The Terror of the Plague

PART I

You have seen the City as it appeared to one who walked about its streets and watched the people. It was free, busy and prosperous, except at rare intervals, when its own internal dissensions, or the civil wars of the country, or the pretensions of the Sovereign, disturbed the peace of the City. Behind this prosperity, however, lay hid all through the middle ages, and down to two hundred years ago, four great and ever-present terrors. The first was the Terror of Leprosy: the second the Terror of Famine: the third was the Terror of Plague: the last was the Terror of Fire.

CIVIL COSTUME ABOUT 1620

(From a contemporary broadside.)

COSTUME OF A LAWYER

(From a broadside, dated 1623.)

As for the first two, we have seen how lazar houses were established outside every town, and how public granaries were built. Let us consider the third. The Plague broke out so often that there was hardly any time between the tenth and the seventeenth century when some living person could not remember a visitation of this awful scourge. It appeared in London first - i.e. the first mention of it occurs in history - in the year 962: again in 1094: again in 1111: then there seems to have been a respite for 250 years. In the year 1348 the Plague carried off many thousands: in 1361 it appeared again: in 1367 and in 1369. In 1407 30,000 were carried off inLondon alone by the Plague. In 1478 a plague raged throughout the country, which was said to have destroyed more people than the Wars of the Roses. But we must accept all mediæval estimates of numbers as indicating no more than great mortality. With the sixteenth century began a period of a hundred and sixty years, marked with attacks of the Plague constantly recurring, and every time more fatal and more widespread. Nothing teaches the conditions of human life more plainly than the history of the Plague in London. We are placed in the world in the midst of dangers, and we have to find out for ourselves how to meet those dangers and to protect ourselves. Thus a vast number of persons were crowded together within the walls of the City. The streets were all narrow: the houses were generally of three or more stories, built out in front so as to obstruct the light and air; there were many courts, in which the houses were mere hovels: there was no drainage: refuse of all kinds lay about the streets: everything that was required for the daily life was made in the City, which added a thousand noisome smells and noxious refuse. Then the Plague came and carried off its thousands and disappeared. Then the survivors went on their usual course. Nothing was changed. Yet the Plague was a voice which spoke loudly. It said ‘Clean yourselves: cease to defile the soil of the City with your decaying matter: build your houses in wider streets: do not shut out the sunshine - which is a splendid purifier - or light and air. Keep yourselves clean - body and raiment, and house and street.’ The voice spoke, but no one heard. Then came the Plague again. Still no one heard the voice. It came again and again. It came in 1500, in 1525, in 1543, in 1563, in 1569, in 1574, in 1592, in 1603 (when 30,575 died), in 1625 (when 35,470 died), in 1635 (when 10,400 died), and lastly, in 1665. And in all that time no one understood that voice, and the City was never cleansed. All that was done was to light bonfires in the street in order to increase the circulation of the air. After the last, and worst attack, in 1666 the City was burned, and in the purification of the flames it emerged clean, and the Plague has never since appeared. The same voice speaks to mankind still in every visitation of every new pestilence. It used to cry aloud in time of Plague: it cries aloud now in time of typhoid, diphtheria, and cholera. Diseases spring from ignorance and from vice. Physicians cannot cure them: but they can learn their cause and they can prevent.

The Plague of 1665 began in the autumn of the year before. It had been raging in Amsterdam and Hamburg in 1663. Precautions were taken to keep it out by stopping the importation of goods from these towns. But these proved ineffectual. Certain bales from Holland were landed and taken to a house in Long Acre, Drury Lane. Here they were opened by two Frenchmen, both of whom caught the disease and died. A third Frenchman who was seized in the same house was removed to Bearbinder Lane, St. Swithin’s Lane, where he, too, died. And then the disease began to spread. A severe frost checked it for a time. But in March, when milder weather returned, it broke out again.

The disease, when it seized upon a person, brought upon him a most distressing horror of mind. This was followed by fever and delirium. But the certain signs of the plague were spots, pustules, and swellings, which spread over the whole body. Death in most cases rapidly followed. Some there were who recovered, but the majority gave themselves over for lost on the first appearance. Many of the physicians ran away from the infected City: many of the parish clergy deserted their churches. The Lord Mayor and Aldermen, however, remained, by their presence giving heart to those of the clergy and physicians who stayed, and by their prudent measures preventing a vast amount of additional suffering which would otherwise have fallen upon the unhappy people.

PART II

In the month of May it was found that twenty City parishes were infected. Certain preventions, rather than remedies, of which there were none, were now employed by the Mayor. Infected houses were shut up: no one was allowed to go in or to come out: food was conveyed by buckets let down from an upper window: the dead bodies were lowered in the same way, from the windows: on the doors were painted red crosses with the words, ‘Lord, have mercy upon us!’ Watchmen were placed at the doors to prevent the unhappy prisoners from coming out. All the dogs and cats in the City, being supposed to carry about infection in their fur or hair, were slaughtered - 40,000 dogs, it is stated, and 200,000 cats, which seems an impossible number, were killed. They also tried, but without success, to kill the rats and mice. Everything was tried except the one thing wanted - air and cleanliness. At the outset a great many of the better sort left the City and stayed in the country till the danger was over: others would have followed but the country people would not suffer their presence and drove them back with clubs and pikes. So they had to come back and die in the City. Then all the shops closed: all industries were stopped: men could no longer sit beside each other: the masters dismissed their apprentices and their workmen and their servants. In the river the ships lay with their cargoes half discharged: on the quays stood the bales, unopened. In the churches there were no services except where the scanty congregation sat singly and apart. The Courts of Justice were empty: there were no crimes to try: in the streets the passengers avoided each other. In the markets which had to be kept open, the buyer lifted down his purchase with a hook and dropped the money into a bowl of vinegar. Many families voluntarily shut their houses and would neither go in or out. Some of these escaped the infection; the history of one such family during their six months’ imprisonment has been preserved. They thanked God solemnly every morning for continued health: they prayed three times a day for safety. Some went on board ship and, as the Plague increased, dropped down the river.

A COUNTRYMAN. A COUNTRYWOMAN.

ORDINARY CIVIL COSTUME; temp. CHARLES I

(From Speed’s map of ‘The Kingdom of England,’ 1646.)

The deaths, which in the four weeks of July numbered 725, 1,089, 1,843, and 2,010, respectively, rose in August and September to three, four, five, and even eight thousand a week: but it was believed that the registers were badly kept and that the numbers were greater than appeared. Every evening carts were sent round, the drivers who smoked tobacco as a disinfectant, crying out, ‘Bring out your Dead. Bring out your Dead,’ and ringing a bell. The churchyards were filled and pits were dug outside the City into which the bodies were thrown without coffins. When the pestilence ceased the churchyards were covered with a thick deposit of fresh mould to prevent ill consequences. It was observed that during the prevalence of the disease there was an extraordinary continuance of calm and serene sunshine. For many weeks together not the least breath of wind could be perceived.

When the summer was over and the autumn came on, the disease became milder in its form: it lasted longer: and whereas, at the first, not one in five recovered, now not two in five died. Presently the cold weather returned and the Plague was stayed. They burned or washed all the linen, flannel, clothes, bedding, tapestry and curtains belonging to the infected houses: and they whitewashed the rooms in which the disease had appeared. But they did not take steps for the cleansing of the City. The voice had spoken in vain. The number of deaths during the year was registered as 97,306 of which 68,596 were attributed to the Plague. But there seems little doubt that the registers were inefficiently kept. It was believed that the number who perished by Plague alone was at least 100,000.

It is easy to write down these figures. It is difficult to understand what they mean. Among them, a quarter at least, would be the breadwinners, the fathers of families. In many cases all perished together, parents and children: in others, the children were left destitute. Then there was no work. There were 100,000 working men out of employment. All these people had to be kept. The Lord Mayor, assisted by his Aldermen and two noble Lords, Albemarle and Craven, organised a service of relief. The King gave a thousand pounds a week: the City gave 600l. a week: the merchants contributed thousands every week. And so the people were kept from starving.

