OPEN: 1932–1986

LOCATION: 4101 Wilshire Boulevard Los Angeles, CA 90010

ORIGINAL PHONE: FEderal-1221 and DU 3-1221

CUISINE: French-Italian

DESIGN: Paul Revere Williams

BUILDING STYLE: Vogue Regency

CURRENTLY: Perino’s Luxury Apartments

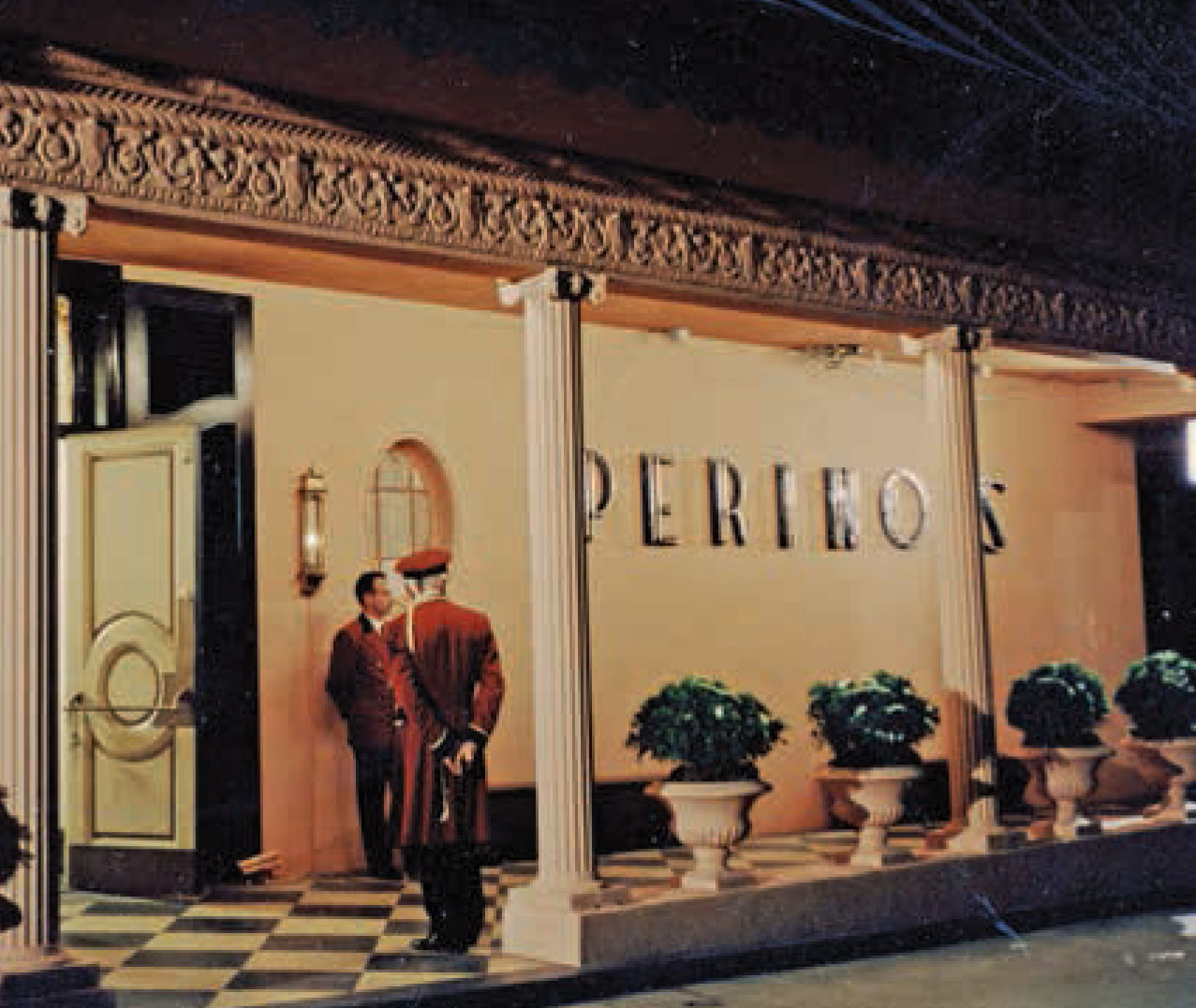

The entrance to Perino’s.

