never really considered. Once funeral directors took on the job of creating the entire service, they also took on the job of creating the presentable postmortem scene. The embalming, the lighting, everything had to be just so, even the casket itself, resting at an eye level ideal for viewing. And for all this, we have those Victorians to thank. Without that prototypical home deathbed scene of heavenly homecoming before a loving family audience, there would have been no purple-plush-lined casket, no personalized casket panels of praying hands clasped together for eternity.

An even better modern counterpart to the Twenty Thousand Leagues glass sealer is the Cadillac of vaults. Most cemeteries require vaults, those concrete or metal boxes that enclose caskets and cremation urns once they’re in the ground. Although vaults were originally invented to fend off Victorian grave robbers, cemeteries today require them because they keep the earth from settling into the grave. There are several vaults on view here at Wilkerson’s, though it’s nothing compared to the multiplicity of vaults displayed on the funeral home’s patiently detailed website, where I count no fewer than fourteen different varieties, everything from the triple-reinforced Wilbert Bronze to the lowly Continental concrete model.

Don takes pride in showing me their very finest specimen here in the big display room. In the spot where your eyes first naturally rest sits a dome-topped model fashioned completely of galvanized steel. “It’s an air-sealed product,” says Don, tapping the shining chamber with pride. This vault resembles a giant silver bullet; it looks missilelike in its sturdiness. If the vault were any larger, it would resemble the bunker where I’d want to be in case of nuclear apocalypse—although I’d have to bring an oxygen tank, since it’s designed not to let anything in, especially not the two enemies of preservation: water and oxygen. “And that casket, once it’s in that vault, is in the air,” Don says, gesturing again with his whole hand for emphasis. “There’s not room for anything to get in there. It’s tested at the factory in six feet of water, and warrantied against the intrusion of water. Most funeral homes, you’ll find, don’t have the capacity to inventory and to install it.”

I’m left thinking of the technical raison d’être we often hear for vaults, to keep cemeteries looking golf-course beautiful, and this other reason that dominates Don’s sales pitch. Body preservation. We don’t have dust to dust here. We have, in some cases, dust to mummy. It is true that funeral homes make the bulk of their income from casket sales, and if you buy a casket, you pretty much have to buy a vault. Hear those cash registers.

Sort of.

Because there is more at work here than profit motive.

In the urn room, dwarfing the small funerary boxes with their flowers and trees, an actual cremation container leans against the wall. It’s exactly like a coffin-shaped office storage box, made of white cardboard, specially treated. (“It must be able to contain bodily fluids,” says Don.) Across the lid, in green sans-serif print, the words “Name,” “Date of Death,” “Gender,” and “Age at Death” stand out in bland, blameless, horrifying veracity. Several finer cremation caskets made of wood repose in more traditional positions here as well, but something about the severity of this upended model says, Interested in cremation? This is what it comes down to. This, in the end, is what it’s all about.

There’s something at work in these layers of history upon which we sit here in Greenville, North Carolina. Don says nothing outright that can be construed as a personal opinion about the practice of cremation. What he does say, though, is telling. “On our side, in funeral service, there’s always been a couple of things that went on.” He places the tips of his fingers together as he speaks. We are back in the privacy of the conference room. As he glances up to find his words, the overhead fluorescents dazzle his glasses for a moment, and I can’t see his eyes. “One, maybe if you don’t look at the death, maybe it didn’t happen,” he says. “Have you ever heard anyone say, ‘I can’t believe that Joan is dead’? Well, maybe they didn’t go to the funeral, but seeing is believing. The body in a casket. That’s how infantile, sometimes, we are. People naturally shy away from it. It’s ‘Oh, I don’t wanna see that.’”

But maybe they should. He never says this, but the words hang in the air, as legible as though he’d taken an indelible marker and written them on a pane of glass between us—and before we get to Don’s anecdote about this, I’m going to interrupt with one of my own.