When it was all over Pepys, who kept his Diary through the time of the Plague but was not one of those who stayed in the infected City, notes the enormous number of beggars. Who should they be but the poor creatures, the women and the children, the old and the infirm who had lost their breadwinners, the men who loved them and worked for them? The history is full of dreadful things: but this amazing crowd of beggars is the most dreadful.

The Terror of the Fire

PART I

A CITIZEN. A CITIZEN’S WIFE.

ORDINARY CIVIL COSTUME; temp. CHARLES I

(From Speed’s map of ‘The Kingdom of England,’ 1646.)

The City of London has suffered from fire more than any other great town. In the year 961 a large number of houses were destroyed: in 1077, 1086, and 1093, a great part of the City was burned down. In 1136, a fire which broke out at London Stone, in the house of one Aylward, spread east and west as far as Aldgate on one side and St. Erkinwald’s shrine in St. Paul’s Cathedral on the other. London Bridge, then built of wood,perished in the fire, which for five hundred years was known as the Great Fire. In these successive fires every building of Saxon erection, to say nothing of the Roman period, must have perished.

But the ravages of all the fires together did less harm than the terrible fire which laid the greater part of London in ashes in the year 1666. If you will refer to the map of London you may mark off within the walls the North-East angle: that part contained by the wall and a straight line running from Coleman Street to Tower Hill. With the exception of that corner the whole of London within the walls, and beyond as far as the Temple, was entirely destroyed.

The fire broke out at a baker’s in Pudding Lane, Thames Street. It was early on Sunday morning on the second day of September, 1666. It was then, and is now, a place where the houses stood very thick and close together: all round were warehouses filled with oil, wine, tar, and every kind of inflammable stuff. The baker’s shop contained a large quantity of faggots and brushwood, so that the flames caught and spread very rapidly. The people, for the most part, had time to remove their most valuable things, but their furniture, their clothes, the stock of their shops, the tools of their trade, they had to leave behind them. Some hurriedly placed their things in the churches for safety, as if the fire would respect the sanctity of these buildings. A stranger Sunday was never spent than this, when those who had escaped were asking where to go, and those upon whom the flames were advancing were tearing out of their houses whatever they could carry away, and the rest of the town were looking on and asking whether the flames would be stayed before they reached their houses.

Among those who thought that a church would be a safe place were the booksellers of Paternoster Row. They carried all their books into St. Paul’s Cathedral and retired - their stock in trade was safe. But the flames closed round upon the Cathedral: they seized on Paternoster Row, so that the booksellers like the rest were fain to fly: and presently towering to the sky flamed up the lofty roof of nave and chancel and tower. Then with an awful crash the flaming timbers fell down into the church below. Even the Cathedral was burned with the rest, and with it all the books.

A GENTLEMAN. A GENTLEWOMAN

A GENTLEMAN. A GENTLEWOMAN

ORDINARY CIVIL COSTUME; temp. CHARLES I

(From Speed’s map of ‘The Kingdom of England,’ 1646.)

All Sunday, Monday, Tuesday and part of Wednesday, the fire raged, till it seemed as if there would be no end until the City was utterly destroyed. Happily a remnant was saved, as you have seen. The fire was stopped at last by blowing up houses everywhere to arrest its progress. Close by the Temple Church (which barely escaped) they stopped it in this way. At Aldersgate, Cripplegate, and Bishopsgate, they used the same means, and at Pye Corner, Smithfield. Nearly opposite Bartholomew’s Hospital, you may still see the image of a boy set up to commemorate the stopping of the fire at that point. Had it gone further we should have lost St. Bartholomew the Great and the houses of Cloth Fair.

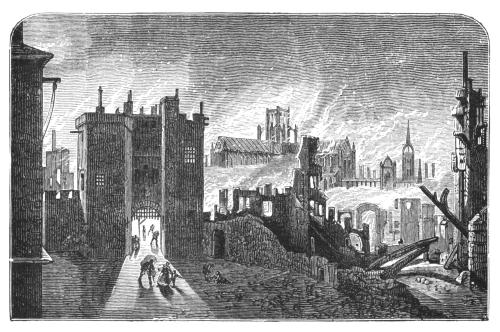

LUDGATE ON FIRE

When the fire stopped the people sat down to consider the losses they had sustained and the best way out of them.

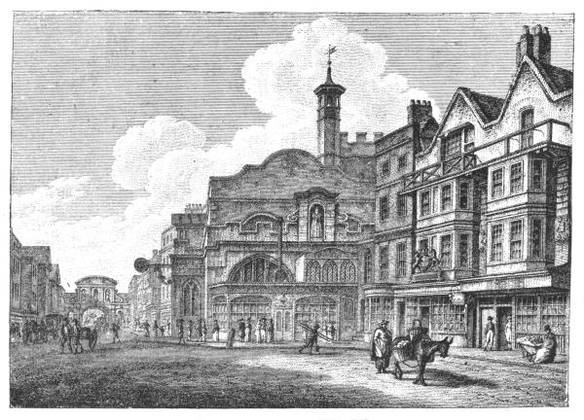

St. Paul’s Cathedral, that ancient and venerable edifice, with its thick walls and roof so lofty, that it seemed as if no fire but the fire from heaven could reach it, was a pile of ruins, the walls of the nave and transept standing, the choir fallen into the crypt below. The Parish churches to the number of 88 were burned: the Royal Exchange - Gresham’s Exchange - was down and all the statues turned into lime, with the exception of Gresham’s alone: nearly all the great houses left in the City, the great nobles’ houses, such as Baynard’s Castle, Coldharbour, Bridewell Palace, Derby House, were in ashes: all the Companies’ Halls were gone: warehouses, shops, private residences, palaces and hovels - everything was levelled with the ground and burned to ashes. Five-sixths of the City were destroyed: an area of 436 acres was covered with the ruins: 13,200 houses were burned: it is said that 200,000 persons were rendered homeless - an estimate which would give an average of 15 residents to each house. Probably this is an exaggeration. The houseless people, however, formed a kind of camp in Moorfields just outside the wall, where they lived in tents, and cottages hastily run up. The place now called Finsbury Square stands on the site of this curious camp.

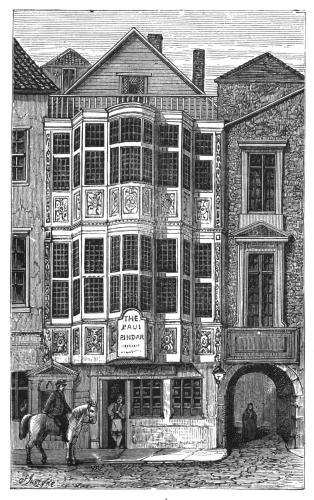

PAUL PINDAR’S HOUSE

We ask ourselves in wonder how life was resumed after so great a calamity. The title deeds to houses and estates were burned - who would claim and prove the right to property? The account books were all lost - who could claim or prove a debt? The warehouses and shops with their contents were gone - who could carry on business? The craftsmen had lost their employment - how were they to live?

Of debts and rents and mortgages and all such things, little could be said. It was not a time to speak of the past. They must think of the future: they must all begin the world anew.

PART II

They must begin the world anew. For most of the merchants nothing was left to them but their credit - their good name: try to imagine the havoc caused by burning all the docks, warehouses, wharves, quays, and shops in London at the present day with nothing at all insured!