ALEXANDER PERINO, THE YOUNGEST OF TWELVE CHILDREN, WAS BORN IN THE PIEDMONT REGION OF ITALY IN 1895. He idolized his father, a winemaker, who died when Perino was only thirteen.

When Perino’s mother sent him to apprentice at a pastry shop on the Italian Riviera, it was the beginning of a love for food that would eventually lead him to become a famous restaurateur. Two years later, Perino’s mother passed away, and he boarded a ship headed for New York City.

For the next two decades, Perino worked his way westward through a variety of establishments in the U.S., from Delmonico’s in New York City, to the Plaza, to Chicago’s Congress Hotel, to Cleveland’s Hotel Deshler. His English became so good that his voice lost every trace of his original Italian accent. By 1925, he had reached Los Angeles, where he worked briefly at the newly opened Biltmore Hotel but was fired after dropping a tray of tea and crumpets. After becoming head waiter at the posh Victor Hugo’s, he realized that he could do better. So, with a $2,000 loan, he opened Perino’s in 1932, in the midst of the Great Depression. A few days after opening, he hired chef Attilio Balzano, beginning a thirty-seven-year culinary relationship.

In 1934, a grease fire in the Perino’s kitchen sent its patrons running for safety, escorted by Perino himself. By 1935, the kitchen had been rebuilt and was up and running again. The restaurant expanded even more in the early 1950s when it moved to its new location at 4101 Wilshire Boulevard, designed by Paul Revere Williams. The main dining room and two private dining rooms could seat 360 people at a time.

The restaurant suffered another fire in 1954, this one reportedly started by a lit cigarette that landed on an upholstered chair. In February 1955, the resilient Perino’s reopened once again. For the twenty years that followed, high society luncheons, pre-theater and pre-sporting event dinners, and elegant birthday and engagement parties were held at the restaurant. Perino’s was known for its wealthy patrons. Dorothy Chandler even visited the restaurant with hopes that diners would give donations for the construction of the Music Center.

