Balancing Act

winterstorm shrapnel

speckles the sky. My breath

roars in the silence

I’m half an hour from Tofino, in Maltby Slough, where my floathouse is now anchored. And I’m standing on the dock, staring at snowflakes falling fast, as if weighted. They are large as silver dollars, burying my small floating empire and veiling the wilderness beyond it. My open boat is moored to the floathouse and filling with snow. I search for the best tool with which to remove it, finally fixing on a dustpan. I’m used to bailing, but shovelling is another matter. With this blizzard I am completely cut off.

I wasn’t born a floathouse dweller. In fact, not until I arrived in Tofino did the word floathouse enter my vocabulary. Trinidad had been too exposed to the Atlantic, without the protected waters that make calm anchorage possible. In England, the closest equivalent was a narrow boat, a beautiful gypsy boat, horse-drawn along canalways and ornamented with bright scrolls of paintwork.

My partner and I first moved onto a floathouse at the end of a cold and particularly miserable winter, after I’d been in Tofino for about two years. It had been a trying time—a grand toppling of dominoes, situation by situation, down a precarious line. It began much earlier with the unplanned arrival of a large white dog tied to a pickup truck in our parking lot, her owner swept by a situational crisis. First, Carl and I looked after her for a week, then a month. After three months of smuggling “Sweetheart” into our no-pets apartment, and beguiled by the many charms her original owner named her for, our decision making ceased including prudence and included only sentiment: we wanted to keep her, name and all.

The snow is still falling. Where before it fell straight down, now it arrives in flourishes, skirling in the gathering wind. Beyond the opaque cloud of it, alder branches crack under the sudden weight and fall into the water, splashing loudly. A sibilant swishing noise begins to grow as snowflakes build on the water, layer upon layer, swirling in the tide. I bail the boat of snow for the second time, wondering how long the storm might last. For now, the island behind the floathouse is sheltering me from the southeast wind. As the storm picks up, however, no obstacle will stop the strongest gusts from finding their way in here.

We became aware that Sweetheart had reached adolescence when Sparky—the gentle giant of Tofino’s canine world—arrived on the lawn below our second-floor balcony and began a serenade that would have humbled Romeo. Besotted, he settled in for the duration of Sweetheart’s fertility, greeting us whenever we left the building and escorting us wherever we wanted to go. Sparky stayed despite the many midnight pleas for quiet by sleep-deprived residents. He stayed (albeit switching to sotto voce), despite the sudden throwing of shoes and other objects that accompanied those cries. And he stayed until no amount of dog smuggling could conceal our misdemeanour and we were asked to leave. But it was summertime and Carl suggested moving out to Echachis Island, his family’s traditional territory. The idea beckoned with a promise of outer-coast beauty. All we would need was a roof to keep the rain off. We’d build a cabin, no problem. There was now no question of parting from the dog, so instead we parted—blithely—with the only stable housing Tofino had to offer: adios Sin City, we’re moving to paradise! Of course, anything beyond summer living at Echachis was impossible given the rudimentary set-up of our hastily built shack. And so when summer ended, we joined the infamous Tofino Shuffle and searched for pregnant-dog-friendly housing—the sum total of which was Tom Curley’s generous offer of his boat, the Alannah C.

The storm is progressing and my friend’s words ring in my ears—casual words, words not reserved for teaching but for storytelling, words that could impart wisdom, if only I knew what to do with them. His words tell of blizzards sinking floathouses up north, camp workers using snow rakes to lighten the load on floathouse rooftops. Snow is a rarity in Clayoquot Sound. And without this storm, his story would seem irrelevant. But now, I’m looking at my roof. And one by one, the words are sinking in…

It was two in the morning at Fourth Street Dock, and the Alannah C was rocking violently in a southeast storm when Sweetheart leapt into the front berth and began the kind of panting that could only mean one thing. I soothed her until daylight, then moved her to the covered back deck where I’d set up a tarp-lined puppy corral, replete with privacy curtains, straw and a large, comfy bed. And so the pups arrived, one every half hour, seven silent balls of whiteness—silent, that is, until a few weeks later, when the joys of parenthood began to pale against the sounds of their nocturnal yips. So when we were offered the opportunity to house-sit for a friend—who not only had a garden, but also a safe garden shed, perfect for the ever-more-voluble and Houdini-like pups—we moved with alacrity. That the opportunity was a gift is impossible to deny. I probably owe it my sanity. But after a summer on Echachis, the winter routine of indoor life—with laundry, refrigerator, comfy beds and television—began to produce a strange effect on me. Maybe it was the reality of my new life, so far from home and family, immersed in the new-to-me culture of my partner. Maybe it was just the mundane nature of life on a street. Whatever it was, something was missing. And I didn’t know what it was.