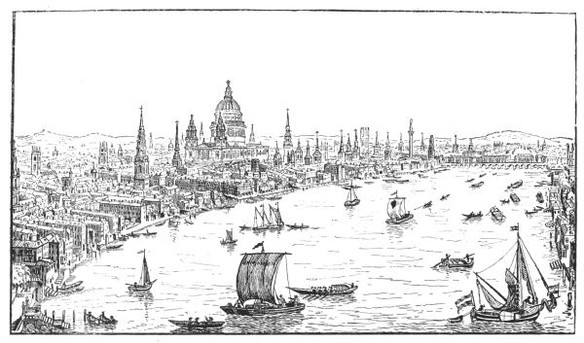

LONDON, AS REBUILT AFTER THE FIRE

But the citizens of London were not the kind of people to sit down weeping. The first thing was to rebuild their houses. This done there would be time to consider the future. The Lord Mayor and the Aldermen took counsel together how to rebuild the City. They called in Sir Christopher Wren, lately become an architect after being astronomer at Cambridge, and Evelyn: they invited plans for laying out the City in a more uniform manner with wider streets and houses more protected from fire. Both Wren and Evelyn sent in plans. But while these were under consideration the citizens were rebuilding their houses.

They did not wait for the ashes to get cool. As soon as the flames were extinct and the smoke had cleared: as soon as it was possible to make way among the ruined walls, every man sought out the site of his own house and began to build it up again. So that London, rebuilt, was almost - not quite, for some improvements were effected - laid out with the same streets and lanes as before the fire. It was two years, however, before the ruins were all cleared away and four years before the City was completely rebuilt. Ten thousand houses were erected during that period, and these were all of brick: the old timbered house with clay between the posts was gone: so was the thatched roof: the houses were all of brick: the roofs were tiled: the chief danger was gone. At this time, too, they introduced the plan of a pavement on either side of smooth flat stones with posts to keep carts and waggons from interfering with the comforts of the foot passengers. It took much longer than four years to erect the Companies’ Halls. About thirty of the churches were never rebuilt at all, the parishes being merged in others. The first to be repaired, not rebuilt, was that of St. Dunstan’s two years after the fire: in four years more, another church was finished. In every year after this one or two: and the last of the City churches was not rebuilt till thirty one years after the fire.

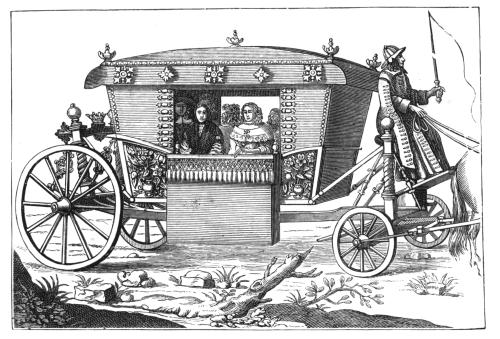

COACH OF THE LATTER HALF OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY.

(From Loggan’s ‘Oxonia Illustrata.’)

WAGGON OF THE SECOND HALF OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY.

(From Loggan’s ‘Oxonia Illustrata.’)

It was at this time of universal poverty that the advantages of union was illustrated to those who had eyes to see. First of all, the Corporation had to find food - therefore work. Thousands were employed in clearing away the rubbish and carting it off so as to make the streets, at least, free for traffic. The craftsmen who had no work to do, were employed when this was done on the building operations. The quays were cleared, and the warehouses put up again, for the business of the Port continued. Ships came, discharged their cargoes, and waited for their freight outward bound. Then the houses arose and the shops began to open again. And the Companies stood by their members: they gave them credit: advanced loans: started them afresh in the world. Had it not been for the Companies, the fate of London after the fire would have been as the fate of Antwerp after the Religious Wars. But there must have been many who were ruined completely by this fearful calamity. Hundreds of merchants, and retailers, having lost their all must have been unable to face the stress and anxiety of making this fresh start. The men advanced in life; the men of anxious and timid mind; the incompetent and feeble: were crushed. They became bankrupt: they went under: in the great crowd no one heeded them: their sons and daughters took a lower place: perhaps they are still among the ranks into which it is easy to sink; out of which it is difficult to rise. The craftsmen were injured least: their Companies replaced their tools for them: work was presently resumed again: their houses were rebuilt and, as for their furniture, there was not much of it before the fire and there was not much of it after the fire.

The poet Dryden thus writes of the people during and after the fire:

Those who have homes, when home they do repair,To a last lodging call their wandering friends:Their short uneasy sleeps are broke with careTo look how near their own destruction tends.

Those who have none sit round where once it wasAnd with full eyes each wonted room require:Haunting the yet warm ashes of the place,As murdered men walk where they did expire.

The most in fields like herded beasts lie down,To dews obnoxious on the grassy floor:And while the babes in sleep their sorrow drown,Sad parents watch the remnant of their store.

ORDINARY DRESS OF GENTLEMEN IN 1675

(From Loggan’s ‘Oxonia Illustrata.’)

Rogues and Vagabonds

The aspect of the City varies from age to age: the streets and the houses, the costumes, the language, the manners, all change. In one respect however, there is no change: we have always with us the same rogues and the same roguery. We do not treat them quite after the manner followed by our forefathers: and, as their methods were incapable of putting a stop to the tricks of those who live by trickery, so are ours; therefore we must not pride ourselves on any superiority in this direction. A large and very interesting collection of books might be formed on the subject of rogues and vagabonds. The collection would begin with Elizabeth and could be carried on to the present day, new additions being made from year to year. But very few additions are ever made to the customs and the methods of the profession. For instance, there is the confidence trick, in which the rustic is beguiled by the honest stranger into trusting him. This trick was practised three hundred years ago. Or there is the ring-dropping trick, it is as old as the hills. Or there is the sham sailor - now very rarely met with. When we have another war he will come to the front again. We have still the cheating gambler, but he has always been with us. In King Charles the Second’s time he was called a Ruffler, a Huff, or a Shabbaroon. The woman who now begs along the streets singing a hymn and leading borrowed children, did the same thing two hundred years ago and was called a clapperdozen. The man who pretends to be deaf and dumb went about then, and was known as the dummerer. The burglar was then the housebreaker. Burglary was formerly a far worse crime than it is now, because the people for the most part kept all their money in their houses, and a robbery might ruin them. The pickpocket plied his trade, only he was then a cutpurse. The footpad lay in wait on the lonely country road or among the bushes of the open fields at the back of Lincoln’s Inn. The punishments, which seem so mild under the Plantagenets, increased in severity as the population outgrew the powers of the government. Instead of plain standing in pillory, ears were nailed to the post and even sliced off: whippings became more commonly administered, and were much more severe: heretics were burned by Elizabeth as well as by Mary, though not so often. After the civil wars we enter upon a period when punishment became savage in its cruelty, of which you will presently learn more. Meantime remark that when the City was less densely populated, and when none lived outside the wards and walls, the people were well under the control of the aldermen and their officers: they were also well known to each other: they exercised that self-government - the best of any - which consists in refusing to harbour a rogue among them. If in every London street the tenants would refuse to suffer any evildoer to lodge in their midst, the police of London might be almost abolished. But the City grew: the wards became densely populated: then houses and extensive suburbs sprang up at Whitechapel, Wapping, outside Cripplegate, at Smithfield north of Fleet Street, Lambeth, Bermondsey and Rotherhithe: the aldermen no longer knew their people: the men of a ward did not know each other: rogues were harboured about Smithfield and outside Aldgate: the simple machinery for enforcing order ceased to be of any use: and as yet the new police was not invented. Therefore the punishments became savage. Since the government could not prevent crime and compel order, they would deter.

DRESS OF LADIES OF QUALITY

(From Sandford’s ‘Coronation Procession of James II.’)

ORDINARY ATTIRE OF WOMEN OF THE LOWER CLASSES

(From Sandford’s ‘Coronation Procession of James II.’)