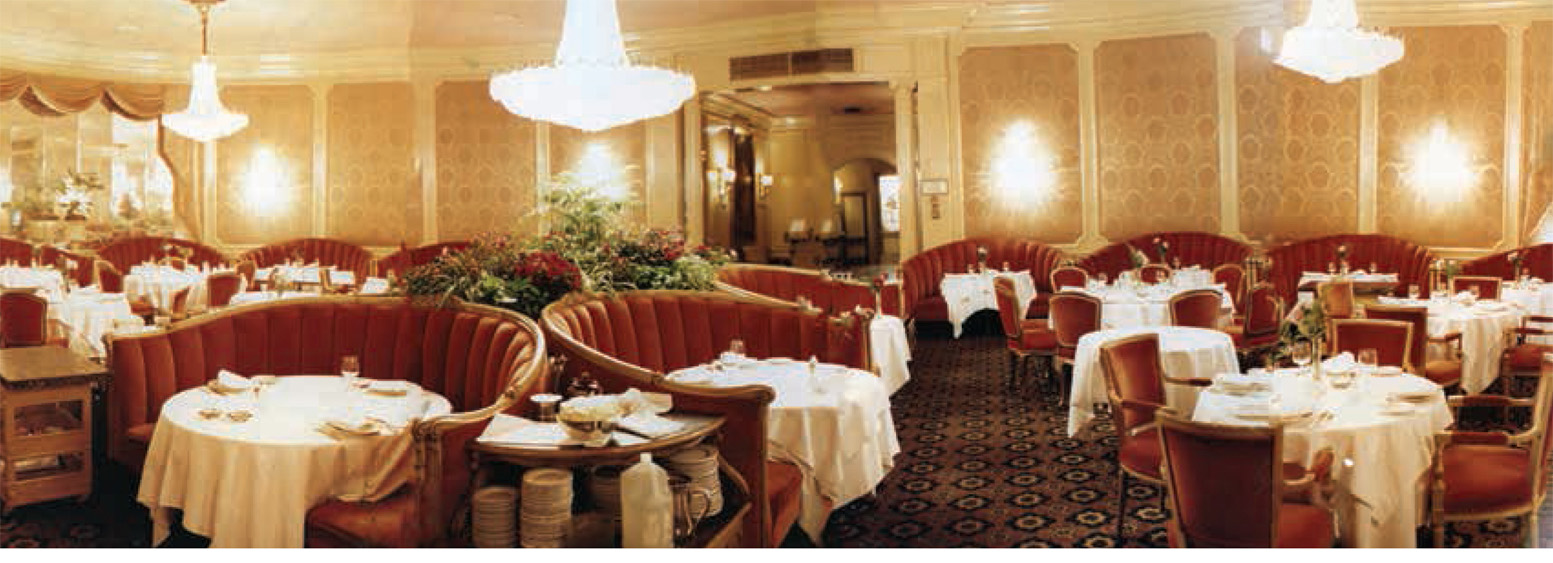

The elegant dining room at Perino’s, 1980s.

Perino’s sugar cubes.

The restaurant’s very large menu included more than 150 entrées and 270 wines. Perino had very high standards for the food served in his restaurant. “Food, service, cleanliness, and no cheating” was his motto. He also believed that “the best service is that which is never seen.” He never served food that had been frozen and discouraged excessive seasoning, preferring natural flavors and simplicity. “A salad,” he said, “should be like a beautiful woman in a plain dress.”

Perino’s standards were just as exacting for everything from the bar, to the tableware, to the music. Ice for the drinks was taken directly from the freezer to the bartender, so it would not inadvertently absorb flavors or scents from the kitchen. Serving from glass dishes was forbidden; Perino felt that glass was not as appealing to the eye, and could break easily. Every detail was carefully considered, from the silver-plated serving dishes, to the solid silver pastry cart, to the pink Irish linen napkins and tablecloths. Every table was decorated with a vase containing a single pink rose.