One by one the puppies left home to live with their respective families. I didn’t have time to mourn them because our host returned and we had to move. We moved to a little house built snugly on a fibreglass barge at the end of a crab fisherman’s dock near Strawberry Island. The floathouse belonged to Mike, a bearded ex-American with a voice like a didgeridoo and a talent for the washtub bass. Mike preferred to winter in town and allowed us to occupy his vacant space. On the first night, I was sitting outside watching the swirl of the tide when a pod of orcas came by. In the dark, I counted five of them by the sounds of their blows alone. And just like that, as if they breathed new life into me, the feeling that something was missing slipped away.

I‘m standing on the dock, looking at my Christmas-cake roof and its foot-thick layer of snow. In my mind’s eye, marzipan figurines—red scarves flying—sled past the chimney, over the eaves and out into the storm. The wind shrieks and pounces on the figures, gobbling them up. More snow falls and the layer of roof icing grows thicker. I stop looking at the roof and begin to look at the waterline of my house, where the sub-floor fascia board is now several inches underwater.

Summer came and we moved again, this time to the cabin on Stone Island, directly across from Tofino. And it was there, for the first time, I decided to take matters of accommodation into my own hands with the help of a financial windfall I’d received. I contracted a builder to make a floathouse. I didn’t know where we were going to put it, but I knew one thing: I was tired of living in other people’s homes, on other people’s terms. And I wanted to live on the water. Carl and I had been beachcombing each winter and had amassed a floating herd of logs. They followed us obediently as we towed them to their fate at the Vargas Island sawmill. In exchange for half the wood, Neil Buckle milled them into beams and boards so that, piece by piece, the house became a reality.

The process was not problem-free, however, and the plan changed as I let myself be persuaded against a low-profile, single-storey structure, to a higher-profile peaked roof with an upstairs loft. But while I was envisioning a compact building with a small loft, the builder (a large man given to sturdy construction) had chosen eight-foot ceilings upstairs and down. The resulting post-and-beam house frame was beautiful. It was also too heavy for the float it was built on. Worse, on two sides it was built to the very edge of the float, making the house tippy and susceptible to wind gusts. As the float sank into the water, work slowed until no further weight could be added. When I ended the contract and towed the house home to Stone Island, it had a beautiful shake roof, a loft floor, a staircase and little else. It also had an unresolvable problem: insufficient floatation. The flat-bottomed float didn’t allow barrels of air to be added to it; they would roll out. There was no local technology that would allow for the addition of foam and there was not yet an Internet with which to search out new ideas. The beams were in the water, where they would be destroyed by shipworms. And I was out of funds and out of luck. For over a year, the house wallowed at anchor, regarding me through the baleful eyes of its empty window frames. I wallowed, too, the house my dismal anchor.

The water numbs my already stiff fingers as I check each corner of the house and monitor the slow descent of the beams in the water. I fumble with the tape measure, throwing it aside and grabbing a piece of kindling instead. I don’t need specifics, I need an overview: low risk, medium risk, high…The kitchen corner is lowest—one of the floatation tanks has some kind of slow leak. At this moment it is an inch lower than the rest of the house, more than a hand’s width down.

It was Rod Palm—shipwreck diver and local legend—who uncovered a trove of floatation tanks that were not cylindrical, but square. What’s more, they were free, save the cost of shipping and the diver to fill them with air. Rod installed them one bright fall day, my spirits rising with every inch of freeboard on the house. For the first time in months, I dared to think about building. I pictured siding and windows. I pictured our bed in the loft. Infused with hope, I could barely sleep and—childlike—I ran to the window in the morning to see how the house was doing. I gasped. The previous night everything had been perfectly level. Now, the house was listing heavily; the apex of the roof was off-centre, pointing to ten o’clock. One push and it would heel over. I sprinted down the long ramp, leaped in my boat and sped to the Norvan—the original wooden North Vancouver ferry, dry-docked on the shoreline of Strawberry Island—home to the Palm family. I idled my boat below their open kitchen window while Rod unravelled my panicked words, puffing on his pipe and squinting across the harbour at the floathouse. That morning he explained how saturated wood becomes lighter over time as it dries out. He readjusted the floatation, measuring each corner of the house. Once again, he left it perfect. Once again, by nightfall the house was listing, this time the other way. That night, I listened for every wave and breath of wind, willing the house to survive until morning. Rod fixed the floatation again and this time it stayed level. But now I saw the terrible irony: with buoyancy, the house was less stable than ever. And if just one of the floatation tanks gave out in the middle of a storm…

The storm is picking up, slamming the house with gusts. I shudder as the house heels over, holding my breath until the gust subsides and the house swings upright again. The added weight on the roof has changed the centre of gravity. The moment of return becomes longer and more painful to endure as the power of righting is diminished. The gusts push the house and the lines stretch tight in sudden jerks, as if the feet of the house are being pulled out from underneath it. I reel backwards, or sideways, flinging my arms outward. I imagine mounting the rickety ladder and climbing onto my steep roof. There is no way I can do it. The snow will have to stay there.