Apart from active crime, vagrancy was a great scourge. Wars and civil wars left crowds of idle soldiers who had no taste for steady work: they became vagrants: there was also - and there is still - a certain proportion of men and women who will not work: they become vagrants by a kind of instinct: they are born vagabonds. Laws and proclamations were continually passed for the repression of vagrants. They were passed on to their native place: they were provided with passes on their way. But these laws were always being evaded, and vagrants increased in number. Under Henry VIII. a very stringent statute was passed by which old and impotent persons were provided with license to beg, and anybody begging without a license was whipped. But like all such acts it was imperfectly carried out. For one who received a whipping a dozen escaped. Stocks, pillory, bread and water, all were applied, but without visible effect, because so many escaped. London especially swarmed with beggars and pretended cripples. They lived about Turnmill Street, Houndsditch and the Barbican, outside the walls. From time to time a raid was carried on against them, and they dispersed, but only to collect again. In the year 1575, for instance, it is reported that there were few or no rogues in the London prisons. But in the year 1581, the Queen observing a large number of sturdy rogues during a drive made complaint, with the result that the next day 74 were arrested: the day after 60, and so on, the catch on one day being a hundred, all of whom were ‘soundly paid,’ i.e. flogged and sent to their own homes. The statute ordering the whipping of vagabonds was enforced even in this present century, women being flogged as well as men. No statutes, however, can put down the curse of vagrancy and idleness. It can only be suppressed by the will and resolution of the people themselves. If for a single fortnight we should all refuse to give a single penny to beggars: if in every street we should all resolve upon having none but honest folk among us: then and only then, would the rogue find this island of Great Britain impossible to be longer inhabited by him and his tribe.

Under George the Second

PART I

The Wealth of London

If a new world was opened to the adventurous in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, this new world two hundred years later was only half explored and was constantly yielding up new treasures. The lion’s share of these treasures came to Great Britain and was landed at the Port of London. The wealth and luxury of the merchants in the eighteenth century surpassed anything ever recorded or ever imagined. So great was their prosperity that historians and essayists predicted the speedy downfall of the City: the very greatness of their success frightened those who looked on and remembered the past.

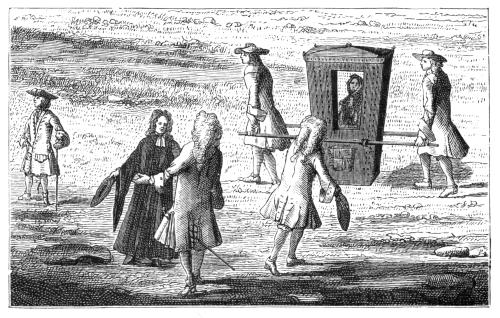

GROUP SHOWING COSTUMES AND SEDAN CHAIR, ABOUT 1720

(From an engraving by Kip.)

Though the appearance of the City had changed, and its colour and picturesqueness were gone, at no time was London more powerful or more magnificent. There were no nobles living within the walls: only two or three of the riverside palaces remained along the Strand: there were no troops of retainers riding along the streets in the bright liveries of their masters: the picturesque gables, the latticed windows, the overhanging fronts - all these were gone: instead of the old churches rich with ancient carvings, frescoes in crimson and blue, marble monuments and painted glass, were the square halls - preaching halls - of Wren with their round windows, rich only in carved woodwork: the houses were square with sash windows: the shop fronts were glazed: the streets were filled with grave and sober merchants in great wigs and white ruffles. They lived in stately and commodious houses, many of which still survive - see the Square at the back of Austin Friars Church for a very fine example - they had their country houses: they drove in chariots: and they did a splendid business. Their ships went all over the world: they traded with India, not yet part of the Empire: with China, and the Far East: with the West Indies, with the Levant. They had Companies for carrying on trade in every part of the globe. The South Sea Company, the Hudson’s Bay Company, the Turkey Company, the African Company, the Russian Company, the East India Company - are some. The ships lay moored below the Bridge in rows that reached a mile down the river.

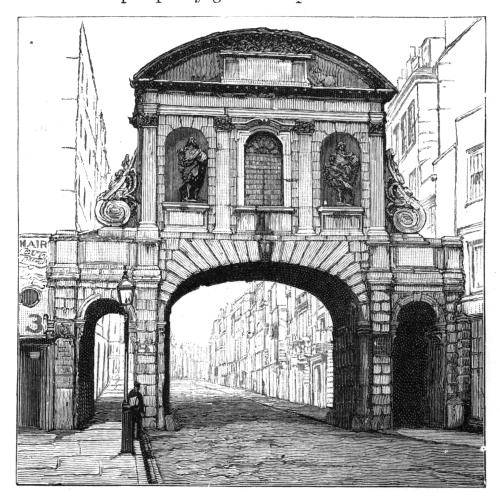

TEMPLE BAR, LONDON

(Built by Sir Christopher Wren in 1670; taken down in 1878 and since rebuilt at Waltham Cross.)

All this prosperity grew in spite of the wars which we carried on during the whole of the last century. These wars, though they covered the Channel and the Bay of Biscay with privateers, had little effect to stay the increase of London trade. And as the merchants lived within the City, in sight of each other, their wealth was observed and known by all. At the present day, when London from nightfall till morning is a dead city, no one knows the wealth of the merchants and it is only by considering the extent of the suburbs that one can understand the enormous wealth possessed by those men who come up by train every day and without ostentation walk among their clerks to their offices in the City. A hundred and fifty years ago, one saw the rich men: sat in church with them: sat at dinner with them on Company feast days: knew them. The visible presence of so much wealth helped to make London great and proud. It would be interesting, if it were possible, to discover how many families now noble or gentle - county families - derive their origin or their wealth from the City merchants of the last century.

In one thing there is a great change. Till the middle of the seventeenth century it was customary for the rank of trade to be recruited - in London, at least - from the younger sons. This fashion was now changed. The continual wars gave the younger sons another career: they entered the army and the navy. Hence arose the contempt for trade which existed in the country for about a hundred and fifty years. It is now fast dying out, but it is not yet dead. Younger sons are now going into the City again.

FLEET STREET AND TEMPLE BAR

The old exclusiveness was kept up jealously. No one must trade in the City who was not free of the City. But the freedom of the City was easily obtained. The craftsman and the clerk remained in their own places: they were taught to know their places: they were taught, which was a very fine thing, to think much of their own places and to take pride in the station to which they were called: to respect those in higher station and to receiverespect from those lower than themselves. Though merchants had not, and have not, any rank assigned to them by the Court officials, there was as much difference of rank and place in the City as without. And in no time was there greater personal dignity than in this age when rank and station were so much regarded. But between the nobility and the City there was little intercourse and no sympathy. The manners, the morals, the dignity of the City ill assorted with those of the aristocracy at a time when drinking and gambling were ruining the old families and destroying the noblest names. There has always belonged to the London merchant a great respect for personal character and conduct. We are accustomed to regard this as a survival of Puritanism. This is not so: it existed before the arrival of Puritanism: it arose in the time when the men in the wards knew each other and when the master of many servants set the example, because his life was visible to all, of order, honour, and self-respect.

A COACH OF THE MIDDLE OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

(From an engraving by John Dunstall.)