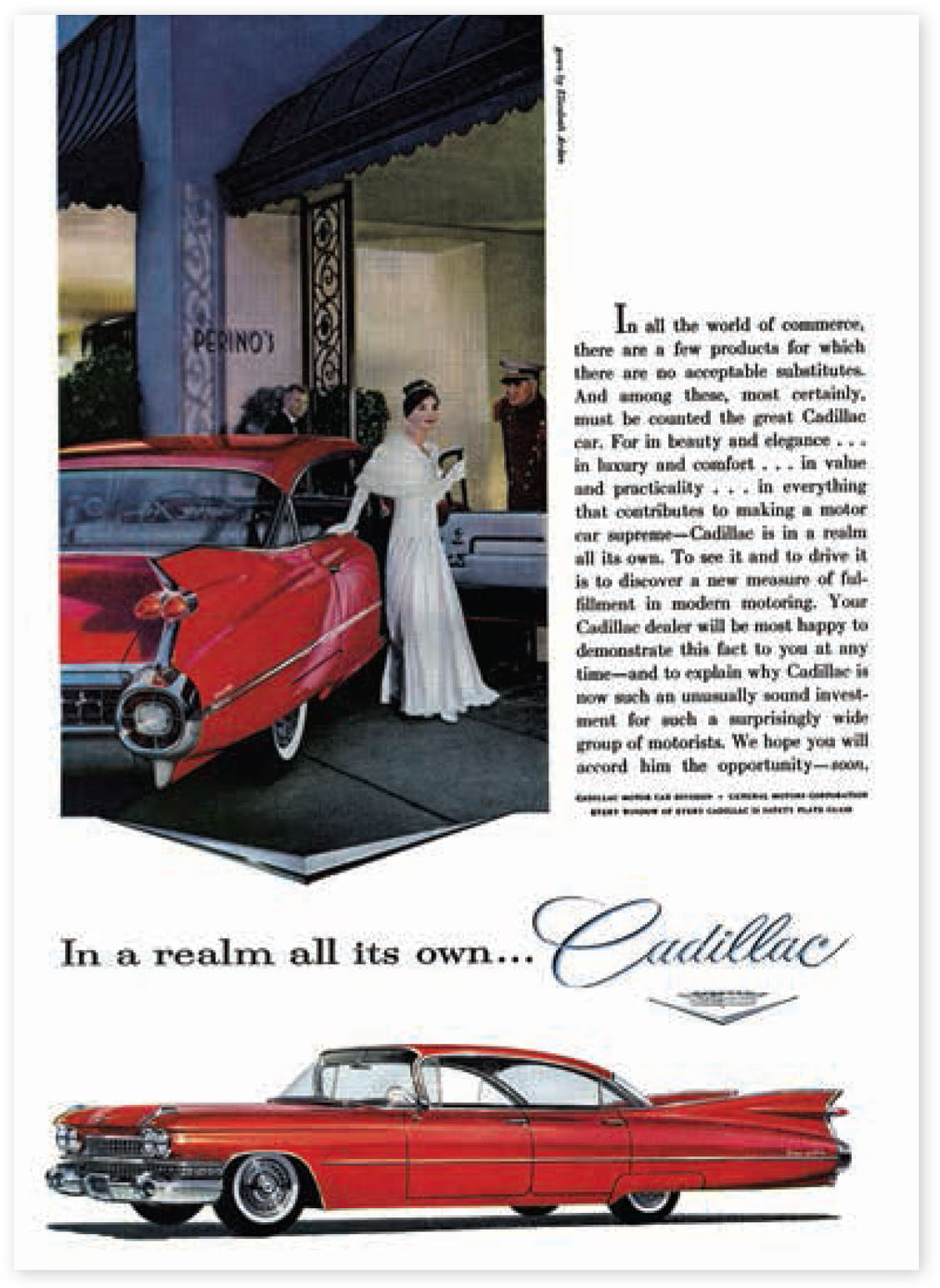

Cadillac advertisement featuring Perino’s, 1959.

The restaurant’s location, close to the Brown Derby and the Ambassador Hotel, drew Hollywood celebrities and the “blue blood” elite from the neighboring Hancock Park, where the city’s old money lived at the time. Stars like Frank Sinatra, who played the Steinway at the bar, provided entertainment from time to time. One table was permanently reserved for Bette Davis. Mae West, who lived close by at the Ravenswood Apartments, ate at Perino’s with her manager every Sunday. Bugsy Siegel was a regular and had a booth in the back of the restaurant, where he could see everyone and still not draw much attention. Cary Grant liked to sit close to the bar. Cole Porter reportedly wrote a song on the back of a Perino’s menu. Perino himself once taught Ronald Coleman how to make salad dressing. Other regulars included Joan Crawford, Spencer Tracy, ZaSu Pitts, Eleanor Roosevelt, Elizabeth Taylor, Irene Dunne, Howard Hughes, Fred Astaire, Cary Grant, and Gary Cooper.

