The “Advantages” of Intersectionality

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

—WALT WHITMAN, “SONG OF MYSELF”

Nearly three decades ago, Peggy McIntosh’s classic 1988 essay on White privilege captured the imagination of progressives worldwide and has served as a foundational piece for diversity and inclusion education ever since. Among the essay’s most captivating portions is an inventory of how White privilege is manifested, providing specific examples of the ways in which White individuals reap racial privilege’s benefits, ways they are often unaware of.bb

Following McIntosh’s example, other lists have sprouted up surrounding a particular identity and the privilege it brings with it. By drawing attention to the privileges surrounding ability, wealth, sexual orientation, class, gender, gender identity, and religion, these enumerations have proven efficient and effective ways to educate readers with specific examples of how privilege operates.

At the same time that these privilege lists have proliferated, scholars have elaborated on privilege and pursued the ongoing development of privilege and related studies. Among these developments have been explorations of intersectionality, a term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw referring to the ways in which a person’s various identities interact and their combined impact on lived experiences (1989). Much of the literature in this area has focused on the compounding negative impact of marginalized identities, with the experiences of Black women providing one such example (Crenshaw, 1991).

While the privilege inventories mentioned above provide excellent examples of privilege along a variety of single axes, few address intersectionality or more than one identity at a time.cc This could be because much of the literature on intersectionality focuses on two or more marginalized identities and how those identities interact to magnify oppression, or because of the inherent difficulty of disentangling two specific threads of identity from the elaborate, complicated tapestry that makes up a human being. Regardless, as more privilege conversations include intersectionality as a vehicle for understanding and educating (Ferber), the classic McIntosh-style list format has the potential to be a helpful tool for individuals exploring a variety of intersecting identities.

While I carry a number of privileged identities (e.g., White, male, cisgender), I also have (at least) two non-privileged identities: I identify religiously and visibly as Jewish, and I am openly gay. Individually, each of these independently marks me for exclusion in society as a whole, as numerous researchers have pointed out, and on a regular basis, I run into the ill effects of either straight privilege, religious privilege, or both.

My experiences as an openly gay Jew generally affirm the negative synergies often associated with the intersectionality of two marginalized identities. Religious privilege flows through the queer community, just as it does the rest of society, presenting expected challenges in being Jewish rather than Christian (at least culturally Christian) in queer contexts. Similarly, Jewish settings are not free from heteronormativity and sexual orientation privilege, and it is easier to be a straight Jew than a gay one. Several studies have highlighted the collision of these two identities and the difficulties faced by gay and lesbian Jews in integrating these two aspects of who they are (Abes, 2011; Schnoor, 2006), as well as the lower rates of practice and engagement for lesbian, gay, and bisexual Jews when compared to the Jewish community as a whole (Cohen, 2009).

That said, the intersectional effect of being both gay and Jewish is, oddly enough, not entirely disadvantaging, when compared to the experience of those who are gay and not Jewish. Having had repeated conversations with gay non-Jews, I am struck by the way in which I enjoy certain unearned benefits that they do not, based on my being Jewish. It is almost as if my Jewish identity, and the resources that flow from it, grant me entrance to a queer-friendly (or at least a queer-friendlier) sanctuary from some of the heteronormativity and homophobia in the world at large.