PART II

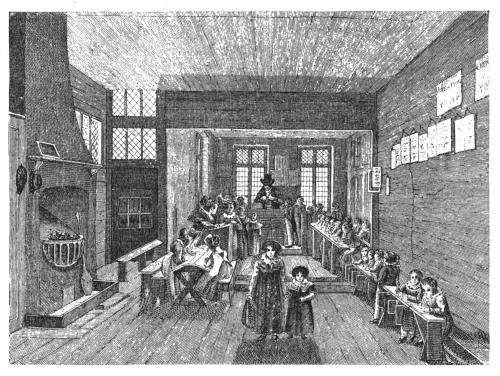

After the Great Fire, the number of City churches was reduced from 126 to 87. Those that were rebuilt were for the most part much larger and more capacious than their predecessors. In many cases, Wren, the great architect, who rebuilt St. Paul’s Cathedral and all the churches, in order to get a larger church took in a part of the churchyard, which accounts for the fact that many of the City churchyards are now so small. Again, as the old churches had been built mainly for the purpose of saying and singing mass, the new churches were built mainly for the purpose of hearing sermons. They were therefore provided with pews for the accommodation of the hearers, and resembled, in their original design, a convenient square room, where the preacher might be seen and heard by all, rather than a cruciform church. Some of Wren’s churches, however, though they may be described as square rooms, are exceedingly beautiful, for instance, St. Stephen’s, Walbrook, while nearly all are enriched with woodwork of a beautiful description. It was the custom in the last century to attend frequent church services, and to hear many sermons. The parish church entered into the daily life much more under George the Second’s reign than it does now, in spite of our improved services and our multiplication of services. In forty-four City churches there was service, sometimes twice, sometimes once, every day. In all of them there were evening services on Wednesday and Fridays: in many there were endowed lectureships, which gave an additional sermon once a week, or at stated times. Fast days were commonly observed, though it was not customary to close shops or suspend business on Good Friday or Ash Wednesday: not more than half of the City churches possessed an organ: on Sunday afternoons the children were duly catechised: if boys misbehaved, the beadle or sexton caned them in the churchyard: the laws were still in force which fined the parishioners for absence from church and for harbouring in their houses people who did not go to church. Except for Sunday services, sermons, and visitations of the sick, the clergy had nothing to do. What is now considered the work of the parish clergy - the work that occupies all their time - is entirely modern. Formerly this kind of work was not done at all; the people were left to themselves: the clergy were not the organisers of mothers’ meetings, country jaunts, athletics, boys’ clubs, and amusements. The Nonconformists still formed an important part of the City. They had many chapels, but their social influence in London, which was very great at the beginning of the century, declined steadily, until thirty or forty years ago it stood at a very low ebb indeed.

In the streets the roads were paved with round pebbles - they were ‘cobbled’: the footway was protected by posts placed at intervals: the paving stones, which only existed in the principal streets before the year 1766, were small, and badly laid: after a shower they splashed up mud and water when one stepped upon them. The signs which we have seen on the Elizabethan houses still hung out from every shop and every house: they had grown bigger: they were set in immense frames of ironwork, which creaked noisily, and sometimes tore out the front of a house by their enormous weight. The shop windows were now glazed with small panes, mostly oblong, and often in bow windows: you may find several such shops still remaining: one at the top of the Haymarket: one in Coventry Street: one in the Strand: there were no fronts of plate glass brilliantly illuminated to exhibit the contents exposed for sale: the old-fashioned shopkeeper prided himself on keeping within, and out of sight, his best and choicest goods. A few candles lit up the shop in the winter afternoons.

VIEW OF SCHOOL CONNECTED WITH BUNYAN’S MEETING HOUSE

To walk in the streets meant the encounter of roughness and rudeness which would now be thought intolerable. There were no police to keep order: if a man wanted order he might fight for it. Fights, indeed, were common in the streets: the waggoners, the hackney coachmen, the men with the wheelbarrows, the porters who carried things, were always fighting in the streets: gentlemen were hustled by bullies, and often had to fight them: most men carried a thick cudgel for self-protection.

The streets were far noisier in the last century than ever they had been before. Chiefly, this was due to the enormous increase of wheeled vehicles. Formerly everything came into the City or went out of it on the backs of pack-horses and pack-asses. Now the roads were so much improved that waggons could be used for everything, and the long lines of pack-horses had disappeared from the main roads. In the country lanes the pack-horse was still employed. Everybody was able to ride, and the City apprentice, when he had a holiday, always spent it on horseback. But for everyday the hackney coach was used. Smaller carts were also coming into use. And for dragging about barrels of beer and heavy cases a dray of iron, without wheels, was used. All these innovations meant more noise and still more noise. Had Whittington, in the time of George II., sat down on Highgate Hill (still a grassy slope), he would have heard, loud above the sound of Bow Bells, the rumbling of the waggons on Cheapside.

PART III

In walking through the City to-day, one may remark that there is very little crying of things to sell. In certain streets, as Broad Street, Whitecross Street, Whitechapel, or Middlesex Street, there is a kind of open street, fair, or market; but the street cries such as Hogarth depicted exist no longer. People used to sell a thousand things in the streets which are now sold in shops. All the little things - thread, string, pins, needles, small coal, ink, and straps - that are wanted in a house were sold by hawkers and bawled all day long in the streets: fruit of all kinds was sold from house to house: fish: milk: cakes and bread: herbs and drugs: brimstone matches: an endless procession passed along, all bawling their wares. Then there were the people who ground knives, mended chairs, soldered pots and pans: these bawled with the hawkers. We can no longer speak of the roar of London: there is no roar: the vehicles, nearly all provided with springs, roll smoothly over an even surface of asphalt: there are no more drays without wheels: there are no more street fights: there is comparatively little bawling of things to sell.

GRENADIER IN THE TIME OF THE PENINSULAR WAR

In those days people liked the noise. It was a part of the City life: it showed how big and busy the City was since it could make such a tremendous noise by the mere carrying on of the daily round. Could any other city - even Paris - boast of such a noise? People who came up from the country to visit London were invited to consider the noise of the City as a part of its magnificence and pride.

What else had they to consider? What were the sights of London?

First of all, St. Paul’s and Westminster Abbey. Then the Tower and the Monument, the Royal Exchange and the Mansion House, Guildhall and the Bank of England, London Bridge, Newgate, St. James’s and the Horse Guards. These were to be visited by day. In the evening there were the theatres, Drury Lane and Covent Garden: and there were the Gardens.

The citizens were always fond of their Gardens. They were opened as soon as the weather would allow, and they continued open till the autumn chills made them impossible. The gardens were those of Vauxhall - still in existence as a small park: Ranelagh, at Chelsea: Marylebone, opposite the old Parish Church in High Street: Bagnigge Wells, which lay East of Gray’s Inn Road: Belsize, near Hampstead: the White Conduit House in the fields near Islington: the Florida Gardens at Brompton: the Temple of Flora, the Apollo Gardens, and the Bermondsey Spa Gardens, all on the south side. These Gardens, now built over, were all alike. Every one of them had an ornamental water, walks and shrubs, a room for dancing and singing, and a stand for the band out of doors. People walked about, looked at each other, had supper, drank punch - and went home. If the Gardens were at any distance from the City they marched together for safety.

The river was still the favourite highway - thousands of boats plied up and down: it was much safer, shorter, and more pleasant to take oars from Westminster to the City than to walk or to hire a coach.

UNIFORM OF SAILORS ABOUT 1790

The high roads of the country were rapidly improving. Stage coaches ran from London to all the principal towns. They started, for the most part, at eight in the evening. They charged fourpence a mile, and they pretended to accomplish the journey at the rate of seven miles an hour. You may easily compare the cost of travelling when you remember that you may now go anywhere for a penny a mile - one fourth the former charge at five or six times the rate. The ‘short stages,’ of which there were a great many, ran to and from the suburbs: they were like the omnibuses, but not so frequent, and they cost a great deal more. Threepence a mile was the usual charge. There was a penny post in London, first set up by a private person. A letter sent from London cost twopence the first stage: threepence for two stages: above 150 miles, sixpence: Ireland and Scotland, sixpence: any foreign country a shilling. There were no bank notes under the value of 20l.: there were no postal orders or any conveniences of that kind. Money was remitted to London either by carrier or through some merchant. Banks there were by this time: but most people preferred keeping their own money in their own houses. Also banks being few everybody carried gold: this partly explains the prevalence of highway robbery: very likely the passengers on any long stage coach carried between them some hundreds of guineas: a whole railway train in these days would not yield so much: for people no longer carry with them more money than is wanted for the small expenditure of the day: tram, omnibus, cab, luncheon or dinner.

PART IV

So far we understand that London about the year 1750 was a city filled with dignified merchants all getting rich, and with a decorous, self-respecting population of retail traders, clerks, craftsmen, and servants of all kinds, a noisy but a well-behaved people. A church-going, sermon-loving, and orderly people.

