John Brown worked not simply for black men—he worked with them; and he was a companion of their daily life, knew their faults and virtues, and felt, as few white Americans have felt, the bitter tragedy of their lot.

—W. E. B. DU BOIS

With these words, W. E. B. Du Bois opened his biography of John Brown, the white abolitionist who led an armed assault against slavery. Brown had a religiously inspired moral vision of an America freed of the sin of slavery. As Du Bois indicated, Brown identified closely with African Americans, saw their cause as a common one, and deeply believed that he was working in the best interests of both blacks and whites. Brown certainly had fire in his heart. In the words of Reverend Joseph Lowery, referenced in the subtitle of this book, Brown came to deeply embrace the cause of racial justice. So do many white activists who work for racial justice today. How did they come to do so? . . .

How can white Americans come to care enough about racism that they move from passivity to action for racial justice? I decided to look for clues to answer that question by examining the lives and self-understanding of white people who have made that move and became committed activists for racial justice. . . .

Head, Heart, and Hand

Americans place great faith in education as a force for social change. If whites knew about racism, so this thinking goes, and understood that it continues to exist and oppress people of color, they would come to oppose it. I did find that awareness of racism proves important to the development of commitment on the part of the interviewees, but only partly so. Rather, I found that the activists in this study came to support racial justice through a combination of cognitive and emotional processes at the heart of which lay moral concerns.

Activists begin their journey to racial justice activism through a direct experience that leads to an awareness of racism, but the real action does not lie in the knowledge gained. What makes this experience a seminal one for them is that through it they recognize a contradiction between the values with which they have grown up and the reality of racial injustice. When they confront this value conflict, activists express anger at racial injustice. They care about racism at first because they believe deeply in the values that are being violated. They express what I call a moral impulse to act.

If we stop here, however, we are left with the do-gooder, the white person who helps people of color but remains at a distance. I find that relationships with people of color begin to undermine that separation. Whites learn more deeply about the reality of racism through these relationships. But more than the head is involved here, too. Personal relationships and stories tug at the heart; that is, they create emotional bonds of caring. Whites become concerned about racism because it affects real people they know. Rather than working for people of color, they begin to work with them, their commitment nurtured by an ethic of care and a growing sense of shared fate.

As whites take action for racial justice, they build more than individual relationships with people of color. Working collectively in activist groups, they prefigure the kind of human relationships they hope will characterize a future America. In other words, as they attempt to create respectful collaborative relationships, they construct a more concrete sense of the kind of society for which they are working, what I call a moral vision. They find purpose and meaning in a life that works for the kind of society they want for themselves, their children, and all people across racial lines. Some refer to this as a calling, but they all begin to express a direct interest for themselves in a life committed to racial justice activism. Activists come to see that racism harms whites, as well as people of color. It denies whites their full humanity and blocks progress toward a society that would benefit everyone, one that would be in the interest of whites, as well as people of color. Forging community in multiracial groups deepens a sense of shared fate and bonds of caring as it fosters hope for the possibilities of social change. If the moral impulse represents what activists are against, an emerging moral vision represents what they are for, a truly human or beloved community. It provides a foundation for shared identities as multiracial political activists.

Activists develop commitment and deepen their motivations over time, in part through their experiences taking action against racism. Activism provides whites an opportunity to build relationships with people of color, as well as other white activists, and to construct the kind of multiracial community in which they develop and implement a vision of a future society. This is not a linear process but rather a cycle or perhaps a spiral. Indeed, a model of motivation leading to action is too simplistic. Rather, I find that activists develop commitment over time and through activism. Indeed, there may be setbacks or a need for constant vigilance as the pressures of the dominant society constantly push whites back toward a white world and worldview.