In The Puritan Way of Death, David Stannard describes the harsh conditions of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century New England, a time and place in which, besides accusing one another of witchcraft, the nation’s earliest and cheeriest settlers also saw fit to pass the time warning their children about their likely imminent demise and hell. Constantly. In the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, dying was no shrouded surprise to anyone; even later, by 1850, some twenty-two to thirty-four of every one hundred infants did not reach a first birthday. It was truth in advertising when children were advised, in sermons like one by Cotton Mather, to “Go into Burying-Place, children; you will there see Graves as short as your selves. Yea, you may be at Play one Hour; Dead, Dead the next.”10 Fun fact: Mather spoke this sermon at a child’s funeral—that of fourteen-year-old Richard Hobby, who was “crush’d to death by a cart falling on him,” according to a diary account.11

Puritan advisement on death commonly had to do with what children—and all Puritans—would find on the other side. One famous (or infamous) children’s sermon by minister Jonathan Edwards described the spectacle on the infernal side of the veil this way: “How dreadful it will be to be all together in misery. Then you wont play together any more but will be damned together, will cry out with weeping and wailing and gnashing of teeth together.”12

Such admonitions weren’t meant simply to keep children in line; Puritans believed in Predestination, which meant that they had no control over their ultimate fate. Everyone feared eternal damnation.

By the start of the nineteenth century, the outlook had changed. Parents still talked to their kids about death and children still witnessed an awful lot of it, but in the new optimistic evangelical era, the faithful were guaranteed a place in paradise. In short: If you believed, you were heaven bound. Now, at least publicly, death became a glorious, even eagerly anticipated state. It meant reunion with lost loved ones rather than eternal separation. The Good Death was born. Stannard writes, “It was becoming the … accepted norm, for the godly to die ‘in Raptures of holy Joy: They wish, and even long for Death, for the sake of that happy state it will carry them into.’”13

So what does death “mean” today? In this pluralistic society, it depends on whom you ask. Recent surveys suggest that most Americans believe they’re going to heaven after they die. At the same time, fewer and fewer of us are reporting an affiliation with any organized religion. There is no single prevailing societal take, and individual, non-faith-based analyses frequently tend toward the foggy. With child mortality as low as it is, there seems little point in scaring small children or ourselves by ruminating on something that we are all so sure, in the backs of our minds, happens only to old people, a group becoming, with the elevation of medical and living standards, less and less Us. Stannard writes that more often than not, death is never really addressed to children—or to the rest of us—as a real event at all. I’m talking about not the deaths of movie villains, but yours and mine.

Stannard goes on to condemn this way of thinking. We’ve become a society that avoids and denies the existence of death, he says. Hence, the sterile, inhospitable hospitals in which so many people die.14 He has a point. Think of the often lonely conditions of our euphemistically termed “rest” homes, or the sanitized portrayals of violent events by U.S. news: American television coverage of the Iraq War or of any other conflict compared with that of, say, European networks. For U.S. viewers, the human face of real death always manages to take place off camera.

Compared to the Victorian era’s prescribed black mourning period and dress, grieving today is somewhat abbreviated. In his essay “The Reversal of Death,” French scholar Phillippe Ariès describes a “mourning curve,” or arc of emotionality through the decades in our attitude toward death. He describes the nineteenth century as “a period of impassioned self-indulgent grief, dramatic demonstration and funereal mythology”; now, he says, we are experiencing a trough. Even in our closest friends and loved ones, we brook very little “dramatic demonstration.” Instead, we expect expressions of grief to take place in private.

Blame it on etiquette queen Lillian Eichler and her ilk of yesteryear; grieving today is nothing compared to what it was in the 1800s. Then again, we may no longer be dwelling in quite the “trough” we were in when Stannard and Aries penned their complaints in the 1970s. After all, Don Wilkerson’s town of Greenville, North Carolina, is home to at least two hospice-care facilities—places that champion the opposite of emotional avoidance of the Grim Reaper. Many such places encourage the living to pay their respects both to those on death’s door and to those who have just walked through it. By championing comfortable dying in people’s homes or in homelike settings, in fact, hospice might be the new Good Death. The National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization reports that in 2011, hospice care shepherded about 44 percent of all U.S. deaths.