This is in the main a fair and just appreciation of the City. But there is the other side which must not be overlooked - that side, namely, which presents the vice and sin and misery which always accompany the congregation of many people and the accumulation of wealth.

COSTUMES OF GENTLEFOLK, ABOUT 1784

The vice which has always been the father of most miseries is that of drink. In the middle of the last century, everybody drank too much. The dignity of the grave merchant was too often marred by indulgence in port and punch: the City clergy drank too much: even the ladies drank too much: it was hardly a reproach, in any class, to be overcome with liquor. As for the lower classes their habitual drink was beer - Franklin tells us that when he was a printer in London every man drank seven or eight pints of beer every day: nor was this small ale or porter: it was generally good strong beer: the beer would not perhaps hurt them so much - though the money spent on drink was enormous - but unfortunately they had now taken to gin as well - or instead. The drinking of gin at one time threatened, literally, to destroy the whole of the working classes of London. There were 10,000 houses - one in four - where gin was sold either secretly or openly. It was advertised that a man could get drunk for a penny and dead drunk for twopence. A check was placed upon this habit by imposing a tax of 5s. on every gallon of gin. This was in the year 1735 and in 1750 about 1,700 gin shops were closed. Since then the continual efforts made to stop the pernicious habit of dram drinking have greatly reduced the evil. But it was not only the drinking of gin: there was also the rum punch which formed so large a part in the life of the Georgian citizen. Every man had his club to which he resorted in the evening after the day’s work. Here he sat and for the most part drank what he called a sober glass: that is to say, he did not go home drunk, but he drank every night more than was good for him. The results were the transmission of gout and other disorders to his children. It should be, indeed, a most serious thing to reflect that in every evil habit we are bringing misery and suffering upon our children as well as ourselves. The habits of drinking showed themselves externally in a bloated body; puffed and red cheeks; a large and swollen nose; trembling hands; fat lips and bleared eyes: in the case of gin drinkers it showed itself in a face literally blue. It is said that King George the Third was persuaded to a temperate life - in a time of universal intemperance, this King remained always temperate - by the example of his uncle the Duke of Cumberland, who at the age of forty-five in consequence of his excesses in drink exhibited a body swollen and bloated and tortured with disease.

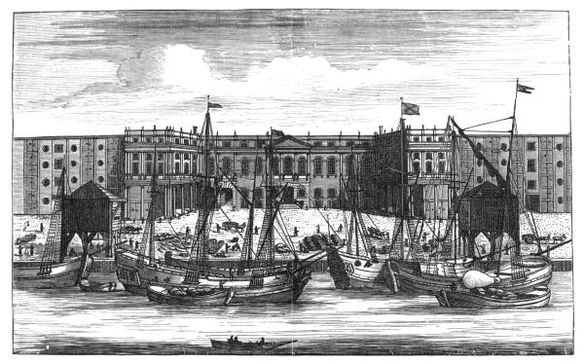

VESSELS UNLOADING AT THE CUSTOMS HOUSE, AT THE BEGINNING OF THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

If you look at a map of London of this time you will see that the city extended a long way up and down the river on either bank. Outside the walls there were the crowded districts of Whitechapel, Cripplegate, Bishopsgate, St. Katherine’s, Wapping, Ratcliff, Shadwell, Stepney, and others. These places were not only outside the wards and the jurisdiction of the City, but they were outside any government whatever. They were growing up in some parts without schools, churches, or any rule, order, or discipline whatever. The people in many of these quarters were of the working classes, but too often of the criminal class. They were rude and rough and ignorant to an extraordinary degree. How could they be anything else, living as they did? They were so unruly, they were so numerous, they were so ready to break out, that they became a danger to the very existence of Order and Government. They were kept in some kind of order by the greatest severity of punishment. They were hanged for what we now call light offences: they were kept half starved in foul and filthy prisons: and they were mercilessly flogged. In the army it was not unknown for a man to receive 500 lashes: in the navy they were always flogging the men. Horrible as it is to read of these punishments we must remember that the men who received them were brutal and dead to any other kind of persuasion. Drink and ignorance and habitual vice had killed the sense of shame and stilled the voice of conscience. The only thing they would feel was the pain of the whip.

PART V

It was estimated, some years later than the period we are considering, that there were then in London 3,000 receivers of stolen goods; that is to say, people who bought without question whatever was brought to them for sale: that the value of the goods stolen every year from the ships lying in the river - there were then no great Docks and the lading and unlading were carried on by lighters and barges - amounted to half a million sterling every year: that the value of the property annually stolen in and about London amounted to 700,000l.: and that goods worth half a million at least were annually stolen from His Majesty’s stores, dockyards, ships of war, &c. The moral principle, a writer states plainly, ‘is totally destroyed among a vast body of the lower ranks of the people.’ To meet this deplorable condition of things there were forty-eight different offences punishable by death: among them was shoplifting above five shillings: stealing linen from a bleaching ground: cutting hop bines and sending threatening letters. There were nineteen kinds of offences for which transportation, imprisonment, whipping, or pillory were provided: there were twenty-one kinds of offences punishable by whipping, pillory, fine and imprisonment. Among the last were ‘combinations and conspiracies for raising the price of wages.’ The classification seems to have been done at haphazard: for instance, to embezzle naval stores would seem as bad as to steal a master’s goods: but the latter offence was capital and the former not. Again, it is surely a most abominable crime to set fire to a house, yet this is classed among the lighter offences. It was therefore a time when there was a large and constantly increasing criminal class: and, as a natural cause or a natural consequence, whichever we please, there was a very large class of people as ignorant, as rude, and as dangerous as could well be imagined. I do not think there was ever a time, not even in the most remote ages, when London contained savages more brutal and more ignorant than could be found in certain districts outside the City of the Second George. But these poor wretches had one great virtue - they were brave: they manned our ships for us and gave Britannia the command of the sea: they were knocked down, driven and dragged aboard the ships by the press-gang. Once there they fell into rank and order, carried a valiant pike, manned the guns with zeal, joined the boarding party with alacrity and carried their cutlasses into the forlorn hope with faces that showed no fear. They were so strong, so stubborn, and so brave, that one sighs to think of the lash that kept them in discipline and order. There is one more side of London that must not be forgotten. It was a great and prosperous city: we can never dwell too strongly on the prosperity of the city: but there were shipwrecks many and disastrous. And the fate of the man who could not pay his debts was well known to all and could be witnessed every day, as an example and a warning. For he went to prison and in prison he stopped. ‘Pay what you owe,’ they said to the debtor, ‘or else stay where you are.’ The debtor could not pay: in prison the debtor had no means of making any money: therefore he stayed where he was until he died. For the accommodation of these unhappy persons there were the King’s Bench and the Marshalsea, both in Southwark: there were the two Compters, both in the City: and there was the Fleet Prison.

The life in these prisons can be found described in many novels. It was a squalid and miserable life among ruined gamblers, spendthrifts, profligates, broken down merchants, bankrupt tradesmen, and helpless women of all classes. Unless one had allowances from friends, starvation might be the end. In one at least the common hall had shelves ranged round the walls for the reception of beds: everything was carried on in the same room, living, sleeping, eating, cooking. And into such a place as this the unhappy debtor was thrust, there to remain till death released him.