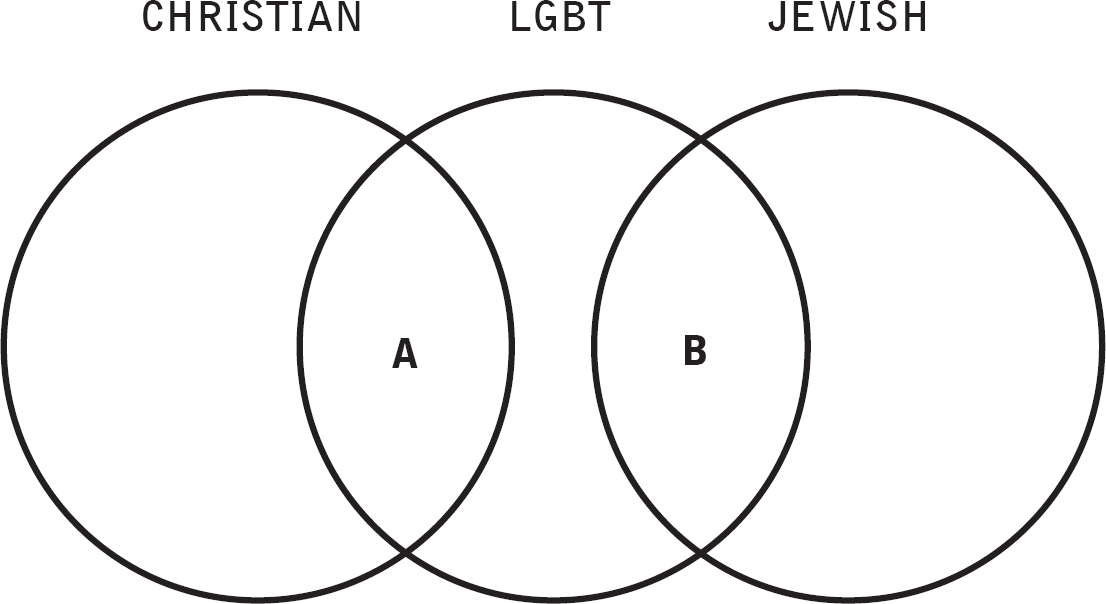

For those more visually inclined among us, the following figure may be useful:dd

In essence, my experience as a resident of Area B is, in some ways, more advantaged than that of Area A dwellers. Because those in Area A carry religious privilege that I do not, this seems counterintuitive. Nevertheless, examples of my Jewish identity giving me support unavailable to LGBT Christians are surprisingly numerous.

Increasingly mindful of these benefits and inspired like so many others by Peggy McIntosh, I have put together a list of specific things that I, as a gay Jew, take for granted and that gay non-Jews are less likely to have. Some are particular to my being gay and Jewish, while others apply more generally to LGBT or queer Jews. The items listed are not exclusively or universally Jewish; there are others who reap similar benefits, such as gay Unitarian-Universalists or LGBT individuals who affiliate with the Metropolitan Community Church or United Church of Christ,ee and the advantages I have included are uneven in their spread through the Jewish world, particularly pronounced in certain settings and nearly absent in others.ff Even so, what strikes me as unusual is their widespread, visible, mainstream and at times even dominant nature in the Jewish community as a whole, in a way I have not seen in Christianity writ large or almost any other overarching religion.

This list is not without caveats. Although I have done my best to isolate these two identities and how they interrelate, I am certain that other aspects of who I am have seeped in. Moreover, to be clear, this is not a “privilege list” along the lines of those enumerated elsewhere, and does not obviate the need to confront systemic oppression; it is difficult to see how a gay Jew could be “privileged” based on those identities in the way that men, straight people, White people or other holders of dominant identities are. This is, rather, an exploration of my own intersectionality, the gay-Jewish perks I often forget are not universal and the unexpected ways in which two salient, marginalized aspects of who I am interact.

With that introduction, the following is a list of benefits that I enjoy as a gay Jewish man and that are largely unavailable to gay non-Jews:

1. Should I marry someone of the same gender, there is religious liturgy readily available for me to use, either verbatim or as a starting point for designing my own liturgy, and there are abundant clergy of my religion willing to officiate at same-gender wedding ceremonies.

2. Numerous institutions, agencies, places of worship and community organizations affiliated with my religion have workplace protections based on sexual orientation and gender expression or identity.

3. Multiple denominations or movements within my religion have taken progressive stances on issues related to sexual orientation and gender identity, and historically have demonstrated support for marriage equality and legal protections for LGBT individuals.

4. My religion has numerous queer-inclusive rituals, including rituals for coming out, transitioning, assisted reproduction and same-gender divorce, available for use and widely disseminated, and has been using them for a significant stretch of time.

5. Mainstream organizations and conferences for my religious group offer programs and sessions that present and have professionals who speak to LGBT issues in a positive way.

6. Those who identify with my religion often experience marginalization and oppression or are exposed to the history of past oppressions, providing ready narratives for non-LGBT coreligionists to connect and empathize with my experience as an LGBT individual.

7. There are numerous lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and allied clergy I can turn to for pastoral counseling, spiritual guidance and other forms of religious and spiritual support.

8. If I choose to become a clergyperson or lay leader in my religious community, I would have several options to select from in pursuing my goals, and being lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender would not be an inherent obstacle to pursuing any of them.

9. Among the sacred texts of my religion are stories, narratives and directives that easily lend themselves to supporting queer perspectives and inclusive stances.

10. In public surveys, my religious community demonstrates comparatively strong support for issues of importance to the queer community.