Then again, other evidence suggests that maybe we’re avoiding death more than ever. The rate of direct cremation—that’s cremation with no service and no viewing—has risen even further since the days of Stannard and Aries, as have memorial services without the body, “to which,” as poet and undertaker Thomas Lynch derisively wrote, “everyone but the dead guy gets invited.”15

If anyone’s uncomfortable with seeing real death here today, it’s me. Visiting the urn room, but especially the casket room, jars me (“casket” being just a euphemism after all for “coffin,” and it’s not so very far from the unnerving visual of coffin to that of bodies and thoughts of one’s own and the impossibility of Null and Never, and the memory: those childhood middle-of-the-night death panics and my father’s attempts at comfort, hands stroking shoulders as if to verify our presence at that moment, his and mine, always with the final refrain, “Not for a long, long time”). It is what makes me feel strange even talking to a funeral director, realizing every two minutes the things he sees every single day.

I’ll just say it, though it unnerves me to do so: As I write this, I am a death virgin. (Knock mahogany, walnut, hickory, birch, cherry, maple, oak, poplar, and pine.) My father lost his younger brother when he was a child, and he doesn’t like to discuss it, nor does he harbor an ounce of interest in cemeteries, funerals, or my current preoccupation with both. Then again, I have a friend whose father died a few months ago. He brings the subject up frequently, analyzing it from all angles, and every time we talk, he presses me for any new details I’ve dredged up in this particular death trip of mine. He can’t get enough. I have friends who find cremation—those flames, that conveyor belt—horrifying. I have other friends who shudder at the thought of whole-body burial in the ground.

You can only understand how someone else needs to handle death in the given, specific moment. There are few hard and fast rules. I understand both my father and my friend. Or rather, I understand neither and so allow both the dispensation the ignorant should grant the wise. The postulate that we have become alienated from death can be argued in the abstract, with timelines and wholesale societal evidence. And maybe on the whole it’s true. However, even after analyzing our own conventions, we are to some extent stuck inside them, as I am stuck to today’s popular view when talking to my father and my friend: that no matter who you are, you cannot tell someone how to do death.

Not like you used to. Don tells this story.

In 1972, they were demolishing the old bridge that links Content-nea Creek to Highway 11, over in Grifton, to build a sturdier one. I perk up and nod when he says this. I know this bridge. I cross it every time I go to my grandma’s.

“And this guy was from Aurora,” says Don. “Somehow, he got killed in the bridge demolition.” It’s something of a jolt, from the familiarity of the bridge over that swamp-kneed creek of my childhood, to death. Somehow I keep forgetting that over the course of this conversation with Don, a given anecdote will always lead to the main character facing a freak accident, a heart attack, or an ocean drowning.

Don continues: “These people, they were not churched. She wasn’t from Aurora. This gal was about, I don’t know, twenty-eight. Anyway.” Anyway, this gal, who remains “this gal” for the remainder of the tale, went to a funeral home in nearby Kinston. She told the director there that she wanted to have her husband cremated. The director refused, and then he lectured her on why cremation is neither proper nor smart. Don nods as he says this, like this is a conventional course of action, to tell a potential customer, No. You’re wrong. That’s not how it’s done, and you’ll regret this move. At the time, it was.

Well, he tells me, this gal sat there and listened to the funeral director’s advice and then stood up politely and left. She called a Methodist minister in town who then called Don and said he didn’t know this gal from Eve, nor did he know what to do. So S. G. Wilkerson and Sons arranged for the cremation. There’s more: When Don told this gal to bring in a nice suit of her husband’s for his actual cremation, she refused, since the crematory flames would destroy the suit and anyway it was not like she would even be present. That’s where Don himself drew the line. “And I said, ‘Now, listen. There’s a right way and a wrong way.’” In the end, she brought him the suit. Then, just before the cremation, she decided that she wanted to see her husband’s body for a moment after all. “Seeing the body meant something to her. She didn’t think that before.”