When swallows build a nest, if the consistency of the mud is too granular or too dry, the nest falls off the wall and crumbles on the ground. The swallows rebuild quickly, before it’s too late to produce a second clutch. Seasonal urgency triggers persistence and innovation. Eventually, the swallows will get the recipe right, create a sturdy nest and produce one or more broods of chicks. It wasn’t a brood of chicks I had in mind when I finished the house, it was the season: the coming of rain, the relentless southeasterly blowing through the skeletal framework, rinsing the wood of life and colour.

We were first-time nesters with no knowledge of house building. But we had to do something, so I suggested I hire a carpenter. We would be the carpenter’s helpers, working and learning, with access to tools that we otherwise wouldn’t have. The role of employer was a serious one and I approached it with gravity, seeking out carpenters and learning what they expected to get paid. I promised good wages, showed candidates the project, spoke of timelines and materials. People gave advice, showed interest, made suggestions. But in the way of small towns in winter, my options began to dwindle. The first candidate disappeared to Hawaii, the next to Mexico. A third candidate showed up a few times, never when expected. And the fourth candidate? There wasn’t a fourth candidate. As the situation unfolded, I gazed at raw materials, seeing them only as problems to be overcome. But one problem didn’t lie within the framework of the floathouse. That problem involved a different type of foundation.

As if an inner door had closed, my partner stopped speaking about the house. He passed no opinions, offered no explanation. He faded from the discussion like a forest creature, hidden by perfect stillness. Perhaps my ambitions for the floathouse were too high. Or the problems seemed insurmountable. For some reason I didn’t ask and for some reason he didn’t tell me. Whatever the issue, the consistency of our relationship was becoming granular. I sensed the onset of a gentle crumbling. We ate together, laughed together, visited our friends together. But in matters pertaining to the floathouse, and in matters I could sense, but not see, I was now alone.

I’m outside on the garden dock when the sky shivers, parting the curtain of snow to let the wind through. The house recoils as if slapped and I hear another noise, a slow creaking that gathers in intensity. When I realize what it is, I scramble backwards, tripping over plant pots and rainwater butts, reaching safety just as a foot of snow whooshes from a section of the roof. The floathouse bobs upward with sudden one-sided buoyancy. The other side of the house, the kitchen side, sinks lower. In an all-too-familiar sight, the apex of the roof points to ten o’clock.

In memory, the simple act of building was the most trying experience of my life. The work was complicated by features unique to the floathouse. The two longer sides of the house were bordered by water—no deck or dock; no place, other than a boat, on which to stand or prop a ladder; no way to retrieve the tools that inevitably dropped into the water; and of course, no electricity. I tied long lines to my thirteen-foot Boston Whaler, set a stepladder on the boat’s twelve-inch-wide wooden bench and climbed three precarious steps, siding in hand. One at a time, I nailed the boards to the side of the house. But inevitably, as I pushed against the house, the tie-up lines stretched and the boat countered my action by drifting away, stranding me at full reach over the water, arms trembling under the weight of wood, stepladder wobbling beneath me on the boat’s bench. In this position I’d have to reach for my hammer. And a nail. If I could get the first nail in, the rest would go easier. That first nail, however, was the toughest adversary, my house of cards tumbling at the slightest provocation.

Most annoying were the passing boats. A boat wake was all it took to knock the stepladder, and me, from the bench. If a boat went by, I’d let go of the board I was holding, climb down from the steps and wait for the wake to roll through. When calm was restored I’d replace the steps and mount them once more. Two or three boats in a row were enough to reduce me to tears.

As if the glissade of snow has uncovered a cache of words, the details of my friend’s warning suddenly spring back to me: Floathouses up north, sinking in the snow, becoming lopsided, flipping over. “Flipping over.” He said that. I close my eyes, unable to look. Then I run through the house from one side to the other. I have to move the boat away from the eaves. A fall of snow like the last will sink it where it’s tied. And whatever else happens, I need my boat.