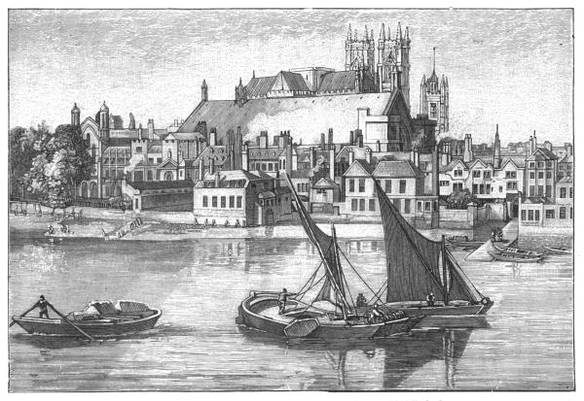

THE OLD HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT AND WESTMINSTER ABBEY, 1803

This was the London of a hundred and fifty years ago. No longer picturesque as in the old days, but solidly constructed, handsome, and substantial. The merchants still lived in the city but the nobles had all gone. The Companies possessed the greater part of the City and still ruled though they no longer dictated the wages, hours, and prices. Within the walls there reigned comparative order: outside there was no government at all. The river below the Bridge was crowded with ships moored two and four together side by side with an open way in the middle. Thousands of barges and lighters were engaged upon the cargoes: every day the church bells rang for a large and orderly congregation: every day arose in every street such an uproar as we cannot even imagine: yet there were quiet spots in the City with shady gardens where one could sit at peace: wealth grew fast: but with it there grew up the mob with the fear of anarchy and license, a taste of which was afforded by the Gordon Riots. Yet it would be eighty years before the city should understand the necessity for a police.

The Government of the City

PART I

Let us walk into the streets. You will not observe, because you are used to these things, and have been brought up among them, and are accustomed to them, that all the men go about unarmed: that they do not carry even a stick for their protection: that they do not fight or quarrel with each other: that the strong do not knock down the weak but patiently wait for them and make room for them: that ladies walk about with no protection or escort: that things are exposed for sale with no other guard than a boy or a girl: that most valuable articles are hung up behind a thin pane of glass. You will further observe men in blue - you call them policemen - who stroll about in a leisurely manner looking on and taking no part in the bustle. What do these policemen do? In the roads the vehicles do not run into one another, but follow in rank and order, those going one way taking their own side. Everybody is orderly. Everything is arranged and disposed as if there was no such thing as violence, crime, or disorder. You think it has always been so? Nay: order in human affairs does not grow of its own accord. Disorder, if you please, grows like the weeds of the hedge side - but not order.

Again, you always find the shops well provided and filled with goods. There are the food shops - those which offer meat, bread, fruit, vegetables, coffee, tea, sugar, butter, cheese. These shops are always full of these things. There is never a day in the whole year when the supply runs short. You think all these things come of their own accord? Not so: they come because their growth, importation, carriage, and distribution are so ordered by experience that has accumulated for centuries that there shall be no failure in the supply.

Again, you find every kind of business and occupation carried on without hindrance. Nobody prevents a man from working at his trade; or from selling what he has made. One workman does not molest another though he is a rival. You think, perhaps, that this peacefulness has come by chance? Nay: strife comes to men left without rule - but not peace.

You may observe further, that the streets are paved with broad stones convenient for walking and easy to be kept clean: that the roadways are asphalted or paved with wood, and are also clean: things that must be thrown away are not thrown into the streets: they are collected in carts and carried away. You think that the streets of cities are kept clean by the rain? Not so: if we had only the rain as a scavenger we should be in a sorry plight.

You find that water is laid on in every house. How does that water come? That gas lights up houses and streets. How does the gas come? That drains carry off the rain and the liquid refuse. How did the drains come?

You may see as you go along a man who walks from house to house delivering letters. Does he do this of his own accord? You know very well that he does not; that he is paid to do it: that he does his duty. What is the whole of his duty? Who gives him his orders?

Or you may see another man going from house to house leaving a paper at each. He is a rate collector. What is a rate collector? Who gives him authority to take money from people? What does he do with the money?

Or you may see placards on the walls asking people to vote for this man, or for that man, for the School Board, the County Council, the House of Commons, or the Vestry. Why does this man want to get elected to one of those Councils? What will he do when he is elected? What are all these Councils for?

Again, the thing has never been otherwise in your recollection and you therefore do not observe it, but if you listen you will find that men talk with the greatest freedom as they walk with their friends: no one interferes with their conversation, no one interferes with their dress, no one asks them what they want or where they are going. Did this personal freedom always exist? Certainly not, for personal freedom does not grow of its own accord.

You will also observe, as you walk along, churches - in every street, a church - of all denominations: you will find posted on the walls notices of public meetings for discussion or for lectures and addresses on every conceivable topic: you will see boys crying newspapers in which all subjects are treated with the utmost freedom. You suppose, perhaps, that freedom of thought, of speech, of discussion, of writing comes to a community like the rain and the wind? Not so. Slavery comes to a community if you please, but not freedom. That has to be achieved.

You have seen the city growing larger and wealthier: the people getting into finer houses, wider streets, and more settled ways. Now, there is a thing which goes with the advance of a people: it is good government. Unless with advance of wealth there comes improved government, the people fall into decay. But, which is a remarkable thing, good government can only continue or advance as the people themselves advance in wisdom as well as in wealth. Such government as we have now would have been useless in the time of King Ethelred or King Edward I. Such government as we have now would be impossible had not the citizens of London continued to learn the lessons in order, in good laws, in respect to law, which for generation after generation were submitted to the people.

PART II

Since all these things do not grow of their own accord, by whom were they first introduced, planted, and developed? By whom are they now maintained? By the collection of powers and authorities which we call the Government of the City and County of London.

Thus order reigns in the streets: in the rare cases where disorder breaks out the policeman is present to stop it. His presence stops it. Not because he is a strong man, but because he is irresistible: he is the servant of the Law: he represents Authority. Formerly the Alderman of the Ward walked about his own streets followed by two bailiffs. If any one dared to resist the Alderman he was liable to have his hand struck off by an axe. In this way people were taught to respect the Law. By such sharp lessons it was forced upon them that the Law must be obeyed. Thus there gradually grew up among them a desire for Order. The policeman appointed by the Chief Police Officer stands for a symbol and reminder of the Law.

You have seen how the people of London had their Folks’ Mote, their Ward Mote, and their Hustings. From the first of these has sprung the Common Council, which rules over the City of London within the old boundaries. The Folks’ Mote was a Parliament of the People - a rude and tumultuous assembly, no doubt, but a free assembly. When the City grew great such a Parliament became impossible. It therefore became an elective Parliament. The election was - and is still - conducted at the Ward Motes, each Ward returning so many members in proportion to its population, for the Common Council. The Councillors are elected for one year only. If there is a vacancy an Alderman is also elected, but that is for life.

Formerly every man in London followed a trade: he therefore belonged to a Company. And as the commonalty, all the men of London together assembled, i.e. all the members of all the companies, elected the Mayor, so to this day the electors of the Lord Mayor are the members of the Companies. None others have any voice in the election. The Companies no longer include all the citizens, and the craftsmen have nearly all left the City. But the power remains.

The Lord Mayor is the chief magistrate. With him is the Court of Aldermen, also magistrates. He has with him the great officers of the City: the Recorder, or Chief Justice; the Town Clerk; the Chamberlain, who is the Treasurer; the Remembrancer; and the Common Sergeant.

The education of the young, the maintenance of the old, the paving and cleansing of the streets, the lighting, the removal of waste, the engines for extinguishing fires, the regulation of the road traffic, the preservation of order, all these things are conducted by the various Councils and Courts of the City, and the cost is provided by that kind of taxation known as the rates. That is to say, every house is ‘rated’ or estimated as worth so much rent. The tenant who pays the rent has to pay, in addition, a charge of so much in the pound for this and that object. Thus for education, if the rate be 1s. in the pound, a man in a house whose rent is 100l. has to pay 5l. on that charge. He has to pay also for the Police, the Fire Brigade, the Poor, lighting and paving. His own water supply is managed by a private company, and another private company gives him his gas or his electricity. In the same way the food is provided by private persons and brought to the city by private companies. Thus you are governed by men whom you are supposed yourselves to elect: order is kept for you: education, protection, and conveniences are found for you: in a word, life is made tolerable for you by your own Government - elected by yourselves - and at your own cost.