11. In filling out forms to join most religious organizations, it is unlikely that I will have to modify the membership form to make it fit me and my family.

12. There are numerous organizations and gatherings that focus on my religion specifically and its intersections with LGBT identities.

13. When celebrating anniversaries and other relationship milestones, I can find a religious community that will honor them.

14. Dating websites that cater to people of my religion are likely to have searches for same-sex partners as an option.

15. There are numerous books, websites, studies and other resources that respond to the intersectionality of my religion and LGBT identity in a positive way.

16. My experience with religious privilege, marginalization and oppression prepared me and gave me skills to respond to heteronormativity and straight privilege.

17. In looking nationally and internationally, I can see LGBT role models who share my religious identity in public life, including politics, academics and the arts with little effort.

18. In seeking out a mentor my religious community, I am able to find someone with a sexual orientation or gender identity identical to my own.

19. People’s general unfamiliarity with my religion makes it less likely that they will sense or point out any perceived conflict between me being religious and me being openly queer.

20. If my partner of the same gender passed away, a significant portion of adherents and leaders would accord me the appropriate respect due a mourner in my position.

All told, this presents what could be read as a contradiction: when taken together, two marginalized and oppressed aspects of who I am create benefits that holders of only one of those identities are less likely to carry. It is almost as if these two “negative” identities (insofar as they are both marginal) produce something of a positive result, an outcome that holds in mathematics, but a phenomenon that feels somewhat contradictory in speaking of privilege.

The effects of intersectionality, especially as they reflect privilege and marginalization, are nuanced and subtle, and the fast-changing pace of LGBT acceptance in religious settings requires us to be especially attentive of how these combinations play out. As we become increasingly aware of the benefits of an intersectionality-based approach to identity, power, and privilege education, it would not surprise me if the contradictions multiply because surely, to paraphrase Walt Whitman, each of us carries contradictions and contains multitudes.

references

Abes, E. S. (2011). Exploring the Relationship between Sexual Orientation and Religious Identities for Jewish Lesbian College Students. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 15(2), 205–225.

Cohen, S. M., Aviv, C., & Kelman, A. Y. (2009). Gay, Jewish, or both: Sexual orientation and Jewish engagement. Journal of Jewish Communal Service, 84(1/2), 154–166.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 139.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 1241–1299.

Coyle, A., & Rafalin, D. (2001). Jewish gay men’s accounts of negotiating cultural, religious, and sexual identity: A qualitative study. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 12(4), 21–48.

Ferber, A. and O’Reilly Herrera, A. “Privilege as Key in the Pedagogy of Intersectionality.” Unpublished.

McIntosh, P. (1988). White privilege: Unpacking the invisible knapsack. Race, Class, and Gender in the United States: An Integrated Study, 4, 165–169.

Rapoport, C. (2004). Judaism and homosexuality: An authentic Orthodox view. Mitchell Vallentine & Company.

Schnoor, R. F. (2006). Being gay and Jewish: Negotiating intersecting identities. Sociology of Religion, 67(1), 43–60.

![]()

a Goren, Seth. “Gay and Jewish: The ‘Advantages’ of Intersectionality.” Copyright 2015 by Seth Goren. Reprinted by permission of the author.

b Among McIntosh’s examples are one’s race being an asset in social and professional situations, having positive educational curricula and media coverage of one’s race, and not being taken as a representative of one’s race.

c The one example of an intersectional list I was able to find is “The Black Male Privileges Checklist” (available at http://jewelwoods.com/node/9), which focuses on the privileges enjoyed by Black men, and the acute marginalization of Black women.

d This figure makes Jewish and Christian religious identities mutually exclusive. While there may be some overlap in Christian religious identities with Jewish ethnic identities, Jewish and Christian religious identities are typically thought of in the mainstream Jewish community as incompatible.

e There certainly are LGBT-welcoming Christian denominations, and LGBT persons in those denominations would “score” relatively highly on this inventory. That said, even in this time of substantial flux on queer issues in the North American religious world, most Christian movements and organizations at best continue to struggle with LGBT issues, limiting opportunities for inclusion and contributing to a perception of Christianity, on the whole, as unwelcoming.

f Many of these benefits accrue in a most pronounced manner in larger metropolitan areas and in pluralistic Jewish or non-Orthodox Jewish organizations and places of worship. That said, I have often been surprised at the way in which these benefits accumulate even in less densely populated areas and in the Orthodox Jewish world (e.g., Rapoport, 2004).