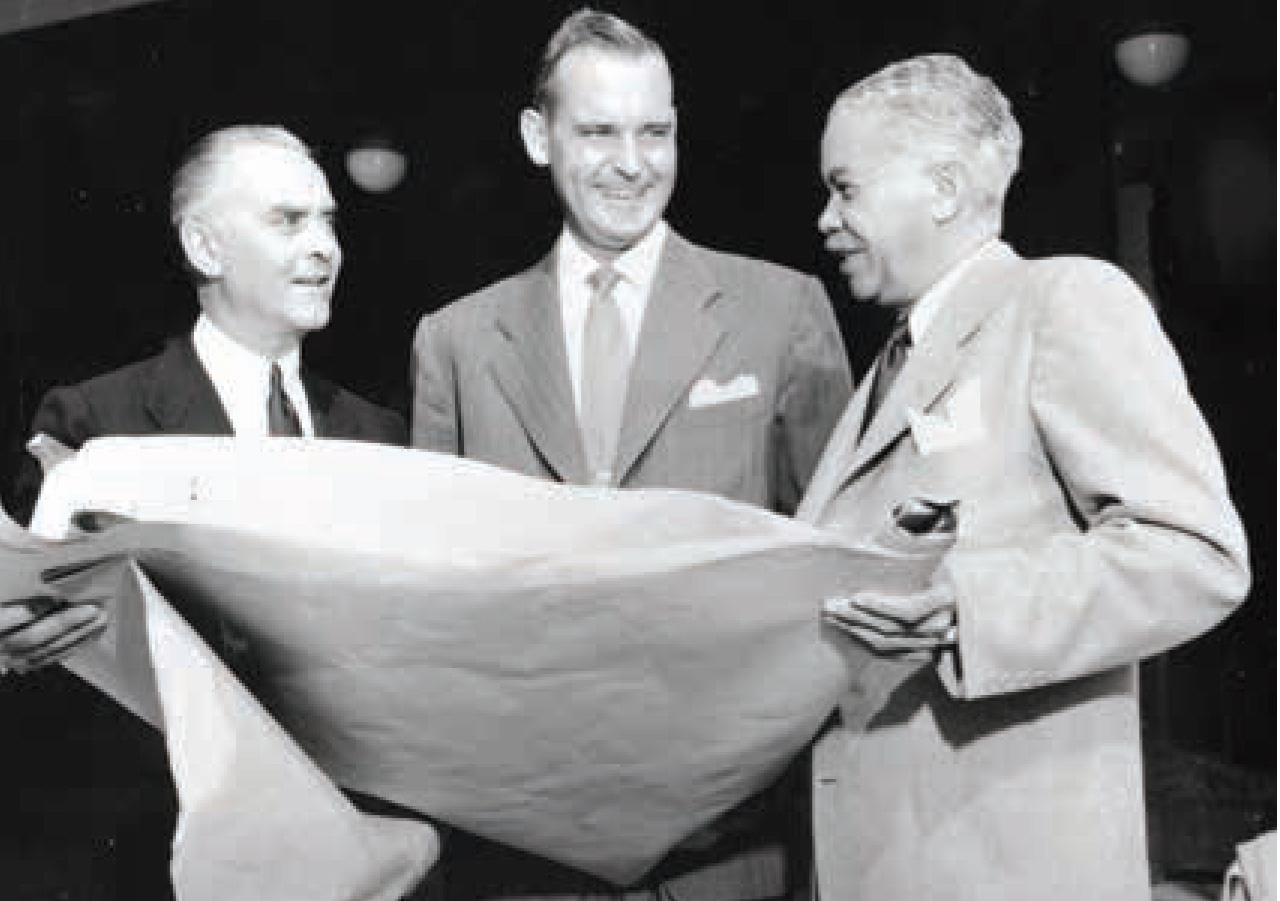

Alexander Perino with architect Paul Revere Williams (right), 1949.

George Burns with Gracie Allen (right) and a friend, 1959.

The restaurant was sold to Frank Esgro, Inc. in 1969, with the understanding that Perino would remain in charge. This agreement didn’t last, and Perino left, taking Chef Balzano with him. Esgro ran the restaurant until 1983. In 1985, he tried to open a downtown Los Angeles Perino’s location, but it failed to the tune of $7.5 million.

Perino died on New Year’s Day in 1982, at the age of eighty-six. The restaurant closed soon after, in 1986. For nine years after it closed, the restaurant served as a filming location for more than 200 productions. The dining room was perfect for filming because it was large enough to accommodate cameras and lighting equipment, and the room’s soft colors provided a flattering background. The restaurant was also used as a private banquet hall for events after its neighbor, the Ambassador, closed down.

In 2005, an auction took place for all of the items left at the restaurant, including the Steinway that Sinatra had played, Tyrone Power’s favorite booth, and all of the silver platters that celebrities had eaten their meals off of. Before the auction, real estate developer Tom Carey and his partner, Tef Kutay, bought the building and its contents for $4 million. They spent $20 million to construct a forty-seven-unit luxury apartment building named Perino’s Condominiums (later to become Perino’s Luxury Apartments). The foyer, name, logo, and distinctive entryway awning were incorporated into the complex.

![]()

Barbara Nichols and Dana Andrews, 1956.