PART III

That is the best Government which gives the greatest possible liberty to its people: only that people can be happy which is capable of using their freedom aright. You have seen how your personal freedom from violence, robbery, and molestation in your work is secured for you: how you are enabled to live in comfort and cleanliness - by a vast machinery of Government whose growth has been gradual and which must always be ready to meet changes so as to suit the needs of the people. One point you must carefully remember, that your greatest liberty is liberty of speech and of thought and of the Press. It is not so very long since martyrs - Catholic as well as Protestant - were executed for their religious belief: Catholics and Jews until quite recently were excluded from Parliament. A hundred years ago the debates of Parliament could not be reported: one had to weigh his words very carefully in speaking of the Sovereign or the Ministers: certain forms of opinion were not allowed to be published. All that is altered. You can believe what you like and advocate what you like, so long as it is not against Divine Law or the Law of the Land. Thus, if one were to preach the duty of Murder he would be very properly stopped. Therefore, when you buy a daily paper: whenever you enter a church or chapel: whenever you hear an address or a lecture remember that you are enjoying the freedom won for you by the obstinacy and the tenacity of your ancestors.

We have spoken of the City Companies. They still exist and though their former powers are gone and they no longer control the trades after which they are named, their power is still very great on account of the revenues which they possess and their administration of charities, institutions, &c., under their care. There were 109 in all, but many have been dissolved. There are still, however, 76. About half of these possess Halls which are now the Great Houses of the City. The number of livery men, i.e. members of the Companies, is 8,765. The Companies vary greatly in numbers: there are 448 Haberdashers, for instance: 380 Fishmongers: and 356 Spectacle Makers: while there are only 16 Fletchers, i.e. makers of arrows. Many of the trades are now extinct, such as the Fletchers above named, the Bowyers, the Girdlers, the Bowstring Makers and the Armourers.

Some of these Companies are now very rich. One of them possesses an income, including Trust money, of 83,000l. a year. It must be acknowledged that the Companies carry on a great deal of good work with their money. Many of them, however, have little or nothing: the Basket Makers have only 102l. a year: the Glass Sellers only 21l. a year: the Tinplate Workers 7l. 7s. a year. If, therefore, you hear of the great riches of the City Companies remember (1) that 25 of them have less than 500l. a year each: and (2) that the rich Companies support Technical Colleges and Schools, grant scholarships, encourage trade, hold exhibitions, maintain almshouses, and make large grants to objects worthy of support. It is not likely that the privilege of electing the Lord Mayor will long continue to be in the hands of the Companies. It is not, indeed, worthy of a great City that its Chief Magistrate should be elected by so small a minority as 8,765 out of the hundreds of thousands who have their offices and transact their business in the City: but while this privilege will cease, the Companies may remain and continue to exercise a central influence, at the least in London, over the Crafts and Arts which they represent. Let us never destroy what has been useful: let us, on the other hand, preserve it, altered to meet changed circumstances. For an institution is not like a tree which grows and decays. If it is a good institution, built upon the needs and adapted to the circumstances of human nature, it will never decay but, like the Saxon form of popular election, live and develop and change as the people themselves change from age to age.

Greater London

It has been a great misfortune for London that, when its Wall ceased to be the true boundary of the town, and when the people began to spread in all directions outside the walls, no statesman arose with vision clear enough to perceive that the old system must be enlarged or abolished: that the City must cease to mean the City of the Edwards, and must include these new suburbs, from Richmond on the West to Poplar on the East, and from Hampstead on the North to Balham on the South. It is true that something was done: there are the Wards of Bridge Without, which is Southwark: and of Farringdon Without. There should have been provision for the creation of new Wards whenever the growth of a suburb warranted its addition. That, however, has not been done. The Old London remains as it was, and as we now see it, surrounded by another, and an immense City, or aggregate of cities, all placed under the rule of a Council.

This was done by the Act of 1888, which created a County whose boundaries were the same as those of the former Metropolitan Board of Works; in other words, it embraces all the suburbs of London properly so called. This County extends from Putney and Hammersmith on the West to Plumstead on the East: on the North are Hampstead and Highgate; on the South are Tooting, Streatham, Lewisham and Eltham. There are 138 Councillors, of whom 19 are Aldermen and one a Chairman. The conservative tendency of our people is shown in their retention of the old division of aldermen. It is, once more, Kings, Lords, and Commons. But the functions of the Aldermen do not differ from those of the Councillor. The Councillors are elected by the ratepayers for three years, the Aldermen for six; but there is a rule as to retiring by rotation.

The powers of the County Council are enormous. It regulates the building of houses and streets: the drainage: places of amusement: it can close streets and pull down houses: it administers and makes regulations concerning parks, bridges, tunnels, subways, dairies, cattle diseases, explosives, lunatic asylums, reformatory schools, weights and measures. It grants licenses for music and dancing: it carries on, in fact, the whole administration of the greatest City in the world, and, in some respects, the best managed City.

In order to carry out these works the Council expend about 600,000l. a year. It has a debt of 30,000,000l., against which are various assets, so that the real debt is no more than 18,000,000l. The rating outside the City was last year 12½d. in the pound. The first Chairman was Lord Rosebery. He has been succeeded by Sir John Lubbock and Mr. John Hutton. The list of County Councillors contains men of every rank and every opinion. Dukes, Earls and Barons, sit upon the Council beside plain working men - an excellent promise for the future.

Such is the government of London. Within the City what was intended to be democratic has become oligarchic. The election by the whole people has become the election by 8,000 only. Without the City a great democratic Parliament attracts men whose historic names and titles belong to the aristocracy. In the London County Council the Peers may, if they are elected, sit beside the Commons.

Lastly, what is the chief lesson for you to learn out of this history? It is short, and may be summed up in a few sentences.

1. Consider how your liberties have grown silently and steadily out of the original free institutions of your Saxon ancestors. They have grown as the trunk, the tree, the leaves, the flower, the fruit, grow from the single seed. The Folk Mote, the ‘Law worthiness’ of every man, the absence of any Over Lord but the King, have kept London always free and ready for every expansion of her liberties. Respect, therefore, the ancient things which have made the City - and the country - what it is. Trust that the further natural growth of the old tree - still vigorous - will be safer for us than to cut it down and plant a sapling, which may prove a poison tree. And with the old institutions respect the old places. Never, if you can help it, suffer an old monument to be pulled down and destroyed. Keep before your eyes the things which remind you of the past. When you look on London Stone, remember that Henry of London Stone was one of the first Mayors. When you go up College Hill, remember Whittington who gave it that name. When you pass the Royal Exchange think of Gresham: when you go up Walbrook remember the stream beneath your feet, the Roman Fortress on your right, and the British town on your left. London is crammed full of associations for those who read and know and think. You will be better citizens of the present for knowing about the citizens of the past.

2. The next lesson is your duty to your country. What does it mean, the right of the Folk Mote? The Mote has now become a House of Commons, a County Council, a School Board. You have the same rights that your ancestor had. He was jealous over them: he fought to the death to preserve them and to strengthen them. Be as jealous, for they are far more important to you than ever they were to him. You have a hundred times as much to defend: you have dangers which he did not know or fear. Show your jealousy by exercising your right as the most sacred duty you have to fulfil. Your vote is an inheritance and a trust. You have inherited it direct from the Angles and the Jutes: as you exercise that vote so it will be ill or well with you and your children. Be very jealous of the man you put in power: learn to distinguish the man who wants place from the man who wants justice: vote only for the right man: and do your best to find out the right man. It is difficult at all times. You may make it less difficult by sending to the various Parliaments of the country a man you know, who has lived among you, whose life, whose private character, whose previous record you know instead of the stranger who comes to court your vote. Above all things vote always and let the first duty in your mind always be to protect your rights and your liberties.

These are the two lessons that this book should teach you - the respect that is due to the past and the duty that is owed to the present.