Piece by piece, the floathouse neared completion. I bought foam insulation and pine panelling, the lightest weight possible. I rescued old windows, sanded and repainted them. My friend Ike installed them, adding pretty trim. In a complex operation, real carpenters showed up for work (when they said they would) and installed custom windows in the loft—double paned and storm strong, each one as tall as me. My work as a kayak guide took the majority of my hours, but the floathouse claimed the rest. Every evening for weeks, I wielded a six-inch belt sander, smoothing rough-cut cedar dock planks until they blushed soft pink. My right shoulder seized, requiring physiotherapy to fix, but I was so hyped I barely cared. I sealed the cracks between each board and then added coat after coat of varnish, making a floor of the utmost beauty. Domesticity left me. The longer the daylight hours, the longer I worked. That summer I remember a single day off. Unable to function, or even look at the floathouse, I drove to Echachis, unfurled a sleeping bag and slept in the sun on the beach, not stirring until evening shadows laid cool hands on my face.

Despite my exhaustion, I began to feel strong. Inner strength, which had ebbed as I neglected my own life in support of my partner’s, now crept into spaces that had recently grown hollow.

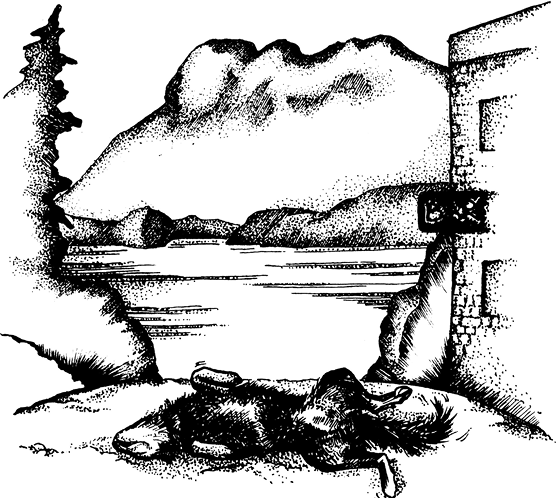

It’s three in the morning and I’m fumbling with the lines of the boat, my fingers swollen and numb. I guide the boat away from the avalanche zone of the roof. I dig into the snow, retrieve an oar, and paddle to the safety of the garden dock, where I stare at the tip-tilted house, wishing for an outrigger, anything to add stability. Then I kneel in the boat and begin to bail, an act of obeisance to appease the storm gods. The blue dustpan flashes back and forth in the beam of my headlamp. I move from bow to stern, grimacing as snow water seeps through the gap between rain pants and boots. Water seeps into my sleeves, too. As I scoop the last snow from the boat, water pools in the dustpan. Tired and cold, I slump on the seat. On the dock, dimples form in the snow, growing into puddles and ponds. Water soaks my hair, dripping into my eyes and trickling down my neck. The dustpan fills and a clear rivulet spills over the blue rim. I stare for long minutes before I register what I’ve been missing—water! The snow has changed to rain.

The floathouse was finished in 1997, except for one further measure that remained to be put in place. It had to move. Simple for a floathouse, complex for a quietly crumbling relationship. But Stone Island faced the storms and the floathouse was a target. Wave after wave, gust after gust, the house heeled over and back, its heavy framework creaking and twisting. One gust blew out the kitchen window—a single “bang!” and it vanished. I looked through the open hole and saw the frame of it floating by the rocks, far across the bay. A vortex followed, stealing papers and loose objects and whirling them out of the hole. As we nailed a board over the empty space, I knew I couldn’t put off leaving. It was a loaded decision, because I sensed I’d be leaving behind more than just an island. But anchorage was waiting in faraway Maltby Slough, a time-sensitive offer I couldn’t refuse. The move would be a leap of faith and one I might have to take on my own. I shook out my wings and wondered if they would lift me.

The rain is falling west-coast style: drenching, filling, flattening, eroding. A second weight of snow thumps from the roof and splashes into the sea, this time from the other side of the house. I grip the gunwales of the boat, relieved to have moved it in time. And as I stare at the water level of my house, my eyes blurred with rainwater, I see something miraculous—a way to add floatation to the sides. The water-level fascia boards hide a crawl space, which would allow for the insertion of beams—beams that could extend outward, allowing for a stabilizing, walk-around dock. It looks complicated, but I know it can be done. I laugh. Stability—achievable after all! The wind is lightening, shifting to the southwest when I stumble into the house, stripping off my soaked clothes. A joyous sense of possibility stretches me like the sky.