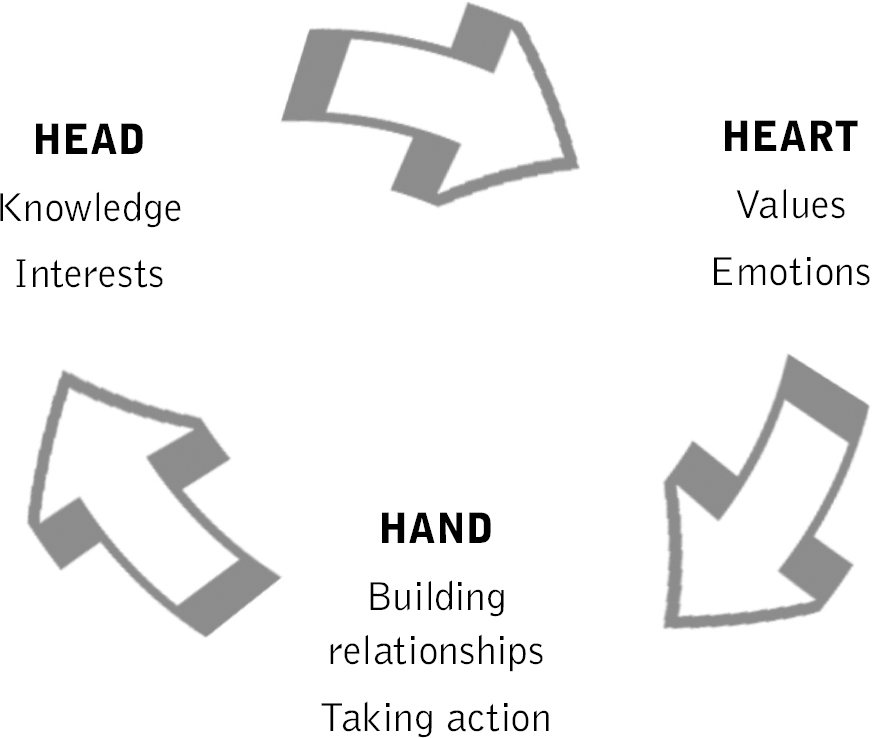

For the sake of clarity, I have presented the processes in an ordered form, starting with a moral impulse and leading to a moral vision. To some extent, this order is represented in the activists’ lives. However, some activists inherit a sense of a moral vision from their families or their religious traditions and so have elements of a vision at the beginning. For others, relationships come earlier rather than later. Meanwhile, activists continue to express moral outrage even after they deepen their commitment through relationships and construct a moral vision. Each of these processes has its own particular effects on developing commitment. Yet each represents a piece of the larger puzzle of commitment. I have illustrated [on p. 80] how they work together to forge a deep commitment to racial justice on the part of white activists (Figure 25.1).

It may be useful to summarize the relationship between these processes by visualizing them as a cycle. If we start with the heart, anger at the violation of deeply held values leads some white activists to take action for racial justice and thereby build relationships with people of color. These connections create knowledge about the experiences of people of color and begin to shape a sense of common interests. By working in emergent multiracial communities, white activists develop caring and hope while generating a moral vision of a multiracial society with justice at its center. They continue to experiment with building respectful, collaborative associations in multiracial activist groups, all the while developing a sense of their personal interest in racial justice as they find that activism offers a meaningful life.

Figure 25.1

Within the context of the interactive approach just elaborated, I found moral concerns to play a key role in the development of commitment and action. This approach lies in stark contrast to most thinking on racial justice, which focuses on the cognitive domain. As noted earlier, we place great emphasis on educating white Americans about racism. Certainly, one must understand that racism is an important problem if one is to take action against it. In that sense I did find the processes of learning about the history and experiences of people of color and of developing a racial justice framework to be important to the activists in this study. Moreover, cognitive knowledge about racism, including research and analysis of how it works, is necessary to know what to do about it. However, by itself, knowledge does not motivate one to take action. It answers the “what” to do but not the “why” to do it.

Motivation comes primarily from a moral source even as its character develops from impulse to care and vision. White activists start with a moral impulse that racism is wrong because certain values they care about are being violated. Through relationships they deepen their commitment as they develop an ethic of caring. The many children of color who drop out of high school are no longer just numbers but rather real people to whom they are connected. Eventually activists make the cause their own through the construction of a moral vision of a just, multiracial, and human community.