This anecdote is a layered one, with multiple theses: First, Don’s saying that in order to grieve properly, we need to see our loved one dead, to connect the vacant body with true absence. His subtle opposition to cremation goes deeper than base salesmanship; he believes in the traditional funeral as a rite that has meaning to people in grief. Then there’s his second point: This is the brand of disarray you’ll see in a woman without a church, a people. This is related to point number three: This is what our world has come to. It’s a world in which families aren’t “churched,” and a world in which women no longer value dressing their dead husbands well to send them off properly from this world.

Finally, it’s a world in which the funeral director no longer has final authority. The story marks a turning point in Don’s life, an occasion when he served as arbiter of both propriety and desire. For most of the twentieth century, a funeral director’s responsibility was defining the proper course of action for people locked in their deepest stages of grief and helplessness. Now, his role is to appease the desires of such families, no matter what those desires might be and no matter his personal feelings. The funeral director is no longer a social institution. Like so many other things, the position has become, instead, a consumer resource. Hence the paper plates for cremated remains, and hence the crematory itself, which, unlike the cemetery, comprises a greater percentage of Wilkerson and Sons’ earnings each year.

And this is Greenville, North Carolina, a town seated like so many across this country, at the crossroads of old and new. It is a place of contradiction, absolutely an up-and-coming center for health care and manufacturing, but also a fairly small rural town where family roots run deep. An informal Internet search also turns up two mosques, one Jewish congregation, one Hindu congregation, and ninety churches in Greenville proper. There’s Baptist, Assembly of God, Christian, Church of Christ, Church of God, Free Will Baptist, Methodist, Pentecostal Holiness, Presbyterian, Reformed Evangelical, nondenominational, and a smattering of Wesleyan, Seventh-Day Adventist, Lutheran, Episcopal, and Catholic congregations. In the small towns and rural areas surrounding Greenville are seventy-seven more churches. This is a land of small roadside signs reminding you that Jesus is Lord. It’s also a land where about 40 percent of the population consists of married households, and where the median household income is around $31,000. In descending popularity, Pitt County residents work in textile manufacturing, health care, and retail industries. In greater Pitt County, agriculture, specifically soy and cotton farming, is still a big deal. And although the university, the hospital, and the pharmaceutical companies are attracting college-educated employees, the formal education of most Pitt County residents stops with high school diplomas. The vote on the 2012 election went to Barack Obama here, but by a slim margin: 53 percent.

Don Wilkerson is an avid golfer, a fan of health-club circuit training, and a joker, too. He is met with surprise by a lot by people who find his personality to be more vital than they expected of a funeral director. Some of his jokes run toward the bawdy. He’s not above explaining his business philosophy to a Young Lady Writer, for example, with an allegory passed down from his father. “He said, ‘Son? You have a business and you treat it like a lady? You put it up on the pedestal, you admire it, you treat it gently, and you give everything and you take last? Your business will look after you. But on the other case, if you treat a business like a whore, you take everything from it, you won’t have much.’”

Like his family’s business, Don Wilkerson fits inside the social and historical milieu of this land as a Russian doll is seated in its shell, following both its progress and its history exactly. He can point first to his grandfather, the charismatic coroner, followed by the next generation of owners, his father and uncles. All belonged to different churches—Don can tell you which—and were, respectively, a Kiwanian, a Rotarian, a Lion, and a member of the American Legion. They bought cars at different dealerships and sat on different civic boards, every single one of these moves motivated by both real community investment and marketing savvy, each a son grasping a thread and weaving his own upstanding reputation and that of the business into the community’s fabric. The same can be said of Don’s generation and that of his children. Always a staff of three to four funeral directors; always a Wilkerson.

When we’re through and he walks me out, he recommends a good new Thai restaurant up in Chapel Hill, if I should find myself out there anytime soon. Then he shakes my hand and gives his regards to my grandmama. Outside Wilkerson’s, the sudden bright sun and sounds of Greenville lunch-hour traffic overwhelm for a moment, before I regain my bearings and head out into the mundane world.