The other way in which cognitive processes are typically emphasized is through a focus on the rational calculation of self-interest. If whites can come to see their common material interests with people of color (in better health care, for example), then they are likely to find common cause with people of color. Or if whites can see that it will cost them less to educate children than to incarcerate them after they drop out of high school and get into trouble, then they will likely support a more just educational system. These are important arguments. Yet I found almost no evidence that rational, interest-based understandings like these motivated the activists in my study.

I do not want to counterpose morality and interests. Rather, what I discovered is that activists find a way to get them to work together and to reinforce each other. In particular, as white activists construct a moral vision of a future society based upon their values, they develop a way to understand white interest in racial justice. As we have seen, these visions encompass material concerns. Activists are working today to address poverty, rebuild communities, and create better educational systems. The future society they envision would offer more equitable social provision for people of color and for most whites as well. Yet it would perhaps more fundamentally be a community based upon what activists see as deeply human values, where people treat each other with respect and caring across lines of race. Out of these values, better material provision can emerge. While interests and morality work together, in the end, activists embed an understanding of white people’s interests into their vision of human community, and that is why I argue that moral sources are primary.

Pursuing a moral vision does not mean working altruistically for people of color. The activists in this study have developed a clear sense of their own direct stake in racial justice. In order to understand how morality and interests can work together at the individual level, we have to break from the notion that equates moral action with altruism—doing for someone else rather than for yourself. Nathan Teske, in his study of political activists, has criticized the duality of self-interested versus altruistic action. He shows instead that when activists uphold their most deeply held values by working for the common good, they are also benefiting themselves in ways that are quite rational. They construct an identity for themselves as moral persons, which allows them to gain a meaningful life and a place in history.

Teske reconciles morality and self-interest at the individual level, but I also found that activists resolve the dichotomy at the collective level, too, by embedding an understanding of the collective interests of white Americans in a moral vision. The two levels are in fact related. Activists derive meaning in their lives by pursuing that vision. As activist Roxane Auer captured it, “I’m contributing to the world I want to live in.” In other words, activists develop a strong and direct interest in living their lives in the present in accordance with the principles on which that beloved community would be founded. Indeed, along with other activists they attempt to work out those principles by implementing them in the present.

It is also a mistake to counterpose cognitive understanding and emotions. Traditionally, we have understood emotionally based activity as nonrational and suspect in politics. Yet there is a large and growing literature in several fields that shows that emotions and cognition are closely connected. Political scientist George Marcus draws upon recent work in neuroscience to show the role of emotion in reasoning. He has argued that emotions are critical to democratic life, and so, in his view, “sentimental citizens” are the only ones capable of making reasoned political judgments and putting them into action. Political theorist Sharon Krause also shows that emotions can enhance, not detract from, democratic deliberation. She begins her critique of the distinction between passions and reason with words that echo the findings of this study: “Our minds are changed when our hearts are engaged.”

Emotions play a particularly important role in cognitive processes regarding racial justice precisely because the minds of white Americans need to be changed. Whites need to break from the dominant color-blind ideology and adopt a racial justice framework. That seems to happen in crystallized moments when a direct experience of racism brings powerful emotions into play. These experiences shock whites out of a complacent belief in the fairness of American society and sear a new racial justice awareness into their consciousness.

In sum, many scholars of race relations and many policymakers have sought to make rational arguments that will convince whites that they have more to gain than lose by working together with people of color. Yet this study suggests that such an approach, however important, is ultimately too narrow. Rather, whites come to find common cause with people of color when their core values are engaged, when they build relationships that lead to caring and a sense of common identity, and when they can embed an understanding of their interests in a vision of a future, racially just society that would benefit all—that is, when the head, heart, and hand are all engaged. . . .

Moral, Visionary Leadership

I turn now to some of the broader lessons of this study for moving white Americans from passivity to action for racial justice. . . .

One of the key implications of this study is the need to bring values to the fore and assert moral leadership in the struggle for racial justice. There are two ways of thinking about morality in this regard, however, captured in my distinction between the moral impulse and a moral vision. Whites can be exhorted to do the right thing, or they can be offered a chance to join in an effort to pursue the moral project of a better society for all with justice at its core. To some extent, as we have seen, probably both appeals are necessary. Nevertheless, an appeal to conscience alone is insufficient. If whites feel only moral impulse, the result may be moralism rather than moral leadership. Perhaps that is the case for many well-meaning white people today. They believe racism is wrong, but they have not gone through the relationship-building and practice-based experiences that engage them in efforts to create and pursue values for a better society.

From this moralist point of view alone, the problem of racism is lodged in “bad” white people. Other whites are the problem, and moralists can easily denounce them. Even if they understand how racism functions in the institutional structure of American society, this still has nothing to do with them. Moralists have yet to discover two important and related lessons. First, as one activist in this study, Z. Holler, said, quoting Pogo, “The enemy is us.” In other words, all white people have been affected by racial indoctrination. Rather than dichotomizing the world into good and bad and simply blaming others, all white Americans have to take a close look at their own beliefs and behaviors.

Second, the perpetuation of racism is a complex problem. Whites need a serious, sustained effort to create institutional change and to deal with difficult challenges as they arise. Denouncing racism can make some whites feel good. Laboring in the trenches of the educational and criminal justice systems for sustained racial justice change, for example, is not all feel-good work even if it results in a rewarding life. The IAF organizers in this study, Perry Perkins and Christine Stephens, balked at my labeling them as activists because, in IAF thinking, activism represents short-term, unfocused action. I do not think the label “activism” necessarily means inconsistency or lack of commitment, but I do think their concerns help us appreciate that making serious advances in racial justice requires long-term engagement in public work to build power and new kinds of relationships that lead to real and positive change.

Part of this serious work involves creating respectful, collaborative relationships with people of color. The moralists, the do-gooders working for people of color rather than with them, may continue to keep that separation. People of color are perhaps rightly suspicious of the white heroes who think they can solve problems for them. Rather, moral leadership involves building reciprocal relationships in common pursuit of justice goals. . . .

Moralism in relationship to other whites presents a constant challenge even for the most seasoned racial justice activists. They struggle with honest confrontation with the racial beliefs and behaviors of other whites in a way that does not create defensiveness. They foster a sense of responsibility on the part of whites for action against racism. Responsibility is one thing, however; shaming and guilt trips are another. We have not seen much evidence in this study that shaming individual whites motivates a great deal of action. Indeed, the moral impulse arises not from shaming an individual as a bad person but from engaging positive values that people believe in and care about. Moral leadership lies in offering a moral vision, something to work for, a chance to become part of the racial justice family, as activist Christine Clark put it.

This study lends little support to the idea that confronting whites with their racial privilege constitutes an effective strategy to move them to action. Racial privilege may be a complex reality that white people need to grasp. Indeed, much important work to move whites toward racial justice understanding and action occurs under this banner. However, stressing privilege as a strategy to engage whites seems to emphasize the wrong thing. It focuses on the narrow and short-term benefit whites receive from a racial hierarchy rather than their larger interest in a racially just future. Alone, it seems to engage shame and guilt rather than anger at injustice and hope for a better future. It is moralistic rather than visionary.

Moralism ignores interests in favor of altruism. By contrast, moral leadership takes interests seriously but reshapes white people’s understanding of their interests and asks them to join a larger project that promises to create a better society for all. There is a material agenda here, one that offers better economic conditions and better social provision for people of color, as well as white families. However, this interest-based agenda is set and framed within a larger moral vision and political project.

There is evidence that suggests that this kind of moral leadership can be effective. Indeed, we are witnessing the rise of values-based activism in a variety of fields. For some, those values come from a religious faith that calls them to care for community and to act for social justice. Faith-based community organizing, for example, has emerged as a powerful force for engaging people in political action in their local communities. Indeed, several activists in this study are faith-based organizers and leaders. This kind of organizing engages value traditions while working for concrete, material improvements in the quality of people’s lives in housing, jobs, and education.

These values can also have secular roots like those based in the American democratic traditions of fairness, freedom, and justice. They can also be newer creations. Many activists in the environmental movement, for example, work not just to prevent ecological devastation but also to establish a new kind of society based upon the principles of working in balance and harmony with the world and caring about all forms of life. Environmentalists today try to live those values out in their relationships to each other and to the environment. In practice, both old and new values can be blended, as can religious and secular ones. More and more we are realizing that people care deeply about their values and can be engaged around them in progressive politics and other activist endeavors.

In the end, moral leadership is about creating a vision that engages values to shape people’s understanding of how their interests relate to racial justice. . . .

Building Multiracial Community

Another clear lesson of this study is the need to increase multiracial contact and collaboration in the United States. The activists in this study came to understand and care about racism through the people of color they knew personally. Certainly whites can teach other whites about racism. Indeed, the white activists in this study take that responsibility seriously. However, hearing stories directly from people of color engages the heart, as well as the head, and proves powerful. Through such relationships whites begin to care—and not just to know—about racism, and they begin to develop a sense of common identity and shared fate. Relationships, it appears, create the microfoundation for the broader visionary project of racial justice.

Studies of social capital, that is, social connections and ties between people, highlight the importance of these findings. Scholars of social capital like Robert Putnam have suggested that creating “bridging” ties across lines like race can create trust and cooperation and strengthen a sense of the common good. Yet we have far more “bonding” social capital, that is, ties among people who are like each other, than ties that bridge our differences. Nevertheless, despite persistent segregation, young people increasingly express a desire to be in a diverse setting. College may in fact be a particularly important place for whites to begin to create bridging ties.

Recent research by Robert Putnam highlights the importance of building these cross-racial ties. In studying racial diversity in localities across the United States, Putnam finds that areas with higher levels of racial diversity are lower in social trust. In other words, people appear to trust each other less when diversity is high. Whites trust blacks less and vice versa. Perhaps more surprisingly, however, people also trust other members of their own racial group less when diversity is high. In other words, diversity absent cross-racial relationships works against a sense of shared fate in the entire community. In this context, Putnam calls for investing in places where meaningful interactions across racial and ethnic lines occur, where people work, learn, and live together.

As Putnam and others realize, however, contact across race in and of itself may not move whites toward racial justice. Years ago, Gordon All-port put forward the “contact thesis,” which argued that contact with black people lessens prejudice in whites but does so only under certain conditions. Contact reduces prejudice in situations where whites and blacks hold relatively equal status, share common goals, and cooperate with each other in some way and where social norms support the contact.

The findings of this study echo these themes. However, even more, they help us understand the processes that occur within these relationships to enhance support for racial justice. In other words, they open up the black box of bridging social capital to reveal what happens inside, which helps us understand how certain kinds of contact change minds.

Still, our interest goes beyond mere contact and the lessening of prejudice. We are concerned with the role of relationships in developing an understanding of racism and a commitment to racial justice. I find that many pressures work against racial equality within multiracial settings. Indeed, whites build relationships with people of color “under the weight of history,” that is, in a context laden with unequal power relationships. Whites can unconsciously bring some of the prejudices they have learned from the larger society into multiracial settings, which leads people of color to mistrust their motives or commitments. In this context, positive action needs to be taken to construct institutional arrangements and policies that will promote truly collaborative relationships. . . . For example, explicit efforts to address racialized thinking or behavior prove important to lessening prejudice and moving whites toward racial justice. Moreover, I find that the more power that people of color hold in the situation, the more compelling the change in whites can be. More broadly, white activists emphasize the need for conversation based upon respect and honesty within these multiracial venues, as well as a genuine effort on their part to learn about the experience of people of color. To the extent that people can share stories across lines of race, mutuality and a sense of common cause develops.

We are also interested in more than creating one-on-one relationships across lines of race. Although those individual connections serve as a foundation for building collectivities, it is through creating community that whites can form shared identities with people of color and other justice-oriented whites. These groups, networks, and communities become the crucible where white activists develop a vision for a future multiracial society and work to implement it today. In other words, we are interested in fostering deeply democratic practices within multiracial institutions and communities.

![]()

a Warren, Mark R. “Winning Hearts and Minds.” From Fire in the Heart: How White Activists Embrace Racial Justice by Warren (2010) pp. 211–233. By permission of Oxford University Press, USA. Notes included in the original have been removed from this reprinted excerpt.